1970 Commonwealth Games

Meadowbank Stadium, Edinburgh, Scotland, July 17-25

There were two big changes from the previous 1966 Games in Jamaica. First, the distances were metric for first time. Second, the track was a synthetic all-weather track. No more cinders!

800

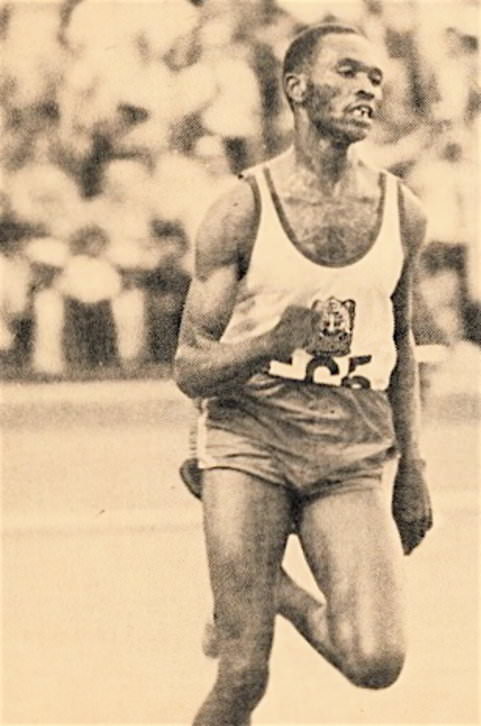

Olympic Champion Ralph Doubell of Australia was the clear favorite. In the previous Commonwealth Games he had been sixth. Another hopeful was Benedict Cayenne, who had finished 8th behind Doubell in the 1968 Olympic 800 final. The Trinidadian had run a fast 1:46.83 in the semifinal.

This race came alive on the back straight of the second lap when John Davies shook up the field with a burst. At this point Doubell lost contact. Robert Ouko, a Kenyan runner studying in the USA, matched the burst and moved past Davies on the bend and won comfortably. His last 200 was timed at 25.7. Behind him there was a close tussle between Cayenne and Canadian Bill Smart. The Trinidadian was only 1/100th of a second ahead for the silver. Both Cayenne and Smart won their only major-games medals. Doubell later explained his disappointing performance: “The fire in the belly had gone.” Australia and England had five runners in this final, but none won a medal.

1. Robert Ouko KEN 1:46.89; 2. Benedict Cayenne TRI 1:47.42; 3. Bill Smart CAN 1:47.43; 4. Chris Fisher AUS 1:47.78; 5. John Davies ENG 1:47.79; 6. Ralph Doubell AUS 1:47.86.

1,500

Jipchoge Keino was the clear favorite for the 1,500 title. Past performances indicated that there was really no one in the field who could get close to him. European champion John Whetton had been fifth behind him in the Mexico Olympics, but the Englishman had been an incredible nine seconds slower. Kiwi Dick Quax had beaten the Kenyan earlier in the year in New Zealand, but few thought he could do it again in a major race. Brendan Foster had recently run close to Keino in a Two Miles (8:29.0 to 8:30.8), but the young English runner was still quite inexperienced in international racing.

There was, however, one complication. Unknown to the crowd and to the other competitors, Keino had received two death threats, one by letter and one by phone. The threats were that he would be shot by a telescopic rifle if he won the race.

|

| Keino the courageous. |

Despite the cold wind, it wasn’t long before Keino was in the lead. The early pace was set by Quax, but at 300 the Kenyan moved into second place. He was in the lead at 400 (57.6) and reached 800 in 1:55.0. Only one runner was able to stay with him—Dick Quax. At the bell, the two were 40m ahead the next group of four (Peter Stewart, McCafferty, Whetton and Foster). The 22-year-old New Zealander was clearly running the race of his life, for he was still with Keino at 1,200, which was passed in an electric 2:52.

Keino opened up a small gap round the last bend, but Quax held on gamely, and he was still within striking distance coming into the straight. But then Keino accelerated, and although tying up in the last 40m, he managed to build up a 1.5-second advantage at the tape. Despite the wind, Keino and Quax’s times ranked them second and third fastest of the year. Behind them there was a big battle for the bronze medal. Foster ran much of the last lap behind Stewart, McCafferty and Whetton, waiting until the last straight to make his effort: “I managed to get through them, and held off Whetton, who tried to come back past me on the outside. Peter Stewart, urged on by the Scottish crowd, came at me hard on the inside and we both crossed the finishing line together.” (Brendan Foster, Cliff Temple, Brendan Foster, p. 49) Foster just managed to get third place by leaning into the tape; both he and Stewart were given the same time. Whetton was half a second back in fifth.

|

| Just into the straight, Quaxwas still close to Keino. |

The courage of Keino was evident not only in his defiance of the death threat by winning but also in his completion of a victory lap afterwards. He nonchalantly told the Times reporter that he wasn’t thinking of records, just of winning, when surely the thoughts of a gunshot were in his mind too. Courage too could be applied to Quax’s performance; no one else dared run with the great Kenyan. And Foster’s bronze was the start of a stellar career in middle-distance racing.

1. Kip Keino KEN 3:36.6; 2. Dick Quax NZL 3:38.1; 3. Brendan Foster ENG 3:40.6; 4. Peter Stewart SCO 3:40.6; 5. John Whetton ENG 3:41.2; 6. Ian McCafferty SCO 3:42.2.

5,000

Prospects

This 5,000 race had all the qualities of a Great Race. It took place in a major games, it fielded some of the world’s finest middle-distance runners, it recorded four of eight all-time fastest clockings, it involved some intriguing tactics and it ended up with a very exciting last two laps. Roberto Quercetani considered that this race had “hottest finish in the history of the event.” (Track & Field News, July, 1970)

|

| Two laps to go. Mccafferty leads from Stewart, Keino, Clarke, Taylor and Rushmer. |

The field was comprised of three Scots, three Englishmen, two Kenyans, two New Zealanders and one runner each from Australia, Canada, Northern Ireland and Wales. Most prominent were two veterans from the 1964 Olympic final, Ron Clarke and Jipchoge Keino. They both brought a wealth of experience and had both set 5,000 WRs in 1965. Keino, the reigning Olympic 1,500 champion, had already won the 1,500 in these games, decimating the field three days previously. Clarke, who had lowered the 5,000 WR by 18.4 seconds and the 10,000 WR by 39.4 seconds, was running well, but he had been beaten in the 10,000 a week earlier. This race was regarded as his last chance to win a gold medal in a major games.

There were young runners ready to challenge these two giants of middle-distance. England had two fine ones in Allan Rushmer and Dick Taylor. Taylor had the world’s fastest time of the year (13:26.2); Rushmer had represented Great Britain in the Mexico Olympics and had clocked a fast 13:37 in June. The Scottish runners were just as impressive with Ian Stewart, Ian McCafferty and 10,000 winner Lachie Stewart. Ian Stewart was the 5,000 reigning European Champion, while McCafferty had run 13:29.6 in June behind Taylor’s 13:26.2. Finally there were two potential winners in Dick Quax, who had given Keino a great races in the 1,500, and John Ngeno of Kenya, who had finished a good sixth in the 10,000.

Competitor Dick Taylor summed up the prospects of this race: “Everyone will be in there fighting and the possibilities of what could happen are so many it’s frightening. I don’t think I dare pick a winner for certainty. It should be a classic.” (Times, July, 1970)

Tactics

|

| One lap to go. Stewart leads with Keino on his shoulder and McCafferty tucked in behind.Clarke is starting to lose contact. |

Two of the main contenders were expected to push the pace, as they lacked the finishing kick needed to win a slow major race. Dick Taylor clearly decided that a fast race was his best chance. “I want them all shaken up, especially Keino,” Taylor told Neil Allen of The Times. It’s my only chance.” (July 25, 1970) Ron Clarke knew only too well that to win he would have to break away before the last lap. There was talk before the race of Clarke helping Taylor with the pace-making, but no special plans had been made. Ian Stewart saw Keino as the main danger; he planned to keep pushing the Kenyan so that he couldn’t control the race and wouldn’t have any reserves in the last 150m.

Race

After a very slow first lap of 70.8 led in part by a reluctant Rushmer, Taylor had to take the lead. He ran steady 64-second laps, passing 1,000 in 2:47.0 and 2,000 in 5:28.6 (13:41 speed). With two more laps of 63.4 and 63.6, Taylor’s tactic was beginning to work: he had only five with him--Stewart, Clarke, McCafferty, Rushmer and Ngeno.

But now Taylor slowed (64.8, 65.4, 66.2); 4,000 was reached in 10:52 (13:35 speed). It was significant that Clarke did not take over to maintain a fast pace; he was as vulnerable as Taylor in a fast finish. As the pace gradually slowed, the pressure increased for someone to make a move. And it was McCafferty who finally charged into the lead with 870m left. Stewart too had been considering a move: “I remember thinking ‘I’m glad somebody else had gone now rather than me.’” (Jon Wigley, Athletics Weekly) McCafferty’s increased pace left all but Keino and Stewart behind. Clarke was trying to hold on, but it was now really a three-man race: two Scots against a Kenyan.

|

| On the crown of the last bend. McCafferty, lying third, is about to make his move. |

McCafferty led until 550 to go, when Stewart took the lead. “We thought if I could keep Keino under pressure until 150m from the tape, I could possibly get him. And that is why I took off so early to really make him have to run hard rather than to let him decide ‘to go now.’” (Wigley, Athletics Weekly) Gradually accelerating all the time, Stewart passed the bell in 12:27.4, with McCafferty behind him and Keino on McCafferty’s shoulder. Right after the bell Keino moved up to Stewart’s shoulder; he looked in control. But Stewart kept upping the pace. This acceleration showed most on Clarke; he had been within 5m of the leaders at the bell, but he was almost 20m down by the time he entered the back straight.

Racing down the back straight at high speed, the leading trio kept the same positions: Stewart in the lead, Keino slightly wide on Stewart’s shoulder and McCafferty tucked in behind Stewart. At 200 Keino tried to make his move, but Stewart resisted, forcing Keino to tuck in behind him round the bend. McCafferty was still with them, staying close behind Keino, and just past the crown of the bend he made his move. It seemed almost impossible for him to overtake, for the front two were running so fast.

Nevertheless, McCafferty was past Keino by the time they hit the straight. At the same time Stewart began his final effort: “I came out of the bend, put my head down and started to go.” (Wigley, Athletics Weekly) Keino knew he was beaten and looked back to see how safe third place was. Meanwhile, McCafferty’s incredible sprint got him closer and closer to Stewart, despite the latter’s surge. With 50 to go it looked possible that McCafferty could get the gold. But at that point he ran out of steam, and his head started to rock from side to side.

|

| 50m to go. McCafferty tries to catch Stewart. This is the closest he got. Meanwhile, Keino looks back. |

Stewart held his form to the tape for a glorious victory. He had run 13 seconds faster than ever before to clock the third fastest 5,000 time ever. It was a new European record. His last 1,000 took 2:30.8, his last lap was run in 55.4 and his last 200 in 26.4. McCafferty had come so close to him and so close to glory. He too was under the European record and beat his PB by over six seconds. Stewart and McCafferty became the second and third fastest 5,000 runners all-time.

Behind these two Scots, Keino still ran within 3.4 seconds of his PB—despite easing up in the last straight. And Rushmer ran brilliantly to beat Clarke for fourth with a seven-second PB. A tired-looking Clarke disappointed in fifth. As in the 10,000 he ran without the competitive flair expected in a major games. The early pacemaker Dick Taylor, with two spike injuries from his two previous Commonwealth races and maybe a little tired from his bronze-medal run in the 10,000, rounded off the first six.

1. Ian Stewart SCO 13:22.8; 2. Ian McCafferty SCO 13: 23.4; 3. Kip Keino KEN 13:27.6; 4. Allan Rushmer ENG 13:29.8; 5. Ron Clarke AUS 13:32.4; 6. Dick Taylor ENG 13:33.8.

10,000

A huge field of 29 runners lined up at the start. A lot of interest was focused on Ron Clarke (33). This was his fifth major games, and he still had not won a gold medal. The great Australian runner was nearing the end of his career, so this was likely to be his last chance. He had not shown great form in 1970, his best 10,000 time being 28:43.8. Although Clarke was the sentimental choice a lot of the spectators, the Scottish interest was in Lachie Stewart, who came into the race with a 28:33.4 PB. Another notable entrant was Naftali Temu, the Olympic champion, but he was hampered by a foot injury. English hopes rested mainly on Dick Taylor, who had run the fastest 5,000 so far in 1970 (13:29.0), as well as the second-fastest 10,000 (28:06.6) the previous year.

|

| Stewart waits patiently in third asTaylor and Clarke share the lead. |

Despite the windy conditions, Canadian Jerome Drayton did a lot of the early leading. 5,000 was reached in a respectable 14:09.2. It was only in the 18th lap that the race got serious. Clarke made a break and gradually reduced the leading group to three as only Taylor (25) and Stewart (27) were able to stay with him. With two laps to go, a relaxed Clarke moved out and let a tired-looking Taylor run inside him. For the next 600, round three bends, Clarke inexplicably ran beside and outside Taylor, almost in the second lane. On the back straight of the penultimate lap they were running in time—same cadence, same stride length. Stewart meanwhile, looking comfortable, stayed tucked in behind the two leaders and sheltered from any headwind.

|

| The smile of victory. Lachie Stewart finshes clear of Clarke and Taylor. |

With 230m to go, Clarke finally took the lead, but his move was easy for Stewart to match. While Taylor dropped back round the last bend, Stewart waited patiently close behind the Australian. His decisive effort came as he entered the straight; Clarke had no answer. The Meadowbank crowd had a new Scottish hero, but there was some sadness over Clarke’s defeat. “I’m sorry I had to beat Clarke,” Lachie Stewart said. (Athletics Weekly, Aug. 1, 1970)

Due to Clarke’s surge from lap 18, the second 5,000 split was faster: 14:02.6 to 14: 08.2. The first three finishers ran the fastest 1970 times after Bedford’s leading 28:06.2.

1. Lachie Stewart SCO 28:11.8; 2. Ron Clarke AUS 28:13.4; 3. Dick Taylor ENG 28:15.4; 4. Roger Matthews ENG 28:21.4; 5. John Caine ENG 28:27.6; 6. John Ngeno KEN 28:31.4.

Marathon

The field for this race was truly stellar. The reigning Commonwealth Marathon champion, Jim Alder of Scotland, was back, this time running in front of his home crowd. But the world’s fastest-ever marathoner, Derek Clayton of Australia, was regarded by most as the favorite this time. His 2:08:33.6 World Best, run in Rotterdam the previous year, had shocked the running fraternity. Clayton also had a 2:09:36.4 from the Fukuoka Marathon to show his World Best was not a freak run. Another Fukuoka winner, Canadian Jerome Drayton was also in the field. He had won that race the previous December in 2:11:13. And second in that race was another Commonwealth competitor, Ron Hill, who was the reigning European champion. Then there was a second top-class Englishman, Bill Adcocks, who had run a fast 2:11:07 in Athens in April.

|

| Drayton is the early leader. Clayton issecond, and Hill, the winner, fifth. |

Thirty-two runners were at the start line; twenty-four were to finish. Clayton clearly thought his best chance was in a fast race. He led for the first five miles (a very fast 23:45), but then dropped back, leaving three runners in the lead: Ron Hill, Ndoo of Kenya and Singh of India. Soon Hill pushed ahead, but then waited for Ndoo and Clayton at the top of a hill. A couple of miles later he went ahead again, passing the 10-mile mark in an astonishing 47:45—close to 2:05 speed. Nevertheless, at the halfway turnaround he could see that his lead over Drayton, Alder and Trevor Wright was not great. Hill passed 15 miles in 72:18—eight seconds a mile slower than his speed at 10 miles. He slowed a little more to pass 20 miles 1:20 ahead in 1:37:30. Behind him, Alder passed Drayton just before the 20-mile mark, as did Don Faircloth (21) of England.

Alder was tiring at this point, and he was running to hold on to his second place. Meanwhile Hill extended his lead over the last six miles and finished first with a 2:46 margin in the very fast time of 2:09:28. Alder’s margin over Faircloth was 15 seconds. Fourth was Kiwi Jack Foster (38). Adcocks in sixth was handicapped by a bad back and might well have been in the medals had he been 100%. Both Clayton and Drayton dropped out of the race.

1. Ron Hill ENG 2:09:28; 2. Jim Alder SCO 2:12:04; 3. Don Faircloth ENG 2:12:19; 4. Jack Foster NZL 2:14:44; 5. John Stephen TAN 2:15:05; 6. Bill Adcocks ENG 2:15:10.

Leave a Comment