Bob Schul: Profile

b. 1938

American Bob Schul is best known for his stylish and confident win in the 1964 Olympic 5,000 in Tokyo. He also ran one WR (Two Miles), set five American records and won three American titles. His achievements are all the more remarkable because he suffered throughout his career from severe allergies and ensuing asthma. Schul’s success as a runner is testimony to his determination and competitive spirit.

Early Days

|

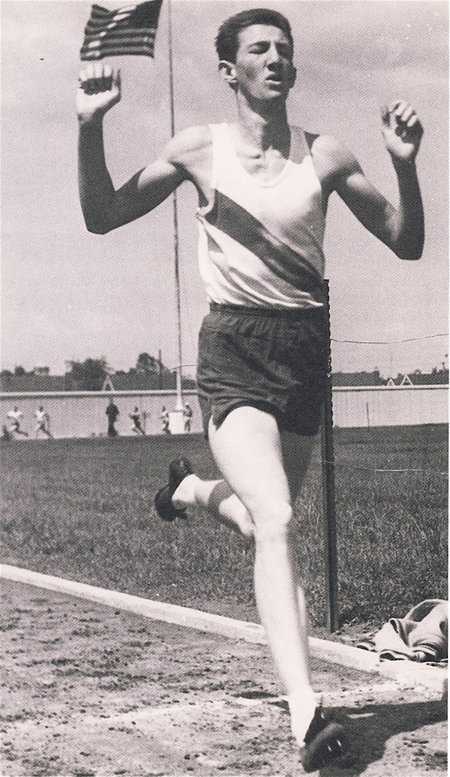

| High-school victory. |

Many great distance runners have a history of hard physical work in childhood, and Schul is no exception. The second of four brothers, he grew up on an Ohio farm, where he was inevitably given chores involving physical work. “When you live on a farm,” he says, ‘there is work to be done, and you do it as there are no excuses…. The consistent, hard work of a farmer is similar to the consistent effort necessary to be a great athlete.” (Bob Schul Interview: garycohenrunning .com) One of his jobs was bringing in the cows from the pasture: “So after school I began a long trek across the road and down to the pasture…. During hot days, the cows would go deeper into the woods where it was cooler…. To get the job done more quickly, I began running to find them.” (Schul, In the Long Run, p.16) But his childhood was far from perfect because he suffered badly from allergies, almost dying from an attack at 15 months. Nevertheless, Schul participated in team sports and made his high-school basketball and football teams. And he showed good endurance in cross-country and the Mile. He ran 5:10 in his freshman year, 4:50 the next year, and 4:34 for his last two years in high school.

After a year of working and no running, Schul joined the University of Miami (in Ohio) track team in 1956. Out of shape and constantly dealing with allergies, he made a slow start and was initially put on the 220 and 440 relay teams. It was at this time that Schul learned to sprint—an ability that put him in good stead later on. He also learned how to deal with his asthma attacks in a way that also helped his running: “I learned to breathe deeply and slowly which later on would be a plus as the deeper you breathe the more oxygen that gets into your lungs and then to your muscles.” (garycohenrunning .com) Further, he developed a positive attitude to his allergies: “If I had asthma problems in training I just looked at it as something tougher I had to overcome, which may have been similar to training at altitude since I couldn’t process as much oxygen.” (garycohenrunning .com)

In his sophomore year, Schul started to show promise and was challenging his team’s top runner, Dick Clevenger, in cross-country races. He ran 3rd in the Mid-American and 20th in the NCAA Championships. He also showed speed, running a sub-50 440 in an indoor relay. This combination of speed and endurance bode well for the outdoor track season. And his breakthrough came in the Mile with a 4:14.4 and then a 4:12.1.

Air Force Runner

Following a family tragedy, Schul quit university after two years and joined the Air Force. He got back into running after seeing a notice about the Air Force track championships. After his basic USAF training, he was very lucky to be transferred to Oxnard Air Force base in California, where selected Air Force athletes were training for the 1960 Olympics. At a training session he met Max Truex, a 1956 Olympian. Truex took Airman Schul under his wings and gave him training schedules (“Harder than I had done in college”).

In the spring of 1960 Schul ran his first two steeplechases (10:45 and 10:15). He then ran in the US championships, clocking 3:55 for fifth in the 1,500 heats. This was his best time of the year, close to the 4:12 Mile he had run at university. Following this, Schul went back to hard training. Luckily his hours of duty enabled him to train with the Olympic qualifiers at Oxnard. And in such company he began to improve to the point where he could stay with Truex on some of their runs.

Introduction to Igloi

Schul’s improvement motivated Truex to introduce Schul to the great Hungarian coach Mihaly Igloi, now resident in California. On a visit to San Jose, he did some training under Igloi: “…it was more work that I had ever dreamed possible,” he wrote in his book In the Long Run, where he gives a wonderful description of his initial sessions with Igloi athlete Lazslo Tabori. After these workouts, an impressed Igloi offered to coach Schul and said Schul could do the same workouts that he was giving Truex to do at Oxnard.

In 1961, with Igloi’s schedules, Schul’s steeplechase times came down fast. After an initial 10:03, he dropped almost a minute to 9:10 to qualify for the AAU. There, in front of Igloi, he ran brilliantly, finishing third in 8:53.6 behind Deacon Jones and George Young. This earned him a place on the US team against West Germany. Running with Jones as his partner, Schul was leading after 300, and he held this lead until the last 70m, when Jones just got by him. He improved again with 8:47.8, just 0.2 behind Jones. He had arrived on the international scene.

Returning to Oxnard in September, Schul received some great news: Igloi had moved to Los Angeles and was coaching at USC. This meant that, with some extra driving, Schul could work out fairly regularly with the Hungarian coach. That winter he trained diligently twice a day, rising at 5:15 am to get in his morning session before his military duties. And three times a week he drove to LA to do his second session with Igloi. When the indoor season started, a couple of Two-Mile races in the 8:50s showed that this grueling schedule was working.

He kept up his twice-a-day routine until the outdoor season began in April: “It was a Spartan existence. I did little else but work, eat, sleep and train. There was no time to date or to have any kind of social life, because I was always too tired. My commanders were always asking why I was so thin and didn’t seem to have much energy.” (Schul, p. 67)

|

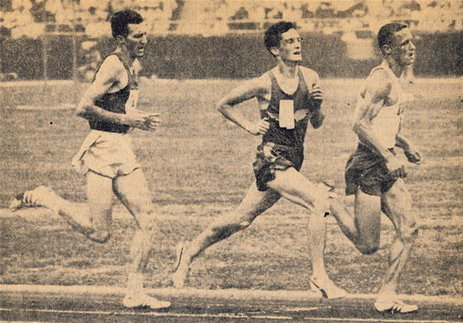

| Leading the field. Beatty (7) trails. |

But then things went wrong. In his first outdoor race, he felt that body “had just been drained of all its energy.” (Schul, p. 68) Then in a big Two Miles, he finished almost half a minute behind Jim Beatty, running just under 9:00. After another two very slow races, Schul was diagnosed with mono. This meant that he would be unable to tour Europe; his 1962 track season was over.

Schul didn’t give up. By mid-September, he was well enough to resume normal training, and he settled down to a second winter of two-workouts-a-day under Igloi. The only difference was that he decided to cut down on the three trips a week to LA. The training progressed well, and there was a brief respite for the indoor season. He first ran an 800 relay leg in 1:53 and then won a Two Miles in 8:51.6. In the AAU he ran a fast Two Miles (8:37.5) behind Jim Beatty, who ran a WR with 8:30.7. Despite a niggling injury he ran in the outdoor Pan-Am Games, winning a bronze medal in the 5,000. But the injury prevented him from proper training on his return: “I began to lose the endurance I had built up over the winter.” (Schul, p. 81) He was unable to run the AAU, but he did recover to run 8:44.6 and 8:46..6 for Two Miles in August. Still, he had put in two very hard winters and had broken down each time in the spring when the competition started.

Return to Ohio

Now out of the Air Force, Schul had to decide what to do. His decision was affected by his marriage to Sharon. Should he stay in California to train with Igloi, or should he return home to Ohio and finish his education? Another factor was the break-up of his training group: Truex and Tabori were retiring, Beatty was moving back to North Carolina, and Grelle was thinking of moving back to Oregon.

On September 1, 1963, after a painful talk with Igloi, Schul drove with his wife back to Ohio and enrolled in university, where he was still eligible to compete. With the Tokyo Olympics in mind, he decided to coach himself using Igloi’s principles. But it was far more difficult training in an Ohio winter; as well, there were no good facilities. He eventually found a grass area of three grass hockey pitches where he could run 330 straight. But when the snow came he had to run on an old unbanked indoor track and under a football stand. “It was the toughest training mentally that I ever did,” he recalled. (garycohenrunning .com) Looking back today, he says, “I don’t know how I did it.”

To get a break, he decided to compete regularly indoors. A Three Miles victory in 13:31.4 (second-fastest indoor time ever) was a good morale booster. He followed this up with a 13:36.9 in Toronto behind Albie Thomas, who set a WR of 13:26.4. After another 13:32.4 behind Bruce Kidd and a Mile victory in 4:08.9, he beat Ron Clarke in a Two Miles with 8:42.2. After two more races over Two Miles (8:42.8 and 8:47.3), his busy racing schedule took its toll, and he developed anemia. Still, Schul continued competing and managed two more victories over Two Miles. It had been a wonderful indoor season, but was it the right way to prepare for the August Olympics? Such a hectic indoor season was not a conventional way to prepare for the Olympic Games, but at least it enabled him to escape some of the training in the harsh Ohio winter conditions.

In March and April of 1964 Schul was competing outdoors almost every week. He ran 8:47 for Two Miles and 4:00.9 for the Mile. Then, still in April, he ran a 10,000 in 30:15 (second) and a 5,000 (first ahead of Billy Mills) in 13:59.4. After these good results that gave him confidence, he decide to opt for just the 5,000 in the Olympic Trials.

Olympic Build-up

|

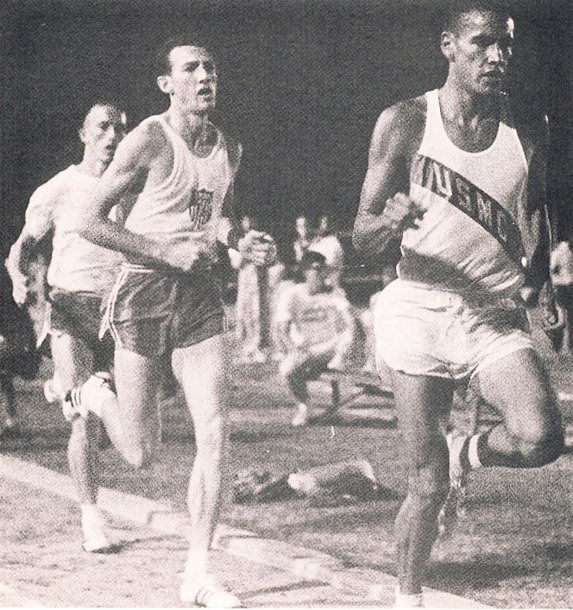

| Olympic Trials. Schul tracks Dellinger and Lindgren. |

In May he continued to race every weekend. Warming up for the major races, he ran four Mile races (best time was 4:01.6) and one Three Miles. His first major meet was the Compton 5,000 against Kidd, Beatty, Lindgren and Baillie. After a fast first mile (4:21) with Kidd leading, the race became tactical, and two miles was passed in 8:53. Then Schul took over. Running 65s, he soon broke up the field; only Baillie was with him at the bell. Schul made his effort with 300 to go and dropped the New Zealander. His last lap was 54.6 and his time of 13:38.0 was the fastest in the world for 1964 and an American record. Finally three winters’ hard work was paying dividends.

The next weekend he entered another Mile race in the hope of breaking 4:00. He managed to outsprint Mile specialist Cary Weisiger and ran 3:59.1. Schul was in the best form of his life. In the AAU 5,000 he needed his finishing kick to beat the tenacious Gerry Lindgren, winning in 13:56.2 to Lindgren’s 13:58.6. Lindgren was again an issue in the Olympic Trials, as was Bill Dellinger, who was rounding into form later than Schul. The three were out in front with three laps to go. Schul took the lead with 700 to go. With 300 to go, Dellinger stormed by. Schul responded, while Lindgren was dropped. Schul made his effort coming into the final straight and won in 14:10.8 ahead of Dellinger (14:11.4) and Lindgren (14:13.8).

|

| Schul follows Billy Mills on his way to aWR for Two Miles. George Young is third. |

Everything was going right. Even his allergies had got better: “What was so unbelievable was that my allergies were giving me less and less trouble. It seemed the more I ran and the better my conditioning, the healthier I became.” (Schul, p. 138) He now had two weeks of full training before the USA v USSR meet. This training went very well: “My workouts were the best I had ever done. Day after day I was doing more at faster speeds. Nothing could make me tired….” (Schul, p. 139)

Then suddenly his body rebelled, and he felt “stiff and tired.” In front of a sceptical Igloi, he tried a drastic solution: run himself to complete exhaustion. After doing this, he got a B12 injection from his doctor and felt better for the 5,000 against the USSR. Paired with Bill Dellinger, he faced Bolotnikov and Orentas. As they agreed beforehand, Schul and Dellinger waited until the last 300 to make their effort. They took full points with ease, Schul winning in 14:12.4 from Dellinger (14:14.2).

With two months to go to the Olympics, Schul settled down to his final training in California. He declined invitations to race in Europe, but he did run a Mile (3:58.9) and a 2:56.8 3/4 Mile. For a final tune-up he ran a Two Miles, attempting to break Jazy’s 8:29.6 WR. His friend George Young paced him through six laps (61, 2:05, 3:10, 4:14, 5:17, 6:22). Schul pressed on and made his final drive from 550. He passed the bell in 7:25 and hit the tape in a new WR of 8:26.4. A perfect last race before the Olympic 5,000.

Tokyo Olympics

|

| !964 Olympics: 230m to go. Jazy leads Norpoth and Schul. |

With his world-leading 13:38 clocking, Schul was definitely one of the favorites. He felt confident that he could beat Australian Ron Clarke with his sprint. A great worry was Michel Jazy of France, who had a devastating sprint himself. Still, he felt supremely confident that he could win the gold.

After a comfortable qualification run, Schul lined up for the 5,000 final on a rain-soaked track in 56f/13c degree temperature. Trying to get his legs comfortable in the cold, he stayed in the pack. Early on, disaster nearly hit him when Wiggs of Great Britain fell right in front of him. He jumped in time and just missed landing on the Brit’s leg. When Clarke upped the pace, the main contenders moved to the front of the chasing pack. Schul was soon fifth. He was able to respond to Clarke’s surges, but he chose not to react as quickly as Jazy did, preferring to conserve as much energy as possible.

|

| Tokyo Victory. Norpoth (209) is second and Dellinger (right) third. |

When Clarke surged again, Schul let the two Russians pass him and chase Clarke. Feeling supremely confident, he never worried that he might lose contact with Clarke. With six laps to go, Clarke was 15m ahead of him, but he felt so good he knew he could catch him if he needed to. When Clarke slowed again, Schul closed right up without any extra effort. He watched Clarke make another surge and then slow down again. Suddenly Jazy found himself in the lead.

With two laps to go, Schul made sure he was not boxed in by moving outside the first lane. Then on the back straight he moved up to fifth. Suddenly Dellinger flew by into the lead with 600 to go. Schul felt in control at this point and planned to go 300 out. But he got boxed in just when Jazy made his move with 380 to go. Luckily on the crown of the bend a gap opened up and Schul was able to turn it on. He quickly passed Dellinger and Dutov into third behind Norpoth. But a moment of doubt arose: he was running flat out but not gaining on Jazy. Had he lost the race?

But he couldn’t give up. Going into the turn and closing in on Norpoth, he realized he was gaining on Jazy and could see the Frenchman tying up. Betraying his difficulties, Jazy was looking back. Coming into the straight Schul moved onto the Frenchman’s shoulder. Running perfectly in his sprint mode, he quickly passed Jazy and moved on to a clear win and the gold medal. Behind him Norpoth, Dellinger and Jazy finished within 2.2 seconds. His last 300 on a soggy track was an amazing 38.7.

Battling Injuries

Unlike Bill Dellinger, Schul decided to continue his running career. His winter conditioning was hampered by a knee problem. He missed four full months before his knee healed. After this he desperately worked his way into a level of fitness for the AAU Three Miles. There were only a few weeks of conditioning before he began racing: “Though I didn’t win many races, the competition was good form me. (Schul, Autobiography II, p. 27) In early June he ran a promising time of 4:00.5 for the Mile. But then he had a setback, trying to finish fast in a race in Canada, he tore the same calf muscle that had plagued him in 1963. He had been running well with 300 to go and looked like running close to the American record of 13:11.4.

In the two weeks before the AAU, Schul received a lot of treatment and managed to get running again. He was on the start line for the Three Miles, with his calf taped. Ron Larrieu, the favorite, ran the first mile in a brisk 4:23. Four runners, including Schul, were still with him. Schul went in the lead for 660, but was feeling tired already. Larrieu again led at two miles (8:50.6). It took a huge mental effort for Schul to stay in contact with Larrieu and Neville Scott of New Zealand: “Now I concentrated on running each two hundred meters. At each point I would tell myself to stay for one more segment…. My body was one mass of hurt as I was using every last ounce of energy in my body. The way I felt I was not sure I could finish the race, but I willed my mind to banish those thoughts. Hang on, I kept telling myself, hang on.” (Schul, Autobiography II, p. 39)

The race got harder with 880 to go when Scott took the lead and increased the pace. But Schul was still with Scott and Larrieu at the bell: “My mind was racing; when would I try to win this? I can’t go at 300, I don’t have the strength, I must wait.” (Schul, Autobiography II, 39) Larrieu sprinted into the lead with 300 to go, but Scott and Schul were still with him. In a desperate finish in the last 100, first Scott and then Schul passed Larrieu, and then in the last strides of the race Schul inched ahead: “I thought this was the toughest race I had ever run and won. My body was devastated. The leg and the foot had held together and hadn’t given me any problems…. I had taken my body to the well and there were no reserves left. I marveled how I had been able to focus my mind on the task…. It was also apparent to me that this was the race of my life. As I walked around the area to cool down, I knew I never wanted to go through another race like that. It was almost too much to bear.” (Schul, Autobiography II, 39-40) He had run an American Record in 13:10.4, narrowly beating Neville Scott of New Zealand (13:10.8).

Europe 1965

After the AAU, Schul went to Europe where Clarke and Jazy were rewriting the record books. Only three days after his 13:10.4 he lined up for the World Games 5,000 in Helsinki. Clearly still recovering from his hard Three Miles race and also affected by jetlag, Schul was not able to run well. He was dropped on the fifth lap and finished 10th in 13:49.8. After this disappointment, he tried to race himself back into condition with eight relatively low-key races in 19 days. The most promising was a PB 1,500 in 3:40.7, leading the whole race except for the last 100, when Grelle, Tummler and Snell passed him.

The big race of his European tour was the 5,000 in the USA v USSR match. In Kiev he and Larrieu were again up against Bolotnikov, a runner Schul respected. The last lap was very exciting after Bolotnikov made his effort at the bell. Schul and Larrieu let him get a 3m lead with 300 to go, but Schul caught him before the last bend. However, Schul felt the tear in his calf again as he entered the straight and Bolotnikov came by. But the ever-tenacious Schul fought back and caught the Russian with a desperate dive at the tape. Despite an American appeal, the official result was as follows: 1. Bolotnikov 13:54.2; 2. Schul 13:54.4; 3. Larrieu 13:54.8. After another race where his calf gave way, Schul entered the World Student Games. Despite his injury, he just made the 5,000 final with a 6th place in his heat but then scratched. Back home he sought medical advice and understood that his injury would take a long time to heal. So he decided to retire from international competition. He was almost 28 years old.

Comeback

After a full year of rest—“To let my body heal”—Schul began running again. He started slowly, joining in with runners he was now coaching. Then he found he was running so well that he decided to make a comeback for the Mexico Olympics. Still fighting injuries, he managed to get back into the US top 8 for 5,000 early in 1968. But in the Olympic Trials an asthma attack prevented him from finishing higher than fifth. The comeback was over.

After this he stayed in the sport as a coach and masters competitor. At 49 he ran 10K in 33:55; at 60 he ran 39:55. In 2000 his first autobiography In the Long Run was published.

Conclusion

Although Bob Schul had to deal with allergies throughout his running career, he learned, before the availability of inhalers, to deal with his asthma attacks to the point where he found advantages in his handicap. He learned to control his body when he could hardly breathe and took this ability into his competitive track career. At times he claims his mind was outside his body, controlling it. Such dissociation enabled him to train hard and to race effectively. On the other side of the coin, his career did have some lucky breaks: he grew up on a farm where his body became used to hard work and running; he came into contact with Max Truex, the first American runner to show that Americans could be competitive internationally in distance races; he got to train under one of the great coaches in the world; and he won his Olympic gold in one of the few venues where allergies were not an issue. But above all, it was his personal qualities that made him an Olympic champion—his self-discipline and his competitive drive.

1 Comment