Sydney Wooderson New Profile

1914-2006

|

One of the great all-time British runners, Sydney Wooderson would surely be even more celebrated today had he been able to compete fully fit in an Olympic Games. Unluckily, in the only Games he qualified for, the 1936 Berlin Games, he ran with a broken bone in his foot and didn’t qualify for the 1,500 final. The next two projected Games in 1940 and 1944, when he would have been at his peak, were not held because of war.

There is little doubt that he could have been an Olympic champion, for he almost always rose to the occasion of a major race. He won both times he entered the European championships, with victories in the 1,500 in 1938 and in the 5,000 in 1946. As well, as a 19-year-old he earned a silver medal in the 1934 Empire Games. Then there were his world records: 1:48.4 for 800m and 1:49.2 for 880 yards (both in the same 1938 race) and 4:06.4 for the Mile.

This unassuming runner quickly became a crowd favorite. The White City Stadium in London was regularly filled to capacity to see Sydney Wooderson. He thrilled crowds with win after win, posting 14 consecutive victories between 1935 and 1939. The fact that he didn’t look like an athlete—he wore spectacles and appeared emaciated and weak—only added to the crowd’s excitement. One notable youngster who was impressed by Wooderson was Roger Bannister. As a 16-year-old, he watched him run against Arne Andersson in 1945: “Seeing Wooderson’s run that day inspired me with a new interest that has continued ever since.” (First Four Minutes, p. 43) Another schoolboy who was inspired by Wooderson was Olympic Steeplechase champion Chris Brasher.

Much has been made of Wooderson’s stature. He stood at 5ft 6ins (1.68m) and has almost always been referred to as small, often somewhat derogatively from today’s perspective. Contemporary reports in The Times, called him a wonderful little runner, a great little ‘un, a diminutive marvel, a great little runner, a remarkable little runner, a little man, a small bespectacled person. The Associated Press called him a diminutive record-breaker and a shy little fellow. In 1948, even the then Queen referred to him as “Poor little Sydney.”

The widespread belittling of Wooderson’s 1.68m stature reached a comical extreme with the public’s nickname for him: The Mighty Atom. However, he was the same height as his great rival Jack Lovelock—well, one centimeter less—and I can find no similar belittling descriptions of the New Zealander. Milers like Cunningham (1.76m), Ibbotson (1.77m) and Jazy (1.77m) were only a little taller than Wooderson, and a few, like Delany and Hägg were 1.80m. So it’s wrong to think of Wooderson as unusually short for a miler. In fact he was almost exactly the median height for a male Briton of the 1930s.

Though Wooderson was not unusual for his height, he was very unusual for his tenacity. Rarely has track seen a more competitive athlete. With such tenacity, Wooderson rarely lost a race. David Thurlow points out in his Sydney Wooderson: Forgotten Champion, “He was never defeated in a head-on international match for Britain” and goes on to assert “There has never been a better British competitor.” (p. 5) Between 1935 and 1939, his pre-war years as a senior runner, he was beaten only twice—and in one of those two defeats he was lame. Roger Bannister sees this competitiveness as the essence of Wooderson’s greatness: “He taught us that the brain and the heart can be more important that physique.” (“Heroes’ Heroes,” Sunday Times, 28 Nov., 2004)

Schoolboy Champion

|

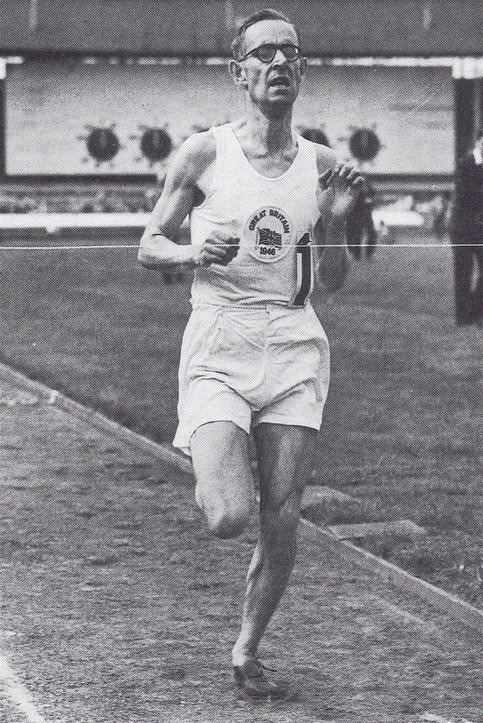

| Wooderson wins the Public Schools Milein 1933. His 4:29.8 time was thefastest ever by a British schoolboy. |

Sydney Wooderson was born in South London in 1914. Like his two brothers he was educated in an independent school in Kent. Sutton Valence School had a cross-country tradition and all three Wooderson brothers excelled. Sydney was the middle brother and early on had to play second fiddle to the older Alfred, who was good enough to place second in the 1930 Public Schools Mile. In the same year, the 15-year-old Sydney was third behind his brother in both the school 880 and Mile. The next year, when Alfred had left the school, Sydney won both races (2:14 and 4:50) and was even second in the 100. More significantly he placed sixth in the Public Schools Mile.

His improvement continued in 1932. He won the 880 and Mile at his school (2:09.4 and 4:54.1) and then ran second in the Public Schools meet, losing by inches with 4:34.4. The Times noted his great effort: “a magnificent challenge by Wooderson, who came from nowhere and would have won had the race been a yard or two longer.” (April 4, 1932) In the same race the next year he became the first British schoolboy to break 4:30 when he won the race with 4:29.8.

City Worker

There were two major changes to Wooderson’s life once he left school. First, he became an articled law clerk in the city of London and began the routine of commuting and office hours. Second, he started to train under a coach, Albert Hill, who had been a double champion (800 and 1,500) in the 1920 Olympics. Hill was the coach for Blackheath Harriers, a club which Wooderson had joined.

After a warm-up Mile in the 1934 Kent Championships (first in 4:27.8, a PB), Wooderson entered his first major championship, the Southern Counties. In the Mile race he was up against the famous Jack Lovelock. The experienced New Zealander, more than four years older than Wooderson, was the current world-record holder of the Mile (4:07.6) and had already competed in an Olympic final. In short, Lovelock, with a time 20 seconds faster than Wooderson, was in another league. But the great man was early in his season and was not expected to be in top condition. Although Wooderson didn’t win the race, he did produce a remarkable final sprint to catch Lovelock at the tape for second place behind Aubrey Reeve. This was a stunning breakthrough both competitively and timewise, for he improved his Mile time by 12 seconds to 4:15.2.

The question now was whether Wooderson could beat the New Zealander again in the British AAA Championships. No one wanted to set the pace and the nine finalists crawled along: 68, 2:21, 3:26. The wily and patient Lovelock waited for Olympian Jerry Cornes to take off at the bell and easily passed him in the last 100. Wooderson, still learning the tactics of miling, also passed Cornes near the finish but could not challenge Lovelock, finishing 1.2 seconds back with 4:27.8. Still, he confirmed that his Southern run was not a flash in the pan. As well, his performance earned him a place on the England team for the Empire Games.

1934 Empire Games

Wooderson’s run in these games was to be his best so far. Still 19 years old, he ran with maturity and courage; The Times called his silver medal “a heroic performance.” (August 8, 1934) He stayed near the front for the first three laps (59, 2:06, 3:12) and then surprisingly took the lead. Cornes passed him at the start of the back straight, and Lovelock managed to slip past him into second before the last bend. Wooderson hung on to Lovelock and moved to his shoulder at the end of the bend. This was enough for Lovelock to make his big effort, and he passed Cornes to win comfortably in 4:12.8. Wooderson had enough strength to pass Cornes for second in a new PB of 4:13.4. No wonder Lovelock wrote highly of Wooderson in his diary: “Wooderson is going to be a great danger in a year or two, when he gains more strength, for he is cool, clever and fast.” (As If Running on Air, p. 149.) In one season Wooderson had graduated from a schoolboy champion to a top international runner.

Two Wins over Lovelock

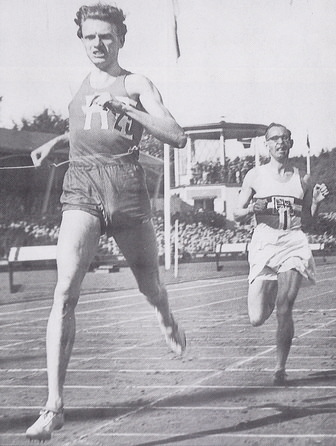

|

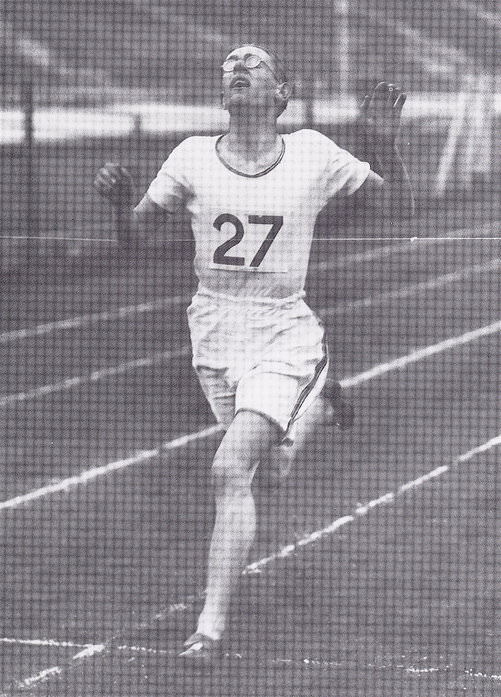

| Wooderson wins the 1936 AAA Milefrom Jack Lovelock. |

After another winter’s conditioning, some cross-country races for his club, and a second place in the Southern Junior Cross-Country Championships, Wooderson was ready to challenge Lovelock again. First he won the Southern Mile, in which Lovelock not competing. He had to wait until the AAA Championships to line up against the New Zealander. Now a wiser tactician, Wooderson didn’t follow the fast early pace (61.0), and was still 8 yards back of the leader at 800 (2:09). Lovelock led at the bell (3:15.4) but soon allowed Wooderson to pass him and stalked him all round the last bend. It looked like Lovelock had the race sewn up, but when he made his effort, Wooderson responded and held him off. He had beaten Lovelock a second time by 7 yards with 4:17.4. This was a sensational win, though some believed that Lovelock was still recovering from his big win in the USA four weeks earlier.

After Wooderson had won a international Mile against France (4:19.0), the two met again three weeks later in Glasgow. This time it was a Mile Handicap with both of them off scratch. Lovelock knew after the AAAs that he had to make the pace fast to negate Wooderson’s finish. After 61.2 and a slow 66.0 second lap, Lovelock felt he had to up the pace and took Wooderson to the bell in 3:11.8. Wooderson waited until 200 to go, and his effort took him well away from Lovelock to a 2.9 second advantage at the tape. It mattered little that the two were third and fourth in the handicap; it mattered more that Wooderson had gained his third victory over Lovelock and set a British record of 4:12.7 to boot. It was a great finish to his season, and he could enter his winter’s conditioning with great Olympic expectations in 1936.

Training

There have been several varying accounts of Wooderson’s training regime. Perhaps the best, and certainly the most thorough, appears in David Thurlow’s Sydney Wooderson: Forgotten Champion. Of course, by today’s standards he did very little training, and in later years he was well aware of this. “Most people today would be shocked at the little amount of training I did,” he told Trevor Frecknall. (“Accidental Hero,” Blackheath Harriers website). Wooderson came at the end of the era when walking was still considered part of a runner’s training.

After his competitive season, Wooderson would rest for a few weeks and then build up slowly with a couple of runs a week over 3-5 miles. Soon he would be up to four to five runs a week as well as competing cross-country for his club on Saturdays and doing a long walk on Sundays. This would continue until the end of March, when for three weeks he would speed up his runs to 5:10-5:20 per mile. He would then begin track training for competition over a Mile. Each session would have a two-mile warm-up and warm-down. Monday: 1320 fast, beginning at 3:20 and progressing each week to 3:08; Tuesday: 3-4x440 in 52-55 seconds; Wednesday: 660 in 1:25; Thursday: 1320 in race time for Saturday; Friday: Rest; Saturday: Race; Sunday: Long walk.

Olympic Year

After suffering from a sprained ankle in the winter, Wooderson began the 1936 season with a brisk 880 to win his club title. It was reported that he was especially working on his speed in the early season. He had no trouble winning the Mile in the British Games (4:16.4). In the next two weeks he won the Kent title (4:27.4) and the Kinnaird Mile (4:20.2), beating Jerry Cornes. The following week he ran much faster in the Southern, winning on the Chelmsford grass track with a British and English Mile record of 4:10.8. To attain this time he had to run the last two laps on his own.

Three weeks later he faced Lovelock for the first time in 1936 at the AAA Championships. It would be their sixth encounter. Laps of 63, 66, and 64 took them to the bell in 3:13. At this point, Wooderson took the lead and stayed there, first fighting off an attack from Lovelock with 250 to go and then holding him off again with 60 to go. Wooderson’s last lap was 62 and his time 4:15.0. He won by a yard. Commentators reckoned that Lovelock had not yet rounded into top form. But had Wooderson? Surely he was also planning his season to peak in Berlin. The press was buzzing with excitement over the showdown to come in Berlin.

Disappointment

However, there was some concern as Wooderson was seen limping after this race. (Times, July 13, 1936) Indeed a photo of the race shows Wooderson wearing a heavy bandage on his left ankle. The Times reported on July 30 that the ankle “may not have answered completely to treatment.” Much later it was announced that Wooderson had turned his ankle in a rabbit hole a month before the Olympics, which meant the accident had happened before the AAAs. Perhaps Wooderson had exacerbated the injury by running this race.

The injury was much worse on August 5, when he lined up for his Olympic heat in Berlin. The official British report on his heat went as follows: “He was limping appreciably…. In the final stretch he tried to drive his unwilling body along faster, but he failed to qualify for the final.” Wooderson was fourth in his heat and needed to place third to qualify. When asked if he could have won the final had he been fit, Wooderson answered: “I think honestly I would not have won. I think the ordeal of the big occasion would have affected me, and my nerves would have got the better of me.” (Thurlow, p. 15) After the Games, Wooderson had an x-ray taken of his ankle and learned that he had a cracked bone.

World Record

With his ankle healed and Lovelock retired, Wooderson’s main opponent in 1937 became the clock. The most glamorous world record was his target: Glenn Cunningham’s 4:06.8 Mile set in 1934. He waited until near the end of the season to attack it. At the end of May he began with a Mile win in the Kinnaird Trophy meeting. The time of 4:17.1 was not remarkable, but his last lap of 57.7 was. His time came down to 4:14.6 when he won the Southern Mile and down to 4:12.2 when he won his third AAA title by 16 yards.

More indication that he would run a very fast Mile came in a very fast international 1,500 win against France in Paris. Wooderson ran the first 1,000 in 3:32, below world-record speed, on his way to a 3:51.0 victory, worth about 4:09 for the Mile. Marcel Hansenne, later to become one of France’s great runners, witnessed Wooderson running for the first time: “How Wooderson could run so fast is a mystery to me, so puny did he appear, but later I learned what a prodigious spirit animated this little man.” (quoted by Phillips, 3:59.4: The Quest for the Four-Minute Mile, p. 107) Finally, after a 4:15.8 Mile victory over a jetlagged Archie San Romani at a packed White City, he focused seriously on records. First he went to Scotland to attack Ladoumègue’s 3:00.6 world record for 3/4 Mile. In a stiff breeze he got very close with 3:00.9. It was a good warm-up for his major attempt on Cunningham’s Mile record.

|

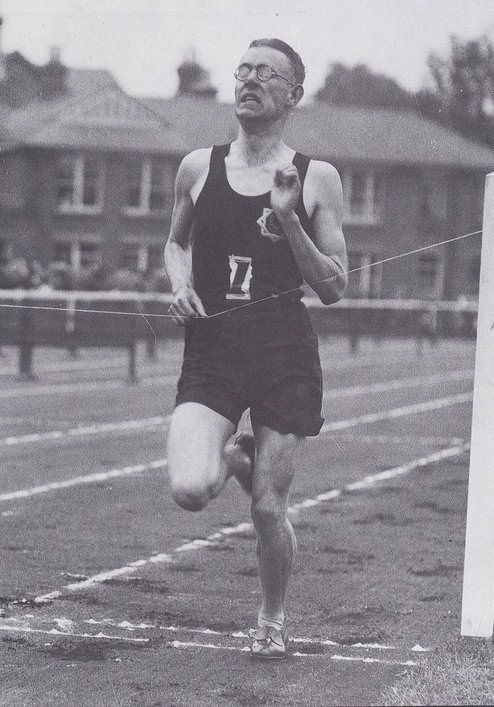

| Setting the Mile world record. |

The 3/4 Mile record attempt had been set up as a handicap, with the aim of giving Wooderson (off scratch) a whole series of runners to chase down. This practice, that had been used by Cunningham indoors, could potentially be helpful, but it often required the record chaser to run wide round bends when overtaking runners. The same type of handicap was meticulously set up for Wooderson’s Mile record attempt at Motspur Park. The track was measured and found to be a fraction short. So Wooderson started an extra 8.3 inches behind the start line.

Reg Thomas, who had helped Wooderson in Scotland, was again the main pacemaker, starting 10 yards ahead in the handicap. The early pace was too fast as Wooderson passed 440 in 58.6 and 880 in 2:02.6. After another half lap, he had to run on his own and overtake a series of slower handicapped runners. He reached 1320 in 3:07.2, thus needing a sub-60 last lap. Some of the runners ahead moved out to give him the inside lane. Wooderson held his form to the tape, passing his younger brother Stanley, who started 140 yards ahead, in the finishing stretch. He covered his last lap in 59.2, passing 1,500 in 3:50.3, and breaking the Mile world record with 4:06.4. He was just 0.4 of a second faster than Glenn Cunningham’s 1934 mark.

The original time given was actually 4:06.6. Of the four watches timing the winner, two read 4:06.4 and two 4:06.6. When one of the 4:06.6 watches was found to be unofficial, the time was amended to 4:06.4, the time taken by two of the three official watches. On hand to congratulate Wooderson, apart from his coach and his parents, was Walter George, 78, the last Englishman to hold the Mile world record, albeit as a professional. George had run a 4:12.2 Mile in 1886.

Law Finals

Following this great run, Wooderson announced that he would be unable to attend the Empire Games early in 1938 as he was due to write his final law exams at that time. Instead, he returned to the more relaxing world of club cross-country races and ran several times for his Blackheath Harriers over the winter.

Obviously his law finals were of prime importance in 1938. Still, he kept up his strict training regime with a view to running well over 880 as well as the Mile. It was reported that above all he wanted to break Lovelock’s 3:47.8 world record for the 1,500. His first race at the end of June was a win in the Southern 880 (1:56.4). The next week he ran a fast 4:11 Mile in a relay. Then he won the 1,500 for Great Britain against Norway (3:58.6) before the AAA Mile. In this race he was a comfortable winner in 4:13.4 for his fourth national title. Four days later he was competing for his club over 440; his 49.3 time showed he had the speed for a good 880.

On July 23 his successful qualification as a solicitor (lawyer) was announced in the press. Now he was able to focus on his running. The results were impressive: one European title, one world record, and an unbeaten record in international competition. The only disappointment was that, despite two valiant attempts (3:49.0 and 3:48.7), he was unable to beat Lovelock’s 1,500 world record.

Success over Two Laps

|

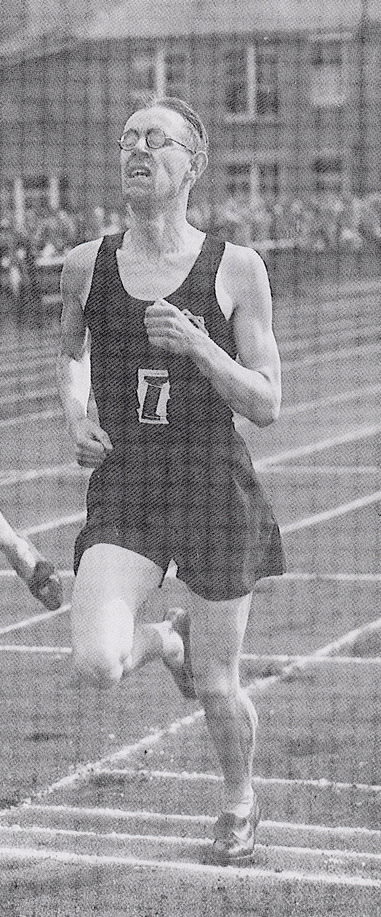

| Breaking the 880 and 800world records in 1938. |

The newly qualified solicitor began his late summer program with an 880 race at the White City against Italian Mario Lanzi, one of the best 800 runners in the world. Lanzi, clearly trying to unsettle Wooderson, started extremely fast. When he passed 220 yards in 25.0, Wooderson was ten yards back. The gap had shrunk to two yards by the bell (53.2). Wooderson clearly controlled the race after this. He stayed close to the Italian until entering the last 100, when he breezed past for a clear five-yard win in a British record time of 1:50.9. It was a fine performance for his first international race over two laps.

His next race was an attempt on the 1,500 world record. This took place at Ibrox Park in Glasgow. Although he got within 1.2 seconds of Lovelock’s mark, his attempt was ruined by some erratic pacing. After a fast 58, he slowed to 67 and then sped up to a 60.4. He needed to run faster than 42.8 for the last 300 but could only manage 43.6. His 3:49.0 was to be the second fastest 1,500 in the world for 1938.

A week later he represented Great Britain against France over 880 and easily beat the French number one, Leveque, with 1:55.8. This set up the major record attempt of the season: an 880 at Motspur Park, where he had set the Mile world record in 1937. Six other runners were carefully set up for the handicap race between 77 and 15 yards ahead of him. The conditions were good. The target was the 1:49.6 world record set by American Elroy Robinson in 1937.

Wooderson began with a 52.6 first lap, about two seconds faster than the average speed he needed. He covered the third 220 in 27.7 giving him 80.3 for 660. To break the record he needed to run faster than 29.3 for the last 220. And although he did slow, he managed to run 28.9, passing 800m in a world record 1:48.4 and 880 yards in a world record 1:49.2. Wooderson, the great competitor, was now breaking records as well as winning races.

European Champion

Two weeks later he lined up in Paris for the 1,500 final in the European Championships. This turned out to be one of his easiest races of the year. His main challengers were Beccali of Italy and Mostert of Belgium; neither of them pushed him. In windy conditions, a confident Wooderson stayed in the pack until the bell, when he moved to the front. Once in the lead, he ran just fast enough to keep the field at bay, looking back several times to ensure he was well clear. Only Mostert was able to make any kind of challenge. Wooderson won in 3:53.6, with Mostert second in 3:54.5. This was Wooderson’s first major title. “I think to a certain extent the others were a little afraid of me,” he recalled much later. “So that was why I won, as I don’t think I was quite at my best at the time.” (Alastair Aitken interview,1979, Highgate Harriers website)

He had two more wins in his 1938 season. In Milan he again beat Beccali 3:58.4 to 3:58.8. Then he ran his fastest 1,500 in Oslo, this time defeating his other main European challenger, Mostert. After laps of 61, 61.5 and 63, he ran the world’s fastest time of the year with 3:48.7, just slower than Lovelock’s 3:47.8 world record. This was a fine run to end what was probably his best-ever season.

American Adventure

It’s not difficult to surmise what goals Wooderson and his coach had planned for the next two years. Clearly, after the unfortunate ankle injury had ruined his hopes in Berlin, the major goal was the 1940 Olympics. Unbeaten for two years and fresh from his European triumph, he must have been really confident about winning a gold medal. As for the upcoming year, the 1,500 world record, which he had tried to capture in 1938, must have been at the top of his list. There was also the challenge of running the Princeton Mile against the Americans.

Possibly because he was now a practicing solicitor, he does not appear to have run cross-country in the 1938-9 winter. After committing to race the Princeton Mile in early June, he began his competitive season early, running 4:14.8 in an interclub meet on May 1. Two weeks later he won the Inter-Counties Mile by nearly 12 seconds in a remarkable 4:07.4. It was his second fastest Mile. This run was all the more remarkable because it was a solo effort. Instead of relying on his finish, Wooderson went straight to the front and reeled off laps of 61, 64, 63 and 59.4. Clearly he was in condition to break his world record. A week later in Birmingham he ran 4:12 and then, just before sailing to the USA, he beat his record for 3/4 Mile with 2:59.5.

|

| Wooderson (28) is forced almostoff the track by Rideout. Note that he is stepping on the rail. |

But his only American race was not a success. Wooderson was to learn, as Americans had done when coming to race in Europe, that it was not possible to run well after a six-day transatlantic sailing. It was not so much the training days lost as it is the acclimatization to a new environment and the five-hour time difference. Thus he was not his usual feisty self when he lined up (in his Blackheath club vest) with his four American opponents, Glenn Cunningham, Charles Fenske, Archie San Romani and Blaine Rideout.

But before his race Wooderson had an interesting appointment with a retired Princeton professor, Joseph E. Raycroft, who had been the Director of College Health and Athletics. In a physical examination, the following details emerged: weight 120lbs; height 5ft 6ins; heart rate 56; chest 31 1/2ins expanded 34 1/4ins; stride 6ft 2ins to 6ft 6ins. There were also general details: likes ice cream, plays tennis and golf, prefers fish to meat, drinks milk on going to bed; hikes 30 miles on [Sundays]. General rating: good but not too good for a world champion. (Boys’ Life XXIX:9, September 1939)

Princeton Mile

As the 1938 Princeton Mile got underway, Wooderson surprisingly went straight to the front. Even more surprisingly he did not push the pace. Surely, setting a fast pace would have been the only reason for leading. He led through laps of 64, 64, 66 to reach the bell in 3:14. Down the back straight Rideout twice tried unsuccessfully to take the lead. Coming into the last bend, the Americans closed right up and Rideout again made a desperate bid for the lead. Wooderson’s resistance forced him to cut in early and he forced the Englishman to step on the curb and lose his balance. As Wooderson tried to regain his temp--he was described as “out of sync and disoriented (Paul J. Kiell, American Miler, p. 292)--the Americans all rushed past him and left him to finish last. Fenske won in 4:11.0; Wooderson’s time was 4:13.

The referee was consulted, but he let the result stand, saying that the impeding had been unintentional. An overhead photo shows Rideout and Wooderson side-by-side but not quite touching, and Wooderson with his foot on the curb. Rideout’s left shoulder is about one foot from the curb, so Wooderson had no room to continue forward. At first Wooderson claimed an infringement: “I was fouled…. Rideout cut across in front of me and forced me onto the rail.” (Milers, 127) But after he had calmed down he was more diplomatic. “We were bunched, which was natural enough,” Sydney graciously said later. “Rideout did not touch me as he went by. He was so close that in trying to avoid him I hit the rail and stumbled.” (Thurlow, p. 27) Rideout tried to justify his actions: “Wooderson was a beaten runner when I passed him. I cut in too quickly, I’m sorry.” (Milers, p. 127) Cunningham, who was running behind Wooderson, saw what happened. “But I don’t want to say anything,” he said. (Kiell, p. 293) Some post-race opinions concluded that Wooderson was not quite 100% for this race, and that he would have been able to resist Rideout’s attempt to pass had he been his normal self.” Joe Binks, for example, wrote, “Sydney just wasn’t himself today.” (Milers p. 128)

Wooderson came home a disappointed man but went straight back to his winning ways, taking the AAA Mile for the fifth consecutive year in 4:11.8, though he was hard pressed by Denis Pell (4:12.0) and needed a 57.8 last lap to win. A good win in Brussels over Mostert (3:54.8) followed. Then while running a Mile in Newcastle (4:15.2) he developed an injury that ended his season prematurely and put an end to any attempt on the 1,500 world record. Soon he was to discover that his career might well be over as the world war started two months later.

Wartime

For the next six years, with his country at war, Wooderson still managed to keep in shape. “I used to keep up my running,” he told Alastair Aitken, “but of course on very bad tracks and [with] very little competition. I could not train properly.” (Highgate Harriers website) He managed to race, often contributing to the war effort by entertaining large crowds of spectators and raising money. Jack Crump in Running Round the World recalls Sydney once traveling all night in the corridor of an overcrowded train to compete in a Scottish War Charities meeting in Glasgow: “The train arrived several hours late and about three hours before his race. We managed a meal for him, for he had had no breakfast, and contrived to get him a couple of hours’ sleep…. He made no complaint and arrived for the start of the special mile-handicap race. It was a terrible afternoon, very wet and with half a gale blowing.” (pp.78-9) His poor eyesight had precluded him from military action, but he still served on the home front. First he joined the National Fire Service, which was arduous work during the London Blitz. Later he served in the Pioneer Corps and then with REME (Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers).

In view of wartime conditions and the lack of good food, it’s surprising how fast he was able to run the Mile in the war years: 1940, 4:11.0; 1941, 4:11.2; 1942, 4:16.4; 1943, 4:11.2; 1944, 4:12.8. Over the 1940-1945 war years, Wooderson ran 14 cross-country races and 47 track races. (Andreas Janssen, Great Distance Runners website) He maintained good health until 1944 when he developed rheumatic fever, which particularly affected one leg. Hospitalized for four months, he was told his running career was over. But as soon as he was discharged he began jogging. Six months later he ran a Mile in 4:25.

Mile Races Against Andersson

With the war over, two races were set up for Wooderson against Arne Andersson, one of the two great Swedish runners who had been breaking world records over the war years. On the face of it, these races would hardly be competitive. While Wooderson had been training intermittently for six years, eating poor wartime meals and racing only exhibitions, Andersson had been living, training and racing under ideal conditions. As well, Andersson had run the Mile five seconds faster than Wooderson, whose best was now eight years in the past.

Their first encounter was at the White City. Such was the interest that thousands of fans were shut out when the stands became full; such was the interest that two gates were pushed down, allowing thousands more to cram into the stands. The attendance was officially 54,000, a record. From the gun, Andersson went straight into the lead and stayed there until the bell, when to the roar of the crowd Wooderson nipped into the lead. The lap times, 60.8, 62.4 and 65, showed that Andersson had slowed the third lap. Perhaps that is why Wooderson decided to move ahead. He was criticised for this move, but he must have been wary of the younger man’s speed.

Buoyed by the roar of the partisan crowd, Wooderson led all the way to the final straight, but he could not hold off Andersson’s late challenge, the Swede winning with 4:08.8 to Wooderson’s 4:09.2. Everyone agreed that Sydney’s performance was magnificent in the circumstances. And his time on a very poorly maintained White City cinder track was his best since 1939.

|

| Andersson finishes ahead of Wooderson inGothenburg in their second 1945 Mile race. |

The return race just over a month later in September, saw Wooderson in even better form. In the intervening week, he had scored a fast 3:48.4 victory over Marcel Hansenne in France. The Swedes decided that a fast pace was needed to beat Wooderson, so Isberg was designated to run a fast first half. After he passed 880 in 2:00.1, Andersson took over with Wooderson at his heels. The pace dropped a little, 3:02.8 at the bell. This time Wooderson waited until 200 to go for his effort, and he got by despite Andersson’s effort to deny him the lead. He was still ahead with 70 to go, and Andersson had to make a supreme effort to catch him and win the race.

There was physical contact as Andersson drew level, as witnessed by British team official Jack Crump: “Andersson made a desperate effort 50 yards from the finish with his arms flailing, and his left arm caught Sydney, flung him half around and almost stopped him in his tracks. It was, I am sure, a pure accident, but I am just as certain that it cost Sydney the race.” (Running Round the World, p. 83) Crump heard some booing from the Swedish crowd after the race and noticed that Andersson was “quite upset by the incident.” Shades of Princeton. Still, he had run an incredible 4:04.2, his fastest-ever Mile, and he had pushed Andersson to his limit. Has there ever been such a competitor?

Preparing for the European Championships

His 1945 season ended abruptly through an achilles injury. Realising that his achilles was now a chronic problem, Wooderson decided that to keep running he would have to move up to longer distances. No more Half-Miles and Miles. This move up required alterations to his training. Over the winter he increased his runs to seven miles and lengthened his Sunday walks up to 15 miles at times. On the track he would run 1.5 to 2 miles three times a week and 2x1320 once a week.

Before his first serious 1946 race on July 22, he won three minor races: the Kent 3 (14:59.2), a Two Miles in Dublin (9:34.4) and an inter-club 3 (15:00). This was a gentle warm-up for a very competitive Three Miles in the AAA Championships against the Dutch star Willem Slijkhuis. It quickly became a two-man race as Wooderson took the lead on the fourth lap. Dogged lap after lap by the smooth-running Dutchman, Wooderson went through one mile in 4:40.6 and two miles in 9:23.4. With 300 to go, Slijkhuis burst ahead dramatically. He was clearly anxious as he looked back a couple of times before Wooderson, to the roar of the 25,000 crowd, caught him at the crown of the last bend and then sprinted past with 100 to go. Slijkhuis did not give up easily and was only three yards behind at the tape. Wooderson’s 13:53.2 broke the British record set by Maki in 1939 by more than six seconds. His last lap of 58.4 was very fast for a three-mile race.

His confidence boosted by his first major race over the longer distance, Wooderson had one more three-mile race before the European Championships. His main opponent, Pujazon of France, a fine steeplechaser and harrier, but not a top-class track runner. Wooderson won easily in 13:57.

European Champion Again

On August 23, Wooderson lined up for the European 5,000 in Oslo. Also on the starting line were Slijkhuis; the Finnish champion Heino, who owned the 10,000 world record and had already won the 10,000; a fast-improving Belgian, Gaston Reiff; Nyberg of Sweden; and a relatively unknown Czech, Emil Zatopek. There was no doubt that Wooderson had the ability to win—though Slijkhuis was the favorite—but he was still relatively inexperienced over this longer distance.

|

| 1946 European 5,000 final.Wooderson (left)is in control as Viljo Heino tries to hold him off. Gaston Reiff, the 5,000 Olympic champion in 1948, is on the inside. |

As expected, Heino and Reiff tried to take the sting out of Wooderson (and Slijkhuis) by making the early pace fast. Wooderson, showing great confidence, was not sucked in by this tactic and was content to run the first mile at a more sensible pace between sixth and tenth. Heino, Reiff, Slijkhuis and Pujazon were at the front. At around the eighth lap, Wooderson moved into the lead, but soon dropped back to fourth. It’s not clear why he did this; perhaps he was testing the other leaders. As the pace slowed he moved to where he wanted to be—on the shoulder of Slijkhuis.

At 1,200 to go, Slijkhuis moved into the lead; Wooderson was ready and went with him. It was now a two-man race. Wooderson bided his time, making his effort before the last bend and earning a five-second margin at the tape. Within a few days of his 32nd birthday, Wooderson thus won his second European title in 14:08.6. With a 61 last lap he had run the second fastest 5,000 ever and had eclipsed the British record by 23 seconds. No wonder Wooderson regarded this race as his most satisfying. No wonder he collapsed after breaking the tape.

He had worked out his own pace for the race based on a winning time of 14:10. The plan was for Jack Crump, the team manager, to shout out whether he was on schedule. With the noise of the Oslo crowd, he couldn’t hear Crump at all. “I knew however that the pace was fast,” he said afterwards. “I was content to lay well back whilst some of the others fought out the lead. The pace slowed perceptibly on the tenth lap, and I was just contemplating going up when Slijkhuis took the lead. Not long after he made his effort, determined not to leave it so late as at the White City, in an endeavour to kill my sprint, and I must admit he made it uncomfortable enough for a while.” (Thurlow, p, 41)

He was perhaps a little lucky that his nagging achilles held out, for it had been giving him a lot of pain. In fact, a week later it did break down when he ran before 5,000 spectators at Motspur Park in an attempt on the British record for Two Miles. He was well on schedule to beat the 9:03.4 mark, passing the halfway distance in 4:26.8, but on the sixth lap he started limping. And although urged to stop, he managed to still finish with 9:12.8 and win. His reason for continuing to run was that it was a team race and he wanted to earn points for his club.

No More Track Running

In the 1940s surgery was not an option for curing a chronic achilles problem, so retirement would have been an obvious choice at this time. Not for Wooderson. It seems that he could still run provided he did not get right up on his toes and sprint. With this reality in mind, he announced that he would not compete in the 1948 London Olympics and turned instead to cross-country as an alternative to track racing. Within 10 weeks of his Two Mile race he was running for his club over the country. He was eighth and third before he won a race. Then in 1947 he placed fifth in the Southern and seventh in the National championships.

He was back competing over the country in early 1948, winning the Kent title and placing third in the Inter-counties. Clearly in better shape than in the previous year, he won the Southern title by ten seconds. The National race was next. This race was held over 10 miles at that time; it was therefore quite a different race from his track events, not only in distance but also in terrain and weather conditions. The Sheffield course was described as hilly, but judging by the photos of the race it was not too muddy.

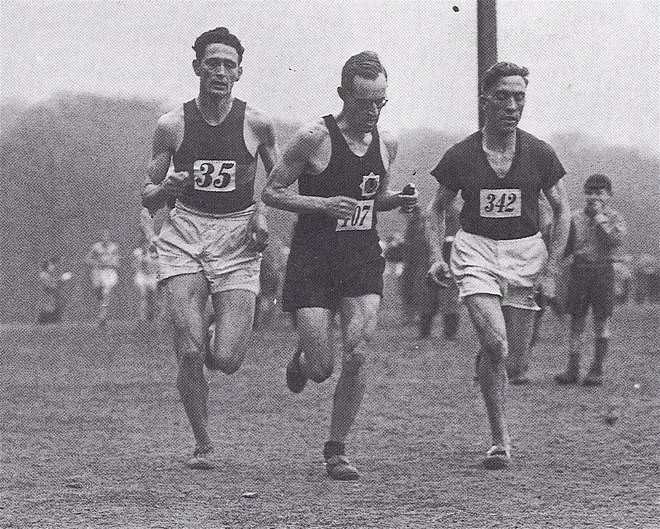

|

| 1948 English Cross-Country Championships. Wooderson(centre) fights it out with Vic Blowfield (35) andAlbert Horrocks (342). |

When the field thinned out, there were four in a bunch at the front, including Wooderson. He was up against two cross-country specialists, Vic Blowfield of Belgrave Harriers and Albert Horrocks of Halesowen. Both these harriers knew that they had to break Wooderson before the last half-mile, but they were unable to do so. Sydney said afterwards, “It was really an effort and the mental strain of cross-country running was bad, as one was wondering all the time whether one was able to last out.” (Thurlow, p. 48) As usual Wooderson was up to the task, and he managed to open up a small gap to win in 56:52, four seconds ahead of Blowfield and nine ahead of Horrocks.

His 1948 Nationals win was his last great performance. This win put him in the England team for the International Cross-Country Championships three weeks later. But he hadn’t fully recovered and placed a respectable 14th. He competed in one more cross-country season, placing fourth in the Kent championships and 52nd in the Nationals. Then 15 years after his first appearance on the national scene, he retired.

Almost everyone had expected him to be the runner carrying the Olympic torch into the stadium for the opening of the 1948 London Olympics. The Times leader said the day before the Games were to open, “Nearly everyone knows the runner they would like to see.” (July 28, 1948) Sadly Wooderson was passed over in favour of a young quarter-miler called John Mark. Wooderson had been told earlier that he was to carry the torch to light the flame and arrived at Wembley Stadium expecting to do this. At the last moment he was told he was not going to be the torch carrier. This whole sorry affair is thoroughly described in The 1948 Olympics: How London Rescued the Games by Bob Phillips.

Conclusion

To call Sydney Wooderson beloved might seem a little extreme, but there has rarely been an athlete that the public has taken to with such devotion. Part of his appeal was that he looked like a normal bloke. Thus people could easily identify with him. Then there was his tenacity which George Smith called “the ferocity of a tiger.” (All out for the Mile, p. 74) This tenacity made his races such a spectacle. If he was in a race, crowds would flock to see him.

|

|

Wooderson meets Walter George, who set a Mile WR in 1886 (4:12 3/4) |

His modest personality also endeared him to many people. Jack Oaten, a journalist who knew Wooderson well, aptly called him “meek.” He was generous and loyal; these qualities were most apparent in his dedication to his club, Blackheath Harriers: “Never was a member so beloved by his club-fellows, and never did an athlete prove a better teamsman to his club.” (George Smith, p. 74)

Modesty and shyness made him a very private man who avoided interviews whenever he could politely do so. And he was never one to impose his thoughts on people through writing—an exception being a short booklet on running. This is a shame, for he was clearly an interesting person with a rich mind. So it’s unlikely that we will get an in-depth biography of Wooderson. So far the only biography has been David Thurlow’s wonderful Sydney Wooderson: Forgotten Hero, which focuses entirely on his running; it’s “a simple record of the man’s achievements on the track,” as John Rodda puts it. (Guardian, Dec. 20, 1989) Wooderson was in Thurlow’s words “an ordinary chap, a bespectacled solicitor who went to work with his umbrella on the train from South London to the City every day and ran as a hobby.” Thurlow, p. 5) But there was surely a lot more to this private man. How to explain, for example, the two contrasting sides to his personality, the “tiger” on the track and the meek and mild citizen?

Footnote

When Wooderson retired from his legal work in the City of London, he moved to the rural area of southwest England, settling first in Devon and then in Dorset. He kept fit, walking regularly well into his eighties. He did occasionally make public appearances. On one such occasion he joined other Mile world-record holders in London for a 50th anniversary celebration of the first four-minute Mile. Almost 80, he was the oldest living record-holder of the 14 greats assembled. Twelve years later Sydney Wooderson died in a nursing home at the age of 92.

1 Comment