Gunder Hagg’s Training

(Much of the material for this article comes from Gunder Hägg's Dagbok, which was published in Stockholm by Tidens Förlag in 1952. I have also used an article, "Kanske Bättre Kondition än Någon Nånsin" written by Hagg for a handbook entitled Vålådalen published in 1953 by Åhlén and Åkerlunds Förlags AB.)

Over a period of five years in the 1940s, while most of the world was at war, Gunder Hägg was rewriting the middle-distance record book in neutral Sweden. Many of these records were set in competition with his great rival Arne Andersson, and there is no doubt that this competition pushed Hägg to faster times. He was a great competitor who always came through in the big races. But fierce competition doesn’t fully explain his remarkable success on the cinder track. Also crucial were his early childhood conditioning and his innovative training methods.

Childhood Conditioning

The son of a forester in rural Jämtland, Hägg grew up working in the forests with his father. So like many champion runners—Basil Heatley and Bob Schul grew up on farms—he carried out heavy physical work from an early age. He also had to travel long distances on foot to and from the forest areas where his father worked. Much of this travel was done by running in the summer and skiing in the winter. This combination of logging and travel meant that the young Hägg soon became known for his physical strength and stamina.

First Serious Training

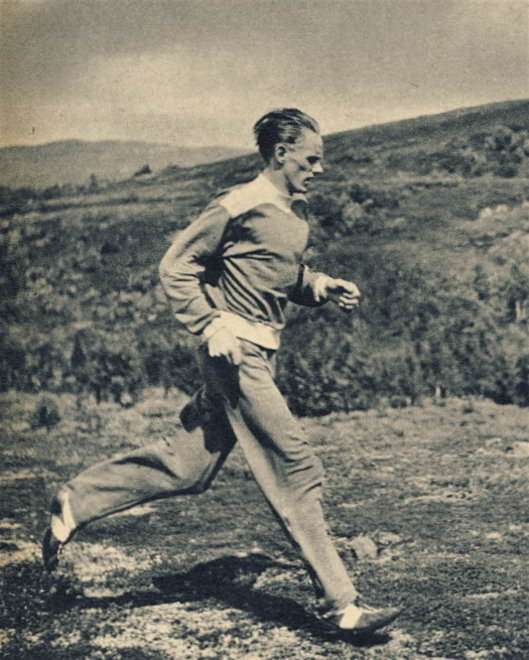

|

| Out in the hills. Note his flimsy shoes.Are they spikes? |

In his mid-teens his love of physical work found expression in running. By coincidence one of Sweden’s finest runners, Henry Kälarne, also lived in the remote Jämtland area, and he naturally became Hägg’s role model. After some early wins locally, Hägg was fortunate to attract the attention of Kälarne’s coach, Friedof Westman. This Jämtland farmer offered Hägg a job and the bedroom that Kälarne had once used. Thus began the first stage of Hägg’s training.

In the first year, before serious training began, Hägg ran 15:00.7 for 5,000 and 4:07.6 for 1,500—good times for a 19-year-old. Westman was a careful and patient coach. Taking into account that his new athlete was working physically on the farm all day, he didn’t let him train too hard for the first year. As Hägg has written, “In the winter of 1939 I turned 20, and according to Friedof Westman it was the right time to progress to a more serious and rational training. Before that the wise “sport-lover” had not pushed me into a set schedule. He was afraid that I would break myself and grow tired.’ (Dagbok, p.12)

Hägg provides minimal details of the schedule that Westman devised for the winter of 1938-1939. He was set five sessions a week: two one-hour runs, two 10K road walks, and one long hike of 30-50K. Clearly Westman was aiming to work solely on Hägg’s strength and stamina. However, this first winter’s training all came to nought as Hägg got sick early in the summer of 1939 and didn’t race at all.

Radical Changes

Missing a whole summer of competition made Hägg all the more determined. And when in December 1939 he was posted with the Swedish military to Norbotten in the far north, he devised a very different form of training. Rather than the long runs and hikes that he had done with Westman, Hägg embarked on a schedule of intense and short sessions interspersed with days of cross-country skiing that were often part of his military duties. His running sessions were almost always 5K.

It is not clear what the source of this new regimen was. Despite his association with Westman, Hägg always said that he never had a coach, but he must have learned about training from others. Apart from Westman, Hägg had been in contact with the father of Fartlek, Gösta Holmer. He had spent time with his role-model Kälarne. It also seems probable that by this time he also knew the local coach and resort-owner Gösta Olander. What Hägg did in Norbotten was to adapt his training to the winter conditions of northern Sweden, where the snow was often knee- or hip-deep, and where the cold was intense. Some days it was too cold to train, but he always had to train in very cold temperatures and this was one important reason for his short running sessions: “I kept warm by running fast.” (Dagbok, p.16) He was able to train longer when cross-country skiing because that activity involved the whole body in heavy work and thus kept him warm.

So Hägg found a hilly forest coursein Norbotten that was near a cleared road and began regular sessions of 2,500m of snow-running (resistance work) and 2,500m of road-running (tempo work). He didn’t use the road part for long in the first year—maybe because the roads weren’t often cleared of snow. This combination of snow and road, however, became his staple winter session for the following two years. Note that in his logs, Hägg never mentions warm-up or warm-down, but I suspect these were often done indoors during the very cold weather.

Norbotten 1939-1940

Note: All lists of Hägg’s schedules have been condensed to avoid repetition. The workouts have been organized in sections to show fundamental changes in his workouts (i.e. when snow is no longer on the ground).

This winter’s training was carried out in the far north, where there was more snow and thus probably more difficulty finding clear roads. Thus his snow-road combination was done only in the early winter. When the snow became deep, Hägg was forced to do more snow-running and cross-country skiing. For example, in the 48 days from 25-2 to 13-4 he ran only eight times on the road. For the “hard runs” from 15-4, Hägg does not specify the terrain.

18-12 to 27-12 (11 days) 2,500 Snow-running/2,500 running (7 days) 12K CC Skiing (two days) Military march (7K: one day) Rest (one day)28-12 to 12-2 (46 days) Skiing (15-30K: 9 days) 2,500 snow-running/2,500 running (6 days) Running in deep snow 4,000 (5 days) Hard 5,000 run (4 days) Military march (12-15K: two days) Deep-snow running (5K: two days) Sleigh pulling and running (8K: one day) Hard skiing (5K: one day) Rest (5 days) Too cold to train (11 days)13-2 to 23-2 (11 days) Complete rest 25-2 to 13-4 (48 days) Hard 5K in deep snow (20 days) CC skiing (15-40K) (11 days--often military) Road runs (2-10K) (5 days) Road runs (2-7K: 3 days) Rest (5 days) Too cold to train (3 days) Military march (10K: one day)15-4 to 16-5 (32 days) Hard 5K runs (16 days) Easy 3K or 5K runs (7 days) One hour’s light exercise—second session of day (7 days) Hard 7-8K runs (two days) Hard Fartlek (5k: one day) Military march (17K: one day) Rest (5 days)17-5 to 21-5 Travel and rest22-5 to 15-6 (25 days) am: Hard 5K; pm: fartlek 4K (5 days) am: Light 5K; pm: fartlek 4K (4 days) Hard 5K runs (2 days) Light runs (3-5K: 7 days) Competition (2) 5:23.2/3:59.6 PB Time-trial 1,600 Rest (4 days)The combination of intense running and long cross-country skiing soon bore fruit in the 1940 track season. He started the season positively: “Before the summer season of 1940, I was extremely confident in my training program. I believed I could set WRs if I didn’t get sick.” (24) After breaking 4:00 for 1,500 for the first time in mid-June, Hägg ran 3:51.8 on June 30th, beating Kälarne and Jansson, two of the best Swedish runners. And although Kälarne got his revenge in the August Swedish Championships by 0.1 of a second, Hägg improved to 3:48.8, which was just one second off Lovelock’s WR. Clearly the regimen that Hägg had developed was working well, propelling him from a promising local runner to a world-class one. “The season in Norbotten had strengthened my view that only hard, intensive and purposeful training will give good results,” he wrote. (24)

Vålådalen 1940-1

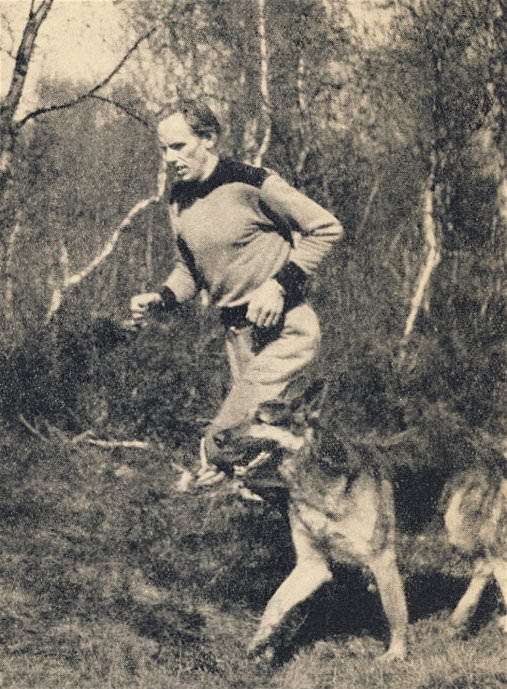

|

| Hägg (in foreground) runs in deep snow at Vålådalen. |

During the summer of 1940, Hägg was approached by local Jämtland resort owner and coach, Gösta Olander. Olander encouraged athletes of all sports to stay at his resort, where there were excellent facilities. Hägg recalls, “After the winter in Norbotten and my first track season as a trained runner when I had seen possibilities, I decided with pleasure to accept Gösta Olander’s offer to move to Vålådalen and to work as a handyman the following winter.” (24)

Hägg arrived at Vålådalen on December 8, 1940, and went straight into serious training. The day before he arrived, he wrote in his diary, “I intend to train the same way as I did last year. I believe that the hard training is the best.” (26) His belief in intensive training is repeated in another diary entry: “One must learn “no pain—no gain,” as Gosse Holmer correctly pointed out many times. And one must push so hard during training that one gets thoroughly tired out.” (27)

|

| Hägg runs ahead of Maja, the resident Vålådalen crane. |

So he devised another 5K course similar to the one he had used in Norbotten: “I tried to find a suitable course in the birch forests and swamps. The one I chose had undulations and ended up with a steep hill that fed on to the Undersacker road 2K from Vålådalen. These last 2K would be a stretch where I could run at full speed regardless of snowfall. This course had everything a runner could ask for…. Many times I was dead tired on reaching the cleared road, but I was never so tired that I couldn’t move into top speed.” (“Possibly Better Condition Than Anyone Anytime,” Vålådalen, ed. Gunvald Håkonson, p.56) Thus he began the sessions he had first used at the start of the previous winter in Norbotten: 3,000m of deep-snow running followed by 2,000m of road running. The table below shows that he used this session, and one variant, 84 days over the winter. As in Norbotten, he also included a fair number of cross-country skiing days. He stuck to his six-days-a-week schedule for over four months.

8-12 to 22-12 (15 days) 2,500 deep-snow running/2,500 road (10 days) 5K hard road run (one day) Rest (4 days)23-12 to 4-2 (43 days) 3,000 deep snow-running/2,000 road (25 days) Cross-country skiing 8-10K (3 days) Rest (5 days) 2-day breaks (4 times)5-2 to 21-2 (17 days) Fast cross-country skiing (6-10K: 5 days) 3,000 deep-snow running/2,000 road (5 days) Steady cross-country skiing (10-17K: 4 days) Hard run in deep snow (12K: one day) Road run/road walk (6K/8K: one day) Sick (one day)22-2 to 25-2 Travel to Ostersund and back 25-2 to 15-3 (19 days) 2,500 deep- snow running/2,500 road (13 days) Rest (6 days)16-3 to 29-3 (14 days) 3,000 deep-snow running/2,000 road (12 days) Rest (two days)30-3 to 20-4 (22 days) 3,000 deep-snow running/2,000 road (19 days) Rest (3 days)21-4 to 28-4 (8 days) 6,000 road runs: 5 hard/2 steadyHägg described how he felt after his time in Vålådalen: “I was in good form and was considerably stronger than at the same time last year. I had a very good time in Vålådalen, where I had done odd jobs like cutting firewood, setting fires, etc., which were part of any handyman’s duties. I still had a fair amount of time left over—the training didn’t take more than half an hour a day.” (31)

But Vålådalen had provided more than a training venue: “I was in better shape perhaps than anyone had been before. Some of it had to do with the trails around Vålådalen, but most of it had to do with Gösta [Olander], who created a positive and comfortable atmosphere. And when everything is counted, that atmosphere is more important for an athlete in training.” (Vålådalen, p.56) Clearly his interaction with Olander, although not technically an athlete-coach interaction, was most beneficial. It is noteworthy that before all his great races, Hägg spent time with Olander at Vålådalen.

Gävle 1941-1942

Hägg left Vålådalen in the spring of 1941 to take a job as a fireman in Gävle. His new job allowed him to compete regularly in June, July and August. He was unbeaten in 17 races and set his first world record with a time of 3:47.6, just 0.2 under Lovelock‘s 1936 record. After the competition season he worked full-time and “didn’t take one step of training until December.” (36) At this time he planned to run for only 20 minutes a day: “I plan to use my meal break from 16:30 to 17:30 for training. There won’t be much time as I also have to eat. I can run on the horse-racing track near the fire station. It should be enough to do this six times a week, 20 minutes a run. It will be harder running than any previous year. Probably there won’t be much snow.” (37)

Hägg settled into his new training regime on December 7, 1941. With less snow on the coast, he had to modify his training. It is notable that he included fartlek regularly from the middle of April. Another difference was the absence of cross-country skiing, except when he visited Vålådalen. He managed an 18-day visit to Olander’s touriststation over the Christmas holiday. Also noteworthy is that he switched for the first time to twice-a-day training, as he geared up for the start of competition in July.

7-12 to 13-12 (7 days) 4K cross-country/2K road (5 days) 6K road run (one day) Rest (one day)14-12 to 31-12 (17 days) 4K deep-snow running/2K road (12 days)(Vålådalen) 5K road run (2 days) 5K cross-country skiing (one day) Rest (3 days)1-1 to 6-2 (37 days) 4K cross-country/2K road (6 days a week)7-2 to 15-2 (9 days) Easy Cross-country skiing (8 days)(Vålådalen) 4K deep-snow running/2K road (one day)16-2 to 20-2 (5 days) CC skiing minimum 20K (daily)24-2 to 20-3 (25 days) 3,000 deep snow/2,000 road (12 days) 5K road run (4 days hard/one steady) Cross-country skiing (3 days) 3K skating (one day) Rest (3 days)14-4 to 12-5 (29 days) 3,000 deep snow/2,000 road (one day) Fartlek in forest (11 times) Hard forest runs (5 times) 3-5K Easy forest runs (4 times) 5-8K Rest (8 days)13-5 to 31-5 (19 days) Fast runs (3-6K: 4 days) Fartlek (6-9K:10 times) Easy run (10K: one day) Rest (4 days)1-6 to 30-6 (31 days) Switch to twice-a-day training:(Vålådalen 15-6 to 28-6) am: Light runs (3-10K:14 days). Rest (7 times) Hard runs (3-6K: 4 days) near end of month. pm: Fast forest runs (3-6K: 16 days) Fast track runs (4 days: 2 timed: 2:28.5/3:50.6)After finishing his final two weeks of preparation in Vålådalen, Hägg went on to set a WR in his first race with a 4:06.2 Mile. During his 1942 season he set ten WRs from 1,500 to 5,000. With his solid training background he was able to maintain top form for three months, racing 34 times. Clearly his pattern of training was ideal, but the next year he broke that pattern.

Gävle 1942-1943

After resting in the fall, Hägg was back training in December 1942: “My desire was as strong as three years before. In fact it had increased. When I was in Norbotten I calculated I would peak in 1943 or 1944. My motivation was the highest.” (49) Hägg wrote that he continued with the same training as the previous year, but he doesn’t give any details until March 15, 1943. Still, it is clear that he carried out more than three months’ solid training. However, in March Hägg decided to break his annual routine of training and racing. He agreed to cross the Atlantic to compete in the 1943 American outdoor season. Thus the following training was done with this trip in mind.

15-3 to 28-3 (14 days) Hard road runs (7K: 9 days) Hard road fartlek (7K: 2 days) Easy road run (one day) Flat-out 5K road run (one day) Rest (one day)29-3 to 15-4 (18 days) am: Light road running (11 days) Rest (7 days) pm: Road fartlek (3-7K:13 days) Rest (5 days)16-4 to 5-5 (20 days) am: Light road running (12 days) 5K Hard road running (3 days) Rest (5 days) pm: Fartlek (6 days) Hard fartlek (4 days) Rest (10 days)Unable to obtain a plane seat, Hägg finally made the journey across the Atlantic by steamer. The four-week trip meant he was unable to train, except for a little jogging along a 70m corridor. Still he had a successful competitive summer season in the USA, although his times were never more than respectable. And he maintained his unbeaten record for the third summer in a row.

By the time he had made the dangerous trip home, the Swedish track season was over. So he rested until the new year. A big change in his life occurred early in January when he moved from Gävle to Malmö. The Malmö club had arranged a job for him, so he gave up his fireman’s job and began work in a clothes shop. This move meant that his winter training needed changes: Malmö had little snow. So he describes his cross-country terrain for training in Malmö as barmark (bare ground).

Malmö 1944

1-1 to 18-1 (19 days) Only 8 days of training 3-5K snow and road runningMove to Malmö25-1 to 24-2 (31 days) Hard cross-country runs (3K: 4 days) Light cross-country runs (3-4K: 6 days) Fartlek (2K: 2 days) Rest (9 days)25-2 to 15-3 (20 days) Hard cross-country fartlek (4-5K: 10 days). Steady cross-country runs (4-5K: 4 days) Rest (6 days)Hägg provides no more detail of his spring training, but he does record a two week visit to Vålådalen in June: “there I trained extremely hard for two weeks on the old, familiar trails. The program was the same as in 1942.” (62) A stay with Olander was just what he needed to face a challenging competitive season. While Hägg was abroad in the USA, Arne Andersson had broken both his 1,500 and Mile WRs and was clearly a bigger threat than before.

But the preparation that Olander and Hägg did in 1942 worked again. As in 1942, Hägg broke a WR in his first race after leaving Vålådalen and broke two more in the next six weeks. Nevertheless, he was no longer able to beat Andersson as he had before; in fact, over the summer he lost to his rival six times and beat him only once (with a brilliant 3:43.0 WR). This was the first season since 1941 that he had not won every race. Clearly, though he had improved, Hägg was affected by the rigours of his American trip, which not only disrupted his 1943 spring training but also left him drained physically and mentally. It is noteworthy that as well as losing regularly to Andersson, his times quickly deteriorated late in the 1944 season. Where in the past he could maintain peak form for three months, his peak in 1944 lasted only a month and a half.

Malmö 1944-1945

Hägg’s last competitive season (1945) was also affected by a trip to the USA. This time he chose the indoor season, again making the transatlantic trip by boat. Accustomed to taking a break in the fall, Hägg had to undergo a crash training program to prepare for competition at the start of March. He started training on November 25, running his regular 5K over the country, alternating hard and easy days. In the middle of December he was able to get away for a week to Vålådalen for some deep-snow running. He managed to do four sessions of his snow-road combination. But the upcoming dangerous war-time trip was on his mind. He wrote that he was “affected by uncertainty—not training as usual.” (64)

His second American tour of five indoor races negatively affected his 1945 outdoor season. He was away for almost four months and spent some time in New York waiting for a passage home and worrying about a lawsuit threatened by his Malmö employer. His condition when he got home on May 22 could not have been good. To get ready for the imminent season, he began twice-a-day training in Malmö the next day.

23-5 to 1-6 (10 days) am: Hard running (4k: 9 days) Rest (one day) pm: Hard running (4K: 4 days) Fartlek (4-5K: 3 days) Hard Fartlek (4-5K: 3 days)Two days later his competitive season began. In five low-key races in June he managed to lower his 1,500 time from 3:58.2 to 3:51.4. Then he went up to Vålådalen for two weeks. It is hard not to use the word “magic” when considering how Olander and Vålådalen affected Hägg’s performances. For after two weeks there, Hägg went back to Malmö and ran his most extraordinary race. Although not in the condition he would have wanted, he nevertheless ran a brilliant 4:01.3 to defeat Andersson and reclaim his Mile WR. After this race, his times for the rest of his last season were mediocre. In six races over 1,500 he didn’t get below 3:50, and in a late-season Mile he was fourth in 4:13.2, over eight seconds behind the winner Strand. His last season was a big anti-climax—except for that one great Mile race. Then a subsequent lifetime ban from competition for professionalism denied the 26-year-old the chance to see if he could bounce back in 1946.

Evaluation

Hägg’s strong streak of independence meant that he always trained alone and never put himself under the charge of one coach. Still, he was under Friedof Westman’s influence for a considerable period in his teens, and later he developed a close relationship with Gösta Olander, whom he once called his second father. Thus the matter of the origin of Hägg’s basic winter session from 1939 on (a combination of deep-snow running and tempo road running) must take into consideration his relationship with these two coaches and well as with Kälarne.

|

| Training at Vålådalen with Larson. |

The matter is complicated in that it is not clear how well Hägg knew Olander before his initial 1939-1940 stay at Vålådalen. However, his regular winter session of snow running followed by road running has all the marks of Olander’s training approach, which combined resistance and speed. Most coaches would have organized resistance and tempo training in different sessions. The unique quality of the session Hägg employed was that he did the tempo running after his resistance, thus running fast when there was already fatigue and lactic acid in his system. This same principle was evident in Olander’s summer sessions on his 220m path where a gradual downhill for 150m (enabling runners to reach a high tempo) was followed by a gradually steeper climb that required the runner to maintain tempo with increasing resistance. Olander appreciated that a runner needed the ability to cope with fatigue and lactic acid while tempo running. Hence I suspect that Olander influenced the creation of Hägg’s unique resistance/tempo session.

Olander’s influence can also be seen in Hägg’s choice of training venue. He hardly ever visited a track except for competition, and preferred a natural rough terrain wherever possible. In fact Hägg’s track was the compacted grit road common in rural areas of Sweden. His snow-road combination sessions were generally done in racing spikes.

From today’s perspective, another noteworthy aspect is the short duration of Hägg’s training sessions. He rarely trained for more that 30 minutes, not counting any warm-up or warm-down. Indeed, while at Gävle, he spent only 20 minutes for his sessions. But one has to balance that with his often long cross-country skiing outings that must have done a lot for his endurance. It is also important to remember that Hägg was primarily a 1,500 runner. He only dabbled in longer races, though with great success.

Another noticeable aspect of Hägg’s training is his consistency. He missed sessions only if he had a planned rest day or if the winter conditions were too harsh. Hägg’s character is clearly important here. In his diary he admits to sometimes having negative thoughts during his training, but he says he had an ability to refocus his mind on positive things. Injuries could have spoiled his consistency, but they were never a problem. Of course, there is an element of good fortune in this, but his use of natural locations and his short running sessions must also be taken into account to explain the absence of injuries.

Hägg was only able to carry out a solid and full winter’s training three times as an adult. Each of these consecutive winters saw him improve. But then his two USA tours came into the picture and adversely affected his last 1943, 1944 and 1945 seasons by preventing him from carrying out a solid and consistent winter’s training. Without this solid winter conditioning Hägg was no longer a dominant force in the 1944 and 1945 seasons. But his three solid winters of training improved his 1,500 time from 4:04.6 to 3:45.8 and brought him eleven WRs before he made his USA tours. It’s surprising that his unusual training methods have never become firmly established in northern countries.

I am most grateful to Ingemar Karlsson for his help in translating some of Hägg’s diary (Dagbok). After he had generously agreed to help me, I discovered that Ingemar once saw Hägg compete at Falköping on July 30, 1945.

6 Comments