RALPH DOUBELL PROFILE

b. 1945

Perfection is an overused word, but few would disagree that on October 15, 1968, Ralph Doubell achieved perfection in Mexico City. The 23-year-old Australian not only ran a tactically perfect 800 race but also won an Olympic gold medal in a world-record time. This perfect race was the product of five years of intensive training under the coaching of Franz Stampfl. During this period, Doubell was either a full-time student or a full-time employee.

In his most successful years from 1965 to 1970, Doubell was Australian 800 champion five times. He won the World Student Games 800 in 1967 and was an 800 finalist in both the 1966 and 1970 Commonwealth Games. And in addition to his outdoor 800 WR (1:44.3), he set two indoor WRs: 1:47.9 for 880 and 2:05.5 for 1,000 yards. As well, he won many indoor races in the USA, taking six of six in 1968.

Early Days

|

Like many great runners, he had an active childhood. Growing up in Melbourne, he developed strength and stamina early: “I was a paper boy and pushed a pushbike five or six miles each day. I had a whole load of papers sitting on the crossbar in a sugar bag.”

His early sporting interests focused on cricket and football. “My greatest desire was to play cricket for Australia,” he recalls. But in his last high-school year he came in contact with Mike Agostini, the 1954 Empire Games gold medalist for 100 Yards. Agostini saw Doubell had sprinting potential. “[His] interest gave me an important boost and a focus on what to do.” Doubell later told Brian Lenton. (Brian Lenton Interviews, p.39) Under Agostini, he went on to win the 440 and 880 in the Victoria Combined High Schools Championships.

In 1963 Doubell enrolled at Melbourne University, where famed running coach Franz Stampfl worked. Doubell, however, was not yet committed to running, although during his first year he did compete in the Australian University Championships in the 440 individual and relay events. It was only after hearing about the travel potential offered by the sport that he approached Stampfl: “I told coach Franz Stampfl that I wanted to run 50 seconds for the quarter and train three times a week. Franz peered at me through his monocle and very matter-of-factly said, ‘I will tell you how much and how often you train.’” (Lenton, p.39)

Franz Stampfl

Not everyone was able to deal with Stampfl’s strong personality: “He was dictatorial; he was adamant in his views,” Doubell told Amanda Smith of Sports Factor (Radio Broadcast, 28 July 2000). He waxed lyrical on Stampfl in his interview with Brian Lenton: “Did he have a strong personality? Was he eccentric? He had both characteristics and he was certainly forthright…. You never devised a training session—he did! And you would be foolish to question him; the training load would be doubled.” (Lenton, p. 42) Doubell had the strength of character to be able work with such a forceful personality: “There was never any real conflict,” he says. “I accepted what he said. He’d done it before, so I had absolute faith in him. He delivered, and I delivered. At the end of the day it was an equal relationship.” Soon Doubell was training much more often than three times a week as he gradually settled into Stampfl’s interval training routine. (See box)

| Doubell's Winter Training (outlined in Athletics: The Australian Way)(Converted to metric) Morning: 6-8K jog Evening:5K Warm-upM 50x100 [40 brisk walk]T 10x1200 [880]W 20x300 [not given]Th 10x600 [not given]F RestSat 30x200 [not given]Sun 20x400 [not given] Doubell started by doing about half of the above.As competitive season approached, volume was halved and speed was increased.Timetrials over 200,300,400 and 600 (for speed).Mileage 19-25K a day. |

One of the difficulties with Stampfl’s system was the need to grind out repetitions on the track day after day. And Doubell did all his training on a cinder track unless rain prevented access. He has stated that Stampfl’s personality helped his athletes carry out the workload: “He had the ability to inspire, to motivate me to do the extra 20% of training, which you had to do, and come back the next day and do it again.” (Amanda Smith) Doubell found that the group spirit of Stampfl’s runners also helped him to get through the grind of track training: “I trained with a group of people who helped me enormously but didn’t have the same success. I certainly couldn’t have done [it] without them. Many people would see repetition after repetition at Melbourne University as very boring, and sometimes it was. But we had a fine group of people who would swap stories and work experiences…. You always had that spirit of camaraderie and cooperation.” (Lenton, p. 46)

Another difficulty with Stampfl’s system was the danger of injury from the wear and tear of continual track training. Stampfl adopted no strategies to avoid injury: “He would normally ignore any complaints about soreness or injury,” Doubell recalled. “We just kept running. We toughed out the injuries.” (Amanda Smith) Once Stampfl told Brian Lenton that Doubell was prone to injury, but Doubell denies this: “There were some periods where I had, say, a strained achilles, but if you are training at that level you are going to have some injuries. I don’t think I ever missed any major events because of injury although I was hampered at times especially if running on an uneven cinder track.” (Lenton, p.41)

|

|

Many hours of discussion with Coach Stampfl. |

Doubell progressed steadily under Stampfl’s coaching as he built up the training workload. Initially Stampfl worked on his running style, but “after the first year he was comfortable with it.” Doubell has always generously emphasized Stampfl’s role in his success. In a eulogy at Stampfl’s funeral he said, “I would have to say I owe my gold medal for the 800 meters in the 1968 Olympics to Franz’s coaching and guidance.” (Lenton, p. 42)

Unlike many coaches, Stampfl spent a great deal of time with his athletes away from the training track. “Quite often on a Friday we would go down to lunch on Lygon Street in Carlton,” Doubell recalled. “We’d be first there at lunch, but last to leave. Then we’d go to Jimmy Watson’s wine bar. So between 12 and 4 I had an earful of Stampfl, but by the end of it I could normally believe that I could beat anybody in the world.” (Amanda Smith) Stampfl famously wrote that “the coach’s job is 20% technical and 80% inspirational” (Franz Stampfl on Running, p.146) and that a coach’s job involved being a “guide, philosopher and friend, counselor and confessor, a prop at times of mental tension.” (Stampfl, p.151)

Progress

|

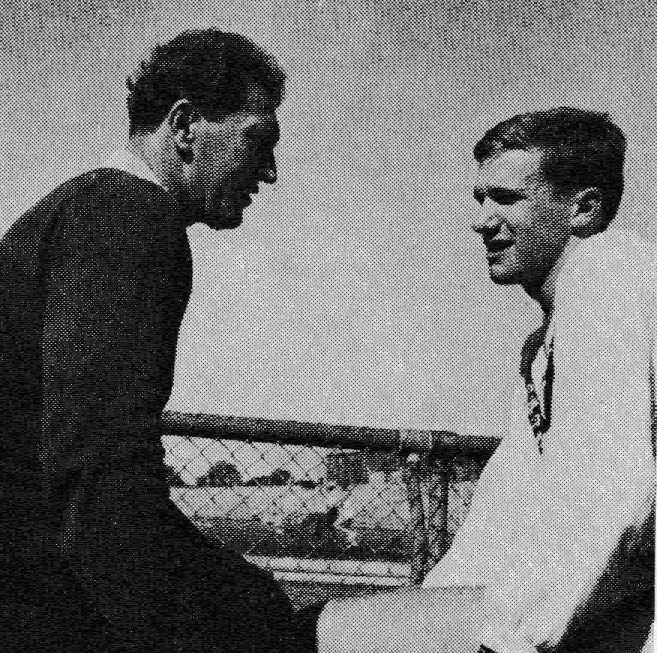

| "I thought I could beat Ryun." Clough, right, gives the 880 world-record-holder a goodrace over 880 in Los Angeles. |

The first indication that Stampfl’s training system was working came in an early time-trial, when the 18-year-old Doubell ran 1:54.8. Asked by Brian Lenton if there was one early race that indicated he had real potential, Doubell said it was the Victorian 800 championship in 1963: “The race favorite was Stan Spittle…. Stan was one of the best half-milers in the country and yet I won quite easily. Everything came together in that race. It was just six months after starting serious training.” (Lenton, p.40)

Early in 1964 Doubell ran a respectable fourth in the 880 in the Australian Championships with 1:52.9. The next year he was Australian champion with 1:50.6. He was to win this title in 1966, 1967, 1969, and 1970. His win in 1966, this time over 800, (1:47.3) led to his selection for the Australian team for the 1966 Commonwealth Games in Jamaica. He was also chosen for the Mile.

But before those games, he represented Australia at 880 in an invitational meet in Los Angeles, California. This was an important race in his development into a world-beater. He was up against he great American miler Jim Ryun, who had set an 880 WR of 1:44.9 earlier in the year. No one expected Doubell to offer challenge, but such was his competitive attitude, he still ran to win. And the pace was fast. He was second behind Ryun at 660 (1:19.0), running much faster than he had even run before—1:45.3 pace. Although he faded in the straight, he held on for fourth, to finish only a second behind Ryun at the end, 1:46.2 to 1:47.2. “Everyone was running for second except me” he remembered. “I thought I could beat Ryun even though he was the Mile record-holder. That race taught me that too many athletes are intimidated by reputations. I came close enough [to Ryun] to realize I could mix it with [him] over his non-specialist distance. It certainly gave me confidence to keep working at it.” (Lenton, pp. 40-1)

Adversities

|

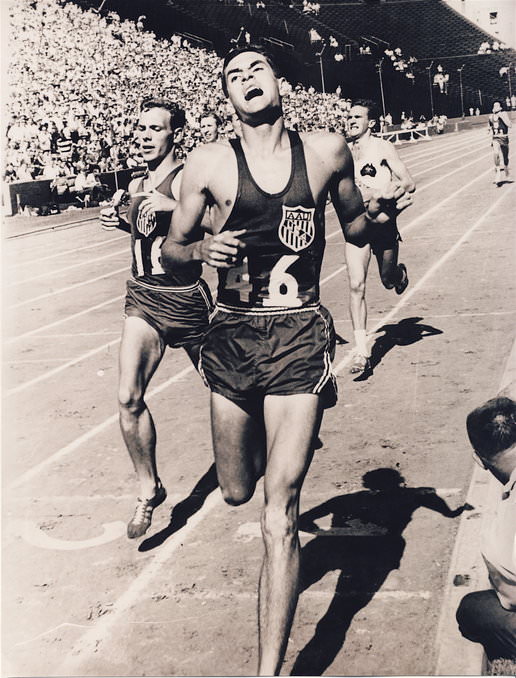

| Out in front: one of Doubell'smany indoor races in America. |

Unfortunately Doubell contracted tonsillitis in LA. This forced him to compete sick in his first major games, the 1966 Commonwealth Games. In the 880 he was third in his heat (1:55.9) and first in his semi-final (1:48.3). The final was very fast, the first lap being run in 49.6, and Doubell was up there in fourth (50.8). But as Kerr and Kiprugut battled for first position, the ailing Doubell dropped back. Meanwhile, his older team-mate Noel Clough, whom he had beaten for the Australian title, was running the race of his life and went from last at the bell to win the race with a big 1.4-second PB in 1:46.9. Doubell was sixth (1:48.3). In the Mile he was second in his heat (4:04.0), but his illness forced him to drop out of the final after being up with the leaders in the early stages. On returning home, he went straight to hospital.

In the following 1966-1967 Australian season, Doubell did not run as well as he had hoped. He focused his domestic season on beating the current Commonwealth Champion Noel Clough, which he achieved in the Nationals. He also toured North America to compete indoors, a practice that continued through to 1972. “It was as much a travel exercise as it was to get good class competition,” Doubell explains. Still, Stampfl was supportive of these tours. Did they help Doubell develop tactical skills? “To an extent. Indoors you need to have very strong acceleration because you don’t have the long straights.”

Major Victory

The following September after his initial indoor-racing experience, Doubell won his first big outdoor meet, the 1967 World Student Games in Tokyo. At the time he was angry at being omitted from the Commonwealth team that had faced the USA the previous month. He felt he was “very fit” just before the World Student Games, having run a fast 660 in 74.7. (Aitken, More Than Winning, p.87) The 800 final was “brimful of talent” (Times, Sept. 4, 1967) and included American Wade Bell, who had won in the recent Commonwealth v USA meet (1:45.0), the 1,500 winner Bodo Tummler, and European record-holder Franz-Josef Kemper.

Tummler led from Kemper after 200 and passed the bell in a slow 54.4. Tummler and Kemper were still in the lead going into the last bend, with Doubell third and Bell fourth. At the crown of the bend, Kemper burst ahead and looked to have the race won. But Doubell quickly passed Tummler and chased after Kemper. Neil Allen described the final moments of this exciting race: “Twenty yards from the tape [Doubell]drew level with the German, who weaved to the right at that moment, clashed elbows with the Australian, and both almost broke stride. Then they recovered and Kemper, with Doubell just two feet in front, made two more despairing attacks before the line was reached in 1:46.7 by Doubell.” (Times, Sept. 4, 1967) This was his finest run so far, for he beat some of the best 800 runners in the world with a time that ranked him tenth in the world.

Olympic Selection Worries

For the last three months of 1967 Doubell, who had now graduated from University, was working away from home in Sydney. This change adversely affected his training. Nevertheless, in his second American indoor season early in 1968, he won six of six races. But he admits he didn’t have much training background behind him for these races. (Aitken, p.87) And the break in his training routine put him under pressure to qualify for the Mexico Olympic team. He ran only 1:49.3 behind American Preston Davis in the Nationals. Fortunately he had another chance at the qualifying time four days later: “I managed 1:47.2, mainly because I rested those four days and I had completely recovered, and I knew it was all or nothing for me.” (Aitken, p.87) This 1:47.2 clocking qualified him for Mexico. “Ralph was very lucky to be picked,” Stampfl recalled. “Even his friends doubted whether he would survive even a heat…. I was convinced that he could in fact win an Olympic title.” (Amanda Smith)

The skeptics looked like they might be right, for after running a slowish 1:47.9 in April, Doubell had no competition at all before the Olympics in October. But the lack of competition didn’t worry him: “I’m not a great believer that racing is necessary to give you that edge. Maybe in sprinting it does. But I felt I could train as well for the 800 without competition as with competition.” (Lenton, p.46)

This was just as well because Doubell wouldn’t have been able to compete anyway. Although his preliminary conditioning for the October Olympics went well, he began to have some achilles pain at the end of July. This forced him to cut back on his speed work. At least he was still able to work hard with swimming and weight training. At one point he had to stop running for two weeks, and for the last four weeks before going to Mexico, he was getting treatment twice a day. He told Alastair Aitken how a couple of time-trials helped boost his confidence: “I could not run in spikes for the last six weeks before I left for the Games, except the day before we left [in] a time trial over 440 yards in 49.9. It felt very easy. The week prior to that I ran a three-quarter-mile time trial in warm-up shoes in 3:01.8, so we thought we had everything worked out okay, but we were fortunate it had clicked.” (Aitken, p.89) Despite some swelling during the trip, his achilles gave him no problems once he was in Mexico.

Mexico Olympics: Getting Ready

Of course, a big issue in Mexico City was the 2,240m altitude. “We went out with the approach that it wasn’t going to affect the 800, and that proved to be the case,” Doubell explained. (Athletics NSW, 1993) But another important issue was the effect of altitude on day-to-day recovery between the heats, semi and final. This remained an unknown. Doubell had four weeks in Mexico City before his races. And he did undergo some physiological tests which showed he wasn’t “particularly affected by altitude.” (Lenton, p.40) Doubell has explained his general attitude towards the altitude issue: “You can have two effects: one is physical, the other is psychological, and a lot of athletes were defeated by the psychological effect—they just couldn’t handle the threat.” (Lenton, p.40) Doubell himself had come to terms with the psychological effect. This helped him significantly when the actual competition began.

Another issue that had to be dealt with was his racing speed, especially since he had not been able to train in spikes for several months back in Australia. But this issue didn’t worry him. “You can build up speed quite quickly,” Doubell claims. And during his the four weeks in Mexico before the competition, he worked successfully on his speed. One series of 10x300, which was timed by a French journalist, was “very, very fast.”

Stampfl arrived in Mexico just a few days before the competition began. He believed his job had already been done; now it was up to his athlete. According to Doubell, he gave very little instruction: “Before I raced in Mexico, there was a single stern instruction: Go out and win the next three races.” (Lenton, p.42) Still, Stampfl’s presence in Mexico was a great boost to Doubell: “At times the relationship was almost psychic. In a race I could feel his thinking about what I should do next, when to make my move.” (Lenton, p.42)

Heat and Semi-Final

After resting three days—“normally I would not run two days before a major race”--Doubell won the first of his “next three races,” Heat 4 of the 800. Since this was his first race for six months, the time was respectable: 1:47.2. It was a good morale booster. But his temperament was tested when a runner from El Salvador cut him off badly near the start and caused him to stumble. Stampfl later said that Doubell told him it was “the hardest raced he’d ever run.” (Amanda Smith)

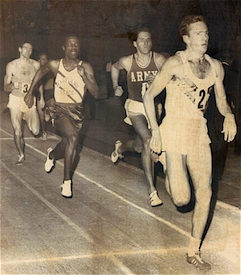

His semi-final was more important as he was up against the clear favorite for the gold medal: Wilson Kiprugut, who boasted two Commonwealth silver medals and the best 800 time of the year. Doubell wanted to make a statement in this race. He knew that the Kenyan would go off fast, so he planned to start steadily and then move up to Kiprugut for a final sprint. Kirprugut did indeed start fast and passed the bell in 51.3 with a 10-meter lead.

Doubell waited until the start of the last bend before making his effort. He recalls how easy it was moving up from fourth to third and then to second. Coming into the straight he decided to test his rival and moved level with 60 to go. “This was the start of the psychological battle. I drew level, and glanced across and indicated that I thought this seemed like an ordinary training run…. I then breezed by to win by one or two meters.” (Speech at Melbourne High School, 1996. Quoted by Harry Gordon, 2004). Doubell had now ensured that Kiprugut would run even more scared at the front in the final. As a bonus, his winning time of 1:45.7 was achieved with relative ease.

Olympic Gold

The final was to be his third race in three days, but he could not afford to worry about the unknown effect of the altitude on his consecutive racing days. Of course, there were other runners apart from Kiprugut to worry about: Czech Josef Plachy had been only 1/10th behind Kiprugut in the semi and Tom Farrell of the USA, who was only another 2/10ths back. Germans Adams and Fromm had looked good in the other semi with 1:46.4 and 1:46.5.

|

| Frame from the race film after 16 seconds: Kiprugut (left) has alreadybuilt up a huge lead on Doubell (right). |

After the eight runners finally lined up, there was a false start. Doubell was wrongly blamed, but he had the presence of mind not to let the injustice faze him: “If I break [now], I’ll probably be disqualified,” he thought. “Better take it easy.” (Lenton, p.49) So he was in last place round the first bend. But there was another good reason for him being in last place: most of the field had set off at breakneck speed. Within 16 seconds Kiprugut was 10 meters ahead of Doubell. The Kenyan had already used up valuable energy, while Doubell was running a more even pace.

|

| Just past the bell. Doubell (one from right)is in the second lane but well positioned toreact to Kiprugut (in lead). |

Kiprugut passed 200 in 24.0. Doubell, who had moved up a little on the latter part of the back straight, was about one second behind. Ever watchful of Kiprugut, he was fifth coming round the second bend almost in lane 2. When the field bunched at the bell (51.0) he was sixth and quite close to the lead. This was fine: he was on the outside of the field and in no danger of being boxed. He had run the first 400 in almost even 25 and 26 splits, whereas Kiprugut had expended more energy in running uneven splits of 24 and 27. As Doubell said later, “The critical part of the race was the first lap.”

He had to run in lane two round some of the third bend to keep free to match any move by Kiprugut. This was just as well, as Cayenne in second place began to fade and with 300 to go Kiprugut suddenly moved away from the field. Doubell had to react. He recalls: “That was one of the most critical moves in the race. Cayenne was dropping back; Kiprugut was going further out. Fromm realized it and he went up. I followed Fromm. But then Kiprugut seemed to be getting further out. I needed to make sure that the rubber band between him and me stayed taut, so I moved up [past Fromm] to within 2-3 meters.”

|

| 200 to go: Doubell has Kiprugut wherehe wants him. |

Doubell had made this crucial move with apparent ease. His crisp upright running style showed no signs of stress or fatigue. Kiprugut’s attempt to break away had failed. After passing Fromm in the middle of the back straight, Doubell had the Kenyan where he wanted him, one meter ahead. But he needed to be patient: “There was a temptation to take him on at that stage. I was probably hesitating for the next 50-80. But then I really needed to leave it until the top of the straight before kicking. Because at that speed--it felt pretty fast--I couldn’t risk running out of puff.” Doubell did indeed follow his race plan. And around the final curve he did let Kiprugut open up a three-to-four meter gap, which became large enough for the BBC commentator to predict that Kiprugut was going to win. Was Doubell that confident that he could let Kiprugut increase his lead at this late stage? “Yes. I was still in contact with him, and he didn’t break the elastic band.”

|

| Last bend: Doubell lets the elastic band stretch. |

From the crown of the bend, Doubell began to close the gap; he was on the Kenyan’s shoulder as they hit the straight. “When I caught Kip in the last turn,” he said after the race, “I knew nothing could stop me from winning.” (Track and Field News, Oct/Nov 1968) Five meters behind them, Fromm, Plachy, Farrell and Adams were shoulder-to-shoulder fighting for third. Keeping his form, Doubell went into his sprint mode; however, Kiprugut still had something left and was able to resist. But with 50 to go Doubell was ahead. He described this stage of the race as “that magic moment when the race was decided, [when] physical and psychological contact was broken.” (Melbourne High School lecture) He held his form to the tape, while Kiprugut was desperately flailing his arms in an attempt to to get more speed out of his legs. Doubell had equaled the WR with 1:44.3 and Kiprugut was only 0.2 behind him with a 1:44.5 PB.

Race Assessment

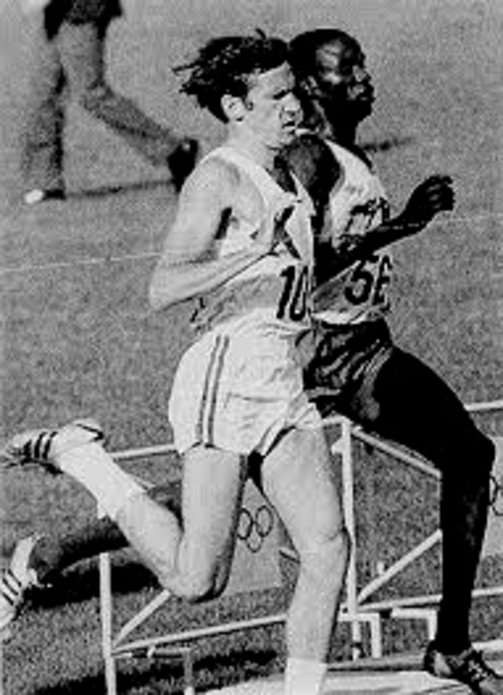

|

| Doubell about to "breeze by" Kiprugutin the semi-final. |

At a dinner after the Games, Roger Bannister, who had run the first 4-minute Mile under Stampfl’s coaching, called Doubell’s win “a perfectly judged race.” Doubell has stressed that for the race itself he was on his own: “It ultimately comes down to the athlete taking over the responsibility for the tactics and the race. Franz didn’t have anything to say before the final.” On the start line, Doubell had a precise idea on how his race was to unfold—in a way that anticipated the later technique of visualization: “I think it’s important that an athlete in a final has his mind absolutely clear on how he’s going to win that race. There shouldn’t be any confusion; there shouldn’t be any third-party input. The athlete has to decide how to win the race.” In saying this, Doubell was in no way indicating that Stampfl didn’t contribute to his victory; he was stressing that in the actual race, the athlete must be in total control. Of course, Stampfl’s considerable input came earlier. Indeed, Doubell has said that he owes his gold medal to Stampfl’s “coaching and guidance.” (Lenton, p. 44)

After Mexico

How do you follow up on the ultimate achievement of an Olympic Gold medal in a world-record time? You either retire, as Herb Elliott did, or you keep going for a repeat in the next Olympics four years later. Doubell, at age 23, decided to go for the latter, much more challenging option.

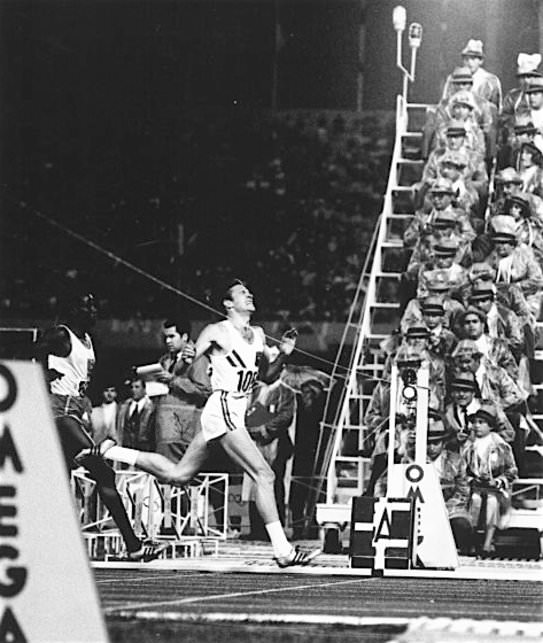

|

| Doubell hits the tape. Kiprugut (right) has conceded the goldmedal. Behind them Farrell (271) gets third ahead of Adams (2) and Plachy (22). |

Following his gold medal, it was indoor competition in North America that nourished his motivation. After his unbeaten indoor series in 1968, Doubell went on to set two WRs in the next two seasons of competition. In setting these two WRs, he showed that he could also run well from the front. In 1969 he set a WR 800 mark with 1:47.9, leading the whole race. The next year he broke the 1,000 yards WR (Peter Snell, 2:06.0) with 2:05.5, taking the lead at 600 and winning by 25 yards. Both these WRs were run at altitude in Albuquerque, New Mexico, which meant that all three of Doubell’s WRs were achieved at altitude. But he doesn’t see any significance in this fact: “I don’t think there is anything that can be read into it.”

Through his success on the North-American circuit, Doubell became a sports celebrity. One newspaper tagged him “Ralph the Rapscallion.” Sports Illustrated made fun of the media attention: “People, guys who get paid to be reporters, keep asking Ralph Doubell the darndest questions. Win one lousy gold medal and right away you go from obscurity to a fish bowl where even the color of your undershorts is no longer sacred. Like the guy in New York a few weeks ago who demanded to know why Doubell drank French champagne instead of Kentucky bourbon. And what else could Doubell do but say that if anyone happened to have any bourbon, he’d be happy to swallow some, say a fifth?” (SI, February 23, 1970)

Outdoors Doubell was not so successful. In 1969 he won the Australian 800 title again and ran a reasonable 1:46.8 in Milan. The next year, he was again Australian champion—but for the last time. And then in the 1970 Commonwealth Games in Scotland he was a disappointing sixth in the final, a full second behind winner Robert Ouko. Bob Phillips reported that Doubell “simply did not have the legs to match the pace of the 21-year-old Kenyan. (Honour of Empire, p.116). Doubell himself admits that “the fire in the belly had gone.” Still, he continued to work towards his Olympic goal through 1971 and into 1972. The end of his quest came in an indoor race in Toronto, Canada, when he pulled a calf muscle. With this injury he retired. It was only six months before the summer Olympics.

Life After Running

As soon as he retired from serious running, Doubell enrolled at Harvard for an MBA. He then worked for Citibank for 13 years, specializing in lending and working in New York, San Francisco, Melbourne and London. Goldman Sachs was his next employer. He began in London and New York and then opened a Goldman Sachs branch in Sydney. After eight years, he moved to Deutsche Bank, where he worked from 1991-1999. Currently the 67-year-old is Managing Director of a Canadian company, Artez, that develops software for fundraising.

Retrospect

|

| Mexico victory. |

Looking back more than 40 years, can Doubell point to anything he should have done differently? “I was successful, so why change it? I would not change anything.” He believes it was an advantage to have been either a full-time student or worker throughout his running career: “It’s critical you have a balance—so you are not doing athletics all the time. You’ve got to have something else.” Also, he was fortunate to be working with Franz Stampfl, with whom he developed “almost a father-son relationship”: “You need a very strong coach; you need to have absolute faith in that coach, which I did.” With good basic speed—he believed a successful 800 runner should be a good 400 runner with strength—Doubell worked hard on the track to develop his stamina. With the help of Howard Toyne, one of the first sports-medicine doctors in Australia, he was able to withstand the grueling interval sessions prescribed by Stampfl. But above all, Doubell’s personal qualities of dedication, intelligence and strength of character were essential for his success.

5 Comments