HORACE ASHENFELTER: PROFILE

b. 1923 5’10”/1.78m 128lbs/58kg

|

Horace Ashenfelter’s 1952 Olympic win in the 3,000 Steeplechase is widely regarded as one of the biggest upsets in Olympic track. To start with, he was not a steeplechaser. So he was competing as a novice in what is the most technical running event. His steeplechasing experience was limited to just six races (some say eight). Over the previous winter he had been practicing hurdling, but this was limited to working on a single hurdle that he built himself. Then he was up against two highly experienced and technically trained Russians, Vladimir Kazantsev and Mikhail Saltykov, the first two to break the 1944 world record of 8:59.6 with 8:49.8 and 8:57.6 respectively. Ashenfelter came to the Olympics with a best of 9:06.4, a full 17.8 seconds slower than Kazantsev’s new 1952 world record of 8:48.6.

So great was the Russian’s superiority that Ashenfelter’s team-mates took to teasing him the night before his heat: “Horace, how is it going to feel to be out there running on the track when Kazantsev is in taking a shower and on his way home?” Another team-mate said, “I’ll bet Horace will have only three laps to go when Kazantsev is getting his gold medal.” But according to Bob Richards, who recorded these comments in his autobiography, Ashenfelter’s confidence was undiminished: “I don’t care what you say. I believe I can go out there and win. I know that Kazantsev is great; I know he’s terrific. But I believe that somehow, if I give everything I’ve got, I can win.” (The Heart of a Champion)

A closer look at Ashenfelter’s early career, however, shows that there was considerable justification for his pre-race confidence. Indeed, there is a lot of evidence to suggest that Ashenfelter’s Olympic win in Helsinki was not such an upset at all.

Although Ashenfelter is best known for his great Olympic win, there were many other achievements in his long running career that stretched from 1946 to 1957. He began as a Penn State track star and then became one of the top American distance runners. With 18 national titles to his name, he was at his best in the indoor season, winning countless races over Two Miles, his favored distance. He also found success outdoors with two national cross-country titles (1955, 1956) and six track titles. Somewhat forgotten is his fine 8:51 in his Steeplechase heat in the 1956 Olympics. This was an excellent time for a 34-year-old who had qualified in only third place in the US trials with 9:02.4.

Ashenfelter was never a full-time runner. After graduating from university in 1949, he worked first as a salesman and then, helped by his friend Fred Wilt, joined the FBI. Later, after his retirement from track, he worked as a precious-metals salesman. Throughout his running career he worked full-time to support his family and had only one hour to train on week days. Apart from the 1952 Olympics, his running focus after university was the thriving indoor season. Generally, he raced a little over the country before the January start to the indoor meets, and he ran a few outdoor races in the early summer after completing the indoor calendar.

------------

|

|

College days: Ashenfelter (255) after running second in the 1947 IC4A cross-country race. |

Born and raised in the American state of Pennsylvania, Ashenfelter was an all-round athlete in high school. He played as a 145-pound guard and tackle in football; in baseball he batted .400 and pitched. As well, he was on the school track team (best Mile 5:00) and the baseball team. “In basketball I was a toughie,” he told Gary Cohen. “I hit the boards pretty hard and could rebound. I wasn’t very fast or talented, but I worked hard. (Interview with Horace Ashenfelter, 2010, garycohenrunning.com)

At Penn State University in his freshman year (1942-3) he showed most interest in boxing. His university career was soon interrupted by World War 2. He served for three years in the Air Force as a fighter pilot, achieving the rank of Lieutenant. While training as a cadet, he did a lot of general physical training.

On completion of his military duties, he returned to Penn State. There he met runner Curt Stone, who encouraged him to try out for the Penn State University team. Under Coach Chick Werner, Ashenfelter steadily improved. From 1946 to 1949 his Two Miles time dropped from 9:54 to 9:03.9. He excelled on the track, on the boards and over the country. Among his achievements were two IC4A titles for Two Miles (1948, 9:13.2; 1949, 9:09.2), an IC4A Indoor Two Miles title (1948, 9:11), and an NCAA Two Miles title (1949, 9:03.9). Another highlight was a victory in the Penn Relays 4xMile, where he was joined on the team by his two brothers Bill and Don.

His university days saw a couple of setbacks too. In 1948 he went off course in the NCAA Cross-Country Championship race while leading by 30 yards. This cost him the race, although he did finish second. And he made an unsuccessful attempt to qualify for the 1948 Olympic team, finishing fifth in the 5,000 trial race. But this promising run earned him at least a place on a USA team for meets in Oslo and Helsinki. He placed third in a 1,500 with 3:57.0. He later said his failure to make the 1948 Olympic team was the greatest disappointment of his career. (T&FN, October, 1953)

Working Husband and Father

Despite his family obligations, Ashenfelter continued running seriously after he left Penn State. ‘I figured I had about an hour each day that I could run. I would get home at 6:00 and take my trot. I got my schedule lined up so that at the end of that hour I was tired. I had worked out hard. It was as intensive as I could do.” (wisecontradictions.com)

As NCAA and IC4A Two-Miles champ, he was already approaching the top of the American distance running scene, but there were two established runners who dominated him in national races: Fred Wilt and Curt Stone. Ashenfelter had already clashed with Stone in the Kinghts of Columbus Two Miles, losing by 15 yards after Stone sprinted past him at the end. It would take a while for Ashenfelter to beat these two fine runners.

|

|

1950 Atlantic CIty Boardwalk Mile. Ashenfelter (4:07.5) finishes second to Fred Wilt (4:05.5). |

He soon showed that he had developed stamina during his Penn State years. In December 1949 he finished third in the AAU cross-country championship: 1. Wilt 30:31; 2. Stone 30:45; 3. Ashenfelter 31:19. Indoors he raced 12 times over the 1950 season, but he never won. He always finished high in the field but was always behind Wilt, Stone or John Barry. He often ran at the front, but he lacked a kick, and was easy prey for the fast finishers. Nevertheless, he kept trying, and after pushing Stone to a close Two Miles race at Madison Square Gardens, he finally broke the 9:00 barrier in Boston: 1. Stone 8:55.5; 2. Wilt 8:57.0; 3. Ashenfelter 8:59.6. He could take a lot of credit for the fast times as he led in 2:13, 4:27 and 6:44.

Outdoors, he won his first Senior title by taking the AAU 10,000. With a time of 32:44.2, he won by three-quarters of a lap. Then in August he traveled to Europe with a USA team, winning his first two races (9:15.6 for Two Miles and 14:13 for Three Miles).

1951 Indoor Season

Ashenfelter, now working for the FBI through his contact with Fred Wilt, started winning on the boards. He won four of his five Two Miles, though he didn’t break 9:00. In the AAU Three Miles he pushed Stone to a close race, finishing only five feet behind the 14:12.8 winner. Outdoors he ran the 3,000 Steeplechase in the AAUs and won in 9:24.5, beating Curt Stone, who had run the 10,000 the previous evening, into second place. This may well have been his first serious Steeplechase ever. His time is not listed in the 1951 World Rankings; he should have been placed 46th.

Ashenfelter has said that he started steeplechasing in order to get team points for his NYAC club. He has also been quoted as saying that he chose the Steeplechase because it was “my best chance to win an event in the Olympics.” (New York Times, July 25, 1952) His inability to beat Wilt and Stone in flat races may also have suggested the Steeplechase in the upcoming Olympics. Ashenfelter did start practicing over hurdles that winter.

Pre-Olympic Races

Ashenfelter had two major runs in the fall of 1951, a first-place tie in the Metropolitan AAU CrossCountry with fellow FBI agent Fred Wilt, and a third-place finish in the AAU Senior race behind his brother Bill and Fred Wilt. Then he made quite an impact on the indoor scene. After losing his first race to Wilt, Ashenfelter won four consecutive Two Miles in January: 9:05.0, 9:14.9, 9:06.2 and 9:07.4. Stone then ran a fast 9:00.6 to beat Ashenfelter, only to lose to him a week later. This set up a big clash in the AAU Three Miles, which Ashenfelter won in a fast 14:02.0. Clearly he was rounding into form, and a week later was able to run a Two Miles PB of 8:51.4 behind Wilt (8:50.7, an American record). Ashenfelter then beat Stone in a close race with another fast Two Miles time of 8:54.4.

After such a successful indoor season, his prospects for his outdoor season and an Olympic berth looked better than ever. He ran a Two Miles Steeplechase in 10:22.4 three weeks before the Olympic trials and won by 75 yards from his brother Bill and Stone. In the trials he qualified in two events. First he finished third behind Stone and Wilt in the 10,000 (30:45.8). And the next day, tired from the 10,000, he finished second behind McMullen in the 3,000 Steeplechase, with Bill Ashenfelter also qualifying in third. And then in the final tryouts, a fresh Horace Ashenfelter ran his fastest Steeplechase, finishing just ahead of his brother Bill 9:06.4 to 9:07.1. Ashenfelter’s time was a new American record, beating Harold Manning’s 1938 time of 9:08.2. This race was a clearly Ashenfelter’s attempt to help his brother to a fast time and Olympic qualification, although Track & Field News wrote that he “appeared close to all-out.(August, 1952) Ashenfelter’s 9:06.4 would have ranked him fifth in the world a year earlier in 1951, but the world leader, Vladimir Kazantsev of the USSR was considerably faster with 8:49.8.

For his final preparation for the Olympics, Ashenfelter did get some help from his employer, the FBI. He was relocated to their Princeton office so that he could do workouts on the track there. “This was normally a no-no,” Ashenfelter told Gary Cohen. “I did do my FBI work, though I had more time to train and was able to train twice a day on some days.” (garycohenrunning.com)

The Steeplechase became an Olympic event for the 1900 games. For three games the distance was 2,500. The event was not included in the 1912 games, but it reappeared in 1920 to become a regular event over 3,000m. Although James Lightbody won the Steeplechase gold for the USA in 1904, as Roberto Quercetani has written, “the steeplechase never really caught on in the States.” (A World History of Track and Field, p. 180) Indeed, the state of steeplechasing in the US was poor when Ashenfelter was developing as an athlete; Bob Macmillan, the best American steeplechaser in the 1948 Olympics fell into the water jump three times, apparently “going out of sight the last time.” (Track & Field News, August 1948) When the Steeplechase was run in the US, it was usually over two miles. In fact, some of Ashenfelter’s few steeplechases were run over this two-mile distance. Even in the early 1950s the event had not become standardized worldwide; the IAAF finally set standards for the event in 1953 and for the first time recognized world records for the event.

Helsinki 1952

When Ashenfelter came to Helsinki in the summer of 1952, he was ranked 16th in the world for his 9:06.4. No Americans had appeared in the world Steeplechase rankings since the 1948 Olympics; the event was really a European specialty. The previous year had seen a big breakthrough as the 8:59.6 world record was broken by two Russians, Kazantsev and Saltykov. Kazantsev had improved the as-yet-unofficial world record by a huge 9.8 seconds to 8:49.8. Furthermore, he had improved it even more just before the Helsinki games to 8:48.6. No one had ever run within nine seconds of this new record, so it was no wonder that Kazantsev was the odds-on favorite.

|

|

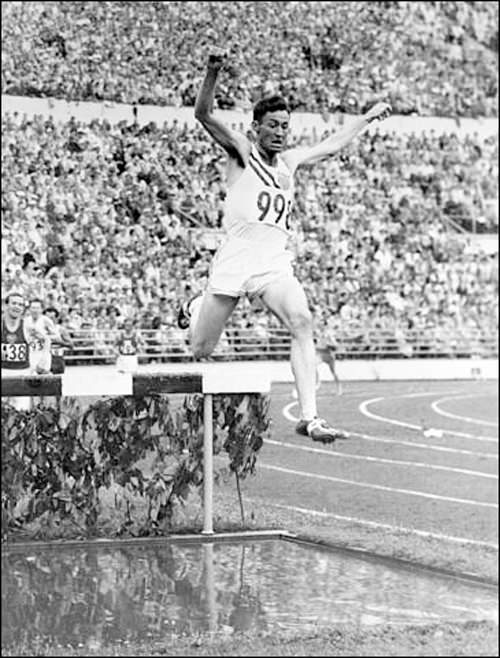

In a commanding lead in his Olympic heat. |

Before his heat, Ashenfelter received the blessing of the American authorities to withdraw from the 10,000 so that he could concentrate on the Steeplechase. He watched Curtis Stone and Fred Wilt run poorly to finish 20th and 21st in the 10,000; and he watched Wes Santee, Stone and Charlie Cappozoli get eliminated in the 5,000 heats. And then in earlier heats of the Steeplechase, his brother Bill dropped out and Browning Ross finished last. The reputation of American distance running now depended on him alone.

He took lead early in his heat and ran without hearing lap times. His first K was a fast 2:50.4--8:31 pace. Then he eased off a little with a 2:58.6K. He kept going strongly and finished 4.8 seconds in front of the Russian #2 Saltykov with the incredible time of 8:51.0. This was the third fastest time ever and a full seven seconds faster than Kazantsev’s time in his heat. He had run 15.4 seconds faster than his previous best and 12 seconds faster than he need to qualify, but he had also sent a strong message to the Russians. All of a sudden he was one of the favorites for the final two days later.

Olympic Final

|

|

Neck and neck in the later stages. Kazantsev always on the outside. |

The edited film of the final shows Ashenfelter setting off easily in last place, while his tense opponents all dashed for a good position. Saltykov, the Russian number two, took the lead after a lap, clearly undertaking a supporting pacemaker role for his fellow Russian Kazantsev. The first two laps were 67.1 and 2:20.5. Ashenfelter, who had moved up to fourth after a lap, now moved ahead. He kept pushing the pace (2:49.8 for first K), and after four laps only Kazantsev could stay with him. The Russian kept close to Ashenfelter’s right shoulder and was still there at 2K (5:47.4). Kazantsev looked comfortable, despite almost falling at one hurdle. In fact, the two demonstrated very similar hurdling ability; Ashenfelter’s technique was not at all inferior to the Russian’s.

|

|

Ashenfelter and Kazantsev move away from the rest of the field. |

Coming into the last lap, Kazantsev was still on Ashenfelter’s shoulder. Down the back straight the Russian’s head began to nod. He made his move just before the last bend, but his form had become laboured, while Ashenfelter looked relaxed and capable of keeping close. Kazantsev took the last water jump just ahead. Ashenfelter, moving out a little in preparation for passing the Russian, landed much better that his opponent. While Kazantsev had to recover from a poor landing, Ashenfelter immediately began his drive for the tape, and after just nine strides he was ahead. Kazantsev was done and submitted right away. Ashenfelter was away, but he still had the last hurdle. It proved to be a problem as he stuttered his stride and almost came to a stop. But with his rear leg barely clearing the hurdle, he was over safely and reached the tape with a huge 6.2-second advantage. Not only had he won the gold medal but he had also decimated the unofficial world record. 1. Ashenfelter 8:45.4; 2. Kazantsev 8:51.6; 3. Disley 8:51.8.

Performance Analysis

What contributed to this amazing performance? First was Ashenfelter’s positive attitude. Even in the face of impossible odds, he believed in himself. Also, his morale was boosted by the presence of his former Penn State coach Chick Werner: “It helped me having a coach who was familiar with me.” (Interview, Gary Cohen) His thoughts on the last lap were another indication of his positive mindset: “My feet felt like dead weights…. I never felt like quitting so badly in my life, but I just had faith, a faith deep down in my heart, that if I could somehow keep picking them up and putting them down, I could win that race.” (Richards, The Heart of a Champion, pp. 43-4)

|

| Kazantsev hanging on to Ashenfelter. |

Second, Ashenfelter’s competitive and tactical skills had been honed by three indoor racing-seasons (at least 27 top-class races). In the confined space and the tight corners, he learned how to position himself, how to pass economically, and how to survive the body clashes and elbows. Thus Ashenfelter was not disturbed by the presence of Kazantsev close on his right shoulder for much of the latter stages of the race. In fact, he made use of the Russian’s attempt to pressure him: “I didn’t mind that…he was running on my shoulder…and adding three or four yards to each lap. I ran him a little bit wide on the corners, and we bumped several times as he was running that close to me. That didn’t bother me, but it may have bothered him—I don’t know.” (Garycohenrunning.com)

Third, Ashenfelter specialized in the Two Miles event. He trained himself for competitive efforts of approximately nine minutes—the same time needed to run a world-class Steeplechase. The Two Miles was a standard event in the US at this time, especially for indoor competition. Whereas runners outside the US focused on either 1,500/Mile or 5,000/Three Miles, Ashenfelter was tuned for a nine-minute effort. This in-between distance was not something most track runners were comfortable with.

|

|

Kazantsev almost falls after taking a hurdle on the penultimate lap. |

Fourth, Ashenfelter had taught himself how to hurdle and water jump. Much has been made of the technical proficiency of the Russian steeplechasers, but the two films of the Olympic race show that Ashenfelter was just as efficient as Kazantsev over the hurdles and water jump. He never lost any time over the hurdles. Only at the very last hurdle did he show any difficulty, and that was clearly the result of exhaustion. He was good at the water jumps too, despite his unusual practice of raising both arms above his head.

|

|

Kazantsev stumbles after the final water jump. Ashenfelter will pass him after nine more strides. |

And fifth, Ashenfelter was in the best shape of his life. He had raced intensely during January and February, but then he had eased off serious competition until June. In that month he had run three steeplechases, just enough to get him back into racing shape. So by the end of July he was peaking. His year had gone perfectly for the Olympics, and he had had no injury problems or other setbacks. Thus he could say, “I was in outstanding shape and had no bad luck occur.” (Garycohenrunning.com)

|

|

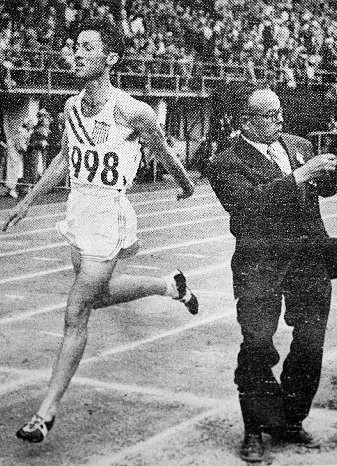

At the finish, Ashenfelter almost collides with an official. |

Belief in himself, competitive experience, distance specialization, hurdling efficiency and a perfect build-up—all these gave him distinct advantage over his competition. And this advantage was enhanced by the maturity that the 29-year-old brought to the race. Military service, a university degree and a family with two children all combined to enable him to cope with the stresses of his first Olympic Games. At 29 he was at the ideal age to combine maturity and physical ability. And the result was an Olympic gold medal and a world record.

Continuation

Many American runners would have retired at this point. He had achieved the ultimate in competition and was returning to family and FBI responsibilities. But Ashenfelter, now 30, continued. He dominated the indoor season for the first time, as his two arch-rivals, Wilt and Stone, were not in top form after their disappointing Olympic 10,000 runs. He won the Millrose Two Miles by almost a lap in 8:54.6 and then tackled Wilt’s indoor record of 8:50.7. He ran 8:53.0 and 8:53.5 in two consecutive meets. In his second attempt he went through the first mile in a fast 4:21.4, and need to run only 65 for the last 440. However, the fast early speed caught up with him and he could only manage a 67.8. The New York Times reported how this record attempt excited the crowd: “Not since the days of Gil Dodds have the Garden railbirds rallied so wholeheartedly to the support of a man with a mission. Practically everyone in the stands was as exhausted emotionally as Ashenfelter was physically at the end of the race.” (Feb. 7, 1953). Next he beat Olympic silver medalist Herbert Schade over Three Miles (13:47.5 to 14:02.2) and over Two Miles (8:57.6).

At this time he was awarded the prestigious James E Sullivan Trophy. It was given annually to the outstanding American athlete in all sports.

With his indoor season completed successfully—he was unbeaten over Two Miles—he used his fitness to win the outdoor AAU Two Mile Steeplechase by 150 yards in 10:02.5. Five days later his 8:45.4 world record was beaten by Finn Olavi Rintenpaa (8:44.4). Technically, Ashenfelter’s 8:45.4 was not recognized by the IAAF as the 3,000 Steeplechase was not recognized as an official event until after the 1952 Olympics. Nevertheless, his time is still included in all listings of world records.

Another Indoor Season

He was in good form again for the 1954 indoor season. Again he was unbeaten over Two Miles until his last race of the season. In February, he finally beat Fred Wilt’s Two Miles record with 8:50.5, but he failed to beat Greg Rice’s three Miles indoor record of 13:45.7, running 13:56.7 to take the AAU title for the third consecutive year. In his next race, the Knights of Columbus Two Miles, he had a chance to beat Fred Wilt, who had come out of retirement for the 1954 season. Wilt, who had beaten Ashenfelter in nine previous encounters over Two Miles, gave him a good race, but he was ten yards back when Ashenfelter breasted the tape in 8:58.5. A week later Wilt got his revenge, winning by a step in 9:01.4.

Outdoors at Compton, California, Wilt beat Ashenfelter again, this time with 8:58.8. Ashenfelter finished his brief outdoor season with the AAU Three Miles title (14:31.3). By this time it was clear that he was thinking about the 1956 Olympics. He came back for the 1955 indoor season in fine condition and won eight of his ten races. Only Fred Wilt and Gordon McKenzie were able to beat him. His best Two Miles time was 8:55.5 and he won the AAU indoor Three Miles title yet again.

In March he went to Mexico City for the Pan Am Games and in high altitude placed second in the 5,000. Then in June he broke the American Two Miles record at Compton with 8:49.6. Finally, again at altitude, he won the AAU Three Miles title once more in 14:45.2. All looked well for the following year’s Olympics, but he was clearly finding it increasingly hard to keep going. In January of 1956 the 33-year-old announced that he might not be able to compete in Melbourne: “I don’t think I will have the time to go to Australia. My family obligations and work schedule may make it impossible to try for the team.” (New York Times) Nevertheless he committed to staying in shape and said he would make a final decision in the spring.

Second Olympics

Ashenfelter thus entered his seventh indoor season with a different attitude. And for the first time he developed some nagging injury problems that twice forced him to drop out of races. But a lot of the magic was still there. In January he reeled off four consecutive Two Miles victories (9:03.6, 9:06.6, 9:14.2, 9:01.7). After dropping out with calf problems in the Millrose Games, he won another three (9:06.6, 9:04.5, 9:07.6). So it was a successful 1956 indoor season, albeit with slower times. And on May 31 he announced that he would after all be trying out for the Olympics. Three weeks later he won the AAU Steeplechase title with a 9:04.1, his third fastest time ever. A week later he qualified for Melbourne in the trials, placing third behind Phil Coleman (9:00.3) and Charlie Jones (9:00.6). His time was even faster than his AAU run: 9:02.4.

After a couple of warm-up Two Mile Steeplechases in September (9:49.0, 10:04.4), Ashenfelter arrived in Melbourne in excellent shape. And it was a fine achievement to run 8:51 in his heat, although that time earned him only sixth place. He had failed to qualify for the final by three seconds. “I guess I’m too old,” the 33-year-old told the press. “I’ve had it. That is as fast as I can run.” (New York Times, Nov. 28, 1956)

Well, he may have had it, but he still wasn’t finished. He came home from the Australian summer and proceeded to win the AAU cross-country title by 40 yards. And then in his first indoor race of 1957 he lapped the field to win a Three Miles in 14:13.9. Two weeks later he was beaten into third by Fred Dwyer (8:52.4), but he came back to win a Two Miles in Philadelphia (9:01.8). After two second-place finishes, he won the Millrose Games Two Miles in 9:02.3. A month later he won the Knights of Columbus Two Miles for the sixth consecutive time in 9:01.4. This was his last great race and wrapped up his eighth indoor season. His last recorded race was on June 8, when he won an outdoor Two Miles in 9:10.4.

---end

1 Comment