Ronnie Delany Profile

b. 1935

|

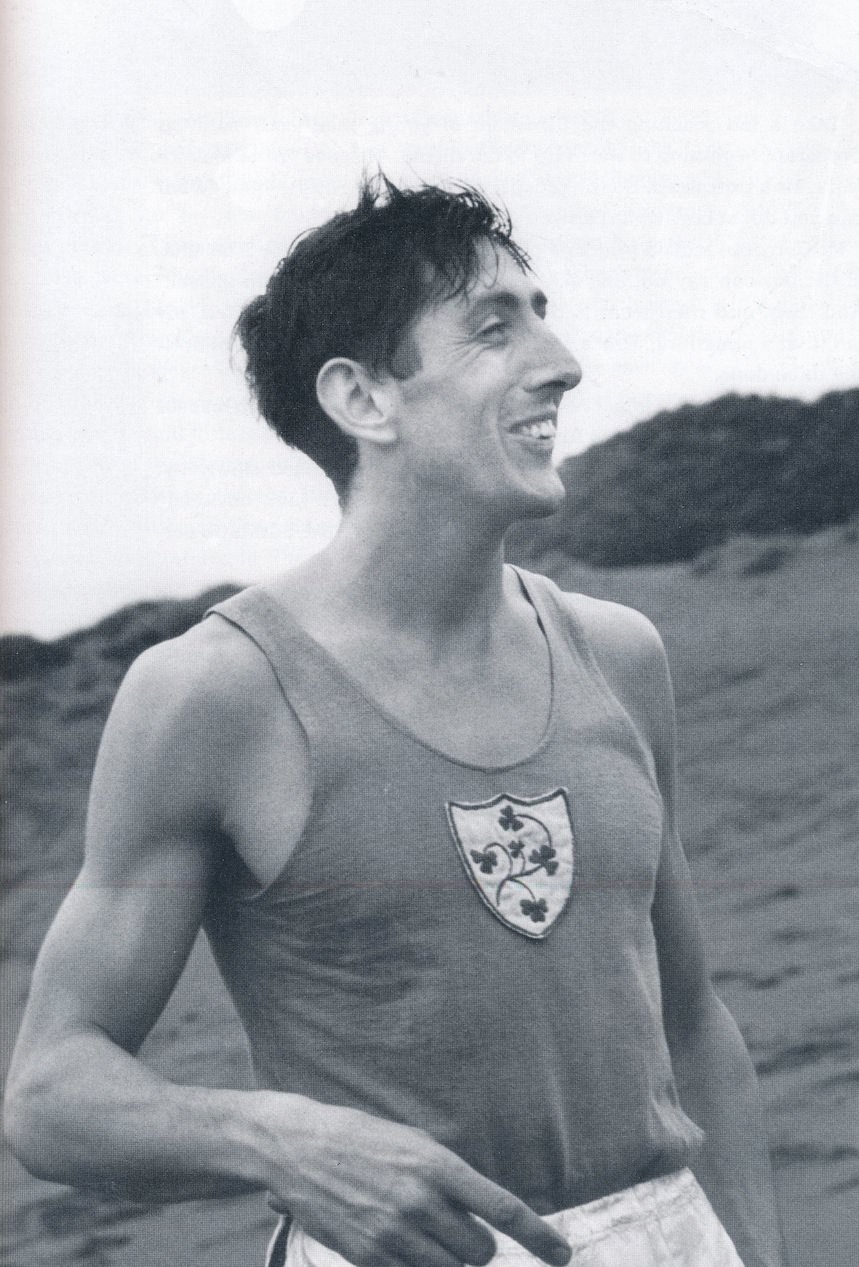

Irishman Ron Delany’s development from a 17-year-old 2:04 half –miler to a 21-year-old Olympic 1,500 champion can justly be called meteoric. Of course, he had natural ability, but there were other ingredients in the mix. He had an inner strength that is rarely found in a teenager. This mental focus enabled him to train hard and to race brilliantly. He was also fortunate in obtaining an athletic scholarship to train under Jumbo Elliott at Villanova University in the US. Over two years Elliott trained and raced him to perfection, instilling in him the belief that he was a miler and that he could win at the 1956 Melbourne Olympics. And Delany did just that against a stellar field of experienced runners. Rarely has a middle-distance runner reached the very top so quickly.

But there was another aspect of Ronnie Delany’s career as a runner. His post-Olympic running career continued—on the boards in American indoor meets. Over four seasons (1956-1959) he was unbeaten in 40 races. In that time, although he was never interested in running against the clock, he also beat the world indoor Mile record three times, finally reducing it to 4:01.4. In his autobiography Staying the Distance, Delany underplays this aspect of his career: “The rest of my career [after his Olympic victory] would always be a sort of ant-climax.” (p. 85) This is surprising for his 40–race winning streak must rank as one of the greatest winning streaks of all time, up there with Herb Elliott’s unbeaten record over a Mile. It is a testament not only to his competitive skills but also to his consistency.

Outdoors, Delany also ran in the European Championships twice. As an 18-year-old he reached the 800 final after breaking the Irish National record twice. As a 22-year-old he won the bronze medal in the 1,500, finishing behind Brian Hewson and Dan Waern. Over his career, he broke 4:00 for the Mile three times, twice in world-record races. He ran second (3:58.8) to Derek Ibbotson’s 3:57.2 and third (3:57.5) to Herb Elliott’s 3:54.5.

The last three years of his career (1960 to 1962) saw a falling off of his powers, as injuries took their toll. The one highlight was in 1961 when in front of his Dublin home crowd he took on the 800 Olympic champion Peter Snell. Although he finished third, he set an Irish record for 800 with 1:47.1.

---

Born in County Wicklow in Ireland, Ronnie Delany moved to Dublin with his family when he was six. His family home backed on to a tennis club and a large sports area, all of which he could see from his bedroom window. He soon became an avid tennis player and learned to play hockey and cricket. He says in his book that sport occupied “every free moment in my formative years.” (p. 21) The first race he recalls running was a relay race when he was 12. But most of his running was done to and from school: “I ran to Sydney Parade in the morning and from Amiens Street up the steep incline to Buckingham Street to be on time for school. At lunchtime I raced my brother Joe…in a futile effort to be first home.” (p. 22) All this running helped the athletic careers of both brothers. The elder Joe was a champion long jumper and sprinter and the younger Ronnie watched him win many trophies: “Clearly I did not have Joe’s talent as a schoolboy.” (p. 24)

Young Ronnie’s talent was soon noticed by Jack Sweeney, a math teacher and a track coach. Sweeney persuaded him to enter the Half Mile in the Leinster College Championships. He warmed up in his cricket flannels as he didn’t own a track suit. In a pair of spikes from his dad, he won not only this race (2:06.6) but also the All-Ireland Colleges (2:03.9) and the AAU Youths (2:04.0). Right from the start, Ronnie Delany was winning races: “In a perverse way,” he wrote, “I enjoyed the nervousness of competing, and the butterflies in the tummy that went with it.” (p. 25)

Making Waves

Running was forgotten for the rest of that summer; in fact he didn’t race again until the school sports the following May. He won all his 880 races again, although his times were a little slower, in the 2:06-2:08 range. But this year he continued racing through the summer, and in July his time dropped to 2:04.3. Then in August, after a breakthrough run in a 880 handicap race, where he ran 1:55.5 off a 20-yard allowance, he was invited to run against Seniors for the Irish AAU. He won yet again with 1:58.7 to become the first Irish schoolboy to break 2:00. “I now knew I had a special talent for running,” he has written. “How good I was going to become I had no idea. But instinctively I knew what I had to do. From then on I must specialize in running, give up all my other sports and train as I had never trained before.” (p.26)

To this end, Delany read running magazines to develop a training strategy. He also corresponded with Welsh coach Jim Alford, who in 1951 had published Middle Distance Running and Steeplechasing. Alford helped him learn about fartlek and interval training, but he was all on his own when putting these modern theories into practice. Now out of school, Delany won a cadetship in the Irish Army and enlisted in December of 1953. Although this was a career break, the system was not at all conducive to his running. To the dismay of his father, Delany obtained an honorary discharge. This brave move underlined his desire to succeed as a runner. So instead of a military career he became a traveling door-to-door vacuum salesman, fitting in his training when he could.

In the spring of 1954 he gained access to a local school cinder track, where he was able to carry his speedwork. By June he was ready for competition. He had trained with missionary zeal throughout the winter. Little did he know that his season would lead to a place in the European 800 final. His first race was at the Irish AAU championships. He surprised everyone with a convincing win, using the unanswerable kick that was to be his competitive trademark. As well as winning, he set an Irish record of 1:54.7. A week later he won again in 1:53.7, again using his kick. The idea of developing a kick had come the previous year while he was still in school: “Tactically, on the advice of Jack Sweeney, I had developed a strategy of making one decisive move in the course of the half-mile race.” (p. 26)

International Status

After two more wins in Dublin, Delany went across the Irish Sea to compete at the White City in London. There he came up against the fine British 880 runner Derek Johnson, who was to win a silver medal in Melbourne. The Times reported that Johnson had to “show something of his best form to win as decisively as he did against another…promising Irish runner in R.M. Delaney [sic].” (July 18, 1954) That “decisive win” was 1:52.9 to 1:54.3. Two weeks later back in Dublin he was back to his winning ways, improving his Irish record to 1:53.2.

After such a successful season, he was selected to represent his country in the European Championships in Berne. There he surprised again, not only getting through the heats and the semis to reach the final but also improving his PB with 1:51.8 and then 1:50.2. But those two huge efforts left him exhausted for the final, where he finished last in 2:03.5. Nevertheless, he had shown immense promise as a racer who could also run fast times.

Over the summer, Delany had met several American coaches and athletes and learned about the Irish connection with Villanova University in Pennsylvania. Several Irish athletes had gone there after the 1948 Olympics to train under the famous coach Jumbo Elliott. Delany decided to apply to Villanova, and at the end of the season he was on his way to the USA with a full athletic scholarship. It proved to be a fortuitous move.

The reasons for Delany’s decision to leave Ireland were many. There was little chance of him succeeding as a runner if he stayed in Ireland, where there were no decent running tracks, limited competition and no training facilities. In going to Villanova he would have access to some of the best facilities in the world. At the same time he would be able to get a university education that would see him well back in Ireland after his running career was over.

Freshman

Having trained on his own without coaching supervision, Delany found it difficult at first to be under a coach. Coach Elliott appears to have sensed this and didn’t impose on him too much. In fact, he only expected Delany to attend just three team training sessions a week. But, of course, Elliott needed to establish himself as Delany’s coach. Delany recalls the first time he ran on the track with Elliott watching: “After seeing me run a few laps he took me aside and gave me some critical advice on my arm action (‘too jerky’), head ( ‘rolls too much’) and shoulders (‘too stooped’). Listening to him I began to wonder how I’d managed to run at all up to then with all my deformities.” (p. 40) At the same time Elliott told him that he would make a good miler—an amazingly prophetic opinion as it turned out.

Delany soon crossed swords with Coach Elliott when he discovered he would have to race every weekend through the indoor season: “I wanted to run my best races for Ireland in her green international singlet and not leave my talent and strength in the smoke-filled indoor arenas of America.” ( p. 52) Elliott “nearly blew his top” when Delany complained and told the young Irishman in no uncertain terms that he would run where and when his coach required.

Of course, Delany soon came to respect Elliott profoundly, finding him especially helped when preparing for competition. And he reveled in the dedication and enthusiasm of Elliott’s squad. He also became close friends with Charlie Jenkins, a Villanova 400 runner who would win two Olympic golds in 1956. Jenkins, a year older than Delany became his training partner despite their different events. Delany recalls, “We worked together in training, pushing each other to the limits of our endurance. We helped each other in time trials and by critical advice. We were of the same mould.” (p. 46) At the start, Delany still thought of himself as an 800 runner, so it made more sense to have a 400 training partner. When Delany began to focus on the longer distance, Coach Elliott still let Delany train with Jenkins and develop his speed.

Indoors

|

|

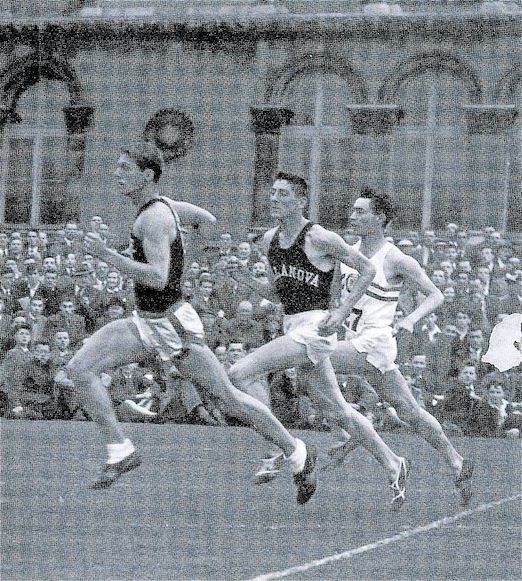

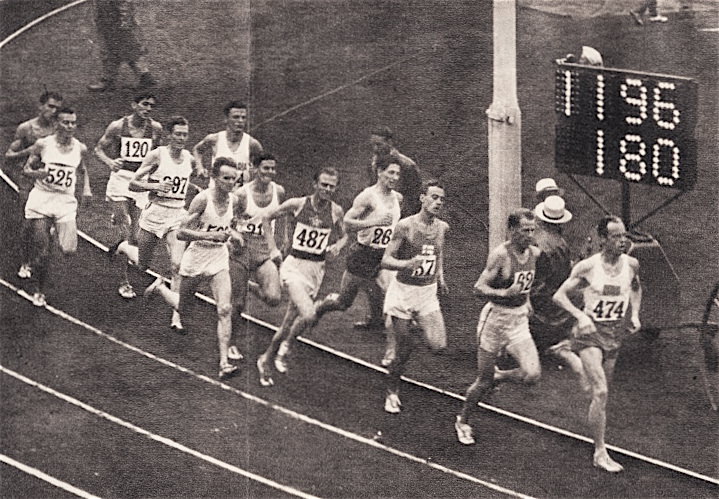

This captures the atmosphere of a indoor meet and shows a typical Delany victory. |

It was not long before Delany became acquainted with a board track. At the Villanova stadium a wooden indoor track would be placed outdoors early in December in preparation for the upcoming indoor season. Delany, who had never run on the boards, found them difficult at first, but with the help of Charlie Jenkins he proved quick to adapt. This was evident in his first indoor race in Boston, a 1,000 Yards. But he was in for a shock at the start: “The race began and it was a nightmare. I tried to secure a good position at the first bend but…Carl Joyce unceremoniously belted me aside as he came up on my inside. Every time I moved up alongside a runner I got the same treatment. Biff, bang, wallop—I wondered if this was boxing or track.” (p.49) Despite all this he managed to get to the front about 100 yards from the finish and hung on for a win in a new track record time of 2:10.2. After the race, Coach Elliott came up to him, congratulated him and then said, “Boy, have you got a lot to learn.” (p. 50) Soon after Elliott spent an afternoon schooling him on how to protect himself in indoor races. Following this, Delany completed his indoor season with four wins out of six races. The only people to beat him were Arnie Sowell, Tom Courtney and Audun Boysen.

As a Freshman, Delany did not compete outdoors for Villanova, but he did have one race before returning to Ireland for the summer. This was an 880 in the LA Coliseum Relays. Up against Lon Spurrier, Mal Whitfield and Tom Courtney, he ran what he called toughest race so far. Amid a flurry of elbows and fists, during which Sowell was knocked off the track, Delany managed to survive and finish second behind Courtney. Then Courtney was disqualified for cutting in, so Delany had another victory. His time of 1:50.4 was a PB and an Irish record.

|

|

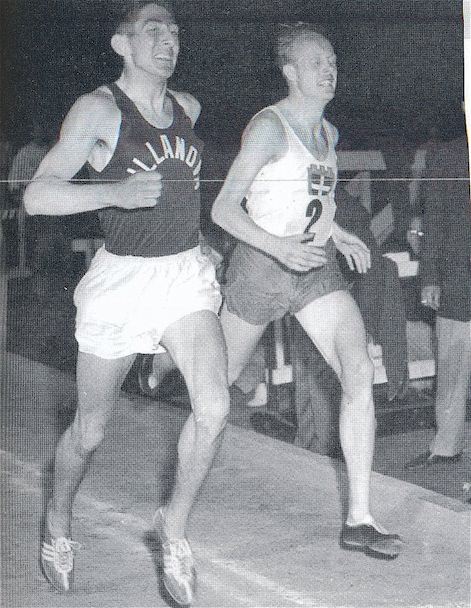

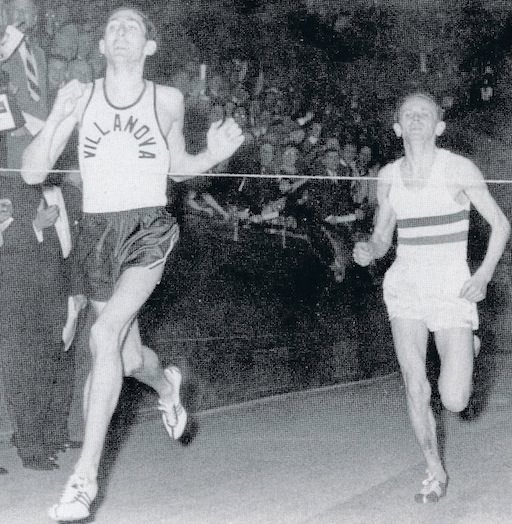

Running on grass in Ireland and wearing his Villanova vest, Delany defeats Johnson (in white). |

Back home for a break rather than for the European track season, Delany still ran a few races low-key races, except for an 800 in Brussels, where he was beaten by Roget Moens into second (1:50.6), and an 880 in Dublin, where he beat Derek Johnson in another PB and Irish record (1:50.0).

Sophomore

After running cross-country for Villanova in the fall of 1959, Delany ran the Mile for most of the 1956 indoor season. Despite originally training to run the 1,000, he had a perfect season with eight consecutive wins. There was one fast time of 4:06.3 in beating Wes Santee. However, these races were generally tactical affairs averaging above 4:10, and the crowds often booed the runners for not trying to beat 4:00. Delany was often greeted by boos when he breasted the tape. This was not easy for the 19-year-old, and he was relieved when the indoor season was over.

Before he could focus on qualifying for the December Olympics, he ran relays for Villanova during March. Then in April he ran a PB Mile in 4:04.9 before he came up against some of the best in the world: Jim Bailey, John Landy, Gunnar Nielsen. In May he experienced three losses that put a dent in his Olympic hopes. First he was totally dominated by Bailey (3:58.6) and Landy (3:58.7) when running 4:05.5 in Los Angeles. He did even worse a few days later in Fresno, when he ran only 4:09.2 to Landy’s 3:59.1. Then he was beaten into second by Arnie Sowell in the IC4A 880, running 1:52.0.

Finding Olympic Form

|

|

Compton Mile 1956. Delany passes Gunnar Nielsen to record his first sub-4. |

Just when things were looking bad, Delany found his form in June. Perhaps he benefited from some help that John Landy gave him after their two Mile races. (“He told me that I kept my shoulders too tense, and he taught me how to relax. He talked to me and encouraged me,” he told the press later) In the Mile at the Compton Invitational, he was up against World 1,500 record-holder Gunnar Nielsen, as well as top American milers Fred Dwyer and Bobby Seaman. Coach Elliott had advised Delany to keep back from the lead but to stay within 10 yards of the leader.

This advice was relatively easy to follow as the race was uneventful until the bell. At this point, Nielsen blazed away and Dwyer and Seaman held on to him. With 200 to go, Delany slipped by the two Americans and moved right up behind Nielsen. Coming into the straight he was on the Dane’s shoulder but could not get by. It was only at 40 yards from the tape that he managed to take the lead for a 0.1-second victory. With a fine 3:59.0 (a 5.9-second improvement) he had become the seventh person to break 4:00 after Bannister, Landy, Tabori, Chataway, Hewson and Bailey. The next day he ran a PB 880 of 1:49.5. His winning ways continued in the NCAA Championships 1,500, where he beat Jim Bailey in 3:47.3.

After these three great wins that put him high on the international scale, Delany returned home with a lot more confidence. He had achieved Olympic standards in both the 800 and 1,500, but selection for the Irish team was not forthcoming . A nasty spiking injury in Paris put him out of action for the whole of July. After only six days of training he was able to run a 4:06.4 Mile in London to prove his fitness. Then a poor run in Dublin led to the Irish press writing him off as an Olympic prospect. Delany returned to Villanova for the fall term still not knowing if he was going to the Olympics. It wasn’t until October that he found out from a newspaper that he was on the Irish Olympic team.

Olympic Triumph

|

| Olympic 1,500 Champion at 21. |

Delany had never given up hope of an Olympic berth, training hard throughout the American fall. “All the time,” Delany wrote, “Jumbo was drumming into my brain his particular philosophy on running to win [in the Olympics]. ‘There’s only one place to finish,’ he would say, ‘first. The rest are nobodies. It is not sufficient to run well…and perhaps take a place. If you want glory, if you want to go down in history, you must win.’ ” (p. 75) By the end of October his training results were better than ever and he felt “far fitter than when I had run my own four-minute effort the previous June.” (p. 76)

|

|

A rare photo of the 1,500 finish that shows Delany a few meters from victory. |

He arrived in Melbourne on November 19, just ten days before his 1,500 heat. He had not run a race since August, but he showed he was sharp by easily qualifying for the final: “I strolled home in third place,” he wrote later. (p. 80) For the final, Landy was still seen as the favorite, despite stories of an injury. There were three other four-minute milers in the final, Hewson, Tabori and Nielsen, all older than Delany, who of course had run 3:59. Delany was confident of winning and caught off guard had even told the British runners that he was going to win. But talking to the press he cleverly maintained a public image of uncertainty: “I am not certain of my condition. My best time since my injury last summer is 4:06. However, I feel I am running somewhat better than that.” (Track & Field News, December, 1956)

|

|

As his victory sinks in, he is hugged by John Landy. |

After a false start, the 1,500 finalists set off at four-minute-mile speed. As usual, Delany settled in at the rear of the field while Halberg and Lincoln did the leading (58.9, 2:00.3, and 2:46.6 at 1,100). By staying back, he was able to run relaxed (not jostling for position), to maintain an economic steady pace and to stay away from physical contact. At the bell, which in the excitement was not rung, the field was bunched over only 8m. Delany was on the inside with only Nielsen behind him, but he was still in touch. He moved up on the inside as they entered the penultimate bend and then got boxed in badly. Still looking more relaxed than any of his rivals, he had to drop back to get out of the box. At 300 he was in a position on the outside to make his move, but he was still 10th and 10m behind the leader Hewson.

Showing great confidence, he bided his time, moving up only one place and keeping an eye on Landy, who was ahead of him on the outside. He began his final effort just before the bend with 220m to go. By the crown of the bend he was passing Landy into fourth place and ready to pass Boyd and Richtzenhain, who were close behind the leader Hewson. Still in the Lane 2, he stormed into second place just before entering the final straight. By now, he had almost caught Hewson. The Englishman was able to resist for just a few meters; then the high-stepping Delany was on his own and going away. Track & Field News timed him at 12.9 for the last 100. Only Landy was able to match that kind of finish, but the Aussie favorite had left himself too much ground to make up. Delany’s last lap was timed at 53.8.

Indoor Quest

A 1,500 Olympic gold medal at the age of 21 after less than four years of serious running! When you reach the peak of the mountain, the only way ahead is downhill. That’s probably why Delany later wrote “The rest of my athletic career would always be a sort of an anticlimax.” Well, perhaps his amazing unbeaten streak of indoor wins over the next three years might be an anticlimax to the man or woman in the street, but it certainly wasn’t for indoor-track enthusiasts.

There was still much to keep Delany in the USA, although he had always planned to return home to Ireland. First was his commitment to Villanova and his coach. Second was the need to complete his degree. And third was the American indoor scene. He felt he owed a great debt to Villanova and to the indoor track scene for his gold medal: “There is no doubt in my mind that I would not have won an Olympic title if I had remained in Ireland. I benefited under the expert tuition of Jumbo Elliot. I learned tactical sense from my many skirmishes on the board tracks. And above all I competed against the best competition available week after week, year after year, in the US…. I am eternally grateful that I was afforded the opportunity of living in America and attending Villanova University.” (p. 86)

Rude Awakening

The 1,500 Olympic champion returned to Villanova a day late in January of 1957. His flight from Ireland had been postponed for 24 hours. This however was no excuse for the Dean of Disciplines, especially in view of the fact that he had been given a leave of absence for the Olympics. He was told he could not sit exams and thus would miss his scheduled graduation in 1958. Only an appeal to the President of the university saved him.

He nevertheless found time to race indoors four times in February, winning over a Mile each time and beating such milers as Seaman, Tabori, Dwyer and Beatty. Next he won two races for Villanova in the IC4A indoors meet, before returning to win three more Miles in open competition. He wasn’t going to lose a race until June 15. After his nine indoor wins he helped Villanova in outdoor competition racing 12 times in relays or individual races. On June 1 he won NC4A 880 and Mile titles (1:49.5 equaling his Irish record and 4:08.4). He achieved an even better 880/Mile double in the Houston Meet of Champions a week later, winning the Mile in 4:05.4 and the 880 in a PB 1:48.4 ahead of Olympic champion Tom Courtney—all in the space of 45 minutes. A week later he lost for the first time in 1957, finishing second to Don Bowden, 1:47.2 to 1:47.8 in the NCAA Championships. But this run was still a brilliant one, coming as it did just 20 minutes after he had won the Mile. Still, his 1:47.8 was yet another PB and helped Villanova win the NCAA team title.

Back Home for Holidays

|

|

Running behind Ibblotson, who was about to set a Mile WR of 3:57.2. Blagrove and Jungwirth lead. |

Then it was off to Ireland, where he beat Hewson and Pirie over a Mile just seven days after his NCAA race. Although he had been racing non-stop since the beginning of February, there was still a lot of pressure back home to keep racing. But Delany was “on holidays” after the rigors of studies and competition in the US: “We partied, we danced our feet off at tennis-club hops, went to the cinema and theatre and enjoyed any good spells of weather we got. On the other hand, I really had to run a lot of races in Dublin and Europe each summer I was home.” (147)

He raced because he felt an obligation to the Irish Athletic Association and to the Irish sporting public. After three low-key victories in Ireland, he went to London for the AAAs and won the 880 from Mike Rawson in 1:49.6. He was back in London a week later for an invitation Mile in which Derek Ibbotson broke the world record with 3:57.2. Delany ran a good race (3:58.8), but Ibbotson was too far ahead when he made his move 330 yards out. “Derek was in brilliant form that night,” Delany wrote, “and even though there was a suggestion at the time that I was boxed in by the Brits, there is no way I could have beaten him. I ran as hard as well as I could in trying to catch him.” (p. 167)

Back home, a tired Delany raced Ibbotson in a rematch ten days later, and although he was very tired by this time, he managed to beat the new world-record holder in 4:05.4. The Times reported that Delany “shot past” Ibbotson with 30 yards left, after he had trailed by as much as three yards in the last lap. (July 30, 1957) The 25,000 Irish crowd, according to Delany, were “deranged, distracted and almost dancing with hysterical delight” over their countryman’s great victory. (p. 168)

Senior Year

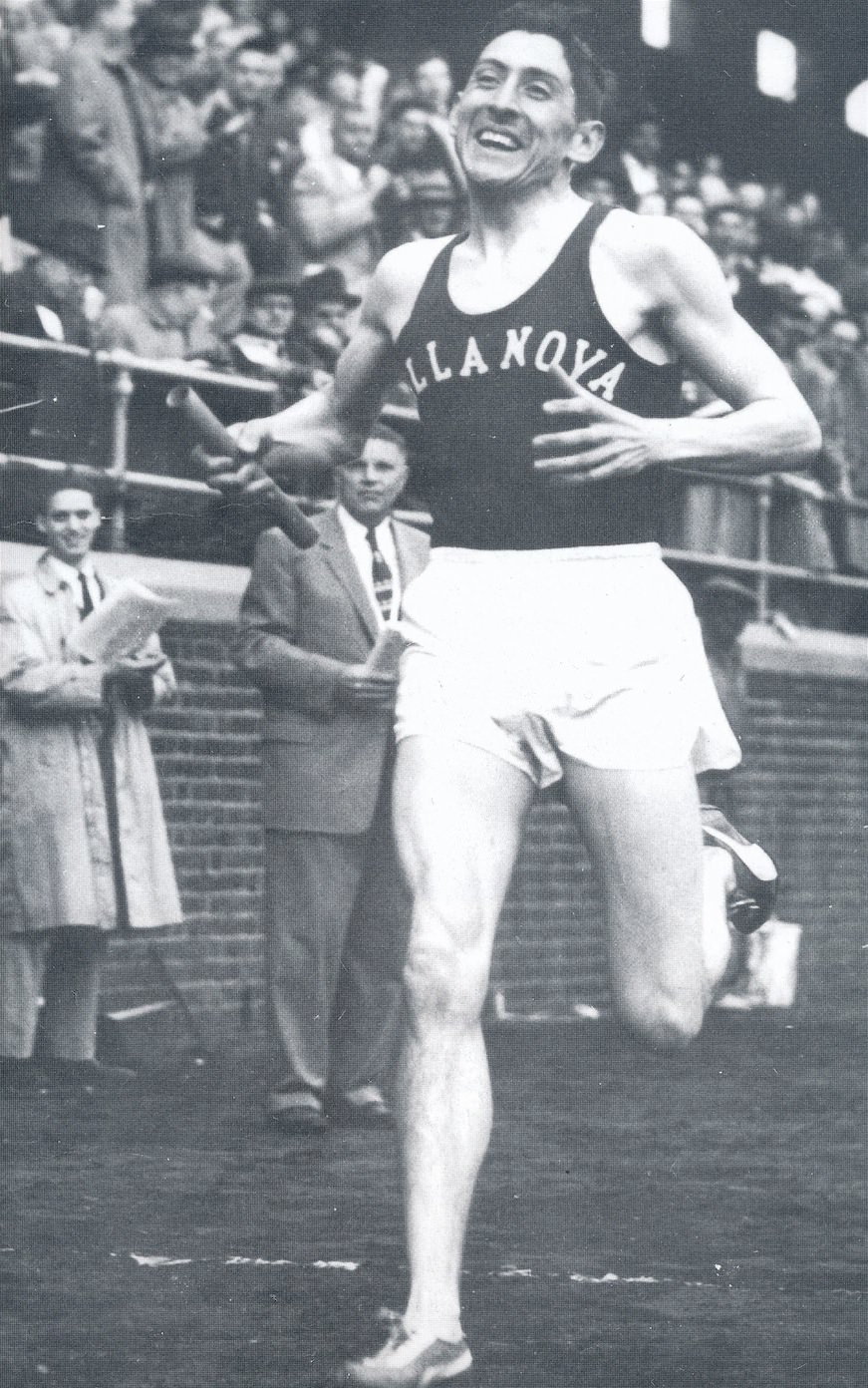

|

| The joy of winning for Villanova. |

Back at Villanova for his last year, Delany was spared from competing until the New Year. The mental break must have been most welcome. Not only had he experienced an unusually long season but he was also on line to defend his unbeaten record on the boards—now standing at 18 wins. Although he reveled in the indoor competition—“there was an intimacy about running indoors, of being so close to the spectators that [it] brought out the performer in you.” (p. 149)—he found his races by now to be increasingly stressful: “I can also clearly recall the gradual build-up of pressure and mental stress related to my successive victories. It was not so much the different athletes I had to compete against each week, but rather the psychological effect of having to continue to win, win, win.” (p. 153)

The media followed his winning streak continually as he increased it to 24 over January and February. Perhaps the competition was not as strong as in 1957, but his times were faster: 4:05.0, 4:08.1, 4:05.3, 4:04.6, 4:10.0, 4:03.7. The last of these was in the AAU Championships, where he not only beat the Hungarian Rozsavolgyi but also got within 0.1 of Nielsen’s world indoor record. After fulfilling his Villanova obligation with two wins in the NC4A, he added another four wins to his streak in March, finally achieving the world indoor record in Chicago with 4:03.4. But Delany was never really interested in records; he was always a racer first.

After stretching his unbeaten streak to 29, he underwent an intense period of outdoor racing, often in relays, for Villanova. He interrupted his university competition for a couple of races in Ireland to celebrate the opening of the new Santry track in Dublin. His competition there was the man who had beaten him in the Euros—Brian Hewson. In their two races, Hewson beat him over 880 in 1:49.7, while he won the Mile the next day with 4:07.5. Then back in the USA for his last hurrah on the track for Villanova, he led his team to an NC4A win with two victories: 880 in 1:50.0, Mile in 4:07.8. Two weeks later he won both the 880 (1:50.2) and Mile (4:03.5) within one hour in the NCAAs. Not surprisingly, in between these two championships he had a really bad Mile race in the Compton Invitational coming third in 4:10.0 behind Herb Elliott and Laszlo Tabori.

Summer 1958

|

1958 Santry Mile. Running fifth behind Thomas (38), Elliott, Lincoln and Halberg. |

His five-month American season was over, but when he went home for his “holidays,” there were another nine races waiting for him. He first ran a few low-key races in Dublin and on the continent, before he lined up for a big Mile at Santry Stadium on August 6. (See Great Races #12) Organizer Billy Morton had attracted a stellar field that included four great runners from Down Under: Albie Thomas, Merv Lincoln and Herb Elliott from Australia and Murray Halberg from New Zealand. The idea was to pit the local hero against some of the best in the world, and the concept caught on with the Irish public. Thousands were unable to get into the new Santry Stadium. All this of course put great pressure on Delany. Tired from the long American season and now supposedly on holidays, he would have preferred to take a rest.

|

|

Early stages of the European 1,500. Delany (120) hangs back while Waern leads. |

The race produced a stunning world record as Herb Elliott, paced by Thomas for over two laps, roared to a 3:54.5 clocking, 2.7 faster than Ibbotson’s mark. Delany found the pace of 56 and 1:58 frenetic: “It took my best effort to merely hang on. I was never to prove a threat. (p. 170) Only Lincoln managed to match Elliott’s third-lap surge. At the end, Lincoln was well clear in second (3:55.9) while Delany and Halberg fought it out for third place. Delany just managed to get third, with both he and Halberg clocked in at 3:57.5. It was a PB for Delany. He was graceful in defeat, calling Elliott phenomenal and saying that the only way to beat him was to tie his feet together.

After this race, Delany was “a sick as a parrot,” (p. 170) and his body ached for days after from the effort he had put in. Nevertheless, the next day Morton persuaded Delany to run an 880, which he dutifully won in 1:52.7.

|

|

1958 European 1,500 final. Hewson wins from Waern and Delany. |

The European championships were still to be run. A tired Delany went off to Stockholm to face Brian Hewson and Dan Waern in the 1,500. The pace in the final was steady 60s for the first three laps. At the bell Delany was in 11th place. He moved up to sixth on the back straight and collided with Hewson (“a hefty bump,” according to Hewson) as he tried to move up again. Hewson followed Delany round the last bend, the pair moving close to the leader Waern. At first it looked like Delany’s race, but in the last 50m Hewson roared though for a win, while Delany failed to catch Waern. 1. Hewson 3:41.9; 2. Waern 3:42.1; 3. Delany 3:42.3. Delany had run the fastest last lap (54.6), but he had left himself too much to do. He was running as a tired man: “My tactical running during the final was appalling…. It was most unusual for me to be so tactically careless…. I can only put it down to mental tiredness at the end of a long season…. I was at peak physical fitness but not mentally sharp to win on the day.” (p. 171-2) His season of 36 races was over.

Keeping the Streak Going

Wonderful though his ongoing unbeaten indoors streak was, it continued to put an inordinate pressure on him. During the indoor season, his winning streak was continually highlighted by the media. In one race he considered dropping out just to break it: “The thought occurred to me that I was sick and tired of having to bust my gut each weekend to win another race. I began to picture a scenario in my own mind of feigning a stitch in my side, stepping of the track and trying to explain to the media afterwards how I could not have continued to run because of the pain.” (p. 153)

|

|

Pushed by Rozsavolgyi, Delany sets a world indoor record of 4:01.4. |

But with the streak at 29, he returned to race the American 1959 indoor season. Although he had graduated, he returned to Villanova for a master’s degree, having earned a scholarship and permission to train once more under Jumbo Elliott. So he was in fine fettle when he lined up for his first race in Boston on January 17. Competing against the likes of Bill Dellinger, Phil Coleman, Dan Waern, Laszlo Tabori, Brian Hewson, and Istvan Roszavolgyi, he extended his winning streak to 40 by the end of March. Along the way he broke his own indoor Mile record with 4:01.4 with an effort that Joseph M Sheehan considered “still not all out.” (New York Times, Feb. 22, 1959) All but one of his eleven wins were over the Mile. He had just win over 880 when he beat Tom Murphy, Arnie Sowell and Mike Rawson. His streak of 40 wins was an incredible competitive achievement as well as being a feat of endurance.

Something had to give. And it soon did. It wasn’t the indomitable will of Delany; it was his body. After the indoor season he had decided to train but not race in the States until his studies were done. He started to run barefoot on the grass: “Running barefoot is as close as an athlete can get to an aesthetic experience…. It was a joyful expression of physical self-being.” (p. 174) Whether it was this new practice or whether it was the result of so many races in spikes on the boards, it is not known. But one day he seriously damaged his right achilles tendon during a speed session in spikes. He didn’t race again in 1959. Indeed, he didn’t race again until August 31, 1960.

And that was at the Olympics in Rome. After struggling for 17 months with achilles problems, Delany didn’t dare try out his damaged leg in competition before the Games. An unfit Delany did well in the circumstances, getting through the first round (1:51.0) only to be eliminated in the second (1:51.1). He had been selected for both the 800 and 1,500. But after this disappointing run, he scratched from the 1,500, thus giving up his chance to defend his Olympic title. “My preparations had been so precarious all along,” he wrote later. “I knew in my heart I was not fit enough to defend my Olympic 1,500 crown. It never occurred to me to consider running for a minor placing.” (p. 179) After the Games, there was one glimmer of hope: a close second-place finish (1:48.2) in Dublin behind the new 800 Olympic champion Peter Snell and ahead of Tony Blue and Herb Elliott. However, he never fully recovered from his injury.

Despite his chronic achilles tendonitis, Delany would not give up on his running career, even though his achilles tendonitis prevented him from running the 1961 indoor season. He was able to enjoy a reasonable outdoor track season in Europe, completing seven races and participating in a 4x880 relay. He focused on the 800 and managed first to earn second place behind George Kerr with 1:51.9. Then came his best run of the season. He didn’t win but he did set an Irish record with a fast 1:47.1, equivalent in time to his fine 1:47.8 clocking to win the NCAA title in 1957. In this race he was third behind the two best 800 runners at that time: Peter Snell and George Kerr, who had been gold and silver medalists in the Rome Olympics. Twelve days later he did finally manage to beat Kerr in Cardiff with 1:53.1. He finished the season with a win at the World University Championships in Sofia (1:51.1).

This win could have been a fine ending to his career, but Delany opted to stay in shape for the indoor season. His plan was not to try to extend his 40-race streak but to run for the Irish team that had set an outdoor European record for 4x800 the previous summer. He ran five relay legs in that 1962 season, but then his achilles went again. In the summer he announced his retirement.

Conclusion

Now, almost 60 years later, Ronnie Delany still keeps in touch with many of the finalists of the Melbourne 1,500: John Landy, Brian Hewson, Laszlo Tabori, Murray Halberg. Despite language barriers, he still sends Christmas cards to Klaus Richtzenhain. A charming and gregarious personality, he still enjoys contact with many of those who crossed his path during his running career. He has also written one of the best runner’s autobiographies, Staying the Distance.

His joy of competition benefited the sport worldwide and especially in the American college and indoor spheres. It is hard to convey in a short article how strongly he captured the interest of the public. His appeal was not only in his brilliant running but in his personality as well.

Although he was gifted physically, his competitive success came ultimately from his inner strength. First, he had the strength to perform well under pressure, to deal with the hurly-burly of top-level races. Second, this inner strength gave him the confidence to wait until the right moment to make his move. This enabled him to win big races. Third, he had the mental strength to compete so successfully so often. This kind of unremitting strength enabled him to achieve his 40-race winning streak in the American indoor circuit—a feat that will surely never be beaten.

Ronnie Delany is much more than an Olympic champion.

Note: All quotations from Ronnie Delany's Staying the Distance are indicated with just a page number.

8 Comments