Bayi v Liquori v Coghlan

1975 Dream Mile

International Freedom Games

Kingston, Jamaica. May 17, 1975

Great Races #23

Kingston, the venue for the 1975 Freedom Games, produced a capacity 36,000 crowd to see not only a version of the Dream Mile but also a sprint contest between Steve Williams and Houston McTear. While the sprint races were predominantly an American affair, the Dream Mile had a far greater international flavour. True, there were four Americans in the field, but there were also an African, a Brit, an Irishman and a Jamaican. It was an impressive field.

Before the Race

|

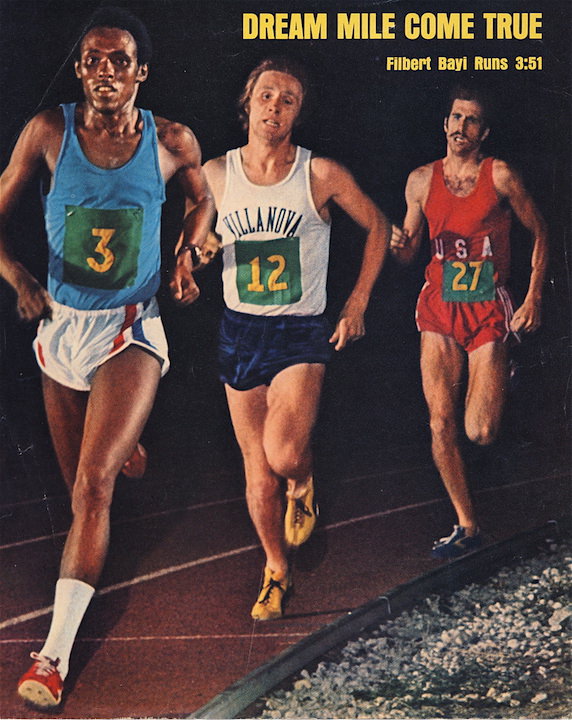

| The Sports Illustrated cover showing Bayi leading Coghlan and Liquori. |

The big name was Filbert Bayi (21), the current world-record-holder for the 1,500. Bayi had flown in from his native Tanzania 48 hours before. Earlier in the month he had raced and won twice in Italy over 1,000 (2:18.1) and 800 (1:48.3). Bayi’s reputation was high, especially after his epic victory over John Walker at the 1974 Commonwealth Games in a WR time of 3:32.16. He was facing two runners from Villanova University who had been making news in the USA. Marty Liquori (25) had been good enough to beat Jim Ryun back in 1971 and boasted a PB of 3:53.6; Irishman Eamonn Coghlan (21) was just emerging as a world-class runner and had run 3:56.2 two weeks earlier. Both were coached by the legendary Jumbo Elliott at Villanova University.

A wildcard in this race was the speedy Rick Wohlhuter, the 880 WR holder with 1:44.1, the fastest over 800 in 1974 (1:43.4), and a promising 1,500 runner with 3:39.7. There was a third WR holder in the race: American Tony Waldrop, who owned the indoor WR for the Mile (3:55.0). Waldrop had run nine consecutive sub-4’s in 1974 and had a best outdoor Mile time of 3:53.2. Rounding out the field were Walter Wilkinson of Britain (3:56.6), Brian McAfee, a sub-4 runner from North Carolina, and Sylvan Barrett of Jamaica.

Expectations were high for a fast race, but that was mainly up to Filbert Bayi, who had a reputation as a front runner. The Tanzanian was cagey about his tactics: “I don’t known whether I will lead or not. I know they would like me to go ahead, but I don’t know yet what tactics I will use.” (Sports Illustrated, 26 May 1975) His main rivals, Coghlan and Liquori were both kickers so were unlikely to push the pace early on. Coghlan himself badly wanted someone else to make the pace: “So far this season, in any race I’ve run, I’ve been out there myself in the lead, and I haven’t been pulled right from the start.” (Sports Illustrated, 26 May 1975) Another unlikely pacemaker was 800-runner Rick Wohlhuter, who was somewhat of a novice at this longer distance. Tony Waldrop, with his 3:53.2, had a good chance of winning so would not want to sacrifice himself for the sake of a fast race.

There was a lot of excitement in the air as the runners were introduced to the Jamaican crowd in considerable detail. Surprisingly, the biggest roar was not the announcement for their own Sylvan Barrett but for the announcement of Filbert Bayi: “This mahn runs his races like a mahn who has stolen the mangoes and is running from the police.” (On the Run, Marty Liquori and Skip Myslenski, p. 186) This colorful intro proved to be a perfect description of the way Bayi was going to run!

The Race

As it turned out, there was no need for a pacemaker. Bayi, starting on the inside, used his 1:45 800m speed to claim the lead round the first bend. He was challenged at first by Coghlan and Wilkinson, but he was the one who most wanted the lead. Along the back straight he built up a six-yard lead, but then eased a little. His first 220 was only about 29, by which time he had a four-yard lead.

Bayi really turned it on round the second bend and entered the straight with a much bigger lead (12yds). No one was interested in going with him. At 330, Coghlan decided that Wilkinson, in second place, was letting the Tanzanian get too far ahead; he moved ahead an upped the pace of the field. At 440 in 56.9 Bayi was still 12 yards and 2.0 seconds up, and he stretch it at least to 15 yards round the next bend. Coghlan was clearly worried, and entering the back straight, he accelerated and moved away from the field. Liquori, back in fourth, quickly moved up to third when he saw Coghlan opening up a gap. Coming off the bend at 750, he had almost caught his Villanova colleague. Bayi, meanwhile had eased somewhat, so that at 880, Coghlan (1:58.0) and Liquori (1:58.4) had significantly closed the gap to about 10 yards.

Coghlan continued to do all the chasing, while Liquori seemed to be just hanging on a few yards behind him. By 1100, Coghlan had almost caught Bayi; it must have been a huge effort. Liquori was barely in contact. Coming into the straight before the bell, Coghlan was with Bayi and Liquori had almost joined them. It was on this straight that Bayi was challenged for the lead as Coghlan moved up on the inside and drew level. Liquori had dropped a little, just out of contact. But Bayi, fleeing like a mango thief, escaped contact with a quick burst, passing 1320 in 2:55.3 with Coghlan (2:55.7) and Liquori (2:56.2) in his wake. It was definitely a three-man race at this point.

Coghlan was almost able to hold him round the bend, but Bayi slowly began to move away as the three entered the back straight for the last time. At this point Liquori moved up to Coghlan’s shoulder. The two inadvertently bumped at this point as Coghlan resisted Liquori’s challenge. Coghlan’s battle with Liquori led to him catching Bayi with 220 to go. But yet again Bayi responded to the challenge and open up a gap of round the last bend. At the crown of the bend, Liquori finally passed the tiring Irishman and tried to close the 4-yard gap to Bayi. But this gap didn’t close; in fact it widened in the last 40 yards. So Bayi had a 1.2-second lead at the tape and a second world record to go with his 1,500 record: 3:51.0.

After the Race

Bayi’s mark was just 0.1 of a second inside Jim Ryun’s WR that had stood since 1967, almost eight years previously. Now Bayi had both the Mile and the metric Mile WRs, having run 3:32.2 in the Commonwealth Games 16 months earlier. His 3:51.0 Mile was all the more amazing for two reasons. First, he regularly ran unnecessarily wide round the bends, thus covering several extra yards during the four laps. Second, although his lap times of 56.9, 59.7, 58.7 and 55.7 appear reasonably consistent, he nevertheless sped up and slowed down several times. Had he run close to the kerb and at a more consistent pace, he would surely have been under 3:50. He seemed in control the whole race and was able to take the kick out of his two main rivals with classic catch-me-if-you-can front-runner tactics. And he still had to run a world-record time to win the race.

Liquori not only ran a PB with 3:52.2 but also claimed the fifth fastest-ever Mile time. He said that he wasn’t disappointed: “This is the first time I’ve really trained for a race since this meet two years ago. It makes a difference when you have a goal. I have to admit I was nervous today and that’s not much fun, but sometimes you have to do it. It’s scary, though. I really don’t know if Bayi was even ready for this race.” (On the Run, p.187) Liquori ran a shrewd race: he was careful not to expend too much energy in the early stages. But perhaps he should have been ahead of Coghlan at the bell if he was going to beat Bayi. He relied a little to much on the younger Coghlan to keep Bayi within striking distance; at one point in the third lap, he yelled at Coghlan to overtake Bayi. Furthermore, he left himself too much to do in the last 200, where he not only had to make up ground on Bayi but also had to pass Coghlan on the crown of the last bend. By the time he hit the straight, Liquori admitted, “My legs were just dead.” (Sports Illustrated, 26 May 1975) To be fair, he did try to pass Coghlan on the back straight; maybe the bump with the Irishman was just enough of a setback to deprive him of a chance of winning.

Eamonn Coghlan was “little-known” (Times, May 18,1975) outside of the USA at this time. He was a star at Villanova University, but still inexperienced on the international level (Seventh in his 5,000 heat with 14:29.6 at the 1974 European Championships). Thus his third place in a PB of 3:53.3 was a huge breakthrough. With a previous best of 3:56.2 set just a week earlier, Coghlan was courageous to take up Bayi’s challenge; in fact, he was the only one in the race to do so. Not surprisingly, he was suffering on the last lap: “For three quarters I felt great, really within myself. The last lap, though, took quite a bit out of me. As soon as I caught Bayi the second time he took off again, and when Marty passed me, I lost my confidence a bit…. But it was a great race and I’m really delighted I was part of it.” (On the Run, p.187). To add to Coghlan’s delight was an Irish and European Mile Record. The European record that he had broken was Michel Jazy’s 3:53.6, which had been a WR in 1965.

Behind the top three, Rick Wohlhuter was fourth in a 3:53.7 PB, a really fine run that was overshadowed by the record breakers in front of him. The half-miler said despairingly afterwards, “The Mile will be the death of me. I keep running better times and getting lower places.” (Sports Illustrated, 26 May 1975) In fifth was Tony Waldrop (3:57.7), who must have been disappointed he didn’t PB like those ahead of him. Also under 4:00 was sixth-place finisher McAfee with 3:59.5.

2 Comments