With his talents, American miler Bill Bonthron could have conquered the world. He had strength, speed and a tenacious competitive drive. But while he performed brilliantly in his own country and even set a world record for 1,500 in 1934, he made little impact on the international scene and never competed in an Olympic Games. Following the traditional amateur conventions of his time, Bonthron planned his athletic career for just the four years of his university education. Once he graduated and married, his priority was his job as an accountant and he announced his retirement from running in 1934. Although he later broke with convention and continued to train seriously in his spare time, he never regained the form of his university years and failed to qualify for the 1936 Berlin Olympics. He did make one European tour in his graduating year, but failed to live up to the reputation that had crossed the Atlantic before his arrival.

Glenn Cunningham Profile1909-1988 The life of 1930’s American miler Glen Cunningham has now become part of American folklore. It is the story of a young Kansas boy of pioneer farming stock who faced adversity with courage and determination to become a world-famous hero. This story, as it grew into folklore over many printed versions, has often been embellished with fictional details. However, the actual facts are powerful enough. When just seven years old, Glenn Cunningham was badly injured by a woodstove explosion that killed his brother. He spent over a year recuperating upstairs in his parent’s home before he was able to venture outdoors. His legs were so badly burned that it took him more than six months to stand, yet alone move. Yet through determination and self-discipline he learned to walk and then to run, eventually becoming a world-class runner.

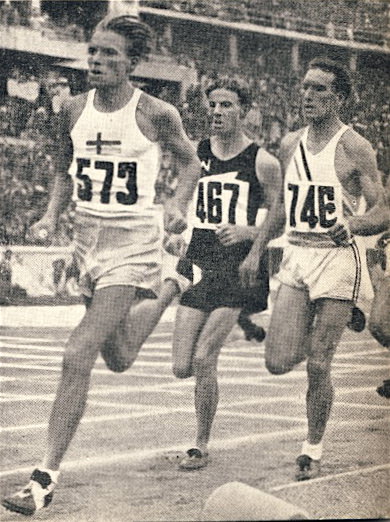

The three favorites for this Olympic final were all reaching the climax of their careers. Luigi Beccali (29) of Italy had broken the WR for 1500 in 1933; he was also the reigning Olympic and European 1,500 champion. American Glenn Cunningham (25) was the current WR holder for the Mile, and he had been fourth in the 1932 Olympic 1,500 final. New Zealander Jack Lovelock (26) had set a Mile WR in 1933 but had not subsequently run as well. Still, a recent 3:01 time-trial over 1,200 showed he was back to his best form. These three great runners knew each other well from previous encounters on the track. Beccali had the best record, having beaten Cunningham once and Lovelock twice. Cunningham had beaten both men once, while Lovelock had beaten Cunningham three times. All three were known for great finishing kicks, so it promised to be a tactical race.

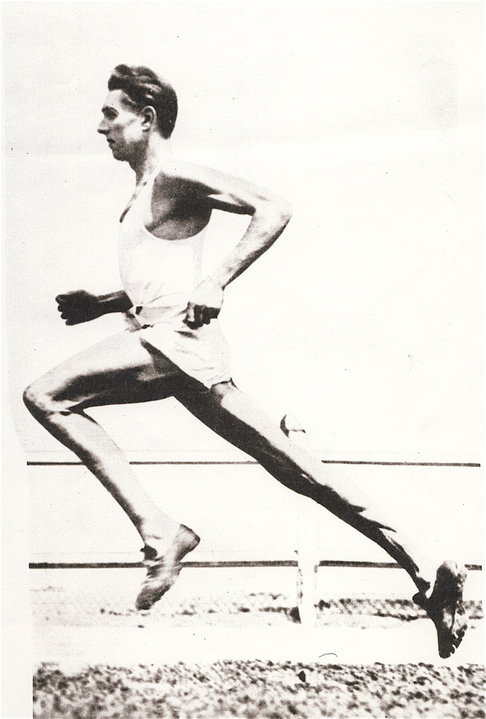

PROFILE: JACK LOVELOCK 1910-1949 An Olympic champion and Mile WR holder, this New Zealander dedicated himself to becoming a complete runner. He applied a professional attitude to an amateur activity. According to Jerry Cornes, the President of Oxford University AC when Lovelock arrived there in 1931 as a Rhodes Scholar, “Lovelock…tried hard to know himself and was single-minded in his efforts to eradicate his weaknesses and to exploit the best in his mental and physical make-up. He was a pioneer in the analytical study of the one-mile and 1500-metre races.” Cornes, himself a fine runner and Olympian, went on to say that Lovelock “contributed in no small measure to what I will always regard as the final achievement—Bannister’s breaking of the ‘sound barrier’ of the four-minute mile.” (Quoted in Norman Harris, The Legend of Lovelock, p.9) Indeed it is interesting to compare Lovelock with Bannister: both developed their running careers while training to be doctors, both studied at St. Mary’s in London, both were highly strung, and both broke the Mile world record.

Olympic 5,000, Stockholm 1912Great Races #2 This great race was contested by the two leading runners of the time; both were considered almost unbeatable. Their superiority over all other runners was huge. And in the heat of this race the WR was decimated by an unbelievable margin.Frenchman Jean Bouin, 23, looked more like a boxer than a runner. He was thought to be overweight but said, “I haven’t got an ounce more fat to lose.” Bouin relied mainly on enthusiasm and was not considered hugely talented. But he was tough, making his name in cross-country. He had been national champion since 1909, and after running second in the 1909 International CC race, was the international champion for the next two years.

Jules Ladoumègue Profile1906-19731.71 (5’7”) 59kg (130 lbs) Not many runners can attract a 300,000 crowd to watch a ceremonial run in a city street. But on a gloomy and foggy November day in 1935, French runner Jules Ladoumègue did just that when he ran the length of the Champs Élysées to receive the homage of the French people. He had been banned from competition for nearly four years, yet the French people still remembered their beloved “Julot.” His popularity stemmed not only from his brilliant short career of six world records and an Olympic silver medal but also from his exquisite running style and his sensitive and endearing personality. For someone who had experienced several tragedies in his early life, the cheering of the massive crowd on that drab November day must have been all the more inspiring.

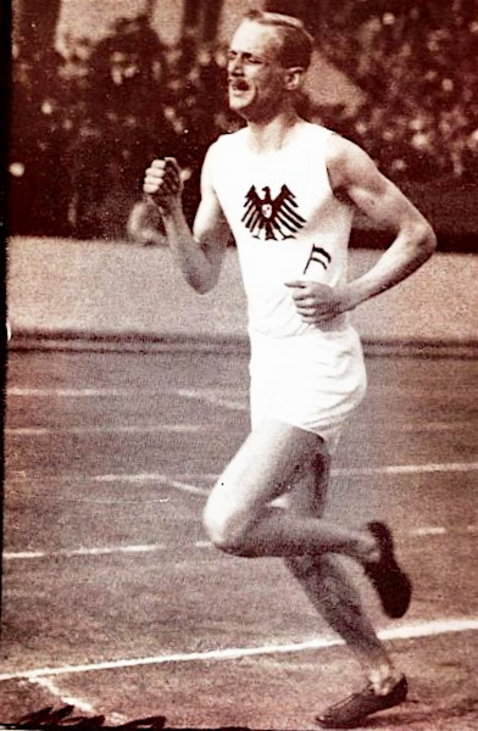

Otto Pelzer Profile 1900-19706ft 1/186cm 159lbs/72kg Peltzer was a fierce and successful competitor, but he is now mainly remembered for his 800, 1,000 and 1,500 world records. His 1:51.6 broke James Meredith’s 14-year-old 800 record by 0.3 of a second and lasted two years; his 2:25.8 broke Séra Martin’s one-year old 1,000 record by exactly one second and lasted three years; and his 3:51.0 broke Nurmi’s two-year-old 1,500 record by 1.6 seconds and lasted four years. (He also claimed a world record in the 500m (1:03.6), an event rarely run.)

PROFILE: PAAVO NURMI1897-1973 Finnish runner Paavo Nurmi was truly a legend in his own lifetime. In the 1920s he was by far the dominant distance runner in the world. He improved world records by the following margins: 1,500: 2.1 seconds; Mile: 2.2 seconds; 3,000: 12.8 seconds; 5,000: 8.4 seconds; 10,000: 52.6 seconds. Nurmi also broke new ground in racing and training techniques. In his training he developed an ability to judge his speed. He understood the need to run at an even pace when attacking records and carried a stopwatch in his races. He trained twice a day and did some speedwork. Later, he admitted that he did too much steady running at the expense of fast intervals.

Parades across the world are often military, the Russian May Day Parade for example. But there are many other types of parade—processions of people along a road that celebrate historical events (the end of World War 2) or promote groups of society (the Brazilian Rio Carnival Parade). And of course there is always a Parade of Nations to open the Olympic Games. A unique parade was held in Paris, France, on November 11, 1935. It was organized by the newspaper Paris-Soir to pay homage to a runner who had been banned for life some four years previously. Jules Ladoumègue had captured the hearts of his nation when he had broken six world records and won an Oålympic silver medal. A very sensitive and modest man, “Julot” nevertheless appealed to the French, who were still recovering from German occupation in World War 1. He also appealed to the public with his elegant running style.

Peltzer v Lowe: Great Races #26 880 AAA British Championships, July 3, 1926 With the First World War only eight years in the past, it was quite a talking point when German 800 runner Otto Peltzer entered the 1926 British Championships. Germany had not been invited to compete in the Paris 1924 Olympics, but clearly the British authorities, two years later, were more forgiving. And there was added interest in the fact that Douglas Lowe, the 1924 Olympic champion for 800, would also be competing. Peltzer, as 1924 German champion over 800 and 1,500 would have competed in Paris had Germany been invited, so he clearly had something to prove. It was Britain against Germany again, but this time on the Stamford Bridge running track rather than on the battlefields of Europe.