Glenn Cunningham Profile

1909-1988

|

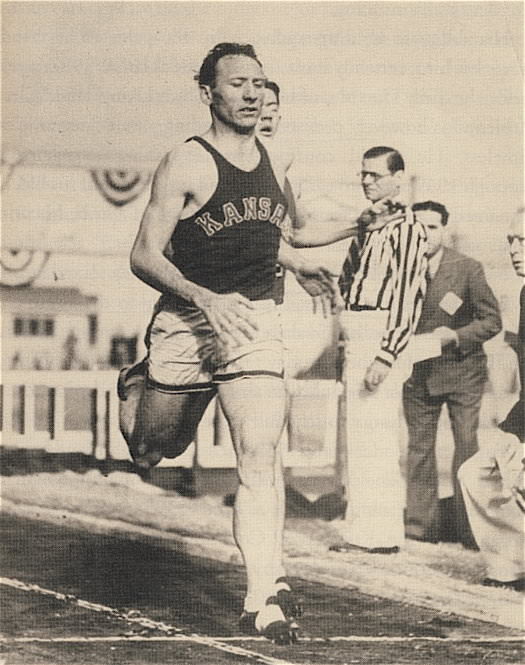

| Leading the 1,500 final in the 1936 Berlin Olympics. |

The life of 1930’s American miler Glen Cunningham has now become part of American folklore. It is the story of a young Kansas boy of pioneer farming stock who faced adversity with courage and determination to become a world-famous hero. This story, as it grew into folklore over many printed versions, has often been embellished with fictional details. However, the actual facts are powerful enough.

When just seven years old, Glenn Cunningham was badly injured by a woodstove explosion that killed his brother. He spent over a year recuperating upstairs in his parent’s home before he was able to venture outdoors. His legs were so badly burned that it took him more than six months to stand, yet alone move. Yet through determination and self-discipline he learned to walk and then to run, eventually becoming a world-class runner.

As a miler, he became one of the event’s most frequent winners with a career stretching from the late 1920s to 1940. He placed fourth and second in the 1932 and 1936 Olympic 1500’s and set many world records, most notably for 800 and the Mile outdoors and for the Mile and 1,500 indoors. His forte was indoors; over a stretch of almost ten years he was rarely beaten on the boards. At a time when indoor track was at its height of popularity in North America, he became a household name with six victories in the Wanamaker Mile, six in the Knights of Columbus Mile and five in the Baxter Mile.

It is difficult to assess how much his childhood injury affected his adult running career, but there is evidence that even in the 1936 Olympics, almost 20 years after the explosion, he was still handicapped by his injuries. Glenn Cunningham epitomizes the iron will of the American pioneer. His story has been an inspiration to countless people.

--------

The Accident

Born without a birth certificate into a family of itinerant farm workers, Glenn spent his early years in Kansas and Georgia. He was nearly seven when the family settled in Rolla, Kansas. It was here, some six months later that he was badly burned in a fire. On February 9th, he had arrived at school early with his elder brother Floyd to light the schoolhouse stove. Unknown to Floyd, kerosene can had been filled with gasoline, which is more flammable. Thus Floyd inadvertently poured gasoline on the embers in the stove and caused an explosion. Floyd was fatally burned, and Glenn, who was standing behind him, suffered serious burns to his legs. Glenn endured horrific pain for many months, especially when bandages were changed: “Each time a bandage was removed, it brought with it chunks of the boy’s leg muscles.” (Kiell, American Miler: The Life and Times of Glenn Cunningham, p. 41)

Because he avoided any infection in his wounds, Glenn’s life was never in danger, nor was amputation ever considered. (Many have written of him narrowly escaping death, of him facing amputation, of him spending six months in hospital. None of this is true.) But the attending doctor initially doubted that Glenn would ever be able to walk.

Recovery

After six weeks, he was “able to sit up a little,” according to the local paper (Kiell, p. 52.) After six months in bed, he tried unsuccessfully to stand: “My legs wouldn’t move,” he wrote later. (Don’t Quit, p. 53) But with self-massaging of his legs, which was done constantly, he was eventually able to stand. Next he learned to walk with the aid of a chair. Local people often visited to see him walk “lopsided…with crooked legs.” (Kiell, p. 53) After just over a year he was finally allowed outdoors, and his father, to give the boy goals, set him some simple chores. All the while Glenn massaged his legs compulsively and slowly strengthened his weaker left leg.

The next step was to run, something he had always enjoyed before the accident. According to his sister Myra, he would grab mules’ tails and “run behind them holding on to their tail because it would give him more support on his legs.” (Kiell, p. 54) As Paul J. Kiell points out, the foundation of Glenn’s recovery was “his love of and unwavering delight in physical activity.” (p. 59)

Progress

In the spring of 1919, just over two years after his accident, Glenn’s father became a victim of the ‘flu epidemic. Glenn and his younger brother Raymond had to run the farm. In a blizzard, when Raymond’s eyes froze shut, Glenn managed to get him home. Both boys almost died of exposure.

When just eleven, he returned to school, making the journey to and from school twice a day and covering four miles on foot. As soon as he could, he ran this distance. His teacher noticed how he was always exercising and massaging his legs. As well, he worked after school, sometimes with his father, sometimes driving cattle, and sometimes working at a local mill. Glenn recalls that one summer at the mill he worked “58 days straight, 16 to 22 hours a day.” (Kiell, p. 81) He began high school four years late at 18 and graduated three years later, after excelling at football, basketball and track.

First Races

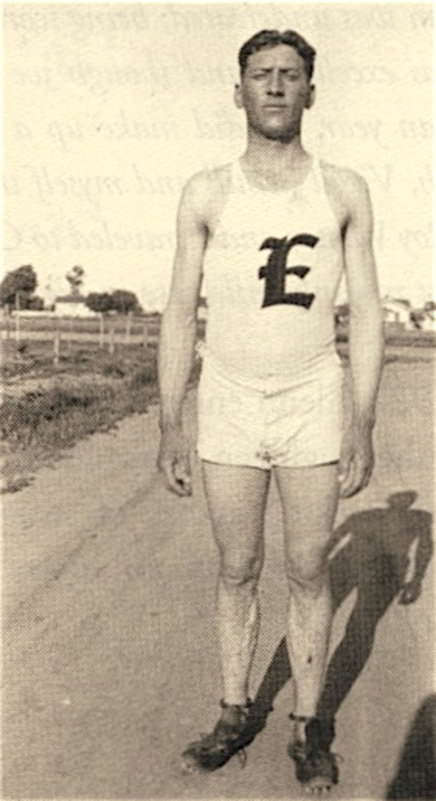

|

| High-school star. |

His sporting activities were a considerable problem because his father felt that Glenn’s energy would be better spent working. At first, Glenn competed in secret, but his success on the track eventually earned his father’s support. Glenn was still having troubles with his ankles when he started high school, but from the first time out he was the best runner in the school. His main problem was warming up his legs, which took much longer than usual. (Fifteen years later, Lovelock became angry at him for taking a long time to warm up for The Mile of the Century at Princeton.). Because he still lacked confidence in his legs, he would always start slowly in case they broke down. (Kiell, p. 105) He won every race in high school except one—a 1929 Interscholastics race in Chicago, when he had a fever of 102. His best high-school time was 4:24.7, achieved in winning his second Interscholastics race in 1930.

University of Kansas

Glenn had been saving for university, but his savings had evaporated by the time he enrolled at the University of Kansas. According to Kiell, he had loaned money to many of his friends who had been hit by the 1929 stock market crash. So he had to work his way through university, while both running and studying. Bill Hargiss, who became his coach, was immediately impressed by Cunningham, noting that the freshman had “a will and determination to succeed that is almost undeniable” and that “deep in his mind he feels that there is not a man living whom he can’t defeat in a footrace.” (Cunningham Trains: An Intimate Story, 1933)

Cunningham, while training lightly by modern standards, practiced advanced methods for the early 1930s. Hargiss used interval training with 220s, 440s and 660s. He rarely made Glenn run more than 3/4 mile continuously in practice. Apart from Saturday competition, Glenn did only two hard track sessions a week, filling out his days with a long walk, skipping, shadow-boxing and calisthenics and perhaps a light sprint session. Hargiss was also a believer in weight training, which at the time was frowned on by most track coaches. Glenn’s legs were still troubling him with “excessive pain” (Kiell, p. 137) in his freshman year, but then they improved. Hargiss has described the condition of Glenn’s legs at this time: “Both his legs were scarred to the bone, one with scars that reached to his hip and one traverse arch in his foot that was broken.” (Kiell, p. 136) Continual massaging continued, with the aim of preventing the formation of fibrous tissue.

When Glenn started competing as a sophomore he won all his cross-country races but one in his first season. Then he began to win indoors. In his first big indoor race in Chicago, he was still stripping off his sweats when the race started, but he caught up and won in 4:19.2. All of a sudden he was considered an Olympic possible.

Los Angeles Olympics

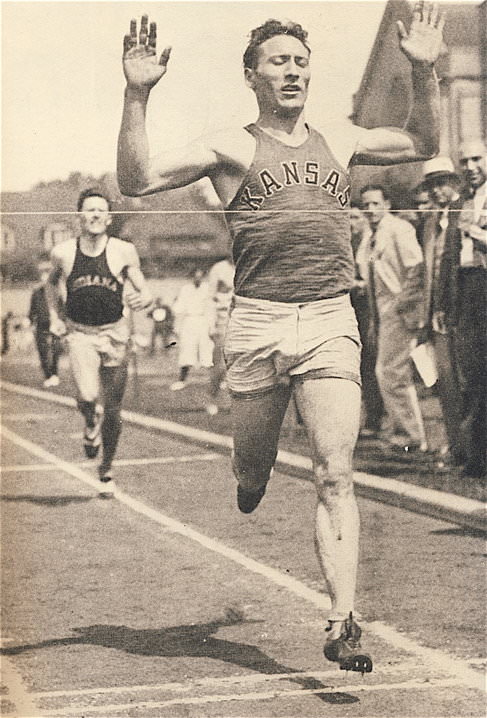

|

| Qualifying for the 1932 Olympics. |

Improvement came quickly in 1932. He won the Intercollegiate title in a record 4:11.1, which was the fastest Mile ever run in the USA and six seconds under the collegiate record. Although his coach had wanted him to make his effort from 300, Glenn had other ideas: “I though it would be my best bet to wait till the last turn, because I did have a lot of trouble with my legs. A lot of times, sprinting would just about kill me. It felt like somebody had hit me with a dagger in my legs, especially in the thigh where the deepest burns had been and where most of the chunks of muscle had fallen out.” (Kiell, p. 152)

Now qualified for the Olympic trials, Cunningham did not work that summer. For the first time in his life he “just trained.” (Kiell, p.152) In the Olympic trials in Palo Alto, Cunningham finished a safe third to qualify. To do this he beat the new American record-holder Gene Venzke.

The 1932 Olympic 1,500 final in Los Angeles was watched by 120,000. Glenn ran an atypical race, taking the lead just after 400 (60.5) had been covered. A lap later Edwards of Canada upped the slow pace and only Glenn went with him. The pair quickly opened up a ten-yard gap on the bunched field. The duo still had a 20m lead at the bell (3:07). Cunningham, after taking the lead again, was passed by Edwards on the back straight. The chasing group closed on Cunningham, and Beccali took him at the crown of the bend and went on to pass Edwards for victory. Cunningham held on to fourth (3:53.4) after being passed by Briton Jerry Cornes. It was a very creditable performance for his first major international race, especially since he was suffering from ‘flu: “I woke up [on the day of the final] with a throat so sore that I could hardly croak.” (Never Quit, p. 118)

College Boy at the Top

Cunningham returned to the University of Kansas in the fall as the fastest miler in the world for 1932 and as a fourth-place Olympian. And he was about to take the popular American indoor track season by storm. The American press milked the stories of Glenn’s leg burns for all they were worth and built up a rivalry between him and Gene Venzke, who had the indoor Mile record (4:10). Madison Square Gardens was at capacity with 17,000 for their first confrontation in the Wanamaker Mile. Venzke had been unbeaten in the 1932 indoor season, but 1933 was a different story. Cunningham had no trouble hanging on to Venzke until the last lap, when he opened up a two-yard gap and then increased it to eight yards round the last bend to win in 4:13.

In the 1933 indoor season, Cunningham went on to defeat Venzke four out of five times and became the hero of the New York media. But he also had running obligations to Kansas University. He ran a fast outdoor time for the Mile when winning the NCAA title by 45 yards; his time of 4:09.8 was a new American record. Then he was picked for an eight-man American team to tour Europe. He left on July 19, just four days after Lovelock had set a Mile WR at Princeton with 4:07.6. In Europe he continued his winning ways with an unbeaten run of 20 victories. His opponents included Ny of Sweden and Szabo of Hungary, but not Lovelock and Beccali. His best performances were 2:23.9 for 1,000 metres (0.3 outside the WR) and 3:51.6 for the fourth fastest-ever 1,500 time.

World Records—Indoors and Outdoors

After so many good times in 1933, the 1934 indoor season was awaited eagerly. Of course, Cunningham and Venzke would continue their rivalry, but there was a new runner on the scene to challenge them in Bill Bonthron. This talented 20-year-old had pushed Lovelock to his 4:07.6 the previous summer, running 4:08.7 himself. Bonthron appeared late in the 1934 indoor season to beat Cunningham in the Baxter Mile. Otherwise, Cunningham ruled supreme. He again defeated Venzke in the Wanamaker Mile with 4:11.2. But his best time of the season came in the Knights of Columbus Mile, where he set a new Indoor WR of 4:08.4. Only Lovelock had run faster, indoors or outdoors.

While preparing to graduate from Kansas University, Cunningham now faced the outdoor season. It started with a two-man race in the Penn Relays against Venzke. Glenn’s fierce finish gave him a 15-yard margin at the tape with 4:11.8. After graduation, Cunningham went to Princeton for another Mile race against Venzke, but this time Bonthron was also on the start line. This was a race between the top three American milers, who apart from Beccali and Lovelock, were the best over 1,500/Mile in the world.

|

| Setting his 4:06.8 Mile world record. |

Before 25,000 spectators, who were rooting for the hometown boy Bonthron, the trio started with a 61.7 lap, Venzke leading. On the back straight Cunningham eased into the lead and led after two laps (2:05.8), with Bonthron and Venzke on his heels. Then the race became interesting as Cunningham applied the pressure, opening a 10-yard gap around the bend and then extending his lead to 20 yards on the back straight. His time at the bell (3:07.6) indicated an unusually fast time for the third lap of a Mile—61.8. The crowd was now focusing on Cunningham and the possibility he could eclipse Lovelock’s 4:07.6 WR with a sub-60 last lap. If ever there was a time for strength, this was it. And no one was stronger than the Kansas “Iron Man.” He maintained his pace to the tape, claiming a new WR of 4:06.8.

And he had done it on his own, as Bonthron (4:12.5) and Venzke (4:16.0) lagged far behind. He had led for 2.5 of the four laps. Arthur Daley of the New York Times was really impressed: “No man had ever turned in so fast a second half in a record race [2:01.0], and no one could possibly stay with the running marvel who did. That was the entire story.” (June 17, 1934) There is another aspect that adds to the Iron Man image: Glenn had run this race with a bad ankle that had been taped. Coach Hargiss later wrote that after the race the ankle became so swollen that the tape had broken and that Glenn was unable to walk the next day. (Kiell, p.194)

He still ran two races the next week. Not surprisingly, in both races, the somewhat lame Cunningham was beaten by Bonthron, who ran 4:08.9 for a Mile in the NCAA meet in Los Angeles and then a WR 1,500 (3:48.8) in the AAU meet in Milwaukee. Cunningham’s times were 4:10.6 and 3:48.9, the latter a really fine time that also beat the WR. In both races the gallant Cunningham made all the running, only to be defeated by Bonthron’s devastating kick. It is hard to gauge how much he was affected by his injured ankle in these two races, but it must surely have slowed him a little for he was unable to “run away” from Bonthron as he had done at Princeton.

Career Choices

|

| Regular massage on his damaged legs |

Following this amazing season, Glenn got married in July and then took his wife with him on a US track team tour of Japan in September. It had been a momentous 1934 with two world records, graduation and marriage. On top of that, Glenn was a national favorite for the popular indoor meets. Although there were strict amateur rules, it is hard to imagine how he was able to survive financially as a student without some income from his running. And he has admitted that he would charge for first-class tickets and accommodation, use the cheapest available, and pocket the difference. But with the huge indoor crowds he was drawing, there must have been some other financial incentives offered him.

It was expected that he would retire at this point. After all, just about every top American athlete did retire once university was over. But Glenn bucked the tradition, despite his new marital responsibilities. He continued running at the top level and at the same time enrolled in graduate school at Iowa University. (In 1936 he would earn a master’s degree in Physical Education.)

Another Successful Indoor Year: 1935

Despite recurring problems with his ankle, Glenn would continue to win races. His first big race was the Wanamaker Mile where he faced Bonthron, Ny of Sweden, and of course Venzke. The early lead changed several times, Cunningham, Bonthron and Venzke all taking turns. Lap times were 64.8, 62.6 and a fast 61.9 when Cunningham piled on the pace. Bonthron, who was in second, was passed by Venzke after nine laps. Then Venzke took Cunningham at the bell. But the Kansan fought back to claim a one-second lead at the tape in 4:11.0.

The wins continued: he took the Baxter Mile in 4:09.8, again beating Bonthron and Venzke; the AAU 1,500 in a new indoor world record of 3:50.5; the Nights of Columbus in 4:14.4; and a 1000 Yards event in a world-best time of 2:10.1. The world-record AAU win was particularly impressive as he ran a cruel 2:01.9 for the first 800 to break Bonthron and win by 30 yards.

Difficulties Outdoors

The 1935 outdoor season was not so successful, partly because of a bout of flu from which he didn’t fully recover “until well into the summer.” (Kiell, p. 209) This could well explain his poor showing against Lovelock in the May Princeton Invitational. The New Zealander described the race in his diary, especially noting how Cunningham held up the start of the race: “Five of us were stripped and standing ready, as requested by the starter, for some minutes while Glenn Cunningham still jogged around in his warms. I was pretty nervous so that annoyed me. When he came near us, I very quietly asked him to hurry along as he was keeping the rest of us waiting.” (Colquhoun, As if Running on Air: The Journals of Jack Lovelock, p. 174) This incident shows that Lovelock didn’t understand Cunningham’s difficulty warming up his scarred legs, but it also shows how determined Cunningham was to be properly warmed up—even if it meant keeping his fellow competitors waiting.

|

| Trying to drop Lovelock and Bonthron. Princeton 1935. |

Using the same tactics that had won him the AAU title, Glenn took the lead after a slow first lap to run what was called “fastest second lap in the history of first-class miling.” (Colquhoun, p. 176) This was 60.8. Still trying to drop Lovelock, he barely slowed on lap 3 with a 63.2 to pass the bell in 3:09. Lovelock was still right there, his light step barely audible to Cunningham. On the back straight Cunningham slowed almost inviting Lovelock to pass him, but the New Zealander, noting that there was no one close behind, waited until the end of the final bend to make his effort. He felt only “momentary resistance” from Cunningham and swept away to a clear 4:11.2 victory, while Bonthron also passed Cunningham for second: 4:12.6 to 4:13.0.

Cunningham ran one more important race in the 1935 summer, winning the AAU 1,500 from Venzke in the world’s fastest time of the year (3:52.1). By this time was getting busy with commitments outside running. As well, he was appointed by the White House to sit as a member of the new National Youth Administration. In fact, he had already been involved in helping youth and it later became his lifetime mission.

Olympic Build-up

Nevertheless, Glenn planned to run the big indoor meets in 1936 and was definitely thinking ahead to the Berlin Olympics in the summer. But he wasn’t quite in the top condition of previous years when the indoor season began. He was third in the Wanamaker Mile, beaten by Joe Mangan and Venzke in a tight finish (4:11.0 to 4:11.1). Cunningham didn’t win the Baxter Mile either, as Venzke again beat him again. This time Glenn was a little faster with 4:10.2. Next came the AAU 1,500, where Cunningham set a ferocious pace. However, Venzke was strong enough to stay with him all the way and breeze past in the last 30 yards. The result was a new 3:49.9 indoor WR for Venzke, while Glenn beat his old WR mark with 3:50.5. After losing two more races in which he did most of the pacemaking, he refused to go to the front in the Knights of Columbus Mile. The result was a ridiculously slow race: 1:07, 2:34, 3:51 and 4:47. But Glenn won this one with a surprise burst near the end.

Still, he hadn’t quite found his top form yet. Outdoors, Venzke beat him in the Princeton Invitational 4:13.4 to 4:13.6. But the race was very close and the time good for the conditions. Then just prior to the Olympic trials, Cunningham for the first time raced the new NCAA champion San Romani. It was again a close race with Cunningham winning 3:53.2 to 3:53.6. In the trials, Bonthron took up the running after two laps, but the order at the bell was San Romani, Fenske, Venzke, Cunningham, and Bonthron. Cunningham moved up to second on the back curve and then waited until the homestretch to make his final move. San Romani put up great resistance but Cunningham just inched ahead at the tape, with both runners clocking a fine 3:49.9. Now into his best form, he was on his way to Berlin for his second Olympics--to meet Lovelock again.

1936 Olympic 1,500

Cunningham faced an impressive field for his second Olympic 1,500 final. All the medal winners from the 1932 final were there again: Beccali (gold), Cornes (silver) and Edwards (bronze). As well, fifth-place finisher Lovelock lined up beside Cunningham, who of course had finished fourth. The race was almost a replay of the 1932 race. And added to the mix were two talented American runners, Venzke and San Romani.

Before 112,000 spectators, Cornes set the pace with a 61.5 first lap. At 500 Cunningham, anxious to keep the pace high, took over. Lovelock moved up to second very quickly, showing he respected Cunningham’s strength. They passed 800 in 2:05.2. There was a lot of jostling in the third lap, but Cunningham, in the lead, was safe from any body contact. Just before the bell, Ny of Sweden took the lead, and Lovelock moved out on to Cunningham’s shoulder. Then Lovelock moved past Cunningham and Nyon the bend. Cunningham didn’t follow him past Ny—clearly a mistake because after passing the 12,00 mark (3:05.4 for a very fast 60.2 third lap), Lovelock took off at top speed.

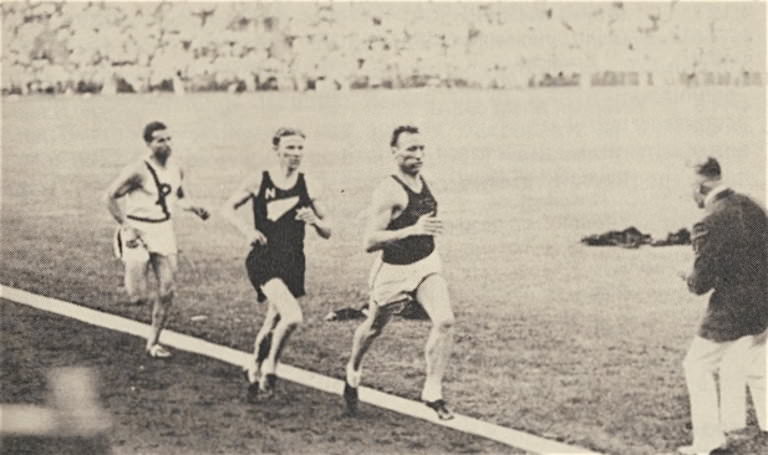

|

|

| Top: Lovelock passes Ny with 300 to go.Cunningham in third is stiitucked in behind Ny. Below: Cunningham in second has passed Ny,but Lovelock has escaped. |

Cunningham wasn’t able to react before Lovelock had a clear lead of four meters. Although now at full speed, he made no impression on the Kiwi’s lead down the back straight and now had to worry about Beccali, who had closed up behind him. The order of the first three didn’t change in the last 200 and Cunningham finished second, 0.6 behind Lovelock and 0.8 ahead of Beccali. He had run brilliantly, but one tactical error cost him the race: at 300 he should have been on Lovelock’s shoulder, not tucked in behind Ny. But it had taken a world record to beat him; Lovelock’s 3:47.8 was one second faster than Bonthron’s 1934 WR. Cunningham’s 3:48.4 was an American record, also inside Bonthron’s mark.

Since this was arguably Glenn’s most important race, it is necessary to return again to the condition of his legs. In his autobiography Never Quit he writes that on arriving at Berlin, “My legs became stiff as soon as I arrived,” as the weather was damp and cold. He attributed this stiffness to his burn injuries. (p. 101) Then he says that in the final, his legs did restrict him: “At the halfway point…I was about to pass [the leader] when my right leg suddenly buckled! I nearly fell. I recovered at once. But now new pains stabbed thorough my legs.” Then in the stretch before the bell, “But I was in trouble. Big trouble. My legs could give out at any moment…My legs were on fire. The realization enraged me. It seemed so unfair.”

Cunningham claims that he never talked after the race about these pains: “I made no mention of the leg pains.” (pp. 122-3) Not so. He did in fact mention them to Lewis Burton of the New York Journal-American: “I spoke to Cunningham after the race. He couldn’t hold back tears. He flicked the back of his hand impatiently on his fire-scarred thighs. ‘These legs, they weren’t right,’ he complained—as if they had betrayed him. ‘They’re no good.’” (George Smith, All Out for the Mile, p. 60) Never one to make excuses, Cunningham was clearly upset that his legs had let him down. How much they affected him in that Olympic final will never be known.

World Record for 800

Cunningham’s good form continued after the games. In an 800 in Stockholm, running against the 800 Olympic champion Mario Lanzi, he set a new world record in the 800 with 1:49.7. After running a 53.4 first lap, he knocked 1/10 of a second off the old mark and showed surprising speed for a 1,500 specialist. But in an October Mile in Princeton, he was past his peak and finished third behind San Romani and Lovelock in 4:13.

1937

Retirement was still far away, even though he now enrolled in a Ph.D. program. Cunningham, now 27, continued competing and was even looking ahead to the 1940 Olympics. And there was no easing up after his Olympic outdoor season. In fact his 1937 indoor season was one of his most successful as he won all the big indoor miles. In the Knights of Columbus Mile he was only 3/10 slower than his own indoor WR in beating Beccali, Venzke and San Romani. The media were all over him with praise.

Glenn was not quite so successful outdoors. He finally lost a race at the Princeton Invitational, where in a thrilling finish three runners ran side-by-side down the final straight. He finished third behind San Romani and Lash, with the first two clocking 4:07.2 and Glenn 4:07.4. All three were very close to Cunningham’s 4:06.7 WR, and the race showed that anyone who wanted to beat him had to run a very fast time. Cunningham went on to win another AAU title, but only after San Romani fell during a last-lap duel. In August he learned that his Mile WR had been beaten by Sydney Wooderson with a 4:06.4 clocking.

Astonishing Indoor 1,500 and Mile Times

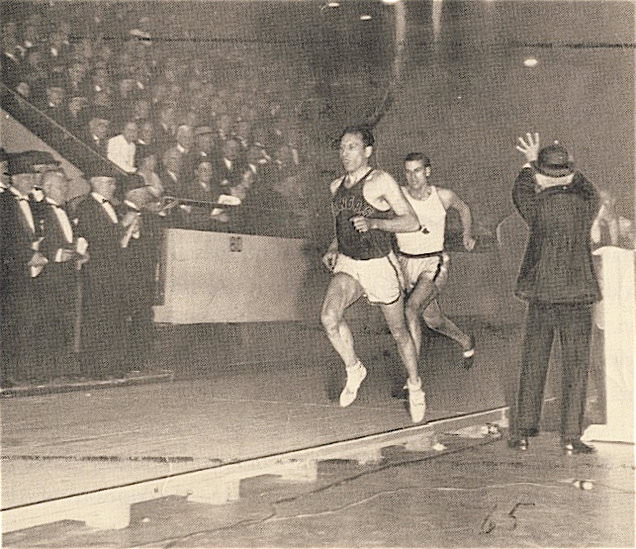

|

| Cunningham leads in a typical indoor race in the 1930s. |

The Ph.D. student was back again for the 1938 indoor season. Again he won all the major indoor races. He ran an stunning 3:48.4 to win the AAU indoor title, a time only ever beaten outdoors by Lovelock in the Berlin Olympics. It was the third time he had broken the indoor 1,500 record. Though he always professed that he ran to win, not to break records, Glenn did make one blatant attempt on the indoor Mile record. For this record attempt he chose the large Dartmouth College track that required only 6.33 laps for a mile, rather than the standard eleven. This meant 13 bends rather than 22, but still more than the eight on a standard outdoor track.

The March 3 race was set up by the Dartmouth coach, Harry Hillman, who used his university runners to pace Cunningham in what was billed as a handicap race. However, despite “considerable correspondence” with the AAU and “clear conditions of what must prevail” (New York Times, March 5, 1938), Hillman orchestrated what was a travesty of a race, with some runners jogging easily to meet up with Cunningham when he lapped them and even to cheer him on. As well, the top Dartmouth runner, Witman, dropped out at 880 after pacing Cunningham off a 5yd handicap. And another runner was given a huge 600-yard handicap so that he would be fresh enough to help Glenn in the latter stages.

It’s unclear how much Hillman’s choreography helped Cunningham, but he ran brilliantly with splits of 58.5, 2:02.5; and 3:04.2 to finish in the astonishing time of 4:04.2. The AAU did not accept the time as an American record because of the larger track, and the IAAF did not ratify it as a world record because it was paced. Nevertheless, as Bob Phillips has written, Cunningham’s 4:04.4 “remains one of the greatest achievements in track and field history” and in 1938 it made a sub-4 Mile “a very real prospect.” (3:59.4, p. 111) In the final analysis, Cunningham’s 4:04.4 was, at that time, the fastest Mile ever run by man.

Soon after he ran a bona fide indoor WR when he won the Knights of Columbus Mile in 4:07.4. Outdoors he won a thrilling Mile in the Princeton Invitational, after San Romani fell just before the tape when the two were running neck and neck. Glenn went on to win another national title at the AAU winning by inches from Fenske in 3:52.5. During this summer, Cunningham finished his doctorate in Biology, Health and Physical Education.

1939

|

| Still winning in 1939 |

While Europe was moving closer to war, Glenn won an outdoor Mile on January 1st in 4:13.1. He was now lecturing three days a week and fitting in some training and racing when he could. There were persistent rumours about retirement. He was 29 now and very busy with work. But he continued to win. He ran his seventh Wanamaker Mile and won for the sixth time. That indoor season he won all his races but two, a 1,000 race in Newark and a Mile in Chicago. Again he was the AAU indoor 1,500 champion with 3:54.6.

By the end of the season, he was exhausted from a combination of racing, work and travel. So when the new WR holder Wooderson was invited to the annual outdoor Princeton Mile, he was reluctant to enter. “I’m in no shape,” he told The New York Times. “I’ll compete only at the insistence of the Princeton officials.” (Kiell, p. 290)

They did insist, so Glenn lined up at Princeton with all the top American milers and Wooderson. The Briton led most of the race, but at a slow pace: 64, 2:08, 3:14. Not surprisingly there was jostling on the last lap; Wooderson stumbled after a clash, and Cunningham stepped on the curb and stumbled too. Wooderson seemed to be in shock and was out of the hunt. Meanwhile, Cunningham managed to get back into the race and he did well to finish second to Fenske (4:11.0) with 4:11.6. Wooderson was back in fifth. Glenn’s fatigue clearly affected him in the AAU 1,500 where he was only fourth. Perhaps the best indication of his health at the end of the summer was his weight: it had dropped from his regular 168lbs to 154.

End of Career

In January, Glenn announced that 1940 would be his last year of competition. Despite the likelihood of a cancelled Olympics, he was back for the 1940 indoor season, winning an early 880 race and then moving on to Boston for the first major Mile. He had been unbeaten in Boston for seven years with nine victories, but this time he just failed to catch Venzke (4:13.1). He was second again in the Wanamaker Mile after almost closing Fenske’s 25-yard lead. Still it was a good time; he ran 4:07.7 to Fenske’s 4:07.4. Though still as resolute as ever, Cunningham no longer had his habitual winning edge. He was always in the hunt, but he was no longer winning. And there were a lot of young runners after his scalp: the Rideout twins, Chuck Fenske, Louis Zamperini, Archie San Romani and Walter Mehl. For the outdoor season, he wanted to finish on a high note, so he paced himself through the summer, aiming to run a farewell race in the Fresno outdoor AAU. And what a farewell it was. Glenn took the lead from the start and set a blistering pace and held the lead almost to the tape. But a young Walter Mehl spoiled the fairytale finish to the Cunningham career as he passed the veteran at the tape to win 3:47.9 to 3:48.0. Oh so close to Lovelock’s 3:47.8 WR!

After he retired, Cunningham discovered that he had been living for years with abscessed teeth that were leaking poison into his system. He believed that the pain in his legs that he had suffered from in his later career had been caused by the poison from these abscessed teeth. The teeth had originally been loosened some ten years earlier when he was hit in the mouth with a baseball. This adds yet another dimension to the leg problems that he had dealt with throughout his running career. And it is yet another indication of the inner strength of this remarkable man.

With his Ph.D. qualification, Cunningham was appointed Director of Health, Physical Education and Athletics at Cornell College in Iowa. He was there until he joined the US Navy in 1944. Following demob in 1946, he returned to Kansas, divorced and remarried. Then, after working in various jobs and giving inspirational talks, he bought an 840-acre ranch in 1950. Thereafter he devoted his time to helping troubled children—and to fathering twelve children of his own. He supported his vocation with lecture tours but never really had enough finances for his ranch. He used outdoor farm work and animal husbandry as therapy for the thousands of children who passed through his care. His ranch became full of animals which he obtained through trade with local zoos. He kept his farm running until 1973. After selling, he continued to work with children, though on a more modest level. In 1988 he died after suffering a heart attack while driving his truck.

Retrospect

Cunningham running career poses two intriguing questions. Question 1: How much were his performances affected by his damaged legs? This profile has provided several comments that Cunningham made on the problems with his legs in races. His race tactics, especially in his early career, were often adapted because he feared his legs might give out. This fear often prevented him from front-running, his most favored mode of racing. Further, he mentions stumbling in races. It’s not known how often this happened, but it did happen in the 1936 Olympic final. Of course, back in the 1930’s there was no way to measure his running efficiency; bio-mechanical research with treadmills came later. But overall, anecdotal evidence strongly suggests that he was handicapped by the damage to his legs.

Question 2: Where did his famous iron will come from? There is another American distance runner who was famed for his iron will: Max Truex. Significantly, both Cunningham and Truex, in early life, were involved in serious accidents in which they lost a brother. Don Truex, a brother of Max, has suggested that the car accident that took the life of brother Gene was the source of Max Truex’s iron will: “It was that event—he was trying to prove something. I never quite understood it.” (See Max Truex Profile on this site.) So possibly the trauma Glenn experienced in losing his brother Floyd triggered something deep in his psyche that enabled him to endure great pain and to push himself to the extreme. Of course, his tough upbringing under a demanding father shaped his character too. Thus, while all successful runners have unusual determination, Glenn stood out as an exceptional case of iron will.

Conclusion

There is always a story behind a great runner’s stats, but rarely such a rich story as Glenn Cunningham’s. Of course, it’s important that he broke the Indoor Mile WR three times (1933: 4:09.8; 1934: 4:08.4; 1938: 4:07.4), that he broke the indoor 1,500 WR three times (1934: 3:52.2; 1935: 3:50.5;1938: 3:48.4.), and that he broke the outdoor Mile and 800 WRs (4:06.8 and 1:49.7). But surely what’s more important is how he achieved these records. As well, he was a racer, with more major victories than anyone of his era. Anyone who raced Glenn Cunningham knew that he was in for one hell of a race—every time. And then there are the fourth and second places in his two Olympic 1,500s. The badly burned Kansan farm boy certainly made an impact on the running scene.

Note: In writing this profile, I benefited greatly from reading Paul J. Kiell’s excellent American Miler: the Life and Times of Glenn Cunningham. I recommend this book to anyone interested in a more detailed account of Cunningham’s life.

3 Comments