Profile: Harald Norpoth

b. 1942

Beginnings

Between 1964 and 1973, Harald Norpoth was a dominant force in international middle-distance running. Combining stamina with a punishing finishing kick, he won more than three-quarters of his outdoor track races. Although he never won a major championship, he was universally respected as a 1,500/5,000 runner. A three-time Olympian, his best performance was 2nd in the Tokyo 5,000 in 1964. However, he also ran extremely well in the Mexico 1,500 (fourth) and the Munich 5,000 (sixth). On the European scene, he won gold medals in three consecutive European Cups and in the European Championships he won one silver and two bronze medals. Although more of a racer than a record-beater-- "I was more the competitive type”--he did set a WR for 2,000 (4:57.8) and European records for 5,000 (13:24.8) and 3,000 (7:45.2). Norpoth once received a telling compliment from another great competitor of his era, Ian Stewart: “I respect him even more than Ron Clarke. Some think Clarke’s the be all and end all of running. He’s bloody good. But as a racer I’ve got to go for someone like Norpoth.” (The Times, Oct 24, 1969)

Norpoth grew up playing football, but by his late teens it was clear that he had a special talent as a runner. His first success came a month before his 18th birthday when he won the 3,000 German Youth title in 8:36. His other best times for 1960 were 1:56.5 and 3:55.6. The next year saw great improvement as he appeared in the world rankings with a 3:45.0 for 1,500. This time was achieved when finishing third in the German Senior Championships. Three weeks later he was second in the German Junior Championships with 3:54.6.

In 1962 Norpoth won his first German 1,500 title with 3:42.8. This qualified him for the European Championships at just 20 years of age. He made the 1,500 final (second in his heat behind Jazy in 3:48.0), but he fell just before the bell and finally dropped out when he realized the situation was hopeless. Despite this setback, he managed to set a German 1,500 record late in the season with a 3:41.2 victory over his German rival Eyerkaufer. This time ranked him ninth in the world for 1962.

Winning Ways

|

| 1963. On his way to a 5,000 victory over Tulloh (in lead)and Hill (left) |

After such a rapid rise to national level, Norpoth’s performances leveled out in 1963, his fastest 1,500 being 3:42.8. But he raced often, gaining experience and developing tactical skills. Out of 18 races, he won eleven; most losses were to very good runners--three to Michel Jazy and one each to Salonen and Baran. One significant change in his 1963 season was that he began to race at 5,000. His best time in five attempts was 14:03.6, which placed him 49th in the world rankings.

His modest times over 5,000, though promising, did not suggest that he would be up with the world leaders in 1964. But prior to the Olympics he improved his 5,000 time by 15.2 seconds to 13:48.4 when finishing second to Ron Clarke (13:41.0) in Berlin. This was a new German record. Perhaps his focus on the 5,000 was the cause of his failure to make the German Olympic team at 1,500. He finished only fourth in the trials, despite having won the German National title (3:41.6) two weeks earlier. Nevertheless, he did win the 5,000 trial in 13:54.4. So he went to the Tokyo Olympics not as a 1,500 runner but as a 5,000 runner.

Tokyo 5,000

|

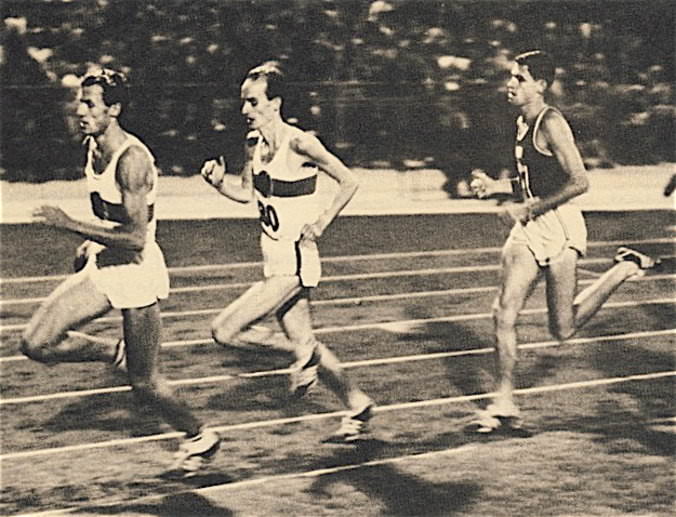

| Jazy makes his bid on the back straight. Norpoth and Schul try to pull him back. |

His impressive 13:48 German record still did not make Norpoth a medal favorite. Earlier in 1964, three runners had gone under 13:40 and another eight had run faster than Norpoth’s 13:48. The best thing going for him was his emerging competitive ability and his good finishing kick. He was lucky to be in the slowest of the four heats, so he qualified comfortably in third place (14:11.6). Most of the other finalists had to run about 20 seconds faster to qualify. With only 48 hours between the heats and the final, this might have given him an edge.

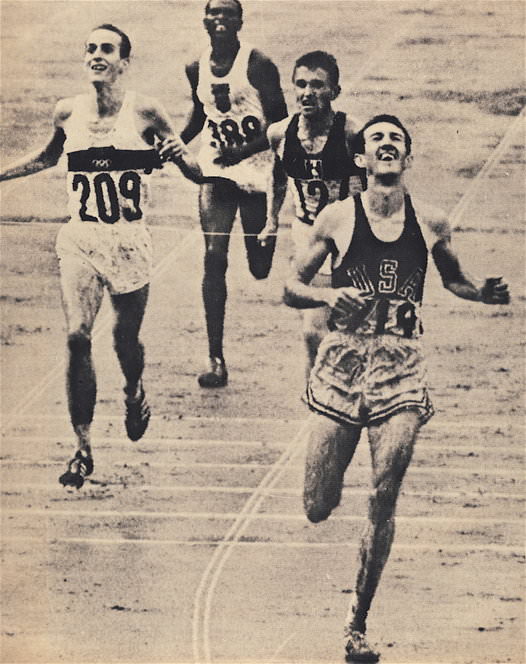

|

| 100 to go: Jazy tightens up and Schul passes Norpoth. |

The final started in heavy rain. After two slow laps, Ron Clarke started to push the pace with surges. Norpoth was always in close attendance, as was the race favorite Jazy. Perhaps Norpoth used a little too much energy doing this, but he clearly wanted to ensure he was right there for any substantial break. Americans Schul and Dellinger, in contrast, took a risk by not responding immediately to Clarke’s surges. They sometimes lost contact with the leaders, but on the other hand they did conserve energy by running at a steadier pace.

|

| The finish: Norpoth raises his arms for a personal victory as Schul wins. |

Despite Clarke’s surges, there were still nine in the leading group with 800 to go. Norpoth always made sure he was in the top three. When Dellinger surged into the lead with 600 to go, Norpoth moved with him and stayed in third. He wasn’t quite as quick to respond to Jazy’s move round the penultimate bend, waiting instead until the back straight to move up to second. This move appeared to be quite easy for him, and he looked like he had the beating of everyone except Jazy. He was 4-5m behind the Frenchman when he moved into second and kept that gap the same until 200 to go. Round the final bend he had the inside and made up a little on Jazy, but Schul came up to his shoulder and was past him soon after the crown of the bend. When Schul passed Jazy with 70 to go, Norpoth was still 2m behind. But Jazy was tying up badly, so Norpoth was able to pass him for the silver medal. The look on his face as he realized he had come second shows how pleased he was. Indeed his body language seemed to say he had won.

Training

Norpoth had gone from a promising youth to an Olympic silver medalist in five seasons. Clearly he was training effectively. His coach was Ernst Van Aaken, a doctor who specialized in Sports Medicine. Van Aaken’s method differed considerably from that of his more famous countryman Gerschler. His principles can be summed up in his often quoted prescription: “Run long, run daily, drink little and don’t eat like a pig.” In 1947 Van Aaken published Running Style and Performance which explained his “pure endurance method.” Focusing on aerobic training, he believed that the goal of training was to increase the size of the heart in order to get more oxygen to the cells. Norpoth is generally considered to have been Van Aaken’s most successful runner. He definitely followed Van Aaken’s “run daily” prescription: “On 365 days a year I trained outside, whether rain or snow, minus 25 degree weather,” he has said. As well, judging by his emaciated physique, it seems probable that Norpoth followed the minimal eating requirement. For someone 6 ft 2 (1.85) tall, his weight of 60 kg. was certainly extremely low. However, it is not quite so clear how closely he followed Van Aaken’s ideas on running long and slow.

Van Aaken was not of the LSD school. He did employ interval training, but he didn’t want his athletes to run fast. Van Aaken himself has said of Norpoth, “I had to teach him to run slowly.” (1975 Interview posted on Letsrun) Some of Norpoth’s training logs have been published, but these are all from the competitive season when he was not training hard. None of these logs show him running faster than his 1,500 racing speed. Van Aaken’s requirement that his athletes never get into oxygen debt was apparently followed by Norpoth in these published logs.

|

| Norpoth's coach Ernst Van Aaken. |

While Norpoth’s winter conditioning has remained undocumented, there is some indication that he did occasionally go into oxygen debt during the winter when he competed indoors and on the country. He competed indoors every year from 1961 to 1973 except 1964, averaging 3-4 races a year, just enough to get his legs moving at race speed. And he was successful indoors, winning a European championship over 3,000 in 1966 and earning four 1,500 German titles. As for cross-country racing, he participated once or twice a year. He raced four times over 10,000 in the 1960s, winning the German title once and coming second on two other occasions. But he clearly preferred the shorter cross-country distance of around 3,000. He won the German title at this distance six times between 1964 and 1972. But how did Norpoth develop his often unanswerable kick? Although Van Aaken prescribed some 50m sprints, surely these would not have been enough to develop his sprinting speed. It has been claimed that Norpoth’s strong heart gave him the ability to sprint at the end of a race because he was less fatigued than his rivals. The same has been said for Peter Snell, but the New Zealander clearly had better innate speed and has been documented as having done a lot of speed and hill work before the competition season. It would be helpful to ask Norpoth for specifics of his winter conditioning and for confirmation that he really never trained into oxygen debt. Van Aaken has said that 90% of Norpoth’s training was done with his pulse between 120 and 150, and that the other 10% never pushed his heart above 180. It is hard to believe that a 1,500/5,000 international runner could achieve success on such a gentle training regimen.

Competitive Success

The confidence that he gained in the Tokyo Olympics began to show the next year. In 1965 Norpoth won his first of three gold medals in the European Cup. Taking charge of the race in the penultimate lap, he gradually dropped all of the field except Witold Baran and Derek Graham. These two were still close to Norpoth on the back straight, but they could not match his strength over the last 200. 1965 also saw Norpoth break two German records with 7:55.2 and 13:42.8 for 3,000 and 5,000. As well, he reduced his 1,500 time to 3:39.8.

|

| Norpoth follows Jazy in a match v. France. |

Norpoth’s 1966 season was even more successful. He was in the best form of his life, so it was unfortunate that this coincided with Michel Jazy’s peak years. The brilliant Frenchman beat him in both his races at the European Championships. Norpoth competed a lot in the early season, racing six times over 1,500 and three times over 5,000.

In July he won the German 5,000 title (13:50.4) before moving on to the European championships. In the 1,500 final he led the field at the bell with his team-mate Bodo Tümmler. Close behind was Jazy of France. The three were close together in the last 100, but Norpoth faded as T¨mmler surprisingly came through for the win (3:41.9). Jazy barely got by Norpoth for the silver medal, both runners being given the same time of 3:42.4. Three days later, Norpoth went all out for a victory in the 5,000 with an uncharacteristic tactic. He took the lead with 500 to go, the 4K mark having been passed at 14:03 speed. Norpoth’s effort was too much for everyone except Michel Jazy, who patiently waited until the last 80m to make his effort. Norpoth was unable to respond, exhausted from running the last K at 2:30 speed. At the tape he was 1.2 seconds behind Jazy and 3.8 seconds in front of third-place finisher Diessner. So although Norpoth came away with a silver and a bronze, he must have been hoping for even better results. But there were more good races to come.

Taking advantage of his form, he ran a new European and German record for 5,000 (13:24.8) ahead of Girke, Billy Mills and Philipp. This was a 16.6 second improvement. Only Ron Clarke (13:16.6) ran faster in 1966. And three days later he ran a 2,000 WR ahead of Bodo Tummler with a 4:57.8, a huge breakthrough for this event. He smashed the previous WR of 5:01.2 by 3.4 seconds and was the first through the 5:00 barrier. Then, after a 3:39.7 1,500 PB behind Tummler in a match against Poland, he ran a 1,000 PB in 2:17.3 behind Kemper’s WR-equaling 2:16.2. With two European medals, a World Record and a European Record, Norpoth’s 1966 season had been the most successful so far.

|

| Tummler and Norpoth lead Jim Ryun in a West Germany v USA meet. |

The next year was lower key. His best 5,000 was only 13:41.2, although yet again this was a first-place run. Further, his season’s best of 3:42.5 did not get him into the top 20 of the word rankings for the 1,500. Norpoth’s biggest competitive success was in the 5,000 in the European Cup held in Kiev. In an extremely slow race, Norpoth used his speed to beat the 10,000 winner Jurgen Haase by one second in 15:26.8. Later he set a European record for 3,000 with 7:45.1, a time he never bettered. Finally, in what was really a rehearsal for the Mexico Olympics 1,500, he and team-mate Tummler came up against Jim Ryun in a match with the USA. With all three having fast finishes, the last lap was expected to be exciting. Running as a team, the Germans tried to outfox Ryun. When Tummler took the lead at the bell, Norpoth, I second place, tried to make it difficult for Ryun to follow his team-mate. He forced the American to run really wide round the penultimate bend. But Ryun caught Tummler with 300 to go. The American’s last 300 left two of Europe’s finest finishers languishing far back. At the tape, Ryun (3:38.2) had taken four seconds out of Tummler (3:42.3) and Norpoth (3:42.5) with a last 300 of 36.4. In fact, Norpoth barely held off the second American, Grelle (3:42.8). It was a sobering end to the season.

1968

Norpoth began his 1968 track season in late May, five months before the Mexico Olympics. He ran low-key races over 800 (1:51.5) and 1,500 (3:43.8, 3:43.8) before teaming up with Kemper, Adams and Tummler for an attack on the 4x880 WR. Their attempt was successful with 7:14.5, Norpoth’s leg being a speedy 1:48.5.

A few days later he was a lowly seventh in an international 5,000 in Stockholm won by Lajos Mecser. His time of 13:35 was acceptable, but he had never finished so low in a race (his next lowest was fifth in the 1970 European Cup Final). But two days later he bounced back with a German Record for Two Miles in 8:25.6 ahead of Ron Clarke. Up to the National trials in the middle of September, he ran three low-key races over 1,500 and came second in the 5,000 in a six-country international meet.

Following a comfortable 14:05 victory in the German trials, he was selected for both the 1,500 and the 5,000 for Mexico. During some of the six weeks leading up to the Olympics, he was in Flagstaff, Arizona, for some altitude training. During this visit he won a 3,000 race in 8:21.6 in front of American Kenny Moore.

1968 Olympics

|

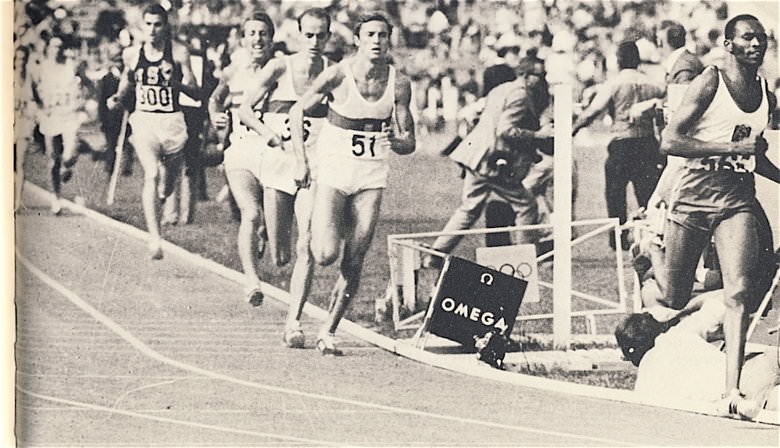

| Mexico 1,500: Running with Jipcho, when the rest of the field chooses to run at a more even pace. |

After a comfortable 14:20.6 third place in his 5,000 heat, Norpoth developed stomach trouble. He was not well for the final, but lined up all the same. The slow initial pace enabled him to stay with the field for eight laps but then, according to Track & Field News, “he stopped and rubbed his stomach. Hesitantly he resumed running, but a few yards later retired for good.”

By the time the 1,500 heats came around, his stomach was better. The heats and semifinal were run without any problems. In the final Norpoth had to deal with Ryun, Keino and Tummler. On paper he was not one of the fastest six finalists; nevertheless, he ran to win from the start. They were brave tactics, but perhaps foolhardy. When Kenyan Jipcho blazed off at a very fast pace, Norpoth was the only one to go with him. At 200 Jipcho and Norpoth already had a few yards on the field. However, just before 400, Keino and Tummler had moved up, and soon after the 56.0 first lap was called, these four runners opened up a gap on the field, with Norpoth still in second.

|

| Mexico: Chasing Keino with one lap to go. Tummler leads Norpoth and Whetton, whlle Ryun is moving up fast. |

With just over two laps to go, Norpoth was still tucked in behind Jipcho. But then Keino just burst into the lead. Tummler and Norpoth immediate changed gears and went after Keino, who passed 800 in 1:55.3. But the two Germans, now joined by Whetton, were unable to hold on to the Kenyan. At the bell he was seven yards up on Tummler, who was closely followed by Norpoth. At 1,200 the two Germans were still together but now over 10m behind Keino. Meanwhile Ryun, in full flight down the back straight, moved past Norpoth and up to Tummler’s shoulder before the final bend. Norpoth, who had been running close to Tummler, began to drop back. He was now out of the medals and had to hold off John Whetton. He did this with a clear 1.3-second margin for fourth place and a 3:42.5 time. It was a fine run, but he was 3.5 seconds out of a medal. He had run a brave race but had lost to three much faster 1,500 runners: Keino (3:34.9), Ryun (3:37.6), Tummler (3:39.0). Even if he had begun more conservatively, he would still have not been able to make up such a huge gap.

1969

At 26, with two Olympics behind him, Norpoth still had ambitions. The European Championships were his main objective in 1969. Unfortunately he was unable to compete because of a boycott by the West German team over the eligibility of Jurgen May, who had recently defected from East Germany. This letdown led to a quiet competitive year.

His year started well with a second place in the 10K German Cross-Country Championships behind Lutz Philipp. In June, he joined Adams, Tummler and Kemper to record the third fastest 4xMile Relay ever; his contribution was a 3:58.9 mile in a 16:09.6 team effort. In July at Stockholm, he ran his fastest 5,000 of the year (13:36.0); however, he was beaten into third by Jurgen May (13:33.0) and Ron Clarke (13:33.8). His best 1500 was run in Eschweiler, where he beat Dumon and de Hertoghe in 3:41.9. Disappointed over the German boycott of the Euros, he ended his season ended early on August 17 after winning the German 5,000 title in 14:18.2.

1970

After the letdown over the Euros, Norpoth bounced back with some excellent racing in 1970. He not only won the European Cup final but in different races also beat two of the most competitive runners in the world. His preparation for the European Cup began with five indoor races, the highlight being the World Championships, where he earned a silver medal in the 3,000 with 7:49.6. He also ran some cross-country, again winning the German title over the shorter distance of 3K. The track season started with some fine-tuning races over 800, 1,500 and 5,000, all this in preparation for an international 5,000 in Stockholm. In this race he was up against Ron Clarke, Jurgen May, and Ian Stewart, the English runner who would go on to a brilliant win in the Commonwealth Games later in the summer. It was Stewart who gave Norpoth the toughest time: the two were only 0.2 of a second apart at the end. Norpoth’s winning time in beating Stewart was 13:35.6. After the race, Stewart, a fierce competitor, admitted that Norpoth had given him a hard race and vowed he’d be back for more hard racing.

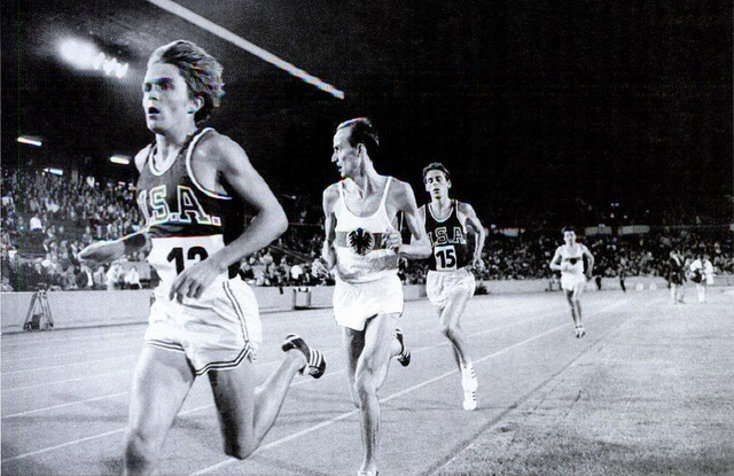

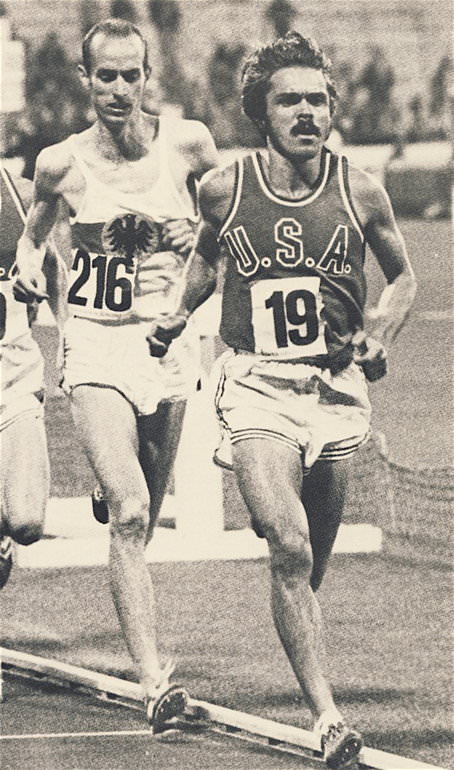

|

| Prefonaine tried unsuccessfully to run Norpoth off his feet. |

Norpoth’s second big race before the European Cup took place in a dual meet against the USA in Stuttgart. Here, Norpoth improved his seasonal best with a 13:34.6 victory over another very competitive runner, Steve Prefontaine. The 19-year-old American led from the start and stayed in front until Norpoth sprinted away in the last 250. According to Kenny Moore, “Pre was mad from the instant he crossed the finish line. On the victory stand, while receiving their medals, Pre got into Norpoth’s face. ‘I think it’s chickenshit,’ he hissed, ‘for an old guy like you to let a little kid do all the work and humiliate him in the end.’ The crowd saw how hot he was, and started to jeer. Norpoth replied eloquently without a word, lifting his gold medal to the crowd and then holding it right under Pre’s nose.” (Kenny Moore, “Leading Men” Going Long, p.177)

Victories continued to come Norpoth's way. After winning the German 5,000 title in 13:53.6, and beating a strong international field over 3,000 in Cologne (7:49.6), He was back in Stockholm for the European Cup final. The pace in the 5,000 was very slow, which suited him just fine. He was able to outsprint the field for a 14:25 clocking. His competitive year had ended on a high note.

1971

Now 28, Norpoth started his 1971 track season quietly with a few low-key races before the German Championships in early July. After winning the German 5,000 title yet again, he went straight into his third Euros in Helsinki. This time he came up against Juha Vaatainen of Finland, who had already won the 10,000 in front of his hometown fans. The Finn’s sensational kick worked again in the 5,000 when he made a break with 300 to go and left Jean Wadoux and Norpoth in his wake. Norpoth held on to second place into the last straight but was unable to fight off Wadoux. Vaatainen’s margin of victory wasn’t great (0.8), but it was decisive: 1. Vaatainen 13:32.8; 2. Jean Wadoux 13:33.6; 3. Norpoth 13:33.8.

This was Norpoth’s last 5,000 of the year, for he raced only over 1,500 and the Mile after the Euros. Following a win in London (3:43.9), he had one of his lowest ever placings with a fourth in a Mile race in Berlin, despite running a lifetime PB of 3:57.2. In this race he was beaten by Jipcho, Arese and Keino. He then went on to win a 1,500 against Russia and to lose another against Vassala of Finland. Finally, he went to Kenya in October and ran second to Keino twice.

1972

|

| Olympic 5,000 No one wanted to lead:One of the rare times when Norpoth led in the early stages of a race. |

Yet another Olympics beckoned. And this time it was in Norpoth’s home country. He started the season with a 3:44.2 victory in Germany before going to Helsinki for a 5,000. This race was a big morale booster for he won in 13:34.8, finishing ahead of three top-class runners: May, Viren and Vassala. Back in Germany he ran exactly the same time to win the 5,000 in a dual meet with the USSR. Then, after winning the national title in 14:11.8, he rested from competition for the six weeks before the Munich Olympics. The only run of note during that time was a 3,000 time-trial in 7:54.2 in front of a football crowd. His preparation for the Olympics was promising if not inspiring.

The heats for the 5,000 were tough: only the top two in each of the five heats were automatically through to the final. Norpoth’s heat was the fastest (13:31.8, a new Olympic record), and he could do no better than third. It was won by Puttemans, with Prefontaine, Norpoth’s old rival, in second (13:32.6). Fortunately, Norpoth’s time was the fastest of the “losers” (13:33.4), so he advanced to the final.

No one wanted to lead in the final. The first 3,000 (8:20.2) was 13.8 seconds slower than the pace in the 10,000 final. With four laps to go, Prefontaine put in laps of 62.5 and 61.2. This surge left Norpoth 8m behind the leading bunch of five and no longer in contention. Nevertheless, his last four laps were covered in 4:06, and he finished a respectable sixth in 13:32.6, which was 6.2 seconds slower than the winner Viren. Still, this result must have been a disappointment for him, especially as he was running in front of a predominantly German crowd.

1973

|

| Norpoth waits to outsprint StevePrefontaine in their final encounter. |

Norpoth now entered his twelfth and last international season. Nevertheless, there was more brilliant running to come; in fact, he was unbeaten until his very last race. After starting off with two comfortable wins over 3,000 and 1,500 (7:57.8 and 3:45.5), he won the 5,000 in a dual meet with the USSR, beating Sviridov in the brisk time of 13:36.4. Then following two more 3,000 victories on home turf (8:11.6 and 7:57.0), Norpoth prepared for another encounter with Prefontaine in a match against the USA. After Prefontaine’s petulant behaviour during their first encounter, and after being beaten twice by him in the Munich Olympics (heat and final), Norpoth had a lot of motivation to win this race. And what a performance the 30-year-old German put on! He not only won the race but also recorded a 5,000 PB. To be fair, Prefontaine was suffering from sciatica. The American tried to push the pace after passing 3,000 in 8:02, but he said that the sciatica prevented him from doing this: “I wanted to…step up the pace, but I couldn’t go any faster. My race in the 5,000 is in the last five laps, but when I’d start to move that last mile, my back would tighten up.” (Tom Jordan, Pre, p.64) Norpoth merely stayed close to the American, who was nevertheless running at close to his PB, and then kicked with 200 to go to open up a comfortable lead at the end: 13:20.6 to 13:23.8. His time improved his 1966 PB by 4.2 seconds and was a new German record. Despite his sciatica, Prefontaine was very close to the 13:22.4 PB he had run two weeks earlier.

|

| Norpoth's last race. He finishesthird behind Foster andKuschmann. |

Norpoth’s career was almost over. Apart from a 3,000 victory (7:55.6), he had just four more races, two in the German Championships and two in the European Cup. He was again German 5,000 champion, winning his heat in 14:09.6 and the final in 13:48.2. In the European Cup Semi-final, he won the 5,000 in 13:47.82, beating Paivarinta, Korica and Malinowski. The final was in Edinburgh. Here he was up against Kuschmann, Viren, Tijou, Zhelobovsky and Foster. It was not a great field, as Viren was not in top shape, and Kuschmann had not yet proven himself, Foster was more of a 1,500/3,000 specialist and Tijou and Zhelobovsky were not quite at Norpoth’s level.

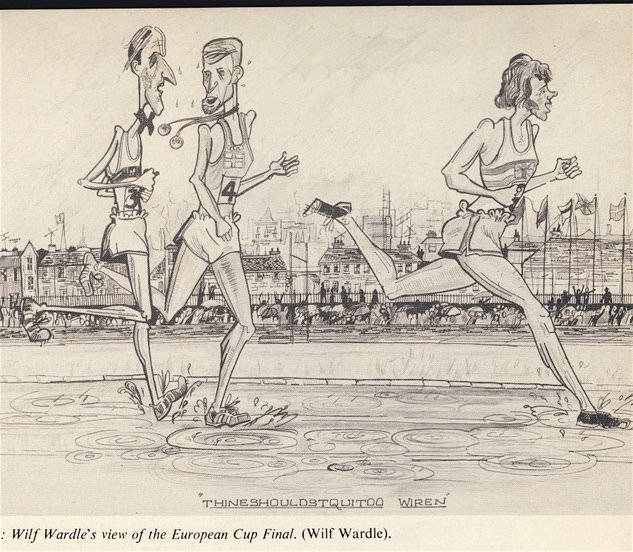

|

| Wilf Wardle's cartoon: Norpoth (left) tells Viren to retire, while the youngster, Foster,wins the 5,000 in the Euro Cup. |

The race began at such a funereal pace that there was booing after the first lap. After the first 200 was covered in 40 seconds, Viren upped the pace to 75 for the first lap. But the race continued very slowly. At 3,000, Brendan Foster injected a 60-second lap and only Kuschmann, Norpoth and Zhelobovsky went with him. Foster kept the pace fast until he was passed at the bell by Kuschmann and Norpoth, Zhelobovsky having dropped back. Norpoth held on to Kuschmann until he was passed by Foster on the back straight. As Kuschmann tried unsuccessfully to fight off Foster, Norpoth held on for third place (13:57.66) just three seconds behind the winner Foster. Norpoth was reported to be tired at this stage of the season, and clearly he hadn’t raced with his usual vigour in this race. It was time for him to retire.

Retrospect

Norpoth consistently raced as if he expected to win; he was always up with the leaders from the start. And he did win 78% of his races. With such a great competitive record, it is surprising that he never won a major title. He always ran well in the Euros and the Olympics but never managed a gold medal. Perhaps he lacked some of the inspiration that often leads to a gold medal. He certainly had a competitive flair and a strong kick. But despite this, there is no doubt that Harald Norpoth was one of the great runners of his era. He will be remembered for his consistency, determination and competitiveness.

Special thanks to Andreas Janssen for his statistical help. See his website The Great Distance Runners.

5 Comments