Profile: Gaston Roelants

b. February 5, 1937

1.74/5’8 67kg/147lbs

|

Very few runners have achieved as much success as Gaston Roelants. For 15 years, from 1960 (4th in the Olympics) to 1974 (3rd in the Europeans), this Belgian athlete was at the very top of his sport. And amazingly he excelled in five different areas of running: he was the 1964 Olympic gold medalist and WR holder in the steeplechase; he was a four-time winner of the International Cross-Country Championships; he was European silver and bronze medalist in the Marathon; he ranked consistently high in world rankings for the 5,000 (twice in the top six) and 10,000 (five times in the top six); and finally he set four WRs for long-distance track races (One Hour and 20K).

His success was based on a lot more than just natural ability. He worked hard, especially in his early years, to develop endurance and strength. With the guidance of his coach, Mon Vanden Eyde, he perfected his hurdling technique. Further he was a wily and aggressive competitor who raced with a lot of confidence. This confidence was needed as he was not blessed with the finishing speed of many of his world-class opponents. Thus he had to run from the front and break his opponents before the final run-in. Few front-runners have matched his level of competitive success.

-- --------------

Initial Breakthrough

The son of a Belgian farmer, Roelants didn’t start competitive running until he was 17. He ran his first Steeplechase after challenging a friend to a race. His earliest recorded time was a fifth-place 9:55 in 1955. Gradual improvement saw him lowering his time to 9:16.5 by 1958. The next year he reached international level. After finishing a creditable 7th in the San Sebastian cross-country race and winning his first Belgian cross-country title, he was an impressive 23rd in the 1959 International Cross-Country Championships, only 2:01 behind winner Fred Norris. In the ensuing track season he improved his PB twice with 9:10.0 and 9:08.6 before running a national record of 8:56.6 at the end of the season. Still, this breakthrough hardly made Roelants a prospect for the 1960 Rome Olympics.

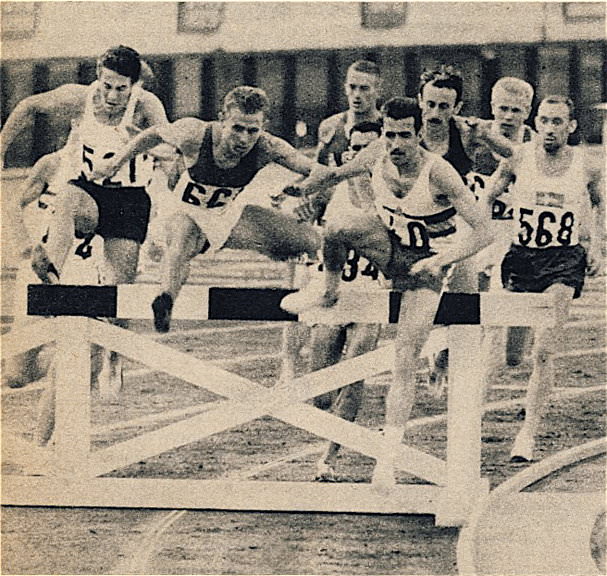

| Hurdling cross-country style. |

But his rapid improvement continued with a stunning second place in the 1960 International Cross-Country Championships at Glasgow behind Rhadi of Morocco. Roelants’ new-found confidence was soon evident in this race as he was the only one to stay with Rhadi’s early break that found them 12m ahead by 2.5K. The experienced Rhadi (11th in 1958 and 8th in 1959) and Roelants soon had a eight-second lead and by 7K they were 20 seconds ahead. At this point Roelants himself started pushing the pace and got away from Rhadi, thanks in part to some hurdles that favoured his steeplechasing skills. Rhadi, however, never allowed the upstart Belgian get too far ahead, and a duel similar to the one the Moroccan would have with Abebe Bikila in the Rome Olympic Marathon evolved over the last Ks. With 1K to go, Roelants tried again to break the Moroccan. Rhadi allowed Roelants a short lead but then delivered a coup de grâce, blasting past and reaching the tape seven seconds ahead. The two runners were in a class of their own; the third finisher, John Merriman, was 42 seconds back. With his second place, Roelants instantly gained worldwide recognition.

1960 Rome Olympics

Roelants’ improvement soon showed on the track as he improved his Belgian record three times in June and July (8:55.4, 8:54.4 and 8:45.8). With his 10.8-second breakthrough to 8:45.8, the question was now whether he could reproduce his best form when under pressure in the Olympics. Of course, he had already shown in the International Cross-Country Championships that he could deal with big-race pressure, but the Olympics would be a much tougher test.

In the Rome Olympics, he had to beat an 8:34 steeplechaser to reach the final. Running close to his PB with 8:49.4, he held off a diving Hermann Buhl of Germany by 0.2 of a second for the third and final qualifying place in his heat. He was one of the nine finalists who lined up in 30-degree heat two days later. That he went with the early breakneck speed of the Russians says a lot about the racing attitude of this young and relatively inexperienced Belgian. He clearly wasn’t daunted at all by the big occasion.

The three Russians’ plan was to take the kick out of favorite Krzyszkowiak, who was the WR holder at 8:31.4. The first K was at breakneck 8:15 speed (2:45); nevertheless, Roelants was up there with the leaders. He even took the lead when the Russian Konov cracked with three laps to go. Despite losing the lead the lead in the next lap, he was still with the three leaders with two to go. But the early pace was telling on him, and he was soon running on his own in fourth as Kryszkowiak raced away from the two remaining Russians to claim gold in 8:34.2. Roelants was still strong enough to hold on to a clear fourth (8:47.6), just 5.4 seconds short of the bronze medal. Behind him there was an 11-second gap to the fifth finisher Tjornebo. Later he claimed that he could have been second or third, but not first: “I was new. The Russians sent out a man to kill off the competition. But I did not know that. I thought I couldn’t let him get so far ahead, so I stayed with him.” (Sports Illustrated, July 17, 1967)

At the age of 23, Roelants had now proved himself world class in two areas—the steeplechase and cross country. After four years of steady improvement, he had in the last two years improved dramatically. As the Track and Field News reported, Roelants had “bettered nine minutes for the first time in 1959.” (October 1960) But it was not just a breakthrough in time. By finishing second in the International Cross-Country Championships and then 4th in the 1960 Olympic steeplechase, he had shown the qualities needed to compete well in major races.

Consolidation

The next year saw more improvement in the Steeplechase. But first he was again in contention in the 1961 International Cross-Country Championships. This time Basil Heatley was his rival at the front. On the second of three laps, Heatley broke away on a steep hill and opened up a nine-second gap at 5K. But Roelants was back in the lead at 9K. The strength of Heatley finally broke Roelants completely, and he finished 92 seconds behind Heatley in 11th place. Still, he had again made a spirited effort to win. On the track, he reduced the Belgian Steeplechase record by 7.8 seconds over three races (8:44.6, 8:43.2 and 8:38.2). In the 8:43.2 race in Germany, he was beaten into second by American Charlie Jones; it would be his last Steeplechase defeat for five years. He also ran several 5,000s, but was unable to break 14:00, his PB being an early-season 14:00.2, which ranked him 18th in the world for 1961.

Double Champion

|

Roelants’ relentless improvement led to his first two great international victories in 1962. After winning the Belgian and Hannut cross-country titles, he finally won the International Cross-Country Championships. This time Roelants was less aggressive in the early stages. He let Rhadi rush into the lead and didn’t appear near the front until after a mile. Once in the lead, he stayed just a few seconds ahead until just after halfway. Then he moved away. With a mile to go he had an 18-second advantage. He was thus able to jog comfortably across the finish line. It was a masterful display of front-running. He was now a stronger and a smarter racer.

Clearly in the best form of his career, Roelants went on to a busy track season of 24 races. He began with five low-key races and then finally broke 14:00 with a 13:57.2. He didn’t run steeplechases until mid –June and even then they were low-key. In August he was rarely racing at his peak, his times fluctuating from 8:54 to 8:45. A Belgian record of 29:18.6 nevertheless confirmed his endurance.

He came to Belgrade for the September European Championships with a best time of 8:40.4 set back on June 28. After easily qualifying for the final in a brisk 8:42.0, he once again came through in a big race, leading from the start and enjoying a comfortable five-second lead at the tape. so he was European champion with a PB and national record of 8:32.6. This time, achieved when it really mattered, was a personal improvement of 5.6 seconds and was within 2.2 seconds of Kryszkowiak’s WR. Track & Field News called Roelants’ run “The greatest one-man show in the history of the event.” (Oct. 1962)

First World Record

Yet again Roelants was involved in a duel at the front of the 1963 International Cross-Country Championships race. This time he encountered a runner reputed to be the toughest in the business: Roy Fowler. The flat and fast course suited Roelants, so after 2K he was able to leave all but Fowler in his wake. Fowler grimly held for the next 9K. Over the last K, Fowler tested Roelants three times. Finally, 20m from the tape, the Brit put in a devastating kick that left Roelants without an answer and with another second place in this race.

With no major games to prepare for, Roelants’ obvious target for the 1963 track season was the 8:30.4 Steeplechase WR. After a slow start, he rounded into form at the Helsinki World Games with an 8:39.2 victory. Then after four more steeplechase victories in July (8:56.6-8:40.8), he PB-ed with 8:31.2 on August 6 in Stockholm--only 0.8 off the WR. Seventeen days later he ran 8:33.6 in Helsinki. He finally achieved his goal on his home Leuven track on September 7. Although it was an international meet, he had no real competition as he became the first man ever to run under 8:30, clocking 8:29.6 and winning by 17 seconds. After steady annual improvement each year since 1955, the Steeplechase WR was finally his.

And to complete the year, he took advantage of the best form of his life to run PBs over 5,000 (13:45.6) and 10,000 (29:07.2). He now had to prepare for the biggest test of his life: the 1964 Olympics.

Tokyo Build-Up

Perhaps it was a mistake to go to the USA in the winter, but after just one indoor race in Los Angeles (a Two-Mile victory in 8:41.4), he developed an injury in his next race in Portland and was unable to finish. At first it seemed that this injury was not serious because back in Europe he won four cross-country races including Hannut and Martini Cross. But the injury came back with a vengeance in the International Cross-Country Championships. As usual, he lead the field after the first of five laps. But after another lap he had dropped to second and looked in pain. In the third lap he slowed, and despite being “waved back in the race by rather irate Belgian officials,” (Times, Mar. 23, 1964) he had to abandon the race.

Roelants didn’t race again for almost three months. But in his first race back, a 10,000 in Rennes, France, he ran a PB and Belgian record of 28:57.2 behind Jean Fayolle. A week later he PB-ed in a 5,000 race in Zurich with 13:43.4. Then another week later, in his second Steeplechase of the season, he ran an encouraging 8:31.8 in Oslo. Roelants was clearly in Olympic form. Throughout July and August he ran well, winning all his races. But after another 10,000 PB on August 29 (28:41.8), he again sustained a leg injury. The Olympics were only 47 days ahead.

Tokyo

|

| In his usual position at the front. |

He was unable to race again before his Olympic heat. He told Alastair Aitken, “I did not start my hard training…until only one week before the Belgian team left for Tokyo, and then I covered only about 50-55K a week.” (highgateharriers.org.uk, 2012) The closest he came to competition before the Olympics was a 5,000 time-trial in Tokyo a week before his heat. The14:01.4 run alleviated a lot of his fitness concerns.

Roelants felt that his enforced lay-off upset his pace-judgment. He started his heat too fast in running 8:33.8 to win by two seconds. But disaster struck during a light workout the day before the final. While doing some hurdling, he hit his shin just below his right knee several times and thought he had ruined his chances of running in the final. However, four hours of urgent treatment took away the pain. He was on the start line the next day: “In the final I didn’t feel any pain at all, and just to make certain that I did not hit a hurdle in this race, I hurdled over them very high and did not hit one.” (Aitken, 2012)

After a cautious start, Roelants moved to the front just after the first K (2:52). Then he “just went.” By 2K his lead was 7.4 seconds. At the bell he still had a 50m lead, and despite tiring, held on for a 1.6-second victory ahead of fast-finishing Maurice Herriott. He was Olympic champion. Despite all his problems, he still ran his fastest Steeplechase of the season (8:30.8), which was very close to his WR. Yet again he was able to rise to the occasion. It must have been an incredibly hard race for him.

Ron Clarke has made some interesting points how Roelants coped with front-running in this race: “It was intriguing to see Gaston’s coach signaling messages to the Belgian from outside the track. The coach had a board on which he wrote how many runners were in the group behind Gaston and how far behind they were. As a front runner myself, I could appreciate how valuable this information could be.” (The Unforgiving Minute, p.115)

Steeplechase World Record

|

| Roelants follows Kip Keino. |

There was no let-up after his Olympic triumph. Roelants was quickly back winning road and cross-country races. One setback was in the 1965 International Cross-Country Championships; after running with the leaders early on, he was forced to drop out. His track season started late, on June 29, with a 13:53.6 third place in a 5,000 in Zurich. After a steady 29:13.0, he broke his 5,000 PB in Stockholm with 13:34.8 after trying unsuccessfully to stay with Clarke and Keino. After another three flat races, Roelants ran his first Steeplechase of the season on July 22 and clocked an impressive 8:35.4. Six days later in Stockholm he ran very close to his WR with 8:30.0. And then just over a week later in a solo run in the Belgian championships in Brussels, he ran a brilliant 8:26.4 to improve his WR by 3.2 seconds.

The very next day, in the same meet, he also ran a PB and Belgian record for 10,000 (28:24). A week later he showed some speed to PB in the 3,000 with 7:48.6 on his home Leuven track. To finish off yet another brilliant track season, Roelants broke the European 10,000 record in the European Cup Semi-Final in Oslo. His 28:10.6 ranked him second in the World for 1965 behind Clarke’s 27:39.4. With no major meets in 1965, Roelants had focused on the clock. In 15 races over two months, he had reduced his PB times significantly: 3.2 in the Steeplechase, 22.6 in the 3,000, 8.6 in the 5,000, and 31.2 in the 10,000. In view of his fast flat times, he started to talk of running an 8:20 Steeplechase.

Build-up for Budapest

But in 1966 he suffered a major setback in the European Championships. His year started well enough with an indoor win at the Millrose Games in New York (2 Miles in 8:40.6), a couple of international cross-country wins (Hannut and Blankenburghe), and three comfortable victories in South Africa. This year he boycotted the International Cross-Country Championships to protest the new ruling by his national governing body that limited runners to three major races a month. Then at the end of May he went to California, where he won a Steeplechase, was second in a Two Miles and fifth in a 5,000 in 13:46.2. A couple of weeks later, he started the European season on June 30, two months prior to the European Championships. So far his year had been quite demanding, with two intercontinental trips and a lot of track competition. In retrospect, this busy program might have been the root cause of his disappointment at the Euros.

He was clearly in top form in July, when he ran 8:27.2 in Stockholm. A week and two more races later, he ran a fast 28:20.8 10,000 behind Ron Clarke (27:54.0) and in front of Haase and Gammoudi. In the six weeks before the Euros, he ran and won four more steeplechases (8:40,8, 8:35.2, 8:35.6, 8:36.2). It seemed that he was in excellent shape to retain his European Steeplechase title and hopefully also win the 10,000, for which he was the second-fastest entrant.

1966 Euros

|

| Last water jump in the 1966 European Steeplechase.Kudinsky and Kuryan are about to overtake Roelants. |

The 10,000 was his first race in Budapest. He was with the lead group until three laps to go but then faded badly to finish in 8th with 28:59.6, 33.6 seconds behind the winner Jurgen Haase. Nevertheless, Roelants qualified well in the Steeplechase with a fast 8:33.8. His main competition in the final looked likely to come from the USSR (Kudinsky and Kuryan) and France (Texereau). Roelants didn’t lead until after four laps, the first K having been run in 2:51.0. He was soon on his own, passing 2K in 5:41.8, and had a 15m lead at the bell. But Kuryan and Kudinsky, who had moved into second and third, began to chase him down. And by the water jump they had almost caught him. Roelants had no answer as they both swept past. Kudinsky, running a 63 last lap, was only 0.2 outside Roelants’ WR at the tape with 8:26.6 and Kuryan ran 8:28.0 to Roelants’ 8:28.6. Perhaps the hard 10,000 four days previously had sapped a little of his strength. It was the first time in 45 races that he had been beaten in the Steeplechase, but it had taken almost a WR to beat him.

“For maybe 2,500m I ran very strong,” he told Sports Illustrated, “but at the end I am like lead. I am numb. I feel nothing and so I am passed by two men and the Russian wins. I was ahead of my WR time most of the way, but I didn’t have anything left.” (July, 1967)

Two months later, Roelants made amends for his unexpected defeat. On his home track he tried a new event: the One Hour. This is quite a different event from his Steeplechase specialty, and although closer, still quite different from his longer cross-country races. Starting rather slowly with a 14:47 first 5K, he found a good rhythm and reeled off 5Ks in 14:27, 14:19 and 14:33 for a WR time of 58:06.2 at 20K. This beat Ron Clarke’s WR set the previous year by 43.4 seconds. Roelants continued to finish the race in another WR: 20.664K—443m better than Clarke’s One Hour record.

Cross-Country Champ Again

Clearly his European Steeplechase setback wasn’t enough to bring up thoughts about retirement. Just before his 30th birthday, Roelants ran second in the Sao Paulo New Year’s Race. In March he dominated the 1967 International Cross-Country Championships field with a superb 17-second victory over cross-country specialist Tim Johnston. The tenacious Johnston tried hard to hold on to Roelants, but two sustained bursts broke him. Roelants started his 1967 track season with a couple of Steeplechase wins in California (8:39.8, 8:45.4) and a fifth-place Two Miles (8:38.3). Back in Europe he did not show his best form finishing 3rd in the Helsinki Games 5,000 (14:02.2) and then losing a Steeplechase to Kogo of Kenya.

It wasn’t until August that his good form returned. In Oslo he ran the world’s best 10,000 time of the year (28:26.6), representing Benelux against Norway. Three very fast Steeplechases followed: 8:32.8, 8:28.6 and 8:31.0. Finally, he went to Mexico for the Pre-Olympic meet. The day after finishing third in the 10,000, he won the Steeplechase in 8:57.8, beating Kuryan. He then tackled the Marathon. His 2:19:37.4 at altitude astonished everyone and left Roelants himself brimful of confidence. “I found the Marathon so easy,” he told Neil Allen. “I never found the altitude a problem.” (Times, Oct. 23, 1967) However, there were claims later that the course was short, (Times, May 11,1968) so Roelants was probably given a false impression about running a marathon at 2,420 m (7,940 ft) altitude.

Mexico Olympics

|

| Roelants (left) in the Mexico City Olympics. |

His Olympic year didn’t start well. After winning the Sao Paulo and Cinque Milini races, he suffered a jarred heel during the International Cross-Country Championships in Tunis and finished 31st, the lowest placing in his 17 starts in this race. He had to be carried to the dressing room afterwards, but he recovered to run 8:39.4 and 8:38.6 Steeplechases in June, after which he won the event in the World Games in Helsinki with a slow 8:41.8. The next day he was fourth in the 10,000 in a respectable 28: 46.2. In July, he rounded into form with a fine 8:29.2 Steeplechase in Italy.

But his Olympic races in Mexico City were disappointing. He was only seventh in the Steeplechase. After a conservative start, he was fourth at 1K behind Kogo, Biwott and Villain (3:04.2). On the fifth lap he moved into the lead and took the field past 2K in 6:03.2. At the bell he was third but still in the race, but when American Young made his effort at 300, Roelants was unable to respond. He finished seventh in 8:59.4, 8.4 seconds behind winner Biwott. He was seen limping afterwards, but he still lined up for the Marathon four days later.

As was his wont, Roelants was in the lead group from the start. After they passed 15K in 50:26, Roelants began to push the pace and covered the next 5K in 15:36—the fastest 5K of the race. At 20K (1:06:02), he was at the front with Tim Johnston of Britain. But this effort proved too much for him as he soon dropped back. In the next 5K he lost over half a minute on the leaders and was back in ninth. At 30K he was 2:05 back of the leader in 8th (1:41:25), having slowed to 17:41 5K-pace from 20K to 30K. His chance of a medal was gone, but he held on for 11th place (2:29:04.8). Mexico had proved a disappointment; he was not accustomed to seventh and eleventh places. Clearly he had lacked the thorough altitude conditioning needed to be a medal contender.

Evergreen

After 1968, Roelants virtually abandoned the Steeplechase. In the next eight years up to his 40th birthday, he ran only three. Then, in his first year as a master (1977) he ran three before winning the World Masters title. This decision to give up steeplechasing must have been taken because of his knee injury from hurdling. As well he must have seen that runners with better 3,000 speed were taking on the Steeplechase. By 1976, his 8:26.4 WR had been reduced to 8:08 by Anders Garderud, whose 1,500 best was eight seconds faster than Roelants’.

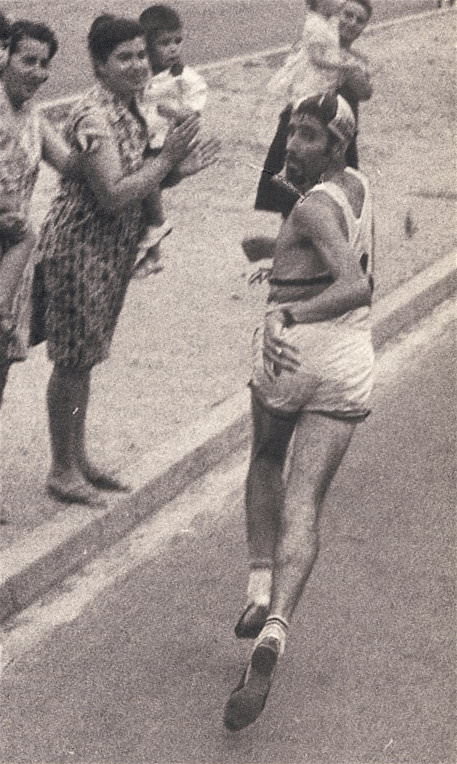

|

| 1969 European Marathon: "in trouble and looking back." |

In 1969, at age 32, Roelants managed to win the International Cross-Country Championships for the third time, reduce his 5,000 PB, and win a silver medal in the Euro Championships Marathon. In the International Cross-Country Championships in Scotland, he broke away from Dick Taylor of England after 5 1/2 miles, “haring up the steeply sloped parkland as if he was on the flat to gain a lead of 15 seconds.” (Times, March 24,1969) His margin at the tape was 19 seconds. On the track, he had a gentle start with five 5,000s over 14:00. But at the end of June he clocked 13:49.6 and 28:21.2. His new 5,000 PB of 13:34.6 came in early August, some five weeks before the Euros.

In Athens he first ran the 10,000, in which he had an epic battle with the eventual winner Jurgen Haase. He was well aware that the East German had a far superior kick, so after a slow start in very humid conditions, Roelants tried hard to break Haase by injecting bursts along the straights. But Haase could not be dropped, and the inevitable happened on the last lap, where Haase ran 55.8 and Roelants fell back to fifth, 8.2 seconds behind Haase.

Five days later, Roelants lined up for the Marathon. He didn’t wait long to take the lead. He was the only one to chase down the early leader Farcic, and after 10K he was out on his own. It was a lonely race. At 30K he was 1:19 ahead of Britain’s Ron Hill. But then he began to lose ground. He lost 19 seconds in the next 5K. By this point he was in trouble and was looking back constantly and almost walking at times. Hill, finally caught him 800m before the stadium. Nevertheless, his 2:17:22.2 for a silver medal was impressive PB for a steeplechaser.

Two Quiet Years

|

| Roelants forcing the pace in the 1970 International Cross-Country race.Trevor Wright, Mike Tagg and DIck Taylor chase him. |

In 1970, he almost won the International Cross-Country Championships again. Over a heavy course in Vichy, France, he moved up to the two leaders, Mike Tagg and Trevor Wright in the middle of the race. The three were together near the finish, when Tagg and Roelants dropped Wright. With 400 to go, the two leaders bumped and Roelants lost a shoe. This enabled Tagg to win by two seconds. Despite claims by Roelants that he had been deliberately obstructed, there was no change in the official result. The angry Roelants had to accept his third second place in this race.

The rest of the year was relatively quiet; in fact he didn’t compete at all from July 2 to September 5. He started back with an ambitious 30,000 in London (See Great Races #20). After leading through 10,000 in 29:59, he lost contact with the leaders by 15,000, and in obvious pain dropped out before 20,000. His best race of the year was a 28:25.4 10,000 in Koblenz, when he finished second to Philipp of West Germany.

|

| Roelants (5) races over 30,000. Tim Johnston leads winner Jim Alder and Ron Hill. |

He had a quiet winter over 1970-1, but he did run the International Cross-Country Championships, finishing 12th, 1:02 behind winner Bedford. His track season was busier with five fast 10,000s in June and July (28:39.4, 28:56.8, 28:34.0, 28:22.0, 28:48.8). Then to sharpen up for the Euros, he ran two 13:40 5,000s. As he had done two years earlier, he tackled both the 10,00 and Marathon in Helsinki. In the 10,000 Roelants had one of his worst races, falling off the pace after 2K and dropping out after 7K. In the Marathon he was much more in the race. He was soon out in front with his younger team-mate Karel Lismont. They were eventually joined by Trevor Wright of Britain. At 25K the trio had a 70m lead on Hill and Kirkham. Soon after this Roelants made his move on a downhill stretch and opened up a 30m lead. But at 34K Wright and Lismont passed him, and later Hill and Kirkham took him as well. He finished in fifth with 2;17:48.8, 4:40 behind the winner Lismont.

Third Olympics

The Munich Olympic Games was now looming. And what better way to prepare for them than a fourth International Cross-Country Championships win? This time it was at Cambridge, where he won with a clear 18-second margin over Mariano Haro and Ian Stewart. He made his effort around 7K when leading with Haro and Stewart. Stewart fell back and Haro was broken 2K later. Roelants’ dominance was underlined by the fact that he had to stop at one point after nearly losing a shoe.

Soon into the track season he ran 28:20.4, this time behind Haro. But his focus was on the Olympic Marathon, and to this end he ran a 26K road race in Italy, which he won. But his race preparation for Munich was mainly on the track: three 10,000s and three 5,000s. In one of the 10,000s, he ran his best ever time of 28:03.8, a remarkable PB for a 35-year-old.

In the Olympic Marathon, Roelants was with the leaders at 10K (31:15). And he was in a pack of seven runners just five seconds behind leader Frank Shorter at 15K (46:21). Then he started to lose ground, dropping back to 11th and 48 seconds behind the leader Shorter. Soon after this he dropped out. It was a big disappointment.

Roelants’ last major setback had been in the 1969 Euros, when as the WR holder, he was beaten into third place in the Steeplechase. After that he went out and broke the One Hour and 20K WRs to atone for his bad loss. He did exactly the same this time after his Munich disappointment. Just ten days after his Marathon DNF, he lined up at Bruxelles for another attempt at improving his WRs for 20K and One Hour. Team-mate Willie Pollenius took the early pace, passing 10 Miles in a new WR of 46:04, Roelants was only 15 seconds behind at this point. He reeled off 5,000s in 14:19, 14:25, 14:32 and 14:28 to clock a new 20K WR of 57:44.4 and he reached 20.784m for One Hour, another WR. This was in improvement of 21.8 seconds for 20K and 120m for One Hour. He had proved himself a world-beater yet again.

Still Miles To Go

In 1973, it looked like his career was winding down. He ran well in the World Cross-Country Championships with eighth place, only 27 seconds behind winner Paivarinta. But his track season was low-key. He did win a couple of international races, but generally he finished down the field. His best 1973 times were 13:44.4 and 28:27.4 (30th in world rankings). He also ran a rare steeplechase to win the Belgian title with 8:40.4. This was 26 seconds slower than Rono’s new WR set that year.

But he wasn’t done yet. After his 15th run in the 1974 World Cross-Country Championships (14th place), Roelants set his eyes on his third European Marathon. In the build-up he returned to the Steeplechase, running two respectable times of 8:36.28 and 8:35.4. He also ran a couple of 10,000s in 28:41.4 and 28:24.83 (faster than his world-leading time in 1967!).

In the European Marathon, Roelants was up with the lead group of seven at 10K (32:44). At 15K the fast pace of Thompson had thinned the lead group to four. Roelants was still there. At 20K (1:02:12) he was still at the front, but at 25K he was 1:36 behind Thompson and 1:20 behind Lesse. Still a medal looked likely as he had 30 seconds on Bernie Plain in fourth. At 35K he was 2:23 behind Thompson and 1:43 behind Lesse, but he was moving away from Plain and now had a 1:23 cushion. Over the last 7K he finished well and earned a bronze medal with 2:16:29.6. He was 3:11 behind the fast–finishing Thompson and 1:32 ahead of Plain. A wonderful run for a 37-year-old.

Masters Competition

Over the next two years (1975, 1976) he kept in good shape; it seems he was waiting for his chance at Masters competition. He ran well in the World Cross-Country Championships both years (10th and 13th), and ran 10,000s around 29:00.

On turning 40, he broke the Masters WR in the Steeplechase twice with 8:43.6 and then 8:41.5. Next he competed in the Masters World Road Race Championships, winning both the 10K (30:37) and the 25K (1:19:59). His final glory came in August 1977 at the Masters World Championships in Gothenburg. He won three titles by enormous margins: 5,000 in 14:03 by 26.4 seconds; 3,000 Steeplechase in 8:56.6 by 24.0 seconds; and 10,000 in 28:57 by 19 seconds. After 19 years of competition, it was finally time to retire.

Conclusion

Gaston Roelants was one of the great front-runners of the 20th Century. Front-runners are noted for record breaking but also for competitive vulnerability in major races. Roelants was able to counter this vulnerability with a combination of tactics, mental strength and physical courage. Thus he won not only Olympic and European Steeplechase titles but also four victories in perhaps the most competitive international race—the International Cross-Country Championships, now called the World Cross-Country Championships. Of course, Roelants didn’t win all his major races, but he was almost always up at the front fighting hard for victory. A champion if ever there was one!

5 Comments