1964 Olympic Games

Tokyo, October 10-24

800

There was much speculation over the fitness and intentions of the current 800 WR holder and Olympic champion Peter Snell. Unlike his rivals, he had not raced in Europe over the summer. Further, he had run only 1:48.5 in the earlier New Zealand summer. He told the press that the 1,500 was his main goal, so some doubted whether he would run the 800. And Snell was giving nothing away as to his fitness or his plans. In fact he was not sure himself about the 800. He had trained incredibly hard over the New Zealand winter, at one stage averaging 100 miles a week over a 10-week period. This distance training was followed by a sharpening period. But this was all done in the New Zealand winter, so he was unable to run any fast time trials. Any concern over his 800 speed was eradicated soon after his arrival in Tokyo when he ran a 1:47.1 time-trial. This convinced him that he could do both the 800 and 1,500.

|

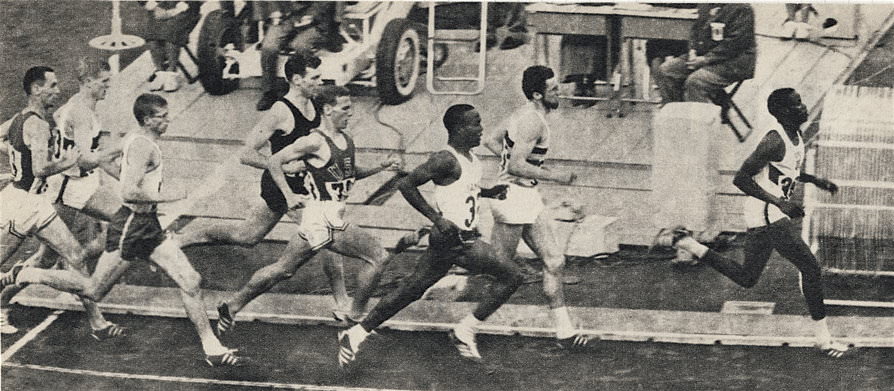

| Kiprugut leads at the bell. from Pennewaert, Kerr, Farrell,a boxed-in Snell, Crothers, Bogatzki and Siebert. |

There were several 800 runners capable of challenging Snell. Of particular concern to him were two old Commonwealth rivals, Bill Crothers of Canada and George Kerr of Jamaica. While these two reached the final, other prospects were eliminated in the first round: American Morgan Groth, the fastest 800 runner of the year; Neville Myton of Jamaica, who had run so well several months earlier; and Noel Carroll of Ireland. The semis, won by Snell, Kerr and Crothers, showed that the three favorites were in fine form. Also impressive was Wilson Kiprugut, who ran an Olympic record (1:46.1) behind Kerr in the second semi; Kiprugut was virtually unknown, and his listed PB of 1:48.0 did not appear in any official race results.

It was Kiprugut who led the tightly packed field at 200 (24.9) and at 400 (52.0). At this point Snell was boxed in. He had to run as wide as lane 4 to get into a decent position at the start of the back straight: “I felt I was capable of dropping back out of the box, going round the field and still being able to challenge.” (No Bugles, No Drums, 185) Then with 250 to go he escaped from the field within 50 meters with a stunning acceleration that only Kerr could respond to at all. The rest of the field were now fighting for second place. At 600 Snell was alone (1:19.4), while behind him Kerr led Kiprugut and Crothers.

|

| Snell leads on the last bend from Kerr andKiprugut. Crothers (57) looks the most relaxed. |

Despite putting in two big efforts in the third 200, Snell kept clear to the tape, drawing on the strength from his endurance training. He clocked his and the world’s second-best time of 1:45.1. Crothers, going into the last bend, showed that he had good acceleration too, taking over second place from Kerr. With 100 to go, Kiprugut made his effort, but it was interrupted when he almost fell after clipping Kerr’s foot. Amazingly he recovered quickly enough to still catch Kerr before the tape and win the bronze behind Crothers. Crothers had run a fine last 200 and was only half a second behind the apparently invincible Snell. The Canadian’s time made him the second fastest man ever over 800.

The first four were in a class of their own. Behind them American Tom Farrell ran a PB to get fifth, while his American colleague Jerry Siebert, who was running with a fever and great pain, was a courageous sixth.

1. Peter Snell NZL 1:45.1; 2. Bill Crothers CAN 1:45.6; 3. Wilson Kiprugut KEN 1:45.9; 4. George Kerr JAM 1:45.9; 5. Tom Farrell USA 1:46.6; 6. Jerry Siebert USA 1:47.0.

1,500

Peter Snell’s strength from distance running was crucial to his task of winning this race as well as the 800. After three rounds in the 800, he faced three more over 1,500. But this was the least of his concerns. His team-mate John Davies was in fine form. “John was going extremely well and I was finding it a struggle to keep up with him,” Snell wrote later. “I couldn’t help thinking that, if form in training was what counted, John was going to clean up the 1,500.” (No Bugles, 174) Also, likely to be a threat were two Europeans: Josef Odlozil of Czechoslovakia and Witold Baran of Poland. Then there was the always tough Alan Simpson of Great Britain and Dyrol Burleson of the USA.

|

| Snell makes his break. Just past the crown of the top bend, Simpson(159) is trying to move up, ahead of him are Davies and Baran and Odlozil (84) . |

Two early victims in the heats were Valentin of Germany and Olavi Salonen of Finland. The semis, with the first four qualifying plus the fastest loser, were exciting. In the first one, all five qualifiers were under 3:40. Snell looked in control, although winning by only 0.1 seconds in 3:38.1. The second semi was incredibly close with the first six finishing within 0.4 of a second. Keino of Kenya and Allonsius of Belgium were the unlucky ones, although they finished in the same time as the third and fourth finishers.

In the final, the pace remained steady at 60-second speed for the first three laps. Michel Bernard led for 500. John Whetton led to 600 and then Davies, who wanted a faster pace, took over. Davies had to abandon his plan to make a run for the tape with 500 to go. But all he did was maintain the 60-second-per-lap pace until just past 1200. No one wanted to push the pace; in fact, they all played into the hands of the 800 champion.

Snell waited till the end of the back straight to take the lead. Track and Field News gave some useful stats: the pace of the race was 14.5 per 100m until this point. Then Snell ran a 12.7 to gain the lead and followed this with a 12.3 round the curve. By this time the race for gold was over, and he cruised in with a 13.6 final 100m. “If anything, my run down the straight was a little bit easier than it had been in the 800 metres,” he said. (Bugles, p. 190) He had a 1.5 second lead at the tape. Head-on photos of him finishing underline his total dominance of the rest of the field.

|

| Snell's domination shows in this photo.Odlozil (left) will come through for secondahead of Davies. |

The race for second was a thriller. When Snell made his move on the back straight, no one else could answer. In his wake, Davies led the chase group into the last bend, followed by Baran. Simpson, running really wide, moved into second coming into the straight. But this effort was just a little too much for him, and he began to fade. Baran looked likely to get second, but Odlozil was moving fast on the outside. Meanwhile, Davies moved up between Simpson and Baran. It was a desperate three-man race for second. Odlozil was the one find something extra and just passed Simpson and Davies for second. Simpson dived flat out to hold off Davies, but his valiant effort was in vain. Burleson was able to pass Baran for fifth. Less than a second separated second and sixth.

1. Peter Snell NZL 3:38.1; 2. Josef Odlozil CZE 3:39.6; 3. John Davies NZL 3:39.6; 4. Alan Simpson GBR 3:39.7; 5. Dyrol Burleson USA 3:40.0; 6. Witold Baran POL 3:40.3.

5,000

Several runners lined up with realistic hopes of gold. Frenchman Michel Jazy, moving up from 1,500, hoped to improve on his silver medal in Rome. He clearly had the finish to win a slow race, but he had not proven himself in a fast race over this distance, his best being 13:50. Though not as fast a finisher, Ron Clarke of Australia was looking to make up for the disappointment over 10,000 four days earlier. With a three-mile time equivalent to about 13:39, he had to be considered a gold prospect. Bob Schul (26) of the USA had beaten Clarke over 2 Miles indoors and had clocked a fast13:38 in Compton to defeat New Zealander Bill Baillie, another medal contender in this race. He also had two four-minute miles under his belt and a 2 Miles WR of 8:26.4. Schul had won the US trials comfortably from Bill Dellinger (29); Dellinger had decided not to peak for these trials—a risk, he said (See Kenny Moore, Bowerman, p.174), but he wanted to peak in Tokyo. Also in the field was Briton Mike Wiggs, who had impressed after running at a US university. Harald Norpoth (22) of Germany, with a 13:48.4 PB, was yet another medal prospect. He had made the European 1,500 final in 1962 and was with the leaders when he fell with a lap to go.

The race began in steady rain. The sodden track at least had no puddles. The first two laps were slow, 68.8 and 69.7. Then Clarke took over as expected. Passing 1,000 in 2:50.2, he ran laps of 64.7, 67.2 and 68.5, to pass 2,000 in 5: 39.4. Next Clarke made his strongest surge, spreading out the field considerably. His sixth lap was 62.5. However, perhaps through lack of confidence, he eased up with a 70.6 lap and allowed the field to regain contact. He surged again with a 65.7 lap, passing 3,000 in 8:22.2. Jazy was right on his shoulder and Norpoth and Baillie close behind. Schul and Dellinger, who had run at a more even pace moved up with the leaders as Clarke slowed with a 69.3 lap. The Aussie tried to surge again, but with little authority, and Jazy surprisingly and perhaps unwillingly took over the lead. A 67.9 lap. The lead group still had nine runners with 600 to go. A surprise runner in this group was a young Kip Keino of Kenya, whose best time was equivalent to only 14:15.

|

| A desperate Jazy leads round the final curve as Schul (719)and Norpoth (209) have him in their sights. |

At this point Dellinger rushed from the back of the pack to take the lead. He headed the field as they passed the bell in 12:54. Jazy, Norpoth, Clarke, Baillie and Keino were all in contention. On the curve Jazy took the lead and accelerated off the bend. He quickly opened a 6-meter gap. It was a dramatic attack, but could he maintain this lead? The most determined efforts to catch him came from Norpoth and Bob Schul, the latter initially slow to react. Along the back straight Norpoth and Schul moved a little ahead of the pack. Norpoth was within 4 meters of Jazy with 200 to go, and Schul was on his shoulder. Around the final bend Schul passed the German and closed to within three meters. Then Jazy looked back in desperation, giving Schul all the encouragement he needed. He passed the Frenchman with just over 60 meters to go and had a clear margin at the tape. Behind him Norpoth also passed Jazy with 40 to go, and then Dellinger just caught the faltering Jazy on the line to earn the bronze medal. Schul had run the last 300 in 38.7 and his last lap in 54.8. Norpoth and Dellinger ran 55.8 and 56.0 respectively. Behind the top four, Keino outsprinted Baillie for fifth spot. Only 2.2 seconds separated the first six.

Post Mortem: Schul ran a wonderful race, but he was lucky that Clarke didn’t make a more definitive break with his surging . Several times he chose not to react to Clarke’s surges and temporarily lost contact with the leading group. However, he did benefit from this risky tactic, as he didn’t expend as much energy on the surges as his competitors did. Jazy, with the pressure of a whole nation on his shoulders, expended too much energy in the first eleven laps, always going with the surges and always jostling for a good position near the front. Further, he made his run for the tape too early. Had he waited until the last 200, he might well have won the race. Clarke’s inexperience at world level, despite his 10,000 WR, was evident in his inability to control the race from the front. Norpoth ran brilliantly, but it is hard to imagine a scenario in which he would have won the race. Dellinger, who was actually the fastest in the last 100, misjudged his race: he could have been second. In short this race was a triumph for American distance running. The influence of an imported coach, Hungarian Mihaly Igloi, who had advised Schul, and of a homegrown coach, Bill Bowerman, who coached Dellinger, was an essential ingredient of this triumph. Cordner Nelson of Track and Field News summed up this race succinctly: “The total pace was slow but it contained so many surges that it wore out the runner with the most endurance as well as the one with the most speed.” (October/November, 1964, p. 12)

1. Bob Schul USA 13:48.8; 2. Harald Norpoth GER 13:49.6; 3. Bill Dellinger USA 13:49.8; 4. Michel Jazy FRA 13:49.8; 5. Kip Keino KEN 13:50.4; 6. Bill Baillie NZL 13:51.0.

10,000

This race was billed by Track & Field News as “the greatest 10,00 meters of all time.” There was a large field of 38 starters. Even more had entered and there was a strong lobby to schedule heats. As it turned out, the large field did affect the race in the last lap as the leaders had to dodge in and out of the 12 lapped runners. Clarke compared his last lap to “a dash for a train in a peak-hour crowd.” (Ron Clarke, The Unforgiving Minute, p. 19)

Almost half of the 38 starters had beaten 29:00 for 10,000 or the Six-Miles equivalent. With the WR at 28:15.6, this meant that there were a lot of runners who could be considered as potential medalists. The most favored was WR-holder Ron Clarke. The previous year he had surprised the world by knocking 2.6 seconds of Bolotnikov’s WR with 28:15.6. However, he was relatively inexperienced at international level. Bolotnikov, himself, was also in the field. The current Olympic champion at this distance still commanded respect at age 34. His form, however, was questionable. Another favorite was 5,000 Olympic champion Murray Halberg (31), who had an impressive 28:33 clocking to his name. The American hopes were in 18-year-old Gerry Lindgren and Marine Billy Mills (26), who had a best time equivalent to 28:56. The Russians, also had a fine specialist in Leonid Ivanov, who had been consistently improving his times in the 28:40s.

Pyotr Bolotnikov, the Olympic champion in Rome, led the field on a wet track with a brisk 64 first lap. When he slowed, Ron Clarke took the lead and was at the head of the field for much of the first half of the race. There were no attempts to break over the first 5,000. The kilometer times and the leaders were as follows: 1,000 Mills and Gamoudi (Tunisia) 2:42.0; 2,000 5:29.6 Clarke; 3,000 Wolde (Ethiopia) 8:20.9; 4,000 Clarke 11:13; 5,000 Mills 14:04.6. This WR pace reduced the lead pack to five runners: Mills, Clarke, Wolde, Gamoudi and Tsuburaya (Japan).

After the halfway mark, the Japanese was soon dropped. And over the four the next 4K Clarke tried to assert his authority: “My improvised plan was to accelerate every other lap in the hope of separating myself…. My pursuers held on.” (The Unforgiving Minute, p. 17) At one stage Mills dropped back almost 15 meters. But Clarke could not take advantage of this. The overall pace per K was very steady: Clarke led at all the splits: 6,000 16:57.9; 7,000 19:52.6; 8,000 22:47; 9,000 25:42.8. With three laps to go, Clarke felt confident of victory. Then Wolde, nursing a calf injury, dropped off, leaving just three runners to sort out the medals.

Under stadium lights that had just been turned on, the trio were locked together at the bell. Clarke and Mills were running side-by-side. Almost immediately they encountered a lapped runner on the crown of the bend who did not follow the etiquette of “moving out.” (Bolotnikov, Clarke recalls, was the only one who did move out when being lapped.) It was at the moment of overtaking that the drama occurred. Mills, on the outside, was reluctant to allow Clarke to run wide past the lapped runner. They bumped and Mills staggered across three lanes to his right. This allowed Gamoudi, who was right behind, to dash between them into the lead. The film shows clearly that Gamoudi grabbed Clarke’s shoulder at this point to get ahead. Mills recovered well and followed Clarke to chase down the Tunisian. Once in the lead, Gamoudi increased his lead to 7 meters by the start of the last bend. Then Clarke made his effort and quickly closed the gap. He managed to catch Gamoudi at about 80 from the tape. Mills lost ground on Clarke from the crown of the bend and seemed to be out of the race for first place.

|

| Billy Mills sprints past Gamoudi and Clarke for a clear vctory. |

Clarke’s great effort had brought him up to Gamoudi’s side, but he never got ahead, as the Tunisian managed to respond to his challenge. Mills meanwhile seemed to get a new life and quickly closed on the other two. He closed from 100-50 to go, and then exploded, roaring past Clarke and then Gamoudi for an astonishing victory. “His burst was so totally unexpected that it deflated both Mohamed and me,” Clarke recalled. (The Unforgiving Minute, p. 19) The first four beat the Olympic record; the times of the first three were impressive in view of the crowded and soft track.

Retrospect: Billy Mills ran a PB of 42 seconds and commented that he ran the race as if in a dream. He told Track and Field News: “I guess I was the only one who thought I had a chance. I figured if I stayed up there with the leaders, my speed would carry me in.” (Oct/Nov. 1964, p. 13.) Clarke following a talk with Murray Halberg, admitted that as WR holder he should have taken the initiative. But he wrote later: “Billy deserved to win for his persistence, his opportunism and his sound tactical sense in finally making his bid on the outside lane, which was firmer.” Gamoudi ran brilliantly but was lucky not to have been disqualified. Halberg (7th with 29:10.8 PB) ran well considering he was suffering from a virus. Bolotnikov (25th in 3 0:52.8) ran with an injury suffered just prior to this race.

1. Billy Mills USA 28:24.4; 2. Mohamed Gamoudi TUN 28:24.8; 3. Ron Clarke AUS 28:25.8; 4. Mamo Wolde ETH 28:31.8; 5. Leonid Ivanov USSR 28:53.2; 6. Kokichi Tsuburaya JAP 28:59.4.

Marathon

This race saw one of the most emphatic victories in Olympic history. Abebe Bikila of Ethiopia won by a margin of 4:08. Not since 1924, when Albin Stenroos of Finland won by 5:57, had there been such a winning margin. As second-place finisher Basil Heatley put it, “I won the B race, because we were outclassed by Bikila.” The Ethiopian’s victory was all the more amazing because he had undergone an appendectomy only six weeks earlier.

As the reigning Olympic champion, Bikila was the firm favorite for this race. However, his fifth place in the 1963 Boston Marathon showed he was not unbeatable. Still, he was clearly in good shape after two marathon victories at high altitude (2240m) in Addis Ababa (2:23:14 and 2:16:18).

The Japanese were likely to be a threat. The experienced Kimihara had won their trials with 2:17:11, while newcomer Tsuburaya finished only a minute behind. And they had finished in the same order in a later August race. The evergreen Belgian Vandendriessche had won the Boston earlier in the year and was always in contention in big races. Americans had established star Buddy Edelen, who had set a 2:14:28 world best in 1963, as well as 10,000 winner Billy Mills. Then there was a strong British trio of Brian Kilby, Ron Hill and Basil Heatley. Heatley and Hill had both broken Edelen’s World Best earlier in the summer with 2:13:55 and 2:14:12 respectively; Kilby was the reigning Empire and European champion. Also of note was Mamo Wolde, who had pushed Bikila in his second Addis Ababa marathon to finish only 0.4 of a second behind. Then there was a wild card in Australia’s Ron Clarke, who had run so well on the track without earning a gold.

|

| At the turnaround, Hogan is still hanging on to Bikila. No one else is in sight. |

Ron Clarke was the early leader he went through 5K in 15:06, with Irishman Jim Hogan on his heels. Bikila was 11 seconds back. Clarke maintained the fast pace, passing 10K in 30:14. Hogan and Bikila were with him. They had a 25-second lead on the strung-out field behind them. The leading trio were still together at 15K (45:35); the chasing group (46:41) comprised of Ambu (Italy), Temu (Kenya), Vagg (Australia) and Suto (Hungary).

In the next 5K (60:58) Bikila moved into a 5-second lead over Hogan and a 41-second lead over Clarke. The next group (62:46) comprised of Demissie Wolde and Tsuburaya, Suto and Ambu having dropped back. Bikila passed the turnaround in 64:28 with Hogan still close. By 25K Bikila (1:16:40) had 15 seconds on Hogan; Clarke was still third (1:18:02) but he was being pressed by Suto, Tsuburaya and Wolde. A group in seventh was almost 3:00 behind the leader: Kimihara, Heatley, Kilby and Mills.

At 35K the front positions were the same: Bikila 1:49:01; Hogan 1:51.27; Tsuburaya and Suto 1:51:45. The big change was behind, where Heatley (1:52:13) had moved into fifth. Kilby was only four seconds behind him, while Clarke was seventh ahead of Wolde, Vandendriessche and Edelen. Hogan’s retirement soon after 35K left the Japanese Tsuburaya in second, but he was 2:52 behind Bikila (2:05:10) at 40K. Behind him Heatley and Kilby had overtaken Suto. Heatley then began to move away from his team-mate and close in on second-place Tsuburaya. “I didn’t expect to catch him,” Heatley recalls, “but he was a target. He came back faster than I expected. As we approached the stadium, it was obvious I was going to get very close to him if not past him.”

|

| Heatley finishes in second place in front of Tsuburaya. |

Bikila entered the stadium with a huge lead and ran elegantly to the tape. He appeared relaxed and did some exercises to show the crowd how fresh he was. The drama was behind him. Tsuburaya entered the stadium in second place, but Heatley was close to him. Then in the last 200 Heatley produced an unanswerable sprint to win the silver. He recalls this unforgettable moment: “It wasn’t until we were in the stadium with 250-300 to go that I was within 20-30 yards of him. There‘s that instinctive moment when you know, after many years of racing, that it’s time to go. I grabbed a 2-second lead before he knew what had happened.”

In fourth place, Kilby showed how consistent he was in big races. He had run with Heatley for almost the whole race but didn’t quite have the strength to stay with him after 40K.

1. Abebe Bikila ETH 2:12:11; 2. Basil Heatley GBR 2:16:19; 3. Kokichi Tsuburaya 2:16:23; 4. Brian Kilby GBR 2:17:02; 5. Jozsef Suto HUN 2:17:56; 6. Buddy Edelen USA 2:18:12.

2 Comments