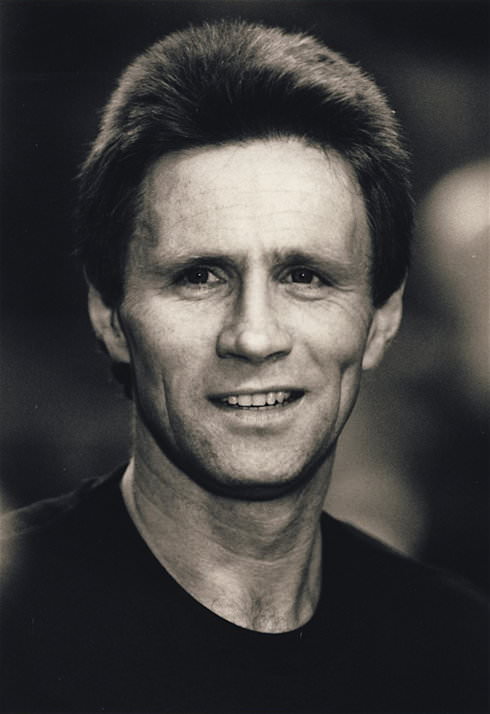

Eamonn Coghlan Profile

b. Nov 21, 1952

|

| Eamonn Coghlan: Claus Andersen's fine portrait. |

When he was 19, Eamonn Coghlan almost threw away his big chance to become an international runner. The previous year he had accepted an athletic scholarship from Villanova University to train with famed coach Jumbo Elliott and had left his native Dublin to live in the USA.

With no experience of life outside Dublin, he had a difficult time at Villanova. Culture shock, homesickness and academic difficulties hit him hard. As to running, he was also surprised by the severity of the track sessions (20x440 in 68 with 220 jog), double the amount of work he had done back in Ireland. Then he got injured. Coghlan described his first winter in the USA as “the unhappiest time of my young life.” (Eamonn Coghlan, Chairman of the Boards, Master of the Mile, p. 62)

One positive experience was his first run on the Villanova indoor track: “I was thrilled by the way it felt beneath my feet, by the way the springy pine boards responded to my steps. There was a fantastic feeling of speed and exhilaration as I ran through the turns and off the banks. I knew there and then that the boards were for me.” (Chairman, p. 63) But this one moment of exhilaration was not enough to assuage any of his unhappiness at Villanova.

After six months, in March of 1972, he was flown back to Ireland to compete for Ireland in the Junior international cross-country. Following the race, in which he ran badly, he surprised everyone by announcing he wasn’t going back to Villanova. And he didn’t.

Over the next few months his family and friends, from his father and his former coach to his girlfriend Yvonne, tried to persuade him to return, especially since Coach Elliot, against his normal policy, wanted Eamonn back. Normally, Elliott never accepted back runners who had quit, but he must have already seen something special in Coghlan. The persuasion finally worked, and in September 1972 Eamonn returned to Villanova. Within two years he reached international level with a 4:00.9 Mile time and achieved his first Senior selection for Ireland.

------------

Growing up in Dublin

Eamonn Coghlan was the fourth child born into a “typical hard-working middle-class family” in Dublin. (Chairman, p. 20) From an early age he showed a determination that was to serve him well later: “The first day of first grade, at the first opportunity, Coghlan ran home and put up such a protest that he was allowed to stay out of school for six months, until his best friend started.” (Kenny Moore, Best Efforts, p. 134). He was knock-kneed as a child and had to wear orthotic corrective shoes. Nevertheless, he spent all his spare time in a small local park. Like most of his friends he first dreamt of being a soccer pro. He also loved running errands: shopping for neighbours, distributing weekly soccer pools along the street, helping the milkman deliver, and carrying various garments to seamstresses for a local tailor. At the same time he often had to run fast to escape raiding gangs of street kids.

|

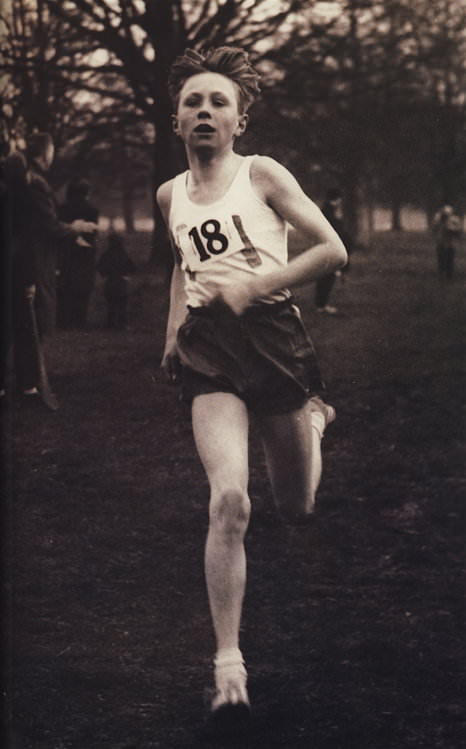

| Winning the Under-14 Dublin Cross-country Championships in 1967. |

Not surprisingly the benefits from all this activity soon became apparent when he started entering races. Just before his 12th birthday he won his first cross-country race. His interest then turned from soccer to cross-country, and he continued to win races. Just over two years later Gerry Farnan began coaching him. Thus began a 17-year relationship. Farnan, Coghlan said, “became closer to me than my father.” (Chairman, p. 35) By the time Eamonn was 16, Farnan was telling him that he would run for Ireland and win the Olympics. Farnan worked not only on strength but also on speed. Under his direction, Eamonn would do speed drills, “simulating the experience of coming off the last bend.” (Chairman, p. 40) This was crucial to Coghlan’s competitiveness as it developed what was to become his famous kick. Farnan was able to develop this kick despite the fact that Coghlan didn’t have “much natural speed.” (Chairman, p. 40)

How did Farnan develop Coghlan’s devastating kick? “We worked to change not just my style but also my mental outlook. I wanted to understand and visualize the process of switching gears instantly to that of a sprinter. He had me sprint without using my arms—just my legs in high knee lifts. He used a whistle, and when he blew it, I had to react immediately. The reflex speed was mental as much as it was physical. He hammered that into me until I understood.” (Chairman, p. 40) Thus Farnan helped Eamonn to improve the point where he was able to win a Villanova scholarship. And Farnan was also instrumental in helping to persuade him to return there after his first unhappy year.

Return to Villanova

After his first year at Villanova and his refusal to return in the spring of 1972, Coghlan realized that he had to knuckle down and make the most of his second chance. He had done a lot of maturing in the previous year and was now able to fit in socially and to deal with his academic difficulties: “Without the confidence Jumbo displayed in me, I’m certain I would have ended up back in Dublin without completing my degree and would have become a mere footnote in the Villanova track annals—another kid who couldn’t make the cut.” (Chairman, p. 70)

Jumbo Elliott emphasized routine, and Coghlan was now able to cope with the daily routine of “run, breakfast, classes, lunch, class, run, dinner, study.” (Chairman, p. 71) “It took a while to understand Jumbo even a little,” Coghlan wrote later. “He wanted to do all the thinking. It was his job to get us ready. It was our job to run. Guys who didn’t understand that didn’t do well. Those who did, and accepted it, and went with him, did fine.” (Chairman, p. 138) Eamonn gradually built up his mileage and avoided injury. After a Christmas break in Ireland, he ran his first Mile on the boards and won in 4:18. But Elliott was in no hurry for results. In preparation of the 1973 outdoor season, Elliott concentrated on his athletes doing repetition quarters—twenty almost every day. Then he raced Coghlan a lot, often asking him to run several events at relay meets. Coghlan was the lead-off for the Villanova team in the Penn 4xMile relay. His 4:09 PB in this race was the highlight of his second year at Villanova, and he went home for the summer, having passed his exams, “a new runner and a new man.” (Chairman, p. 76)

Breakthrough

After another fall’s training, Elliott thought the 21-year-old Coghlan was ready for top competition in the 1974 indoor season. At a February meet in Cleveland he fought Dave Wottle to the line, finishing second in a 4:03.9 PB. Then he won the IC4A 800 indoor title in 1:51.9. Outdoors he raced regularly for Villanova and dropped his Mile time to 4:00.9. Back in Ireland for the summer he won his first Irish title (800 in 1:50.2) but just failed to qualify for the European 1,500 despite running a 3:41.9 PB. He also ran his first international for Ireland in Germany—and won. At the last minute he was sent to the Euros in Rome after all--for the 5,000. Although he didn’t qualify for the final (7th in his heat with 14:29.6), he got his first taste of what it was like to run in a major meet and returned to Villanova for his third year with even more determination to succeed.

Eight Seconds Faster

|

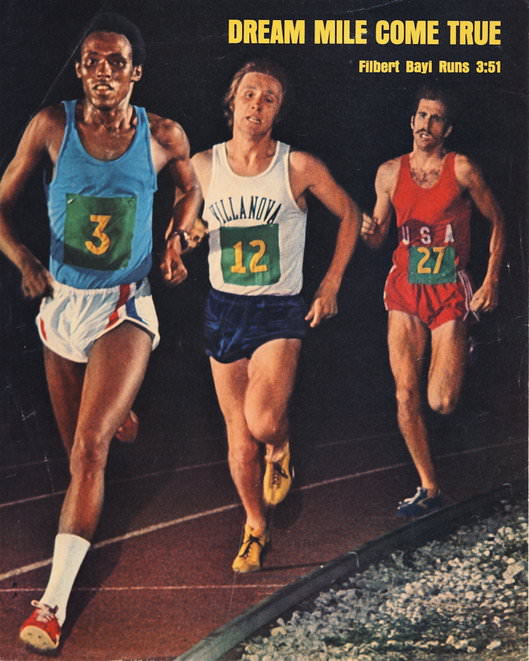

| On the cover of Sports Illustrated. ChasingBayi, with Liquori in third. |

By the time the 1975 outdoor season began, Coghlan was more than ready to break four minutes. He first did it twice unofficially in relay legs, before finally breaking the barrier on May 10. His good form led to an invitation to run in Jamaica in the Dream Mile, but before he went there he PB-ed in Pittsburgh with 3:56.2.

In Jamaica the in-form Tanzanian Filbert Bayi was rumoured to be going after a world record. Since he always raced from the front, there was a strong prospect of a fast race. As well, there were Marty Liquori and Rick Wohlhuter to push him. But Bayi went off too fast. After the first lap Coghlan (59.1) in second was already 15yds behind the Tanzanian (56.9). Coghlan was still 10 yards behind at 880 (Bayi, 1:56.6). But on the third lap, he caught Bayi and approaching the bell even passed Bayi for a few strides. At the bell (2:55.3), Bayi was on schedule for the world record, and Coghlan was in the hunt too. But then Bayi surged away and Liquori moved up to Coghlan. On the back straight, as Coghlan tried to hold off Liquori, Bayi’s lead was reduced to a yard. But Bayi had yet another gear and moved away again, while Liquori passed Coghlan. In the last 150, the order remained the same. Bayi (3:51.0) just managed to beat the world record, while the more experienced Liquori (3:52.2) held off Coghlan (3:53.3). Coghlan had improved his PB yet again and set a new European record to boot.

Olympic Thoughts

Now he had really arrived. He was featured on the cover of Sports Illustrated, trailing Bayi and with Liquori in his wake. And to cap it all, his 1975 North American season ended with an NCAA Mile title. Back home in Ireland for the summer, he raced a few times, but he was tired and past his peak.

Then it was back to Villanova for his final year o face some hard studying to graduate. Still, he was now an Olympic prospect, and Montreal was less than a year away. Taking a long-term approach, he focused on building his mileage for the rest of 1975. Then in the new year he competed successfully indoors and then outdoors on the college circuit. He won the both the NCAA and AAU 1,500 titles and then stayed on at Villanova to put the final touches on his conditioning for Montreal. A last-minute 800 time-trial in 1:48.5 showed he had speed, though not as much as his main Olympic competitors.

While his Irish supporters were touting his gold-medal chances—especially after the African boycott that eliminated Bayi—Ron Delany, the 1956 gold medalist, tempered this optimism, arguing that a bronze was the highest that could be expected of Coghlan. Delany was well aware that the 23-year-old had little international experience to cope with the enormous stresses of Olympic competition.

Montreal 1,500

Eamonn won his heat in the preliminary round with 3:39.7. Then he won his semi too (3:38.6) with an impressive kick. Boosted by the Irish media, he was now full of confidence that his final kick would work for him in the final. Nevertheless, he knew that he was facing three runners with much faster 800 times: Walker (1:44), Van Damme(1:43), and Wolhuter (1:43). In fact, Jumbo Elliott, well aware of the power of these three runners, advised Coghlan not to let the race get too slow.

|

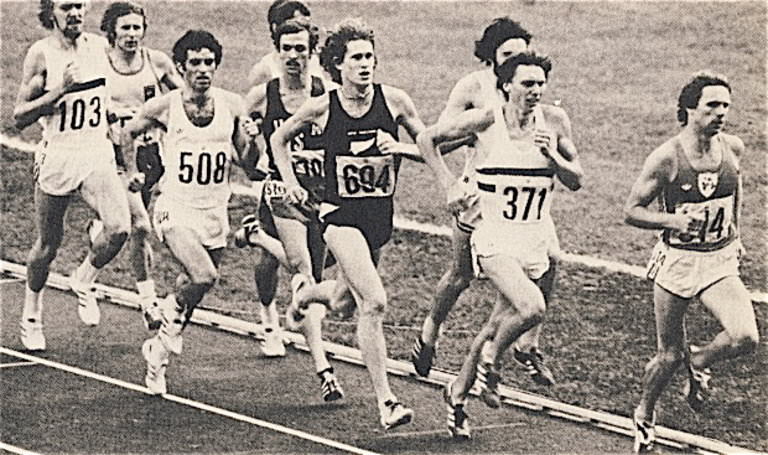

| Coghlan leads the Montreal 1,500 final from Moorcroft,Clement (hidden) and Walker. |

As he lined up for the final in front of 70,000 spectators, he “felt like a little boy amongst men.” (Chairman, p. 102) His start went well, and he settled in the behind Walker—just where he wanted to be. All was fine until he heard the time of the first lap: 62-63. Too slow. On the back straight he reacted quickly, too quickly, and sprinted through the field to the front. As soon as he was in the lead he looked round to see Walker shadowing him: “At that instant I realized that I might already have set myself up to be the sacrificial lamb.” (Chairman, p. 103)

Wishing someone would pass him, Coghlan cruised through 800 in 2:03 and 1,200 in 3:01 with Walker hot on his heels and pushing him to run a little faster. He had held off Walker’s attempt to pass at the bell, but could not do so again with 300 to go. He had to stay with Walker and to do so he moved into his top gear much too soon. With 200 to go, Van Damme passed him. Then he had to fight to hold off Wolhuter round the bend. In the straight he went after Walker and Van Damme, but to no avail. Although he didn’t lose ground, he couldn’t make any impression, and with 30m to go, the German Wellmann came past him on the inside. He was fourth. Only 0.5 of a second separated the first five. So close! His undoing was his inexperience and lack of confidence; his fault had been rushing to the front so early, clearly reacting to Coach Elliott’s warning about a slow race. Also, he appeared vulnerable to the long drawn-out attack from 300 to 400 out. Such a tactic had neutralized his late kick.

Career Runner and Tourism Rep

Now a university graduate and a married man, Coghlan had to look for a job. He was courted by the pro track WTA organization but declined their offer. He tried a sales job with a bank, but finally decided that the best way to earn a living was to run the USA indoor circuit. So in January 1977 he went back to the USA. After obtaining a job with the Irish Tourism Board, he won three of his four indoor races, one of which was his first Wanamaker Mile victory. In the summer, his big race was against John Walker on the new tartan track in Dublin. Coghlan again found himself in the lead at the bell (2:58.1) and had no answer to Walker’s final 100: 1. Walker 3:52.0; 2. Coghlan 3:53.4. These were the world’s two fastest times for 1977, but really Coghlan’s outdoor season was not a very successful one. He did win the British Championships in 3:43.02, but lost Walker again in Gateshead (5th in 3:59.7). Then in Edinburgh he was 13th in an August race with 4:07.2.

Since his job allowed him time off for competition, he journeyed Down Under in January 1978 to meet his nemesis Walker. But before their first race, Coghlan beat Moorcroft and Hermens over 3,000 and Dixon and Quax over Two Miles. Then he took Walker’s scalp twice, once in Sydney and once in Christchurch. But in their final meeting, after the two rivals had socialized, Walker finally got the better of Coghlan (3:56.4 to 3:57.4). The two next met in Los Angeles on the indoor track. This time Coghlan just managed to pass the Kiwi in the last few yards. So in their four previous races, Coghlan had won three. Where Coghlan had always looked up to the New Zealander, he now felt he “had his number.” (Chairman, p. 119)

Moving up Distances

Coghlan was now being coached again by his former coach Gerry Farnan. They established a long-term plan for the Moscow Olympics. The idea was to keep racing over the Mile but to train for the 5,000. That meant upping his weekly mileage to 100. It would require twice-a-day training six days a week and a 23-mile run on Sundays. Two of his staple sessions were now 8x1200 and 4x3200—no more Jumbo Elliott quarters!

After the busy time Down Under in early 1978, Coghlan waited until September to peak for the outdoor season. The target was the European Championships in Prague. His main opponent was the precocious Steve Ovett, who had been virtually unbeatable in the European summer. Three days before the 1,500 final, the Brit had finished second in the 800 with a PB of 1:44.09 behind Olaf Beyer. Also in the Euro 1,500 final were Moorcroft, Wessinghage, Plachy.

The pace was fast: 57.5, 1:57.1, 2:57.1. Coghlan ran in the pack for the first two laps; then with just over a lap to go, he found himself in the lead. Unwilling to do any leading, he let the field past only to get badly boxed in. He stayed boxed round the penultimate bend and was still trapped when he saw Ovett start his burst around the last curve. As Coghlan tells it, “With 135m to go, a small chink of light appeared and allowed me to force my way out of trouble. I surged past Wessinghage and Moorcroft and went off in chase of Ovett, who was at that point out of sight and a shoo-in for gold.” (Chairman, p. 121) Although Coghlan was the fastest finisher, Ovett’s lead was still a whole second at the tape: 1. Ovett 3:35.59; 2. Coghlan 3:36.57; 3. Moorcoft 3:36.70; 4. Wessinghage 3:37.19. Still, his silver was his first medal at a major championship.

Indoor Successes and World Record

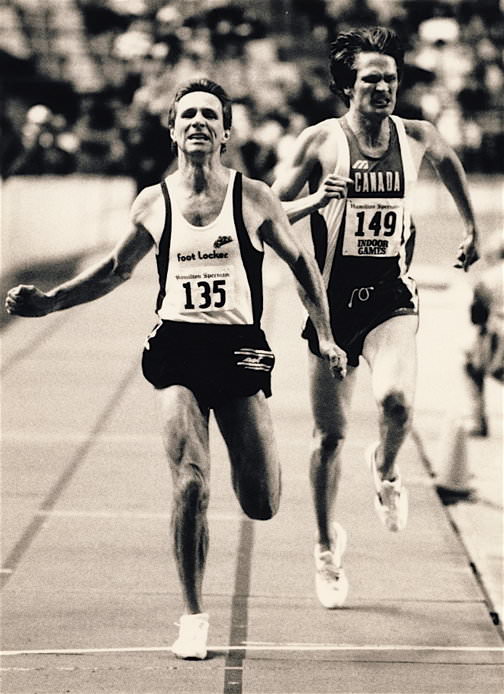

|

| Coghlan holds off Graeme Fell in an indoor race in Canada. (Claus Andersen photo) |

Coghlan decided to spend his fall 1979 training in a warm climate and moved to San Diego. This environment worked well for him: in the 1980 indoor season, he had consecutive victories in LA (3:56.1), San Francisco (3,000 in 7:57),Toronto (3:58.0) and Edmonton (3:57.7). In New York, he continued with another victory in the Wanamaker Mile against a top field (3:55.) He was clearly in good enough form to attack the indoor Mile WR on the fast San Diego track. On February 16, he lined up with Steve Scott, Steve Lacy and Paul Cummings. After being towed to the 3/4 mark in 2:56.5, he took the lead. First Lacy and then Scott challenged him over the last 400, but he held on to win in 3:52.6, well ahead of Buerkle’s 3:54.93 WR clocking.

Two weeks later he won the European Indoor 1,500 from John Robson and Wessinghage in a slow tactical race. Next, in achieving a fine tactical victory over Walker and Scott in Philadelphia, he set a new outdoor PB of 3:52.88. The European summer season saw Coghlan still in good form. He started with a close race against Steve Scott in Stockholm, just losing 3:55.96 to 3:56.24. Next he ran a fast 7:39.1 3,000 to win in Oslo. He was ready for the big one: the Bislett Golden Mile. All the top milers was there: Walker, Scott, Wessinghage, Moorcroft, Masback. Also in the field was 800 runner Seb Coe. And it was Coe who surprised everyone. After Steve Lacy had taken the field through two laps in 1:54.5, Steve Scott took up the running and only Coe was willing to go with him. Clearly Scott’s aim was to neutralize Coghlan’s finishing kick, which had destroyed him in Philadelphia. Soon the duo had an 8m lead over Coghlan and Wessinghage. Coghlan was now passed by Walker, and in the next half lap he was back in sixth. From this position his kick could only move him up to fourth at the tape. Coe won with a 3:48.95 WR. Then came Scott (3:51.11), Masback (3:52.02) and Coghlan himself in a PB 3:52.45. He again was the fastest finisher, but again the race had been decided long before the last 100.

Moscow Focus

Coghlan’s 1980 indoor season was extremely successful; he took all his races but the last. He won the Wanamaker Mile, holding off a strong Masback and then won the most competitive Mile of the season in Los Angeles with 3:52.9, only 0.3 outside his WR. In this race he beat Scott, Bayi, Masback and Wessinghage. Bayi, with a 3:55.5, managed to avenge this defeat a week later in San Diego, where the first four runners finished within a second. Coghlan (3:55.7) held off Walker and Wessinghage for second.

So Coghlan completed his indoor season with high hopes for the Olympics. He clearly still had his speed, and he had been working hard on his 5,000 strength. But adversity was ahead. Fine-tuning for Moscow, he ran seven races in nine days—“madness” he called it later. (Chairman, p. 130) This acerbated his shin soreness (later diagnosed as a stress fracture). Then just 19 days before he left for Moscow, he suffered severe food poisoning. This left him feeling weak right through the Olympics. He struggled through his heat and “miraculously” managed third place in his semi.

In the 5,000 Olympic final, his main opponent was Yifter. Also dangerous were Nyambui, Ryffel and Treacy. “From the moment the race started,” he wrote later, “I felt utterly depleted. My legs felt heavy and there was no bounce in my stride. It was like driving on two flat tires.” (Chairman, p. 133) Fortunately for him, the pace was slow, so he was still in the race with 800 to go. At the bell the field was still bunched: “It seemed like they were playing into my hands…. I was cruising still strongly in the hunt in an attacking position safe on the outside.” (Chairman, p. 133)

Round the penultimate bend, he managed to keep Yifter boxed in behind his Ethiopian team-mate Kedir, but on the back straight Kedir moved out and let Yifter through on the inside into the lead. Coghlan passed him, but Yifter immediately took back the lead with 250 to go. This put Coghlan into trouble; he was running flat out to stay with the Ethiopian. Round the last bend Nyambui came by and then Maaninka caught him near the tape. Fourth again, just as in Montreal. Coghlan took this badly: “Finishing fourth in the Olympics is regarded as the worst possible position. To finish fourth on two occasions almost seems absurd. And like all world-class sports people who have failed to translate their raw talent into victory or a medal, it’s a burden that I have to deal with virtually every day of my life.” (Chairman, p. 135)

Considering Retirement

Depressed after his second fourth-place Olympic finish, Coghlan was ready to quit. But Gerry Farnan talked him out of retirement: “You’re still a young men and there is plenty of life left in those legs. Go back to America and live full-time. Go there and make some real money…” (Chairman, p. 134) Making money from running was not difficult now, for the under-the-table payments that had long been the practice in track were no longer needed. Prize money and appearance fees were now an accepted part of track and field. Following Farnan’s suggestion, Coghlan managed to transfer his job with the Irish Tourist Board to New York. So this made the move across the Atlantic more attractive.

Farnan sent off his 27-year-old protégé with four new goals: to run the first sub-3:50 indoor Mile, to win the 1982 Euro 5,000, to win the 1983 Worlds 5,000 and to win gold in the 1984 Olympics.

But this four-year plan didn’t start well. It took him months to recover from his summer illness, so he was not at his best when he began the 1981 indoor season. Although soundly beaten by Scott and Paige in his first race, he still ran 3:59.1. Three weeks later he was second to Scott with a 3:54.3, but then he beat Scott and won his fourth Wanamaker Mile in 3:53.0. His first goal of a sub-3:50 looked possible, and a race was set up on the fast San Diego track against Scott and Walker. Before the race, Walker told Kenny Moore, “Eamonn is ready for the world record. He has been running great times on bad tracks.” (SI, March 2, 1981)

Phil Kane took the field through 800 in 1:55.5, with Scott and Coghlan a second back. Scott took over the lead to pass 1320 in 2:55.4. Walker had moved up and was with Coghlan just behind Scott. Then Coghlan took advantage of a wide turn by Walker and in a flash was up into second. As planned, Coghlan passed Scott early with two laps to go: “Steve had seen me sprint the last lap or a lap and a half at most in our races this year. I figured going with two laps left would take him by surprise.” (SI, March 2, 1981) Scott stayed with him for a while but could not hold him in the last half lap: 1. Coghlan 3:50.6; 2. Scott 3:51.8; 3. Walker 3:52.8. Coghlan had set indoor world records for both 1,500 (3:35.6) and the Mile (3:50.6). But he had missed the sub-3:50.

After this race, Coghlan explained the benefits of the 5,000 training he had been using: “Over the last three years I trained for the 5,000, using my Mile racing as part of the preparation for my 5,000…. I reverted back to mile-type training especially for this past indoor season, and I ended up running 3:50.6. So the strength from the 5,000 training has been a tremendous asset to my background.” (The Milers, p. 460)

Injuries and a Year Lost

Although he went to Europe for the 1981 outdoor season, he wasn’t a major force. His best run was his win in the 5,000 in the IAAF World Cup. The American indoor season was now his main focus. However, the shin soreness problem came back with a vengeance in January of 1982, just as the season was starting. He had to rest six weeks with a stress fracture in his tibia. Still, the problem wasn’t over then: “It was my first taste of serious injury, and it was to effectively keep me from running for an entire year.” (Chairman, p. 145) As soon as he began running again, Coghlan felt a sharp pain in his achilles. This pain would not go away, and in desperation he went to Germany for radiation treatment.

Finally in the fall of 1982 he managed to return to regular training. After the trauma of a serious injury, he was more focused than ever. While one of Farnan’s goals could not now be achieved (the 1982 Euro title), there were still three others to work towards.

Under 3:50 Indoors

The 1983 indoor season found him in good enough form to consider going for a sub-3:50 Mile. He won his fifth Wanamaker Mile in a fast 3:54.4, with Wessinghage 3.5 seconds back in second place. But then his father, whom Coghlan had brought over to watch the indoor season, died suddenly. Coghlan’s season was on hold. After the funeral in Ireland, he was back in New York with the words of his bereaved mother in his ears: “All you can do now is go back to America and break that world record. That’s what would make him happy.” (Chairman, p. 152)

He chose the US Olympic Invitational meet for his planned WR attempt. His main competition was to be Abascal of Spain, Ray Flynn and Steve Scott. Scott was skeptical about a sub-3:50: “For Eamonn to break the record, somebody’s going to have to push him through three-quarters. Just who’s going to do that?” (SI, March 7, 1983) Eamonn was relying on Ross Donoghue to do that. Donoghue took them through in the half mile in 1:56 but then unexpectedly dropped out. Coghlan had half the race to run from the front—something Scott didn’t think he could do. Coghlan describes what he did next: “I ran close to the inside curb. I leaned very low on the turns, catapulted off the steep banks into the straights, and simply flowed painlessly along. I kept going and going, putting more pressure, running as though I was a runaway train.” (Chairman, p. 155)

He passed 1320 in 2:54.8. It wasn’t until two laps to go that he felt someone on his shoulder. All he could do was to keep going: “Sprinting my way through that last lap was the most exhilarating rush of speed I ever experienced—on any track—any time. I felt like I was running on a cushion of air. There was no pain, no distress, nothing holding me back. I could put my foot on the gas and go at will. There was just a positive flow of energy pushing me effortlessly all the way beyond the finish line.” (Chairman, p. 155-6) From this description it’s clear he was in a highly emotional state for this race. As he finished in a new WR time of 3:49.78, the first indoor Mile under 3:50, he thought of his father: “That was for you, Da.” (Chairman, p. 156)

Indeed, Eamonn Coghlan was Chairman of the Boards, as the media were calling him. He had perfected the art of indoor running. Quoted in The Milers, Marty Liquori said, “[Coghlan] has the best acceleration of anybody. He can reach full speed in five or six steps. He can pass someone before they even know what has happened.” (p. 489) But for this first sub 3:50, as Cordner Nelson and Roberto Quercetani pointed out in The Milers, Coghlan used a different tactic from his usual fast finish: he did it from the front.

One Farnan goal achieved; two more to go.

Worlds 1983

Coghlan’s none too friendly rivalry with Scott over the Mile continued outdoors. Scott drew first blood with a win in San Jose, 3:55.37 to 3:56.46. But two weeks later Coghlan was the winner, 3:52.52 to 3:52.53. It was a tight race with Coghlan just catching Scott at the tape.

But the Worlds 5,000 in Helsinki was the main outdoor focus. To that end he ran the 5,000 at the Prefontaine meet, winning in 13:23.53 with a 52.6 last lap. His good form continued over in Europe: a 3:51.9 outdoor PR in the Mile (finishing 5th), a 7:46.40 3,000 victory, and a 13:31.67 victory over 5,000. For the last two weeks before the Worlds, he tapered down, doing little more than jog. He was ready for the third of the four goals set by Farnan.

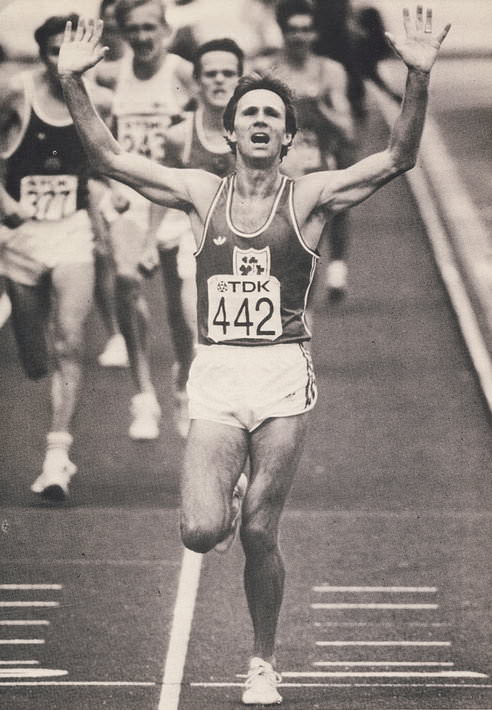

|

| 1983 World Champion for 5,000. |

An in-form Coghlan lined up for the final full of positive thoughts, fired by a recent reading of The Winning Edge by Denis Waitley: “I’d broken the race down into three stages. Stage one would consist of the first seven laps. Stage two would be getting from six laps to go to just four laps left. And when stage three arrived, I was going to be a miler again, and no one in this field could beat me over a Mile.” (Chairman, p. 165)

He stayed safe for the first half of the race, near the back but not boxed in, and found the pace “reasonably comfortable.” As soon as stage two arrived, he moved up the field towards Dmitriyev and Padilla in the front, tucking in behind Wessinghage, whom he considered the main danger. With 3 1/2 laps to go, Dmitriyev took off, but Coghlan wasn’t worried. With two laps to go the Russian had a good lead, and Wessinghage clearly wasn’t running well. So without any panic, Coghlan went after Dmitriyev. He wasn’t even worried at the bell when the lead was still 20m.

It was now a two-man race. He caught the Russian on the back straight: “I was feeling so good there and then that I could have gone right by. I was on a high.” (Chairman, p. 166) But he disciplined himself to wait round the last bend, even though he could see the Russian’s legs begin to buckle. Coming off the final bend, he went by. His margin at the end wasn’t great, but he was a clear winner. He was the world champion: 1. Coghlan 13:28.53; 2. Schildauer 13:30.20; 3. Vainio 13:30.34; 4. Dmitriyev 13:30.38. In this race Coghlan showed confidence in his ability: he didn’t panic as had done previously in some of his major races, and he showed great patience in timing his final effort.

This Worlds win was the pinnacle of Coghlan’s outdoor career, and it came late, when he was 30. But his two Olympic “failures” had long rankled him: “Having finished fourth in two straight Olympics, I’d disappointed [the people of Ireland] and disappointed myself, but this went some way to make up for it. This time I’d shown that I could do it when it counted.” (Chairman, p. 168) No mention here of all the times when he did do it when it counted—indoors!

LA

There was only one of Farnan’s four goals left: a gold in the 1984 Olympics. By this time Coghlan was a true running pro, earning $500,000 a year. Such was his prestige that he was able to quit his job at the Irish Tourist Board and still keep his salary solely by agreeing to wear a Discover Ireland vest in competition. Buoyed by his Worlds win, he looked ahead confidently.

But then he hit another roadblock: a tibia stress fracture on his other leg. He desperately tried to keep fit by cycling, swimming and even by stimulating his muscles with electric-shock treatment. When the summer of 1984 came, it became clear that his hopes of running in LA were gone. Nevertheless, he went over to Ireland for the trials, despite “excruciating pain” when running. And that pain forced him to drop out at the halfway point of the 5,000. He did go to LA---but as a commentator—and watched Aouita win his event: “My only consolation was that I doubted very much, after witnessing his scintillating performance, that I’d have been able to match him, but felt confident that I could have been among the medals.” (Chairman, p. 174)

Miles to Go

But Coghlan’s running career was far from over. Although he experienced “just one injury after another,” (Chairman, p. 176) and although his body was telling him to stop, his desire to compete was still strong. And amazingly, even to himself, he was able to run two 3:53 Miles, one of them being his sixth Wanamaker victory. Then injuries ended his 1985 indoor season and continued through the summer. Against his better judgment, he was persuaded into running one race in Ireland: an attempt on the WR for 4xMile. Despite being the only member of the Irish team not to break the 4:00 barrier, he became a proud world-record-holder with Ray Flynn, Frank O’Mara and Marcus O’Sullivan. They clocked 15:49.08.

The up-and-coming O’Sullivan began beating Coghlan in the 1986 indoor season, winning both the Sunkist Mile in LA and the Wanamaker. Coghlan was not at his best as he had been experimenting with a high carbo diet that left him 14lbs lighter than normal.

His goal for the 1987 indoor season was to win the Wanamaker Mile for the seventh time and thus break Glenn Cunningham’s record, which he’d already equaled. Not only was the dangerous O’Sullivan beside him on the start line, and so was his old rival Steve Scott. And then there were Abascal and Olympic champ Steve Ovett . It was a daunting field. Coghlan, still confident in his change of speed, waited until the back straight of the last lap to jump from fourth to first. In that short straight he passed O’Sullivan, Abascal and Flynn, all of whom were going flat out. He won in 3:55.91 and notched his seventh record-breaking Wanamaker title. Bearing in mind the stiff competition and the state of Coghlan’s 34-year-old legs, this race must rank up with his finest.

On and On

And yet, and yet, there was to be one more major achievement. But that was several years ahead. Meanwhile, after his seventh Wanamaker win, Coghlan managed an indoor WR for the rare 2,000 event: 4:54.07. His next big meet was the Indoor Worlds in Indianapolis. He was tripped and fell on the second lap of the heats and just failed to qualify. New injuries, old injuries and even accidents increasingly slowed his running. So he began to focus on a career as a communications coach for business executives. Still, in 1988 he just managed to qualify for the Seoul Olympics. He was 35 and not in his best shape. In the 5,000 he got through his heat but was 15th out of 16 in his semi.

His running now took a back seat as he focused on his new career. And when two years later in 1990 he decided to make a comeback, there was a lot of skepticism. His indoor season started with three low-key wins, after which he could only make fifth in the Wanamaker Mile. His 37-year-old body was not in the best shape: “My legs were weary,” he wrote. (Chairman, p. 205) In May of 1990 he decided to return to Ireland. There he landed a job with BLE, the Irish athletic organization. However, this job proved stressful and he eventually resigned. Next, looking for “a cathartic outlet for my energies,” (Chairman, p. 218) he decided to go back to running and try to become the first Master to break 4:00. This was certainly a goal that Farnan had never considered! The Masters WR for the indoor Mile was only 4:13.

Yet Another Goal

Now out of competition for a couple of years, he developed a two-year plan to break 4:00 again. He’d already done it 77 times; the 78th would be the most difficult. John Walker, who had run even more sub-4s than Coghlan, looked like his main challenger as he was still running well at 38. Steve Scott and David Moorcroft were two other likely ones to go sub-4 once they hit 40. As Eamonn began training seriously, he decided to run the fall New York Marathon, and he surprised a lot of people with a 2:25.14 for 41st place after only a few months’ training. This run provided him with “the foundation upon which to build my training throughout 1992.” (Chairman, p. 228)

Coghlan’s chances looked even better when Walker retired because of injury. He was also encouraged by a victory in an Edinburgh Mile road race, beating Scott, Maree and Nick Rose with 4:06. Not surprisingly he encountered more injury problems. However, he kept training and ran his first indoor Mile in the Millrose Games, breaking the Masters record of 4:13 with a 4:08. At Madison Square Gardens he ran 4:05.3, but his legs didn’t feel right. The speed had gone. Nevertheless, just two days later he got down to 4:03.28. Finally, in the US indoor championships he ran 4:01.2, breaking the Master's WR for the indoor Mile for the fourth time. This was his last attempt in the 1993 indoor season. However, he hadn’t given up on his last goal.

Waiting for the 1994 US indoor season was a worry as David Moorcroft, now 40, was running well. The English runner actually went to Dublin that summer to break 4:00 (Coghlan wouldn’t go to watch!). Moorcroft was on pace for 1320 but then faded to 4:02.6. Battling injuries almost all the time, Eamonn still managed to get in shape. His big attempt was to be in the Masters’ Mile at the Millrose Games. He won but ran only 4:04.55. Two nights later he ran an encouraging 4:03.23. It was difficult for him to get good races, but finally he found a meet in Boston that would put on a Masters’ Mile. Stanley Redwine was the chosen rabbit; he had done well in this role in Europe. He led Coghlan through 880 in 1:59; the plan was going smoothly. But Coghlan was in for a shock when Redwine dropped out a lap earlier than planned. After the initial shock, Coghlan ploughed on: “With 150 yards to go my legs were buckling. They were all over the place, totally out of control, but the noise of the crowd told me I was on schedule. It was almost an out-of-body experience.” (Chairman, p. 251)

The watches stopped at 3:58.15. In his autobiography, Coghlan has described his feelings after this great run: “It was the most profound running experience of my life—different to anything that had gone before…to me it was an emotional and physical triumph beyond my wildest expectations. Nothing compared to the feeling of ecstasy that enveloped me when I crossed that line.” (Chairman, p. 251) It had been nearly seven years since he had last run sub-4. And those seven years had been fraught with setbacks, especially injuries. His self-belief and perseverance had been rewarded. And his running career was complete. Not even the offer of a $50,000 appearance fee would tempt him to compete again.

Conclusion

Although Eamonn Coghlan possessed a race-winning kick that was virtually unanswerable, he will probably be remembered first as a record breaker. True, his competitive record indoors was close to 100%, with his amazing seven wins in the Wanamaker Mile a standout. But his outdoor record, despite his Worlds 5,000 title, is not as impressive. He was a fine outdoor runner, but his vulnerability to a prolonged attack from 300-400 lost him some important outdoor races. He was very close to two Olympic golds, but each time he was unable stay with the pace over the last lap.

So this great Irish runner will probably be remembered for running the first sub-3:50 Mile indoors and for being the first Masters runner to break 4:00. These two achievements are testament to his tenacity and perseverance.

3 Comments