1960 Olympic Games

Rome, August 25-September 11

800

Roger Moens (30), a very experienced runner with a great competitive record, was the co-favorite with Paul Schmidt, who had been fastest over 800 in 1959 (1:46.2). George Kerr (22) of Jamaica, a talented newcomer, was also fancied. The demanding heats eliminated two other top picks, Brian Hewson of Great Britain and Stefan Lewandowski of Poland (second fastest over 800 in 1959).

|

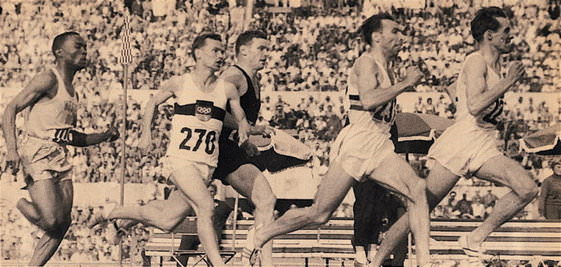

| Entering the final straight: Waegli leads Moens, Snell, Schmidt and Kerr. |

The 800 race almost always provides a close finish. This time five of the six finalists were in a position to win as they entered the final stretch. As expected Christian Waegli led the field through the first 600 in 25.4, 51.9 and 1:19.1. Schmidt of Germany and Kerr of Jamaica followed, with Snell of New Zealand and Moens of Belgium close behind. At 600 Moens pushed into second place behind Waegli. Behind Moens, Snell was on the inside, boxed in by Schmidt and Kerr.

Going into the straight, Moens looked in complete control as Waegli started to fade. He roared past the Swiss runner and seemed to have the race sewn up. Alas, he didn’t see Snell coming through on the inside; it was too late to react. Snell, who had thought the race was lost, found the strength to move through a gap that opened up between Waegli and Schmidt on the final stretch. He was ahead only with his last ten strides. Moens had run an almost perfect race, but had he presumed victory before the tape? Snell showed remarkable strength to run such a fast time—1:46.3, only 0.6 outside Moens’ WR—after three rounds in the previous two days.

|

| Moens sees Snell--too late. |

Snell’s victory was a huge upset. He had been sent to Rome merely to get Olympic experience. Moens was devastated by his loss; a film clip shows him kneeling on the grass after the race, weeping. Kerr was in a great position coming into the straight, but didn’t have the gas on the run-in. Schmidt must have been disappointed with fourth place.

1. Peter Snell NZL 1:46.3; 2. Roger Moens BEL 1:46.5; 3. George Kerr JAM 1:47.1; 4. Paul Schmidt GER 1:47.6; 5. Christian Waegli SWI 1:48.1; 6. Manfred Matuschewski GER 1:52.0.

1,500

This race had a clear favorite: Australian Herb Elliott. His stunning Mile and 1,500 WRs in 1958 had shocked the world. The only concern was his lack of top-class competition immediately before the Games. Still, there were some other good runners in the field. Dan Waern of Sweden and Rozsavolgyi of Hungary were the pick from Europe. And France had two fine finalists in Michel Bernard and Michel Jazy. Two other potential medalists, Merv Lincoln of Australia and Siegfried Valentin of East Germany, were eliminated in the heats.

Elliott’s well-known tactic was to go early, so the chances of a highly tactical race were low. But the early parts of the race needed a self-sacrificing pacemaker if it wasn’t to be a dawdle. Then it was just a question of whether anyone could hang on to Elliott and challenge him in the last 100.

|

| Elliott pushing the pace as he approaches the bell. Rozsavolgyi, Jazy (hidden), Vamos, Bernard, Burleson and Waern follow. |

Fortunately for Elliott a perfect pace-maker emerged in Michel Bernard, a 1,500/5,000 runner who went straight to the front and led the field through the first 800. His pace was perfect for a WR: 28.3, 58.2, 1:27.4, 1:57.8. Elliott, who had started comfortably, gradually moved though the field and was third at 800. Then he made his move—much earlier than expected. He upped the pace with a 13.2 100 meters (the race had averaged 14.7 until then). The field went with him. After running the bend and the straight to the bell almost as fast, he took off again, running the 100 meters of the curve in 14.0. His third lap had taken 56.0. This last 100 had finally broken up the field. At 1200 he was 3 meters up on Rozsavolgyi, 5 on Jazy, 8 on Vamos, and 13 on Bernard and Burleson.

With 300 to go, Elliott went even faster with a 13.2 100 meters. Behind him Jazy moved by Rozsavolgyi but was now 8 meters down on the Australian. Elliott maintained his fast speed with a 13.6 100 round the final bend. This gave him a 15-meter lead as he faced the wind in the last 100. Although Elliott slowed in the run in, his margin of victory increased even more. He finished in a new WR of 3:35.6, beating his own WR by 0.4. He had run the last 800 in 1:52.8. Behind him Jazy, running the race of his life, held off the closing Rozsavolgyi for the silver. The experienced Dan Waern came through from seventh to fourth in the last 300 to catch the surprising Zoltan Vamos (previous PB 3:40.5) in the last meters.

It was an instinctive performance by Elliott; he was too strong, too determined and too talented for his opponents. Roger Bannister, writing for Sports Illustrated, described Elliott’s race poetically: “It was Elliott, with the hawk nose, the gaunt Viking face; Elliott of the lean body and the smooth stride; Elliott, lithe and stealthy, about as gentle as a tiger. This was a man made for this form of self-expression, the rest of the field having somehow learned it painfully and inadequately. This was running, the instinctive and unfettered expression of every potentiality.” (Sept 19, 1960)

Jazy ran the race of his life and obliterated his PB. In his autobiography he wrote little about this great race, but the few words showed he was mentally prepared for the biggest race of his life: “I was wonderfully lucid. This time I didn’t let myself get boxed in. We were in one group. But I knew that sooner or later a break would scatter us to the four winds.” (122) Rozsavolgyi at 31 ran brilliantly for third. He was only a fraction of a second outside his 3:38.9 PB

1. Herb Elliott AUS 3:35.6 WR; 2. Michel Jazy FRA 3:38.4; 3. Istvan Rozsavolgyi HUN 3:39.2; 4. Dan Waern SWE 3:40.0; 5. Zoltan Vamos RUM 3:40.8; 6. Dyrol Burleson USA 3:40.9.

(Note: Thanks to Track & Field News for the useful 100 splits in this race.)

5,000

If Elliott’s victory in the 1,500 was the most dominant performance of the Games, Murray Halberg’s was the most courageous. To inject a 61.1 tenth lap in a 5,000 meant that he had exposed himself completely.

The heats eliminated some runners thought to have a medal chance: Gordon Pirie and Bruce Tulloh of Britain, Boris Yefimov of the USSR, and Miroslav Jurek of Czechoslovakia. On the other hand, Dave Power of Australia and Kiwi Halberg looked good in the heats. Also fancied were Poland’s Kazimierz Zimny and Germans Hans Grodotzki and Friedrich Janke.

The field of 12 for the final stayed together for seven laps. Zimny did most of the leading through 62, 2:08, 3:15, 4:20, 5:28, 6:38, 7:45 and 8:54. It was in the seventh lap that things started to happen. Grodotzki moved up from the back and Halberg shadowed him. But it was Dave Power who really stirred up the race as he roared into the lead at 8 1/2 laps. He soon eased up and was caught by the pack, which was now reduced to seven by the 66-second ninth lap.

|

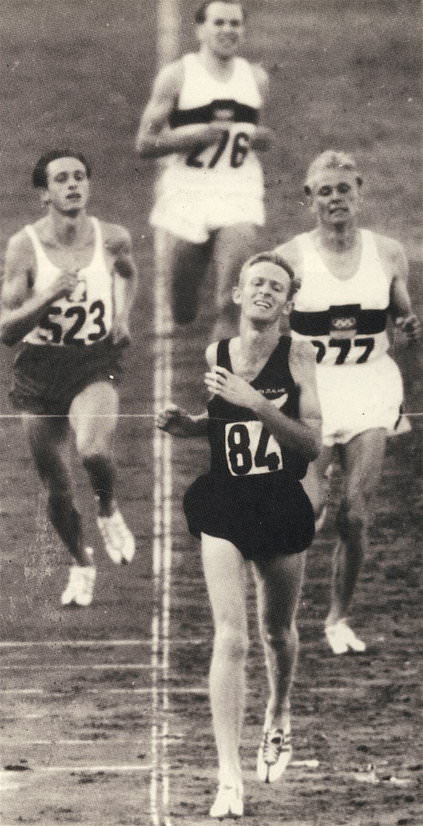

| Halberg holds off Grodotzki, Zimny and Janke. |

Just when the pack relaxed after catching Power, Halberg took the initiative and sprinted away. He wrote in his autobiography: “I improved my place to second in the field. I settled there momentarily, gathered my strength. Then with all I had, I sprinted.” (CleanPair of Heels, p.105) The crowd roared in appreciation as Halberg quickly opened up a 12-meter gap. By the end of the lap Halberg was 20 meters ahead; he had run the lap in 61. Grodotzki was the only one to react at all to this breakaway.

Halberg maintained his 20-meter lead on the next lap (64), while Grodotzki had moved 20 meters ahead of Janke in third. Halberg’s pace dropped to 34 in the next 200, leaving him 15 meters up on Grodotzki at the bell. Both the leading pair were hurting by now and the field was closing on them. With 200 to go, Halberg still had 12 meters on Grodotzki, while Janke and Zimny were closing fast.

There was some desperate hanging on in the final straight. Halberg held on for an 8-meter victory, while Grodotzki barely held off Zimny for second. Four of the top six ran PBs: Halberg, Grodotzki, Power and Maiyoro. Halberg’s time put him in fifth on the all-time list.

1. Murray Halberg NZL 13:43.4; 2. Hans Grodotzki GER 13:44.6; 3. Kazimierz Zimny POL 14:44.8; 4. Friedrich Janke GER 13:46.8; 5. Dave Power 13:51.8; 6. Nyandika Maiyoro KEN 13:52.8.

10,000

There was some controversy about this race before it started. Many considered the size of the field (44) was too large for one race. But the IAAF refused requests for heats. Fortunately only 32 runners lined up in two rows for the start.

There was a strong Russian presence in this race with Pyotr Bolotnikov (30), Aleksey Desyatchikov and Yevgeniy Zhukov. All three had posted times under 29:00. Hans Grodotzki of Germany, with a 28:57.8 PB, was also fancied. Australian Dave Power, who had won both the 6 Miles and the Marathon at the 1958 Commonwealth Games, was another good prospect. New Zealand’s Murray Halberg could not be discounted either; he had already won the 5,000 and had the best 10,000 PB.

The Russian trio took charge of the race from the start. They clearly had a plan to work as a team, a plan that was to create controversy afterwards. Power and Rhadi were also in the front at times. Bolotnikov made sure the pace was fast by leading for the first 2K (2:48, 5:37). Only the Moroccan Rhadi stayed with him. Bolotnikov maintained the pace through 3,000 (8:29) but then slowed to pass 4,000 in 11:24. This slowing allowed the pack to join him. The first three Ks had been fast—28:18 speed; Bolotnikov clearly thought that his best chance of winning was off a fast pace.

The 5,000 mark was reached in 14:22.2 (compare Kuts’s 14:07 in the 1956 Olympics). The splits were as follows: 2:48, 2:49, 2:52, 2:55, 2:58. There were still 20 in the lead group. It was now time for Bolotnikov’s team-mate Desyatchikov to lead and ensure the pace did not slow. The next two Ks in 2:56 and 2:53 reduced the field to 14: three Russians, three Brits (Merriman, Pirie and Hyman), Rhadi, Iharos Power, Grodotzki, Halberg, Krzyszkowiak, Anentia and Truex. Desyatchikov still led with Bolotnikov right on his heels.

Australian Dave Power made a big move with seven laps to go. Only five went with him: Bolotnikov Desyatchikov, Grodotzki, Merriman and Hyman. Soon the lead group was four as the two Brits fell back. The eighth and ninth Ks were clocked at 2: 50 and 2:52, as Power and the two Russians took turns in the lead.

|

| Bolotnikov makes his move. Grodotzki, Powerand Desyatchikov follow. |

Coming out of the last bend of the penultimate lap, Bolotnikov made his move and none of the other three was able to respond. Gordon Pirie, who was well back by this time (he finished 10th), wrote that “As they entered the final lap, Desyatchikov impeded Grodotzki for half a lap, preventing him from attempting to catch Bolotnikov. Then the third Russian, about to be lapped by Bolotnikov, paced his compatriot to the tape.” Running Wild, p. 63) Nevertheless, Bolotnikov showed a supremacy close to Elliott’s over the 1,500 field as he covered the last K in 2:38.6 and the last lap in 57.4 for a clear 4.8-second victory in 28:32.2. Grodotzki earned his second silver with a fine PB, while Power managed to outsprint Desyatchikov for the bronze. Halberg, clearly tired after his great 5,000 run was well back in fifth, while Max Truex followed him in sixth, running 45seconds faster than his previous best.

The Russians ran well as a team—until their dubious tactics in the last lap. Still, I don’t believe those last-lap tactics changed the result. Bolotnikov was clearly the best runner. He ran a smart race and peaked at the right time. As well, he beat his PB by 26 seconds and was only 1.8 seconds outside Kuts’s WR.

- Pyotr Bolotnikov USSR 28:32.2; 2. Hans Grodotzki GER 28:37.0; 3. Dave Power AUS 28:38.2; 4. Akeksey Desyatchikov USSR 28:39.6; 5. Murray Halberg NZL 28:48.5; 6. Max Truex USA 28:50.2.

3,000 Steeplechase

In the summer leading up to the Games, Krzyszkowiak had recently established himself as the favorite, improving his 1959 time of 8:46.4 to 8:31.3 when he beat Sokolov of the USSR (8:32.4). In 1958 the pole had run 8:33.6. He was the fasest steeplechaser on the flat; his hurdling not up to the highest standards.

Three heats were needed to break down the number of entrants from 35 to nine. Sokolov led for the whole of the first heat; his 8:43.2 gave him a five-seconds lead over Swede Tjornebo. The second heat was tighter, but Krzyszkowiak and Muller (both 8:49.6) were in control. Behind them Konov held off George Young, who had fallen with three laps to go. The last heat was tight too, with German 8:34 runner Buhl eliminated with 8:49.6 behind Rzhishchin (8:48.0), Jones and Roelants.

There were three Russians in the final, and it quickly became clear that they wanted to draw out Krzyszkowiak. Konov lead for the first K in 2:45—very fast in the 30c heat (8:15 pace). Krzyszkowiak wisely stayed off the pace, running in the middle of the field. The pace slowed considerably in the second K (3:00.8) as Sokolov took over the lead. This move by Sokolov made Krzyszkowiak move up to third because he feared the Russian most of all. But the Pole had little to worry about. He was able to move ahead on the backstretch of the last lap and finish with a comfortable 2.2 margin. Clearly he was in 8:30 form, and thanks to his speed on the flat was in a class of his own in this race. This race was also notable for the breakthrough in this race for the next Olympic champion in 1964: Gaston Roelants had improved his Belgian record three times in June and July (8:55.4, 8:54.4 and 8:45.8) and had run close to his PB with 8:49.4, to qualify for the final.

1. Krzyszkowiak POL 8:34.2; 2. Sokolov USSR 8:36.4; 3. Rzhishchin USSR 8:42.2; 4. Roelants BEL 8:47.6; 5. Tjornebo SWE 8:58.6; 6. Muller GER 9:01.6.

Marathon

There were a lot of complaints about the heat in Rome. Marathoners, of course, are especially vulnerable to heat. Organizers, rather than scheduling in the early morning, started this race in the late afternoon, when it is much warmer. An additional problem with this start time was that the runners would be finishing in the dark. To accommodate television, “hundreds of torchbearers were put in place along both sides of the road to guide the runners.” (Martin & Gynn, Olympic Marathon, p.231) This lighting combined with the route through historic Rome provided a unique marathon setting.

Apart from one climb at a crucial stage of the race (between 22K and 30K), the course was relatively flat. But runners had to cope with many bends and some very narrow streets. Still, the heat was the main issue.

Perhaps the most fancied runner was Sergei Popov, the current fastest-ever marathoner who had achieved his mark in the 1958 Euros. Dave Power was also expected to be at the front, but he fell ill and didn’t run. Then there was Rhadi ben Abdesselem of Morocco, who had run well in the 10,000. In the final analysis, the winner would be the runner who could best deal with the heat.

The field of 70 started in the Piazza de Campidoglio when the temperature was 23.2C. After a chaotic first few Ks, when the massed runners had to dodge monuments and cross uneven piazzas, Arthur Keily of Great Britain and Aurele Vandendriessche of Belgium led. Close on their heels were two North Africans, Abebe Bikila of Ethiopia, who was running barefoot, and Rhadi of Morocco. These four runners led the field through 5K (15:35) and 10K (31:07). While Keily and Vandendriessche took turns leading, Bikila and Rhadi were happy to follow closely. They passed 15K in 48:02.

There were big changes in the next 5K. At 20K Rhadi and Bikila (1:02:39) had almost a 30-second lead. Vandendriessche (1:03:05) and Keily (1:03:20) had lost a lot of ground. (I question this official 5K time as I do subsequent ones: a jump from 15:32 pace to 14:37 pace, seems unlikely at this stage of the race.) And behind the first four in 1:03:41 were Popov of the USSR, Magee of New Zealand, Kunen of Hommand and Bakir of Morocco. And over the next 5K two of this group, Popov and Magee, moved into third and fourth places, but they were 1:24 behind the two leaders. Keily was hanging on to fifth place, but Vandendriessche was falling back and soon abandoned the race.

The gap between the two leading pairs increase to 2:23 by 30K. (According to the official 5K splits, Bikila and Rhadi completed this uphill stretch in 13:42!) In fifth and sixth places were another pair, Bakir and Mihalic of Yugoslavia (1:37:51). Magee, who had shadowed Popov to move through the field early on, now escaped the Russian at a drink station. Now running on his own, Magee gained a little on the leading pair, passing 35K in 1:52:29, 2:02 behind the leaders. Moving up to fifth Vorobiev of the USSR now had Popov in his sights. At this stage of the race, Magee was running faster than anyone else. In the next 5K he closed the gap to 1:26, as Bikila and Rhadi passed 40K in 2:08:33.

|

| Bikila and Rhadi duel along the Appian Way. |

Shortly before 40K, Rhadi tried unsuccessfully to break away from Bikila. Bikila himself waited until the last 500 to make his effort; Rhadi was unable to respond and allowed the Ethiopian to build a 24-second lead by the finish. Bikila’s time of 2:15:16.2 was just 0.8 faster than Popov’s World Best. Also, Bikila was the first to break 2:20 in an Olympic marathon.

Behind the two North Africans, Barry Magee finished strongly for the bronze. Behind him Vorobiev comfortably beat his compatriot Popov. It is worth noting that four North Africans finished in the top eight—one of the first indications that North African distance runners were to dominate the sport in years to come.

1. Abebe Bikila ETH 2:15:16.2; 2. Rhadi ben Abdesselem MOR 2:15:41.6; 3. Barry Magee NZL 2:17:18.2; 4. Konstantin Vorobiev USSR 2:19:09; 5. Sergei Popov USSR 2:19:19.8; 6. Thyge Torgerson DEN 2:21:03.4.

4 Comments