Anders Gärderud Profile

b. Aug. 28, 1946

6’1” (1.86 m) 154 lbs (70 kg)

|

The story of Anders Gärderud is a story of promise fulfilled. It’s also a story of setbacks and of the need for a radical reassessment of a running career. Gärderud has been Sweden’s greatest runner since Andersson and Hägg. Thirty years after these two great runners had rewritten the record book for 1,500 and the Mile, he broke the world Steeplechase record four times over a four-year period, reducing it an amazing 12.6 seconds. And he capped off his career in the best way possible with an Olympic gold medal in a world-record time.

Behind this ultimate achievement were 12 years of training and competition. Gärderud came to attention early with a Junior world record in the 1,500 Steeplechase. His talent was plain to see. But after some promising years, his career stalled and he was tempted to return to his other sport, orienteering. As well, he became burdened with a reputation for failing in major meets. At the age of 25, he had to reassess his running career and make radical changes. For the next five years he consistently improved his times and his racing. This improvement culminated in the fairytale climax in the Olympics.

-----------

Early Promise

Born into a sporting family, Anders followed in his father’s footsteps and started orienteering competition at the age of 12. Three years later, at 15, he began track competition. Success was almost immediate when on July 17, 1964, he won the 3,000 Swedish Junior title in 8:27.5. In August he set a Swedish Junior record for the 1,500 Steeplechase with 4:08.5. He then went on to claim the 1964 European Junior 1,500 Steeplechase title with 4:08.0 on September 20, winning by 5.1 secs. This time was a Junior world record.

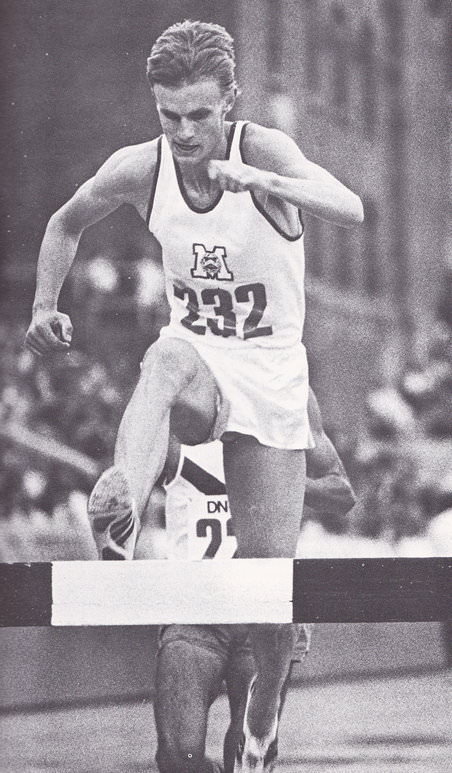

|

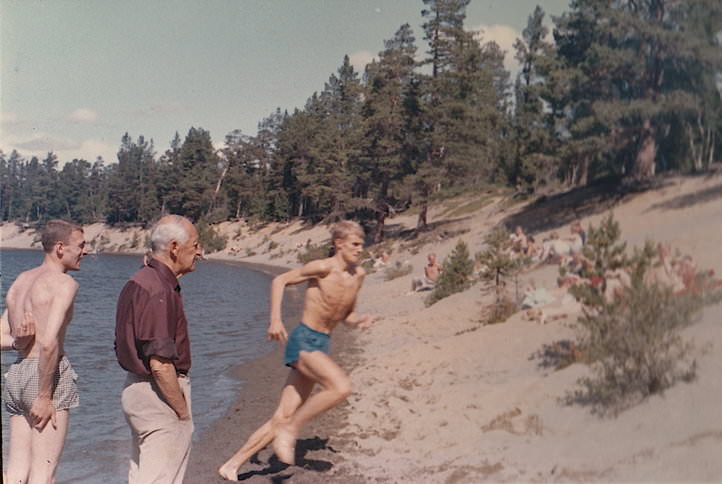

| Gärderud leads a group of Spanish internationals at Vålådalen underthe watchdul eye of Gösta Olander. |

After these successes, Gärderud decided to train seriously for the track. In the following year, while still a Junior, he broke his Junior Steeplechase world record twice more with 4:02.6 and 4:00.8. On the flat, he improved the Swedish Junior 1,500 record four times from 3:50.3 to 3:45.1. Even more impressive was a Mile just before his 19th birthday when he ran 4:01.9 behind Odlozil, Simpson and Wheeler. This was another European Junior record. In 1965 he ran the 3,000 Steeplechase for first time, breaking the 9:00 barrier with 8:59.4. He also earned his first Swedish Senior vests in internationals against Norway, West Germany and Finland.

Gösta Olander, who had coached Hägg, saw great potential in Gärderud. He told Robert Parienté at this time: “I know a young runner who spends long periods here at [Vålådalen] and whose talent only needs an exclusive commitment to running to blossom. His many gifts are dazzling: he could shine from 800 to 5,000 as well as the 3,000 Steeplechase. His supple gait overwhelmingly reminds me of Hägg. His power from the rear leg makes his stride really efficient. Gärderud is capable of recapturing Sweden’s former middle-distance glory.” (Parienté, La fabuleuse histoire de l’athlétisme, p. 481. My translation.)

The next year, 1966, was really a consolidation year. Focusing instead on the 1,500, he ran the event 13 times, winning four. But he only improved his 1964 time by 1.7 seconds to 3:43.2. In the European Championships he performed well in his 1,500 heat and was only 0.1 of a second out of a place in the final with 3:45.8. Showing good strength for a 20-year-old, he later ran under 14:00 for 5,000 with 13:56.

European Status

|

| Vålådalen, 1966. Olander supervises Gärderud's sandhill session. |

Gärderud started off his 1967 season at a new level with three 1,500s, all faster than he had ever run (3:41.7, 3:41.2, 3:41.8), but each time he was beaten by fellow Swede Ulf Högberg. He followed these with a 13:49.2 PB over 5,000. Then in a Euro Cup Semi, he ran 3rd and 2nd over 1,500 and 5,000, beating such fine runners as Zhelebovski and de Hertoghe. At the end of July he beat Högberg for the first time with 3:42.0. And in August he beat him five consecutive times, the last time running a PB 3:39.6. Late in August he ran a Swedish record for 3,000 with 7:56.0. By focusing on the 1,500 in 1967, Gärderud at age 21 established himself as Sweden’s number one and showed he could race with Europe’s best.

Gärderud has said that he was not ready for this new status: “I was already at age 21-22 an international star in Sweden! The problem however was that I did not regard myself as one. I was not running to beat the world-class athletes. National victories were quite enough for me in those days.” (Seppo Luhtala, ed., Top Distance Runners of the Century, pp.100-1) It would be a few years before his attitude changed and he sought international success.

First OlympicsHis 1968 Olympic year started at a fairly low key as he needed to peak late—in October. Up to the Swedish championships in mid-August, he again concentrated on the 1,500 with eight races. He won only three of these; his fastest was 3:40. He also ran one brisk 5,000 (13:53.7). In the Swedish championships he was second in the 800 (1:54.5) and first in the 1,500 (3:51.8). It was only after this, in mid-August, that his times came down: a national record in the 3,000 with 7:55.0, a PB 800 in 1:48.8, and a 3:38.7 PB in the 1,500 behind Bodo Tümmler. Then, from August 26 until September 12, he competed for Sweden in a series of international matches. He won three of his five races, posting an 800 Swedish record in Rome with 1:47.2. He was rounding into his best form.

But he disappointed in Mexico. This was really not surprising as it was his first Olympics. He ran reasonably well in his 800 heat, placing fourth with 1:48.9, which was 1.7 seconds slower than his recent PB. But he ran poorly in the first round of the 1,500, finishing back in seventh with 3:54.2.

Setback

Gärderud’s experience in Mexico had an adverse effect on his running career. Although he continued to train and race, orienteering began to take up more of his time. This sport was just as enjoyable to him and he was good at it. Running on the other hand, especially the big competitions, was much more stressful. “I had several conflicts between running and orienteering during my career,” Gärderud has explained, “sometime to the extent that that I seriously considered leaving running.” (Luhtala, p. 99)

He raced only 16 times in 1969—compared to 27 the previous year. And his times were slower: 3.2 second slower over 800, 4.4 over 1,500. But there was one significant change in his race schedule; he tried the 3,000 steeplechase again. He had run only one before: an 8:59.4 back in 1965. In fact he started his 1969 season with a 3,000 Steeplechase and clocked an encouraging 8:38.6. Two weeks later he encountered tougher competition, including Kerry O’Brien, and was only fifth in 8:47.2. Perhaps discouraged, this second steeplechase was his last in 1969.

At an age (23) when he should have been improving every year, Gärderud seemed stuck in a groove. Many people must have been wondering whether he was going to fulfill the enormous talent that Gösta Olander had recognized. As Robert Parienté has written, “Gärderud returned from Mexico discouraged. He distanced himself from track and in 1970 and 1971 participated in 25 orienteering competitions…. He was forgotten by track enthusiasts.” (p. 480)

In 1970 he ran 1,500 for eight of his 18 races, but he could run only 3:43.0 and didn’t win any of them. And he placed only fourth in the 800 and 1,500 in the Swedish Nationals. Significantly he did not run a steeplechase until September. He ran four that month and won only one of them: 8:48.2, 8:45.6, 8:46.4 and 8:56.6.

Turnaround

|

After two years of no progress, Gärderud changed his attitude toward track. However, the crucial turnaround didn’t come until late in the 1971 season. He had started off the season with an emphasis on the steeplechase, running 8:40.4, 8:39.8 and then a PB 8:35.8 in the early season. He ran four more before the Europeans in mid-August, with one of them sub-8:40. But there was little in these seven steeplechases to suggest how well he would run in the Euro heats. Track journalists were surprised when he won his heat with a huge 7.5 second PB in 8:28.32. Track & Field News, for example, called Gärderud “a built-up miler” with some justification, bearing in mind he had only run one 3,000 Steeple before 1970.

The Euro final was a huge setback. Although it was won in a time only two seconds faster than his heat time, he was far back in tenth place (8:39.6), 14.4 seconds behind the winner, Villain of France. After raising hopes significantly with his heat victory, Gärderud again experienced a let-down in a major championship. He clearly wasn’t injured or unwell, as he continued with competition just four days after his final. One can only conclude that the pressure got to him after his superb heat. Indeed, he has admitted to being vulnerable to nerves in his early career: “Many times I was feeling over-excited before races…. It got worse later when everybody was expecting me to become another Gunder Hägg. I was not always able to control my nerves. It took a long time before I finally got hold of my self-confidence after many years of hard training.” (Luhtala, p. 99)

However, the Euro experience in Helsinki was crucial in his turnaround: “I finally got the real inspiration in Helsinki during the 1971 European Championships when I saw Juha Väätäinen win the 5,0000 and 10,000 metres gold medals. It was only then that I realized I also could reach the top. If Juha could do it, then why couldn’t I?’ (Luhtala, p. 101) Väätäinen had inspired Gärderud by winning the Euro 5,000 and 10,000 in grand style in front of his home crowd.

Following the Games, Gärderud contacted Väätäinen and sought advice from him. Later he joined the Finn for warm-weather training in Spain. As well, he began regular trips to Vålådalen for training. After vacillating between track and orienteering for several years, he had finally decided to dedicate himself to the Steeplechase. This was the time his famous formula was put into practice: 2x7x52x5. This formula for success said that an athlete must train twice a day, seven days a week, and fifty-two weeks a year for five years. Through his connection with Vaitainen, he took up some of Arthur Lydiard’s training concepts and began to run more mileage, up to 150 miles a week. It was therefore a changed Gärderud who began his winter’s training at the end of 1971 and who was to win Olympic gold at the end of five years of dedicated graft.

Upwards

Thus began a rejuvenation of Gärderud’s career. Results came quickly in 1972 after his winter’s conditioning. On June 8 in Helsinki, he won a steeplechase from Kantanen in a new PB of 8:24.6. Then after another win in 8:36.8, he improved even further to 8:23.6 in Stockholm. Nine days later, he suffered a rare defeat to Kantanen (8:26.6 to 8:27.4). Two national records followed in quick succession: a 5,000 in 13:35.8 (first) and a Two Miles in 8:20.6 (third). In the 5,000 he beat Gammoudi and Pollenius; in the Two Miles he finished behind Viren, who set a world record of 8:14.0, and Puttemans, but ahead of Stewart, Quax and Bedford. Clearly he was now in the very top rank of world-class runners and clearly a favorite for the Munich Olympics.

Two weeks before the Games, he lost again to Kantanen (8:23.0), but this time set another PB of 8:23.4. Everything looked promising for an Olympic medal. But the big-meet jinx struck again, and he failed to qualify for the final. Gärderud was reported to have a cold. Parienté said he suffered from stage fright. (p. 482) Athletics Weekly reported he “folded in the last 50 yards after looking so relaxed throughout.” (Sept. 9, 1972) And the prestigious commentator Dick Bank wrote : “Anders Gärderud showed again he is not a pressure runner.” (AW Jan 13, 1973) It was not as if he ran really badly. Clocking 8:30.8, he was only 1.8 behind the winner of his heat and only 0.4 out of a qualifying position. But based on his brilliant performances in the two months before, he should have been able to qualify easily. “I thought I was ready,” he said later, “but I soon noticed I had been wrong. I didn’t know yet the requirements for being a winner.” (Luhtala, p. 101)

Out of the blue, redemption came two weeks after the Olympics in an international meet in Helsinki. In a tight race with Kantanen, Gärderud won in a new world record of 8:20.7, just 1.2 seconds below O’Brien’s mark. If only he had run like this in Munich!

More Work

He had confirmed he was a great runner; now he had to prove he was a great competitor. With four years to “work on my problems” (Luhtala, p. 101), Gärderud went into his second year of his five-year plan. He was reputed to have been “putting in the miles” over the winter. And there was renewed interest in his career now that he was the Steeplechase WR holder. In the 1973 season he ran seven Steeplechases, improved his PB by 4 seconds but nevertheless ended the season no longer holding the world record.

After an early Steeplechase in Japan (8:33.8) and some warm-up flat races in June, he quickly showed that he was in top form with an 8:21.2 in Helsinki. However, he was beaten in this race by 7.3 seconds! Olympic silver-medalist Ben Jipcho of Kenya, having already bettered Gärderud’s WR with 8:19.8 early in the season, ran a stunning 8:14.0. Such a drastic lowering of the WR (5.8 seconds) must have been a huge shock to Gärderud, not to mention the margin of his loss in the race.

Gärderud’s response came a week later in Stockholm, when he met Jipcho again. This time, in front of his home crowd, he gave the Kenyan a real race, finishing just 0.16 seconds behind in a PB of 8:18.39. Soon after, he improved on this time in the Euro Cup Semi-final with 8:16.06. And although this time was not accepted because the water jump was a few centimeters short, Gärderud had proved that Jipcho’s time was in reach. As well he had been able to give him a close race in Stockholm. He had risen to the challenge of becoming a better competitor.

Very Close

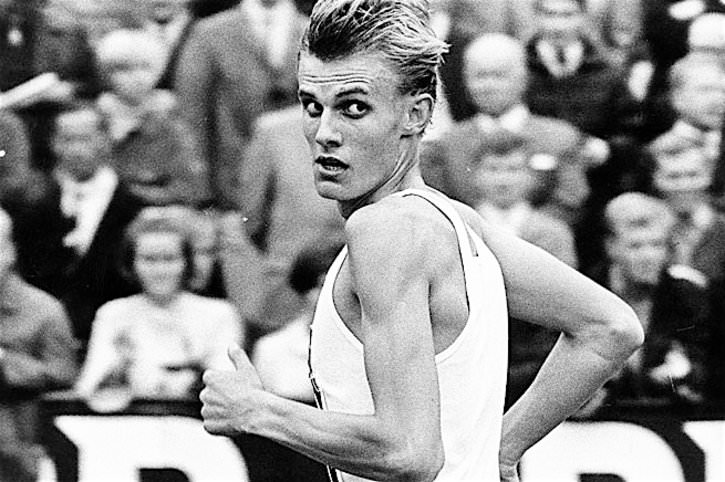

|

| Gärderud beats rival Malinowski. |

Gärderud, now 26, began his 1974 season as usual with some low-key races that included an 8:29 Steeplechase and a 13:48 5,000. He was ready for a good run in Helsinki at the end of the June, and although he ran a fast time (8:19.71) he was again second. This time it was the German Karst (8:18.5) who beat him. Still, Gärderud was in fine form and he ran an 8:15.2 PB ahead of Kantanen a week later.

Then, after running two fast 1,500s (3:37.47, 3:36.72), he improved yet again in another Helsinki race. This was an all-out WR attempt. Sadly, the early pace was just too fast. Leading all the way, he passed 1,000 in 2:40.7, which is 8:02 speed. Kantanen held on until the halfway mark (4:05) and then soon dropped, even though Garderud slowed to a 2:48.8 second K. And although he managed a desperate 63.2 last lap, he finished a tantalizing 0.2 outside Jipcho’s WR, with 8:14.2. This brave run at least earned him a European record.

All looked good for the Euros in Rome three weeks ahead. Two races immediately before the Games boosted his confidence even more: a 13:25.2 PB for 5,000 and a Steeplechase win over Kantanen in a Sweden v Finland international (8:20.8).

He qualified for the Euro final comfortably with 8:23.61. In the final his main opponents were Kantanen of Finland, whom he was now beating regularly, Karst of West Germany, who had beaten him earlier in the year with an 8:18, and Bronislaw Malinowski, who had run in the low 8:20s the two previous years. And it was Malinowski who eventually took up the lead. Kantanen had fallen twice and was far back. Only Gärderud, Fava of Italy and Karst were still in the hunt. First Fava and then Karst dropped back to leave just Gärderud leading Malinowski at the bell.

The Pole waited until the back straight to make his move to the front. Gärderud looked comfortable keeping in contact and was on Malinowski’s shoulder as they entered the straight and approached the last hurdle. It was at this hurdle that the race was decided, for Malinowski gained ground over the obstacle and this seemed to deflate Gärderud. He began to lose a little more ground and then, twelve strides from the tape, looked back to see if he was a safe second. It’s hard not to conclude that he ceded victory too soon. Still, it had been a great race. Malinowski had PB-ed when it counted with 8:15.0; Gärderud was just 0.37 back with 8:15.4. This was by far his best major-meet performance, but he still hadn’t won.

Two World Records

In the three years in his five-year plan, Gärderud had progressed well. His Steeplechase time was dropping steadily and he was proving to be a better competitor. His fourth year had no major meets, but there would be several chances to regain the world record from Jipcho, whose 8:14.0 mark still stood. His first major race came in Stockholm in early June—against his Euro rival Malinowski. They dead heated in 8:15.37. This was a different Gärderud from the one who had lost to Malinowski in Helsinki; this time he fought against the Pole all the way to the tape.

Then in one week, Gärderud broke the world record twice. The first WR came in a June 25 match against Norway and East Germany. Leaving Baumgartl, Strauss and Kvalheim well behind, he ran splits of 2:47, 2:43 and 2:40.4, passing the 1,500 mark in 4:08, to obliterate Jipcho’s mark by 3.6 seconds with 8:10.4. Baumgartl was eight seconds behind in second. Incidentally, this was Gärderud’s 50th Steeplechase.

A week later, after running a 3,000 in 7:55.6 (2nd) and a 3:54.45 PB mile (5th), Gärderud met Malinowski for the second time on July 1. The Stockholm race also included Kantanen and Karst. After the Kenyan Mogaka had taken the field through 1K in a brisk 2:40.5, Malinowski took the lead at 1,200 and kept the pace fast. He passed 1,500 in 4:04 and 2K in 5:28.6. Behind him Gärderud ran easily, in contrast to the Pole’s somewhat laboured gait. The two were locked together until 300 out, when Gärderud attacked decisively, quickly opening up a gap of more than 10m. With a blistering 27.5 last 200, the transformed Gärderud was 2.8 seconds ahead at the tape, recording a new world record of 8:09.8. It was the third time he had broken the world mark.

After the race, Garderud said that with the WR already his, he just wanted to win, “I knew [Malinowski] had the idea of beating my record, so I followed him. I delayed my attack so I would have more to resist him with. I imagine I lost about a second doing this.” (Track & Field News, 16 Sept. 1975)

|

| Gärderud chases Poland's Malinowski in one of their manySteeplechase duels. |

Following his second WR in a month, the rest of Gärderud’s 1975 season was anticlimactic--except for a fine 2,000 three days later behind Kiwis Walker and Dixon, but ahead of Puttemans, Brendan Foster and Ian Stewart. His time of 5:02.9 was a Swedish record. After that, he fulfilled his obligations to the Swedish team with victories in the Euro Cup, and against Finland and Czechoslovakia. He won the national title in the Steeplechase (8:32.18) and then broke his Swedish record for 5,000 with 13:25.0 behind Dixon and Liquori. But his season was really over, despite a few more races, none of which he won. He was just third in a Steeplechase in London at the end of August, finishing 7.46 seconds behind Malinowski and ceding second place to Karst of West Germany.

Clearly he had found the right formula for winter training; he had improved his steeplechase time each of the five years since 1971. He would need to improve again to have a chance of winning in the Montreal Olympics. It must have been a great strain on him in view of his reputation in the media, fair or unfair, for failing in the big championships.

Olympic Year Again

During his Olympic preparation Gärderud took part in the Sao Paulo New Year’s road race (33rd) and the international cross-country championships (52nd). His track season began a little later than usual on June 1 with a 1,500 win in 3:40.4. Two days later he won the 5,000 in the Helsinki Games, beating Puttemans, Päivarinta and Vainio in 13:44.0. He was clearly running his races to win. He beat Puttemans in a close race by 0.4 of a second. His next race was also a close victory, an 8:15.2 giving him a winning margin of just 0.52. And although he did lose a 5,000 to Päivarinta by 1.2 seconds, he won the World Games Steeplechase by 1.4 seconds ahead of Kantanen, Glans and Malinowski (8:16.74).

In early July, just three weeks before the Montreal Olympics, he ran a very fast 5,000, shattering his PB by 7.41 seconds with 13:17.59. Although he was only fourth behind Quax, Hildebrand and Dixon, this was a good race for his final Olympic build-up. It showed that he was in better shape than ever.

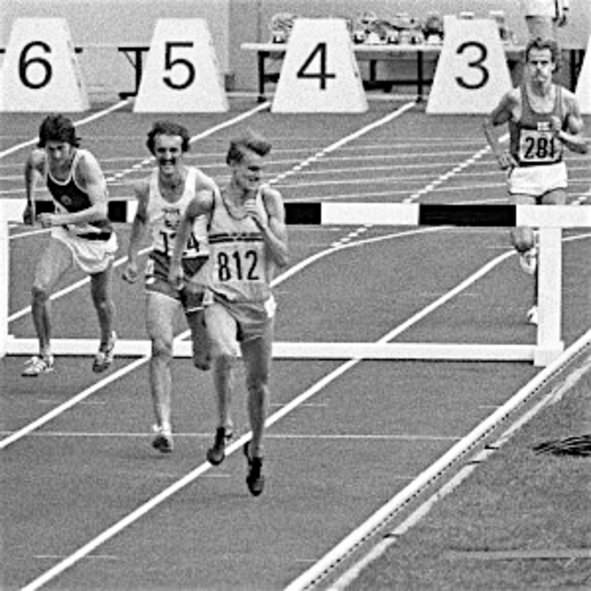

1976 Olympic Final

In Montreal there were two heats in the Steeplechase, with the first six qualifying for the final. Athletics Weekly reported that Gärderud “was content to lope in 20m behind” Malinowski in third. (August 7, 1976) His time was 8:21.4. However, there was some cause for concern, for Gärderud had strained a calf muscle in a recent training session.

The final, two days later, was full of excitement, and despite the muggy conditions it produced a new world record. In the early laps, Gärderud ran easily in fifth and sixth place, Antonio Campos of Spain led at 1K in 2:43.6, which was 3.1 seconds slower than Gärderud’s WR run in 1975. Then Malinowski, concerned about his finish in a slow race, especially with Baumgartl running, took the lead at around the halfway point and upped the pace. He passed 2K in 5:29.1 (2:45.5 second K). Soon Malinowski’s pace had dropped all of the field except Baumgartl, Gärderud and Kantanen.

The Finn eventually dropped off the pace and at the bell was 5m back of the leading trio, with Malinowski still ahead. The Pole kept up the pressure round the bend, but it made no impression on Gärderud, who launched an attack at the start of the back straight. He immediately opened up a gap, but then Baumgartl and Malinowski, battling for second with the Pole holding off the German, closed back up to Gärderud. After clearing the back-straight hurdle together, Baumgartl managed to pass Malinowski just before the water jump.

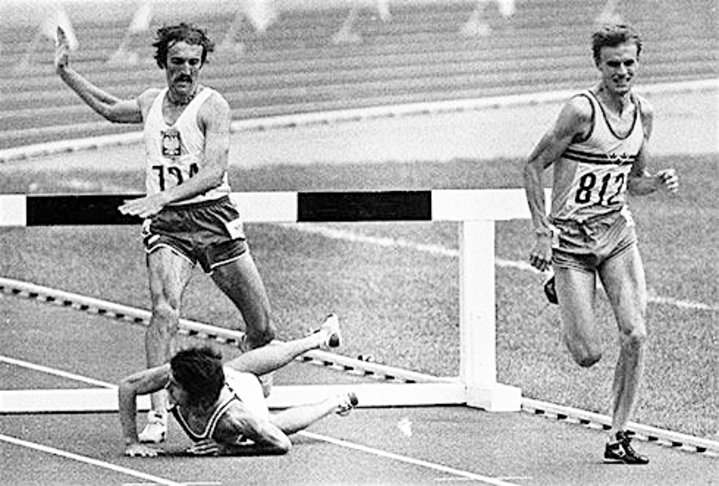

Still ahead, Gärderud opened a small 4m gap at the water jump with a fast approach. However, Baumgartl quickly chased down Gärderud and was on his shoulder as they entered the straight. Malinowski was beginning to lose contact. At the final hurdle, Gärderud lifted his lead leg just a fraction ahead of Baumgartl. He was careful over the last hurdle, placing his foot on top rather than hurdling properly. In contrast, Baumgartl went at the hurdle “like a 400m hurdler” (Parienté, p. 485) and fell after hitting it with his rear foot. While Malinowski jumped over a prone Baumgartl, Gärderud strode on alone and felt comfortable enough to look back. He saw he was well ahead and could coast the last 15m. An Olympic gold was not the only reward for his great run; he had also lowered his world record again to 8:08.2. Covering the last K in a very fast 2:38.9, he had reduced the WR by 1.7 seconds.

|

| Montreal: Gärderud is well clear as Malinowski chases him and Baumgartl recovers. |

|

| Montreal: Gärderud takes the lastwater jump well and opens up a gap ahead of Baumgartl and Malinowski. |

|

| Montreal:Baumgartl has fallen at the last hurdle. Malinowski is about to hurdle him. |

Could he still have won if Baumgartl hadn’t fallen? “I don’t know,” he told reporters. “I was tired, but I think he was more tired than I was because he hit the hurdle.” (1976 Olympic Games, Dave Prokop, p. 171) Baumgartl was also asked this question: “I don’t even want to speculate on whether I would have won,” he said. (Athletics Weekly, August 14, 1976)

The rest of Gärderud’s 1976 season could only be an anti-climax. Emotionally spent, he raced Malinowski in front of his home Stockholm crowd two weeks after the Olympics. It was a good race, but not surprisingly Malinowski, who needed the victory more after his defeat in Munich, won a close race (8:12.23 to 8:13.11). Three weeks later, Gärderud ran one more steeplechase for his country in a match against Finland. All he could manage was fourth place in a time of 8:42.29.

Winding Down

After his Olympic victory, the 30-year-old Gärderud made a commitment to race one more year. Of his eleven races in 1977, he won only one—an 8:48.5 Steeplechase. His early-season flat races produced some reasonable times (3:43.49, 13:53.73 and 7:54.9). then in July and August he ran three steeplechases in the 8:31-8:32 range. One of these was in the annual Galan Stockholm meet and the two others were for his country in the Euro Cup and against Finland. It was a quiet ending to his career.

Conclusion

An intelligent and sensitive man, Anders Gärderud was blessed with immense talent and with a healthy sporting background. That background saw him growing up with orienteering, a sport that he has always loved. This sport was less stressful than track racing, and he was at times close to forsaking the Steeplechase for a compass and map. He clearly found track racing taxing: “It’s a difficult event, demanding on the muscles, the stomach and the nerves,” he has said. “You can’t master it without sacrificing a lot.” (Parienté, p. 486) But he took up the challenge of track racing, although it wasn’t until he was in the middle of his career, at age 25, that he finally decided on a full commitment to the Steeplechase. It took him five more hard years to achieve his ultimate goal and to fulfill his promise.

1 Comment