1969 EUROPEAN CHAMPIONSHIPS

ATHENS, SEPTEMBER 16-20

Cold-War politics led to a boycott by the West German team for this major championships. The issue was the eligibility of the fastest 5,000 runner entered: Jurgen May. May had defected from East Germany to West Germany two years and three months previously. East Germany had erased May’s name from all their athletic records; West Germany was anxious to have him in their team for these championships. The IAAF had to rule on May’s eligibility and used the three-year qualification period for any athlete changing countries. As May had not met this three-year residency requirement, he was not allowed to compete. In response, the whole West German team withdrew. Thus the championships lost one of the very best teams. In the running events, this meant that Walter Adams, Bodo Tummler, Harald Norpoth and, of course, Jurgen May were denied a chance to compete. British runners took advantage of this and racked up an impressive tally of three gold, one silver and two bronze medals in the five running events.

800

|

| Dieter Fromm holds offast-finishing Plachy |

The absence of Walter Adams of West Germany meant that the top two East Germans, Dieter Fromm and Manfred Matuschewski had only one real challenger, Jozef Plachy of Czechoslovakia. All three had PBs in the 1:45 range, so tactics were crucial. The talented but relatively inexperienced Plachy had to contend with not two but three East Germans in the final. And it would take a savvy runner to deal with this disadvantage. At the other end of the scale, there could hardly have been a more experienced racer than Matuschewski, who was 10 years older than the 20-year-old Plachy and who had won the last two European 800s in 1962 and 1966.

Erhard Schulze, the third East German took the lead and ensured the pace was on the slow side. He passed the bell in 53.5 while his two team-mates kept the talented young Czech boxed in. This tactic enabled Fromm to get the jump on Plachy along the back straight. The outmaneuvered Plachy fought hard to pull the East German back and made up a lot of ground in the last 25 meters, but he was still 0.3 of a second behind at the tape. The aging Matuschewski was third, half a second behind Plachy, while the third East German, Schulze, was last in 1:55.4.

1. Dieter Fromm EG; 1:45.9; 2. Jozef Plachy CZE 1: 46.2; 3. Manfred Matuschewski EG 1:46.8; 4. Yevgeny Arzanov URS 1:47.1;; 5. Hans Mummenthaler SWI 1:47.2; 6. Andrzej Kupczyk POL 1:47.5.

1,500

This race was hugely affected by the absence of Tummler and Norpoth, who had run third and fourth in the Olympics the previous year. The fifth man in that Olympic 1,500, John Whetton, was in the race, but he wasn’t considered one of the favorites. Italian Franco Arese, Andre de Hertoghe of Belgium and Jean Wadoux of France were the most fancied. But none of these three was in the hunt at the end.

On the back straight of the last lap, it was Frank Murphy of Ireland who led into the last curve. Whetton, who was fourth, then moved up two places: “With 200 to go I managed to nip through on the inside of Arese and de Hertoghe, right behind Murphy.” (Nelson and Quercetani, The Milers, p.349) He followed Murphy into the home straight before making his final effort. Murphy resisted well, but Whetton just managed to pass him for the narrowest of wins. The Englishman, who had raced a lot indoors, showed he had the racing skills to do just enough to win. Whetton was regarded as a surprise winner, but the Villanova-trained Murphy was just as surprising in second, although he had recently beaten Whetton for the British AAA title. The race for third place was just as close with both Szordykowski of Poland and Salve of Belgium clocking the same time.

1. John Whetton GBR 3:39.4; 2. Frank Murphy IRE 3:39.5; 3. Henryk Szordykowski POL 3:39.9; 4. Edgard Salve BEL 3:39.9; 4. Andre de Hertoghe BEL 3:40.9; 6. Jean Wadoux 3:41.7.

5,000

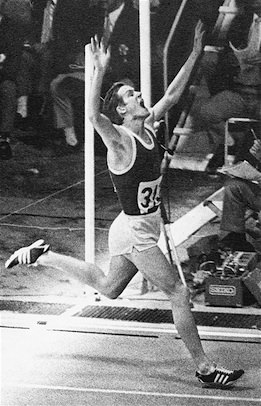

|

| Ian Stewart "toyed with the field." |

With sub-13:30 runners Norpoth and Wadoux absent, the best prospects were Diessner of East Germany, Sharafutdinov of the USSR and 20-year-old Brit Ian Stewart, who had won the European 3,000 indoor title earlier in the year. The pace was slow; the first four laps were all between 67 and 69. This slow pace concerned Stewart, who was aware both of Diessner’s finishing speed and of the dangers of a chaotic mass finish. So the Englishman moved into the lead and upped the pace a little to 66 laps. The 3,000 was reached in 8:21 (13:55 pace).

No one else wanted to lead, despite Stewart’s invitations, so eventually he just stopped. This surprised the field and got the race going. With two laps to go Puttemans made his effort. Here Stewart tells the story: “I went again at 600 meters, but I only half went and at the bell I was leading from Diessner and the Russian [Sharafutdinov], I think. I was still not running flat out, and coming down the back straight the Russian took me; I could see he was sprinting flat out.” (Alastair Aitken, More than Winning, p.136-7) Stewart decided to wait: “I thought, ‘I’ll hit him on the crown of the bend to take him unawares.’ I thought he would not think I would come at him there. I was feeling pretty good then; I was pretty confident I was going to win.” (Aitken, p. 137) And this is exactly what Stewart did, and he reached the tape a full second ahead of Sharafutdinov. According to Neil Allen, Stewart “toyed with the field and destroyed them.” (Times, Sept. 20, 1969) Stewart’s last lap, in which he did not look extended, was 56.3; and his last 1,000 was 2:32.6. Alan Blinston’s excellent third (he ran 13:40 in 1968 and 1969) was another plus for the British team.

1. Ian Stewart GBR 13:44.8; 2. Rashid Sharafutdinov URS 13:45.8; 3. Alan Blinston GBR 13:47.6; 4. Bernd Diessner EG 13:50.4; 5. Dane Korica YUG 13:51.4; 6 . Giuseppe Ardizone ITA 13:51.8 .

10,000

The summer heat of Athens had an impact on this race, as one of the favorites, Dick Taylor of Britain, suffered from heat exhaustion and finished a distant 15th. But it was Jurgen Haase, fresh from a new European record of 28:04.4 in July, who was most fancied. The 24-year-old German was the current European 10,000 champion too, having outsprinted the field after a big battle with Roelants of Belgium. The veteran Roelants was also in the field again.

Not surprisingly the heat influenced the early pace, which was very slow. This was ideal for Haase, who possessed by far the best kick among the finalists. Eventually Roelants realized that he had to up the pace. But his bursts were always matched by Haase, who sprinted away to victory at the bell. His 28:41 time was excellent in the conditions and his 55.8 last lap impressive. Roelants, paying for his attempts to break Haase was eight seconds behind in fifth. The surprise was the second-place finish of British cross-country champion Mike Tagg, who put in a 57 last lap and was the only one to be able to match Haase’s burst at the bell. “In a race like this,” Tagg said, “Haase couldn’t be beaten. It was perfect for him.” (Track & Field News, Sept, 1969)

1. Jurgen Haase EG 28:41.6; 2. Mike Tagg GBR 28:43.2; 3. Nikolai Sviridov URS 28:45.8; 4. Drago Zuntar YUG 28:46.0; 5. Gaston Roelants BEL 28:49.8; 6. Mike Freary 28:49.8.

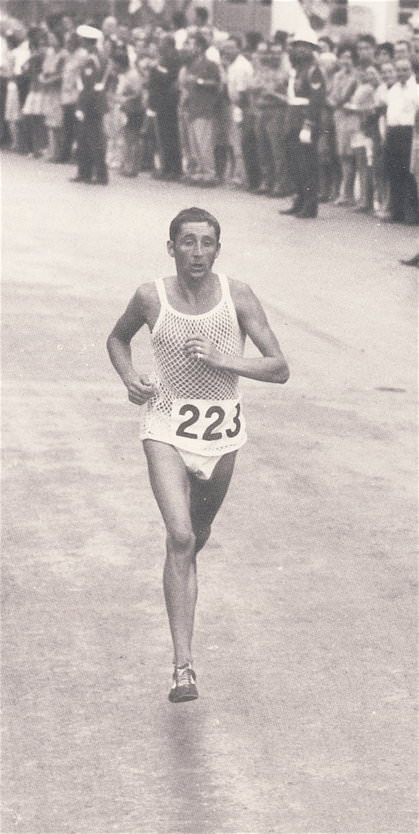

Marathon

|

| Ron Hill was running for second until he saw Roelants up ahead. |

The heat was of course a big factor, though the day of this race was not as hot a anticipated. And to deal with the heat properly required confidence as it was imperative to hold back in the early stages. Nedaljko Farcic of Yugoslavia led from 2 miles. As he opened up a gap, he made an insecure Roelants make the mistake of going after him too early. The Belgian soon had the lead to himself. Ron Hill, on the other hand, had started very conservatively. He gradually moved through the field. Soon after the hilly section started at 12 miles, he caught Farcic. By this time Roelants was well ahead and out of sight, so Hill believed he was now racing for second place.

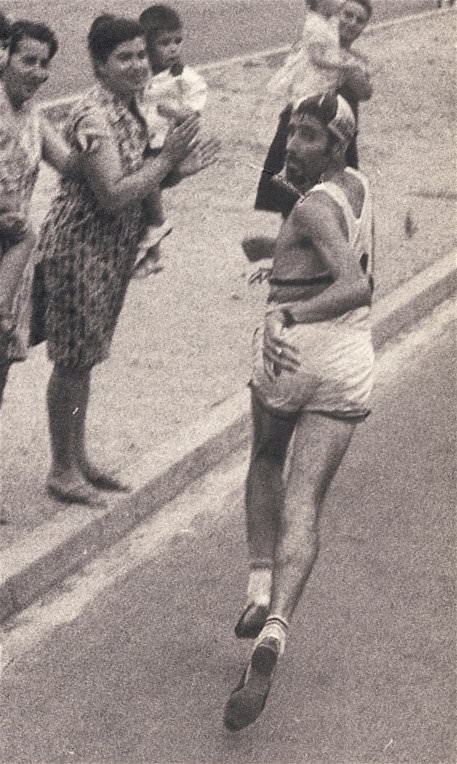

|

| Roelants kept looking back. |

Farcic held on to Hill until 15 Miles (24.4K) before dropping back. Meanwhile, Jim Alder had been moving rapidly through the field. Hi momentum took him past Hill at 17 miles (27.3K). “I had no intention of trying to stay with him,” Hill wrote later. “I was going fast enough to know that I would finish.” (The Long, Hard Road, Part 2, p.52) At 30K Alder was over a minute behind Roelants but held a 30-meter advantage over Hill. Their positions stayed the same for several miles, but at the last uphill section Hill caught the Scot and moved away—with 6 miles (10K) to go. Roelants was having his problems at the front and had begun to worry about his chasers. The Belgian finally came into Hill’s sight with less than 2K to go. Hill, spurred by this unexpected good fortune and the way Roelants kept looking back, went after him. He finally passed Roelants just before the stadium. “I’d done it,” Hill said after, “but we were bloody lucky.” (Times, Sept. 22, 1969) In the last K, after nearly being hit by a Landrover doing a U-turn, Hill moved ahead to a clear 34.4 second victory. In third, a slowing Alder managed to hold off Busch.

1. Ron Hill GBR 2:16:47.8; 2. Gaston Roelants BEL 2:17:22.2; 3. Jim Alder GBR 2:19:05.8; 4. Jurgen Busch EG 2:19:34.8; 5. Ismail Akcay TUR 2:22:16.8; 6. Denes Simon HUN 2:22:58.8.

2 Comments