Ron Hill Profile: Part One

1938-2021

(This is by far the longest profile I have written. I have tried to keep it brief, but there is so much material to cover. Much of the information here comes from Ron Hill’s wonderful autobiography The Long Hard Road, Part One and Part Two. Quotations from it are acknowledged by noting the part and the page (i.e., 1:222). I highly recommend Hill’s autobiography; it gives an honest, detailed account of all aspects of Hill’s life as a runner.)

|

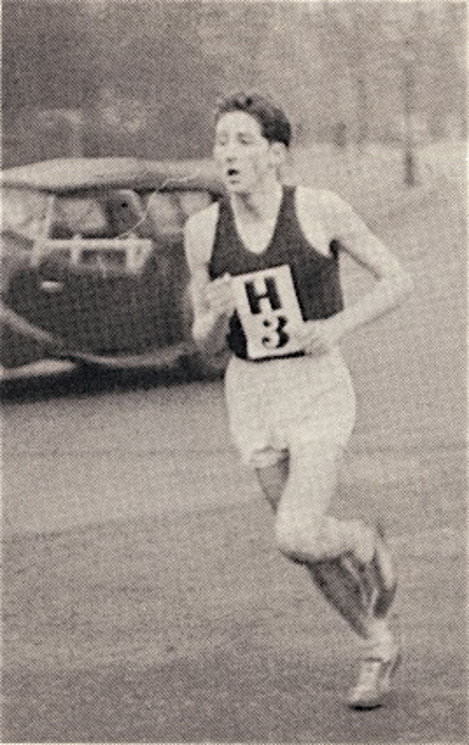

| On his way to victory inthe 1962 Inter-CountiesSIx Miles. |

In the history of distance running, few have challenged human physical limits more radically than Ron Hill. The 828 pages of his two books describe for us in rich detail the “trials and tribulations” he endured while trying to become the world’s best distance runner. After reading these pages, no one can question his courage, dedication and determination.

Some have questioned the harshness of his training and the frequency of his racing, but they often overlook that Hill is an extremely intelligent man who put a great deal of thought into his training and racing. At the same time he was a “hard” man who wanted to see how far he could push himself. As his career progressed, he came to realize that two recuperative periods a year were necessary. Once he learned how to avoid breaking down from his system of 13 training sessions a week, he became one of the best distance runners of the world. Indeed, he has rightly been called “an iconic figure in the distance-running world.” (Simon Turnbull, The Independent, 16 December 2007) Further, it is important to point out that during his career he always worked full-time.

In this first of a two-part profile, Hill is seen building up his mileage and sometimes breaking down through not taking any rest periods. His competitive record in road, cross-country and track reaches world class, but he disappoints in major championships. He has almost perfected his training practices, but he has exhausted himself in qualifying for those major meets. He has yet to perfect his preparation for winning a major championship.

Early Days

There was little to indicate that this frail English boy who grew up on a meager war and post-war diet, who was “useless” at cricket and football, and whose exercise was little more than walking to school and back, would evolve into a world-class athlete. Perhaps the only hint was Hill’s strong identification with Alf Tupper, a fictional hero from The Rover, a children’s comic weekly. Alf Tupper was known as “The Tough of the Track.” Hill was attracted to this tough character because he was from the north of England and because he worked on the railway like Hill’s dad. “Alf was always up against it,” Hill wrote later. “Whenever he had a big race coming up, something went wrong…. It used to bring a smile to my face to think of Alf walking away victoriously from the track, his holey vest, his tattered shorts and running shoes wrapped up in brown paper.” (1:8)

Even his surprising 9th place in a big schools cross-country race didn’t stimulate any interest in running. Rather he concentrated on his studies and joined the Boy Scouts. He was an active child and train spotting kept him busy. Soon after he was 15, his mother took him to see a friend of hers who ran for Clayton-le-Moor Harriers. He was soon running with the club, never winning any races but still placing in club events. He began running for his school as well. The next year he placed 42nd as Youth in the 1955 East Lancashire Cross-Country Championship. He then went on to place 116th and 226th in the Northern and Nationals.

|

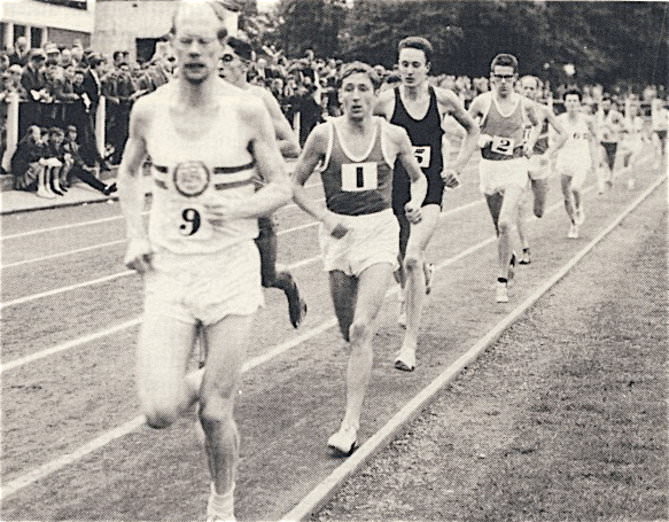

| 1958 Hyde Park Road Relay. |

His cross-country racing continued running through his schools years, while he studied hard to earn a place at Manchester University. On September 3, 1956, he started regular training and kept a log. On March 6, 1957 he won his first race. Earlier he had finished 57th in the Junior Northern Cross-Country Championships, but on arriving at Manchester University, he was only good enough for the second team.

His regular training, which soon evolved into a twice-a-day regimen, began to show results in the 1958 cross-country season. He was 14th in the Lancashire Senior, 33rd in the Northern Junior, and 108th in the National Junior. As well he became Manchester University cross-country champion. That summer he started doing interval training for the track season, which produced the modest times of 14:39.5 and 9:27 for Three and Two Miles. His weekly mileage increased too, from 40 to 70 by the end of 1958. His attitude to running at this time was still influenced by his comic hero Alf Tupper, the Tough of the Track: “To get ahead in running, you had to be tough.” (1:42) Throughout that winter, one of his “tough” practices was to carry out his training sessions in shorts.

Running as a Junior in the 1959 cross-country season, he posted promising but not outstanding results: E Lancs. 2nd, Northern 7th, Nationals 43rd. Perhaps his best run was 4th in the British Universities Championships. In the summer he dropped his Two Miles time by nine seconds to 9:18 and his Three Miles 19 seconds to 14:20.7. His improvement was not spectacular but it was consistent. Despite setbacks from illness and injury, his ambitious training regimen was showing results.

Life Changes

Then some big events in his life slowed his progress. In 1960 he lowered his mileage while preparing for his final exams. He got married that year too. Still he did manage to knock five seconds off his Three Miles PB. With the stability of marriage he settled into training 13 times every week. His dedication to this routine was evident when he took off only eight days after breaking his collar bone.

|

| Winning the 1961 Liverpool Marathon. |

His results were not great in the 1961 cross-country season, probably due to all the changes in his life. He was only 15th in the Lancs. senior after placing 14th the previous two years. And after coming 2nd in both the E Lancs. and Brit Universities, he was 81st in the Senior Nationals. Later there was improvement on the track: 7.5 seconds in the Two Miles (9:12.5) and 7.3 in the Three Miles (14:08.3) And for the first time he ran Six Miles. His promising time of 29:51.4 suggested that the longer track races were going to be his forte.

As well that year he ran his first Marathon, winning the Liverpool Marathon from John Tarrant in the impressive time of 2:24:22. Hill says that he entered the marathon because it was the only race that weekend. In his book Hill describes his post-race condition after he had been given a lift: “They had to practically carry me out of the car and prop me against the bus stop, my legs were so stiff and hurting. Never again. I had no intention of becoming a marathon runner.” (1:92)

Breakthrough

Over the 1961-2 winter, Hill’s appetite for running increased even more: “I became a fanatic for training and racing,” he wrote (1:100). He was up to 90 miles a week in the fall, often training with miler John Whetton. And in the 1962 cross-country season he showed dramatic improvement for the first time: 2nd in the Lancs., 7th in the Inter-Counties, 1st in the E Lancs, 1st in the British Universities and 7th in the Nationals.

|

| Chased by Eddie Strong in the 1962 Nationals. |

His 7th in the National Cross-Country gained him a place on the England team for the Internationals, where he finished a creditable 11th. Just before that race he had amazed himself with a huge 21.9-second Three Miles PB of 13:47.4 indoors at Wembley. Not surprisingly, Ron Hill was on a high: “I felt I could run forever and could take any races going.” (1:118)

So after many years of gradual improvement, Hill suddenly had a big breakthrough in 1962 at the age of 23. Why was this? Much of the answer can be found in 1960, the year he graduated from University and the year he got married. With his final exams out of the way and a Courtaulds research fellowship helping to pay the bills, his life became more stable: “One thing that married life brought me was a steady routine…. Training was regular, thirteen times a week.” (1:72) He had already been training twice a day since 1958, but his stable life enabled him to increase his mileage to 90 a week. His sudden improvement was accentuated by two relatively lean years competitively (1960 and 1961) when he was adapting to his new life. But 1961 saw his most consistent training so far. And it should be noted that in the winter of 1961-2 Hill did a lot of interval training with Mile specialist John Whetton; this surely did a lot to improve his basic speed.

Reality Check

Hill still believed he could “run forever” without taking any long breaks. It wasn’t until the autumn of 1962 that the continual training-and-racing regime started to slow him. For most of the summer he continued to run really well. A week after his international debut, he won the Longwood 10 in 51:47. The next weekend he ran another indoor Three Miles in 13:47.0, just a PB. In May he ran 11 races in 21 days. These culminated in his first 20-mile race, the Pembroke 20, which he won in a course record 1:42:23. He then had a big breakthrough to win the Lancashire Six Miles in 28:18.2, a PB by 93.2 seconds. This victory led to his first race at the White City in the Inter-Counties Six Miles. Unfortunately he was now past his peak: he placed 9th in a slow 29:24.2. “I was thoroughly cheesed off and disappointed,” he recalled. (1:123)

Reality set in after this race; he was very tired and finally gave himself an easy week, “the first time I’d eased up in months.” (1:124) Now up to international standard, Hill looked at the race calendar to see where he might represent his country again. The Marathon! So he entered the famous Poly Marathon, perhaps inspired by marathoner Jim Peters’ book In the Long Run that he had recently purchased and read twice. “I knew that a win here in a good time would get me selected for the European Games…in September and maybe the Commonwealth Games…later in the year.” (1:124) With his fine 1:42:23 in the Pembroke 20, his expectations were good. Maybe he would be a marathon runner after all.

In the 1962 Poly Marathon, he was up with the leaders from the start: “I had no pre-race plan…. I wanted to get some miles out of the way, with minimum effort, before the real race began.” (1:126) Feeling good at six miles, he took the lead. Only John Tarrant went with him. Tarrant stayed with him until 12 miles. Once on his own, Hill began to tire. He says he had four or five “really bad patches” (1:128), but he managed to hold on to win in 2:21:59, with a 1:22 margin over Mihalic of Yugoslavia. This PB earned him his second national vest. But it came at a cost.

Need for Rest Periods

|

| Competing in Europe. |

Hill tried to ignore this fatigue, continuing to put in 90 miles a week and to race. Finally his body gave in: sore legs, chronic stomach aches, sore throat, stiff neck, aching bones. He finally rested for five days and then trained only once a day for three weeks. After pushing himself to his limit, often running through illness and injuries, Hill was moving towards the realization that he needed two rest periods a year for optimum improvement and performance. Such a huge effort by someone who had not really trained for the marathon finally burst the bubble of amazing form that Hill had experienced in 1962. His body was no longer capable of another major effort. In the European Marathon in Belgrade, he was able to stay with the leaders for the first 10K, but then he was dropped: “I felt tired in my legs…. It was like being in a nightmare, the field was moving further and further away, and I was struggling to run even downhill!” (1:37) He finally dropped out at 30k, completely spent. In his diary he found lots of reasons for his bad run, but the root of his problem was fatigue from a long season and from his hard Poly Marathon.

“Wot No Shoes!”

There had been another innovation in the Hill running strategy in 1962: barefoot running. Following Percy Cerutty’s back-to-nature approach in Australia, which included a lot of barefoot running on sand dunes, several top English runners had begun to train and compete barefoot. Bruce Tulloh, Frank Salvat and Jim Hogan were the first ones. Then Ron Hill began to race barefoot: “I had started barefoot racing probably for two reasons. Firstly it fitted the image of the sort of athlete I wanted to be, a hard man, able to run without shoes, and secondly it was much easier to run, provided the ground was not slippery, because of reduced or no weight on the feet.” (1:132) For a few years, Hill raced regularly in bare feet on cinder tracks. He even ran some cross-country races barefoot.

Back to Form

After recovering from the fatigue of the long 1962 season, he ran well in the 1963 cross-country season: Lancashire 1st, Inter-Counties 9th, Northern 2nd, Nationals 15th. He still continued racing a lot, and managed a three Miles PB of 13:41.2 just before he defended his Poly Marathon title.

|

| On his way to a Six Miles win against the USA. Heatley leads. |

The Poly had more competition this time: American Buddy Edelen, Alastair Wood and Juan Taylor. Although he ran well and lowered his PB by 3:53 (2:18:06), he could not stay with Edelen, who won in 2:14:28, a World Best by 48 seconds. Next, he concentrated on the track. A 3,000 victory in Zurich showed he had some good track speed, so he was confident of success in the AAA Six Miles. His main competition came from Edelen, Basil Heatley, Jim Hogan and Gerry North. The race soon developed into a barefoot duel as Hill and Hogan pattered away from the field. Despite using regular surges over the last six laps, Hill wasn’t able to drop Hogan until the last lap. His winning time was 27:49.8, which equaled the Commonwealth and National records. This was by far the best track run of Hill’s career so far and ranked him third in the world with his time adapted to 10,000.

The rest of the track season saw him win an international race against the USA (27:56.0), run a PB 13:29.8 Three Miles, and finish third in the 5,000 at the World University Games in Brazil. Such a positive track season found him training keenly for the Olympic Games in Tokyo the next year. He wanted to run both the 10,000 and the Marathon. Hill put in a good fall of training (90 a week) while working on his Ph.D. thesis. This hard work led to one of his best cross-country seasons in 1964: Lancs. 1st, Intercounties 4th, Northern 1st, Nationals 3rd, International 2nd. By the spring he was up to 100 miles a week.

Chasing Olympic Selection

He took a “rest” in April while finishing his thesis; this meant his mileage dropped to 70-80. But in May he was back to full training and lined up for the Intercounties Six Miles in the hope of impressing the Olympic selectors. It was a stellar field with three barefoot runners (Tulloh, Hogan and Hill) as well as Heatley, Batty, Bullivant and Hyman. The 89-degree heat meant there were no fast times. Hill won by 2.2 seconds from Hyman in 28:26.8. His track speed (27.4 last 220) was impressive. Next he showed the selectors that he had strength too—with a world best 20 Miles victory at Pembroke (1:40:55) ahead of Kilby and Heatley.

This bode well for the Poly Marathon, which would strongly influence Olympic selection. And Hill’s confidence was evident from the start as he led through 5 miles (25:10) and 10 Miles (50:20). He then eased up as he was tired of leading, allowing the chase pack to close up. Just before 20 miles a marshall failed to make Hill turn left. When he was finally back on course, he found Heatley had a 10-yard lead. He caught Heatley and at one time had a ten-yard lead on him, but Heatley was stronger at the end and took him just before entering the stadium. Both ran brilliant times: Heatley’s 2:13:55 was the fastest marathon ever; Hill’s 2:14:12 was also inside Edelen’s world best and gave him a 3:54 PB. Had Hill run as steadily as Heatley and had he stayed on course, he might well have been a lot faster. Still, he had almost certainly made the Olympic team.

|

Now he had to do well in the AAA Six Miles to qualify for the Olympic 10,000. With his Ph.D. completed, Dr. Hill lined up at the White City with the same opponents he had faced in the Intercounties, minus Tulloh and plus Mike Freary. The pace was fast: 4:30 at one mile and 13:42 at three. Hogan continued to do most of the leading. With three laps to go Freary roared into the lead with Hill on his heels. But he only lasted half a lap and left Hill to go it alone for 2 1/2 laps. He could hear someone behind him, but it wasn’t until the end of the race that he learned it was Mike Bullivant. Despite a huge effort on the last lap, Hill was pipped at the line 27:26.6 to 27:27.0. Both had broken the European record. Now assured of an Olympic 10,000 place, Hill followed up with two international 10,000 victories against Finland and France. Then came the news that he was on the Olympic team for both the 10,000 and Marathon. He had achieved his goal for 1964, but had the effort been too much?

First Olympics

Except for a “rest” in April (70 to 80 miles a week), he had been going hard for eleven months. Now he had six weeks before the Games. He averaged 105 miles a week in September and felt in form. And his training in Tokyo went according to plan. He decided at the last moment to wear spikes, although his two fine Sixes had been run barefoot. The race was a nightmare: “I ran like a drain…. My legs had no response at all, almost as if I were petrified…. The last few laps were murder.” 1:237-8) He was 18th in 29:53 and was lapped by the first four runners.

The Olympic Marathon was six days later. He started well: 4th at 5K and 10th at 10K. Just before halfway, his two team-mates, Heatley and Kilby, went by. Over the next 5K he lost several more places, but then managed to stabilize his position. It was a huge effort to hold on for 19th place (2:25:34.4). Despite all the dedicated preparation, Hill’s first Olympics had been a huge disappointment.

Bouncing Back

|

| Peter Keeling helps Hill to world records for 15 Miles and 25K. |

It didn’t take Hill long to get over this setback. After a break, his mileage was up to 90 in November. He was ready to perform well in the 1965 cross-country season: 5th in the Intercounties, first in the Northern, 5th in Nationals and 7th in the International. This was not quite as good as 1964, but it showed he had recovered. A PB in the AAA 10 Miles (48:56) showed he was ready for a good track season. The big test was the AAA Six Miles. As well as the Olympic silver medalist Gammoudi, his old rivals Hogan, Bullivant and Freary were in the field. The race was very tactical, with Gammoudi often moving to the lead and then slowing the pace. When Hogan and Gammoudi made a move with three laps left, Hill was caught napping. He shadowed Bullivant, who made up the gap, and then sprinted from the bell. He was able to catch Hogan, but not Gammoudi. Still, his 27:40.8 was an excellent time considering the erratic pace of the race and the muddy, windy conditions.

Hill now focused on Zatopek’s 15 Miles and 25K world records. In front of 3,000 spectators in Bolton, Peter Keeling and Roy Williams took him and Mike Freary through two miles in 9:21. A lap later, Hill and Freary took over, each doing two laps of leading at a time. They passed six miles in 28:41.6 and ran side-by-side through ten miles in 48:11.4, a PB for Hill. Freary was aiming for times at one hour and 20K, after which he dropped out, leaving Hill alone. It was painful running, but he got the 15 Miles WR by 72.8 seconds with 72:48.2. He had two more laps to run for the 25K mark and another WR of 75:22.6. This was 73.8 seconds faster than Zatopek’s record.

After this brilliant run, Hill’s wife May was hospitalized. Although he kept running and racing, his focus was altered. His mileage was erratic, and he failed to finish a 30K race. It was only the fourth time in his life that he had not finished a race. Once May had recovered in the fall, he was back to full regular training. In fact he was about to have his most successful cross-country season so far.

National Cross-Country Title

|

| Outsprinting Mike Turner for the 1966 English Cross-Country Title. |

After winning the Lancashire title, he was second to Roy Fowler in the Intercounties. Now up to 105 a week, he was getting stronger. A disappointing second in the Northern lowered his aim in the Nationals to a place on the national team; he had no intention of running to win. After a poor starting position that left him 30th in the early stages, he soon managed to get up with the leading bunch. Mike Turner, who had beaten Hill in the Northern, soon made a break. Hill bided his time with Fowler and Lachie Stewart. Then after four miles, he left his two companions and caught Turner. The two ran together until a hill half a mile from the finish. At this point the two swapped leads several times. With 100 to go Turner had a 3-yard lead, but Hill came again and won with a sprinter’s dip-finish. A superb race. But after this, his International sixth place disappointed him.

Clearly he needed a rest. Realising that in the past he had not taken a proper spring break after a hard winter’s training and racing, he drastically reduced his training for a whole month: two weeks of 2-mile runs, a week of 2- and 5-mile runs and a week of 7-mile runs. Then the focus was the two big Six Miles (Intercounties and AAA) and the Poly Marathon. The Intercounties Six Miles was an exciting race with four together at the front with 880 to go. When Tulloh made a move, Hill and Rushmer fell trying to stay in contact. Both got up again and chased Tulloh and Hogan. Tulloh held on for victory, while both Hill and Rushmer caught Hogan near the tape to dead-heat for second (28:10.2).

Major Games

Hill’s effort in this race was likely the cause of a chest infection just before the Poly Marathon. Although he never looked like winning, he did achieve his goal of finishing in the top three and thus qualify for the Euros. Then he ran his best time in the AAA Six Miles. In the field were two international stars, Gammoudi of Tunisia and Mecser of Hungary. Also likely to challenge were Alder, Rushmer and Tulloh. He was running in spikes for a change, and this caused him problems after three miles. He had stayed with the leaders up to that point, but then his left foot became numb. But he held on and the front runners came back to him. After passing Rushmer, he was with the four leaders at the bell. His last lap of 60.5 earned him fifth and a new PB: 27:26.0. He never ran faster.

With his good performances on the track and road. Hill earned a place on both the Commonwealth and European teams. But as in Tokyo two years earlier, he was disappointed with his Six Miles race in Jamaica. He was not pleased with his fifth place, especially since he was lapped by the winner Naftali Temu. His time of 28:42.6 was 27.2 slower that Jim Alder’s time for third. He was even more unhappy with his 12th place in the European Marathon (2:26:04.8). This time he was affected by a bad stomach upset mid-race. Again, he had worked hard to qualify for major games only to disappoint. Clearly, the effort to qualify had put him over the top. But the 27-year-old wasn’t defeated: “The latest downfall made me even more determined one day to succeed.” (1:311)

1967: A Consolidation Year

After a four-week “rest” similar to the one early in 1966, Hill began to build up his mileage. By December it was up to 95. He had another busy cross-country season, his best run coming in the Intercounties (2nd), while he won the Lancashire and Northern. With an 11th in the Nationals, he just made the England team and was 11th in the International. In the AAA 10 Miles he ran a PB, winning in 47:38.6. Next came a victory in the Intercounties 20 with the fast time of 1:40:49. After another “rest” for four weeks in May, he ran a PB Three Miles in July with 13:27.2, before running second in the Enschede Marathon (2:23:43.6). A tour of South Africa completed his relatively low-key year, after which, with thoughts of the 1968 Olympics he put in the miles and raced less often. His average week was now around 120.

Olympic Build-up

|

| On his way to winning the 1968 English cross-country title. |

This consistent training bore fruit in the 1968 cross-country season. He was unbeaten until the International, where his old nemesis Gammoudi pushed him into second with a 1.4 second victory. Previously he had won the Lancashire, the Northern, the Intercounties and the Nationals (his second National title). “I felt now I could get a medal in the Olympic marathon,” he wrote (1:368). And his brilliant form continued in the AAA 10 Miles with a WR victory in 47:02.2. Still maintaining his mileage, he ran a World Best in the Pembroke 20 (1:36:28).

After his now regular active rest in May, Hill was back at the White City in July for the AAA Six Miles. His fourth-place time of 27:30.6 pleased him as he had a chest infection. But his main focus was the upcoming Olympic trial for the Marathon. Although recovered from his infection, he was unable to qualify in the top three, finishing fourth in 2:17:11, his second best time. This meant selection for the 10,000, not for the Marathon, in the UK Olympic team.

Mexico 10,000

|

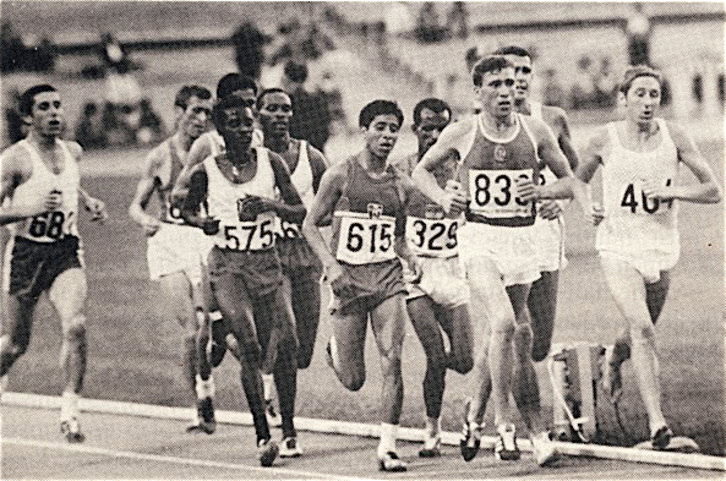

| Olympic 10,000: In the lead with five laps to go. |

Prior to the Games he showed good track form running close to his best for Two Miles (8:42.8) and winning a 10,000 race against Poland (29:17.8). Then his pre-race training in Mexico went well. With the altitude in mind, he decided on a very conservative approach: “run it easily, steady pace, and from the back.” (1:396) The mass start was the usual chaos, forcing Hill, in bare feet, to run off the track to avoid two fallen runners. After this he was running dead last.

He ran two 75 laps, then two 74s, as he gradually moved through the field. He increased to 73s and 72s. By halfway, he had passed team-mates Tagg and Hogan and was 15th. With 3,000 to go he had caught the large leading bunch and lay 12th. Running at 71 pace, he moved up to 8th. As the leading group had dropped four runners, he didn’t want the pace to slow, so he took the lead with 5 1/2 laps to go. No one had expected that.

With four to go, he moved out and let the field by. Then Keino dropped out, leaving Hill in 7th place. But when the pace picked up with three laps to go, Hill couldn’t respond. However, he did hold on to seventh (29:53.2), one place behind Ron Clarke. It was an amazing performance when considering he was beaten by three altitude natives, a runner who had lived three years at altitude and two runners who had spent several months at altitude. Hill himself had spent just 19 days at altitude. He now felt confident that he had developed the right training program and looked ahead to major games in 1969, 1970 and 1972.

End of part one

4 Comments