Articles / Great Races

Keino v. Tummler v Ryun v Norpoth v Whetton (1968)

By John Cobley

20th February 2012

Keino v Ryun v Tummler v Norpoth v Whetton

1,500 Olympic Final

October 20, 1968, Mexico City

Great Races # 21

Pre-Race

This Olympic final saw a confrontation between the two fastest milers ever. And both had question marks against their current form. WR-holder Jim Ryun of the USA had recently battled with two injuries and mono. He had returned to form in the nick of time, qualifying comfortably with a 1,500 time of 3:49.0 (1:50.8 last 800). Kenyan Kip Keino had been suffering from stomach pains (later diagnosed as gall-bladder inflammation) while racing in Europe. And in the 10,000 final that preceded this race he had collapsed from the pain. Still, he was on the start line—against his doctor’s orders. Another question mark against Keino was that he had already run two finals (5,000 and 10,000) as well as three prelims. This race would be a hard test of his ability to recover.

|

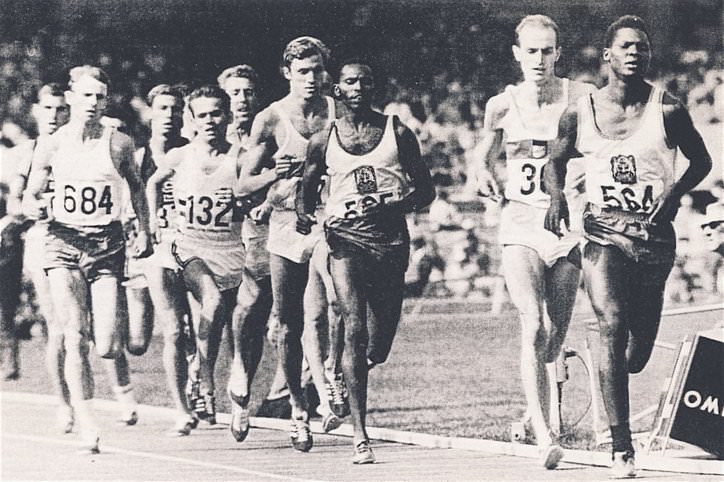

| At 300, Jipcho leads Norpoth, Keino,and Tummler. Ryun is last. |

Of course, the big issue was the 2,240m altitude of Mexico City. Of the 12 finalists, only Keino and his schoolboy team-mate Ben Jipcho lived at altitude. Some of the three Americans and seven Europeans had done some altitude training, but none of them was nearly as acclimatized as the two Kenyans. With this in mind, Keino understood that to beat Ryun he would need to make the pace fast, thereby nullifying the American’s kick: “I prepared myself to have a big lead going into the final quarter,” (Cordner Nelson, Roberto Quercetani, The Milers, p.342). His team-mate Jipcho was told by his team managers to set a fast pace for Keino: “‘This is Keino’s Olympics,’ they told me. ‘You must help him. You’ll have your day another time.’” (Jim Ryun, In Quest of Gold, p.178)

Ryun, on the other hand, knew that if he started fast, he would soon be in oxygen debt. “How I prayed for a slow pace!” he wrote later (Gold, p.92). He needed to run a steady pace so that he could use his kick in the last lap. Still, Ryun could take encouragement from the fact that no one had beaten him over a Mile or 1,500 in three years.

While Ryun and Keino were in a class of their own, several other runners had prospects of a medal. European champion Bodo Tummler of West Germany and André de Hertoghe of Belgium had posted fast times of 3:36.5 and 3:37.1 in a July race in Cologne. Based on their competitive records, Harald Norpoth of West Germany and John Whetton of Britain were also expected to perform well, but their 1,500 times were not as impressive. Notable absentees were Jean Wadoux of France, who had opted for the 5,000, and Jurgen May, who had recently defected from East Germany.

The Race

The race started dramatically when Jipcho roared into the lead, closely followed by Norpoth. His pace was exceptionally fast. Ryun started slowly and ran last, close to the curb. Jipcho took the field through the first lap in a fast 56.0, leading Norpoth and Keino. Keino himself was timed in 56.6 while a cautious Ryun stayed at the back of the field and clocked 58.5.

|

| Keino leads at the bell from Tummler, Norpoth,Whetton and Ryun. |

The positions stayed the same for the next 100. Then Ryun began to move past his two team-mates. At about 670 Keino moved into the lead as the field had two laps to go. With Jipcho dropping back, Keino passed 800 in 1:55.3. Tummler, Norpoth and Whetton (who had moved up from the pack between 600 and 800) were 4-8m back. Ryun, having made up four places running wide round the bend, was now dangerously adrift in sixth (1:58.5)

On the third lap, Ryun passed Jipcho just before the bend, but he was well down on the four ahead of him. At the front, Keino worked hard to increase his lead over Tummler, Norpoth and Whetton. At the bell he was 7m clear. Could he possibly maintain this breakneck speed for another 400? Ryun meanwhile, with a clear track in front of him, started to claw back a few precious yards, but his task looked impossible unless the four in front of him cracked.

Ryun put in an incredible effort between 1,000 and 1,200, making up a huge amount of ground on Tummler, Norpoth and Whetton: “I saw that the race was in danger of getting away from me and realized that, oxygen or not, I had to do something quick.” (Gold, p.93) While Keino was increasing his lead, Ryun caught Whetton just before 1,200. Keino was timed at 2:53.4 and Ryun, in fourth, 2:56.0. The American had run the third lap in 57.7—compared to Keino’s 58.1.

Now in top gear, Ryun quickly challenged the two Germans on the back straight. Tummler was able to react; Norpoth fell back to fourth. While Keino maintained his lead, Tummler and Ryun now ran shoulder-to-shoulder. The German held the inside round the last bend, forcing Ryun to run at least a couple of extra meters. It was only just before the straight that Ryun was able to move ahead and on to the curb. He had finally gained second place, but the gap to Keino in front of him was far too great; all he could do was hold on for second place. Despite looking back three times, he held a clear lead over Tummler as he followed Keino towards the tape.

|

| Keino hits the tape with Ryun, Tummler,Norpoth and Whetton in his wake. |

The Kenyan’s margin of victory was a huge 2.9 seconds, almost the same as his advantage at 1,200. This clear margin of victory followed the pattern set in the previous two Olympic 1,500s, where Elliott and Snell had victory margins of 2.8 and 1.9 seconds. Keino had made his move early, with 800 to go; Elliott went almost as early, with just under 700 to go; Snell went with 300 to go.

Keino’s was a courageous run; there were many who thought that he was sure to crack, so fast was his pace at altitude. As Nelson and Quercetani wrote, “He knew that there was only one way to beat Ryun. He had to take every possible advantage of his body’s uncommon ability to use oxygen, developed from a lifetime of activity at high altitude.” (Milers, p.339) In beating Ryun for the first time, he ran a PB and the second fastest clocking all-time. His exceptional time has led some experts to wonder whether the 2,240m altitude was any handicap at all for the Kenyan over 1,500.

In second place, Ryun ran just as brilliantly. French expert Robert Parienté calculated that the altitude gave Keino a 3-4 second advantage in this race. (La fabuleuse histoire de l’athletisme, p.374) It is generally agreed that Ryun was right not to go with the initial pace. But it is tempting to surmise what might have happened if he had followed the example of Norpoth and stayed right on the heels of the leader from the start. Norpoth, a 1,500/5,000 runner, was not close to Ryun’s ability over 1,500 and yet he hung on for fourth place, admittedly 7.6 seconds behind the leader. Of course, had Ryun stayed close to Keino, he would not have had to run so fast over the last 600. Clearly Norpoth did not develop an early oxygen debt, so why would Ryun have done so? Furthermore, if Ryun had been on Keino’s heels over the last half of the race, he would have had a huge psychological advantage.

Nevertheless, Ryun made an informed decision before the race, and he showed great discipline in sticking to his plan. He ran fairly steadily with laps of 58.5, 60.0, 57.7. His last 300 was run at 55.85 400 speed. Ryun believed the race would be won in 3:39, and he ran well inside that time. He defended his tactics afterwards: “I could not have kept up with [Keino] and still have [had] any kick left for the finish.” (Milers, p.341)

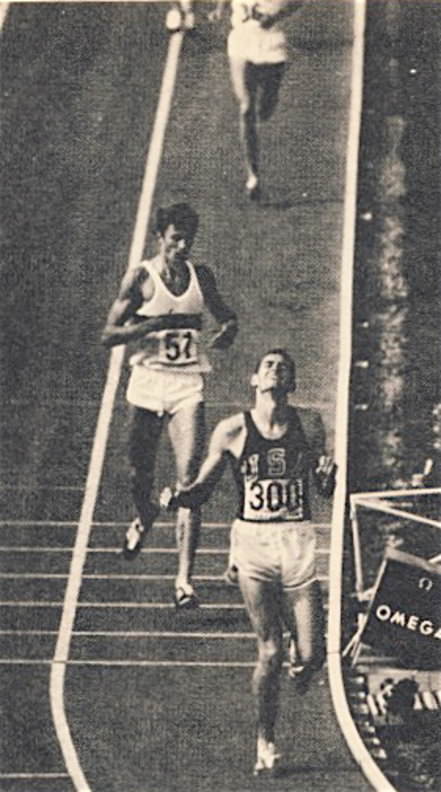

|

| Jim Ryun finishes second, well clear of Tummler. |

Behind the first two, there were some fine performances. Tummler showed why he was Europe’s best 800/1,500 runner. He ran bravely in view of the altitude, and he showed great strength on the last lap, almost holding off Ryun. He had the distinction of being the only European to win a medal in the longer track events. Full credit must also go to his countryman Norpoth, who finished a creditable fourth, 3.5 seconds behind Tummler. Norpoth had surprised many in Tokyo when he finished second in the 5,000. For this race he was under pressure as he had dropped out of the 5,000 on the eighth lap. He put himself on the line in this race, showing determination to stay with the leader as long as possible.

John Whetton of Britain came with a reputation as a good racer, but he was not expected to be up in the top six for this altitude race. He took a big risk after 600 and moved away from the pack to join the three leaders. This risk enabled him to race for the top six, and he must have been thrilled with his fifth position ahead of several top Europeans. “Whetton ran with more courage than I have seen from him before,” wrote veteran British reporter Neil Allen. (Times, October 21, 1968)

Postscript: Several years later Jipcho apologised to Ryun for his pacemaking. He felt that pacemaking was “simply not right in the Olympic Games.” Jipcho told Ryun: “I was pressured into it.” (Gold, p.178)

1. Kipchoge Keino KEN 3:34.9; 2. Jim Ryun USA 3:37.8; 3. Bodo Tummler WG 3:39.0; 4. Harald Norpoth WG 3:42.5; 5. John Whetton GBR 3:43.8; 6. Jacques Boxberger FRA 3:46.6.

2 Comments