Ron Hill Profile: Part Two

1938-2021

|

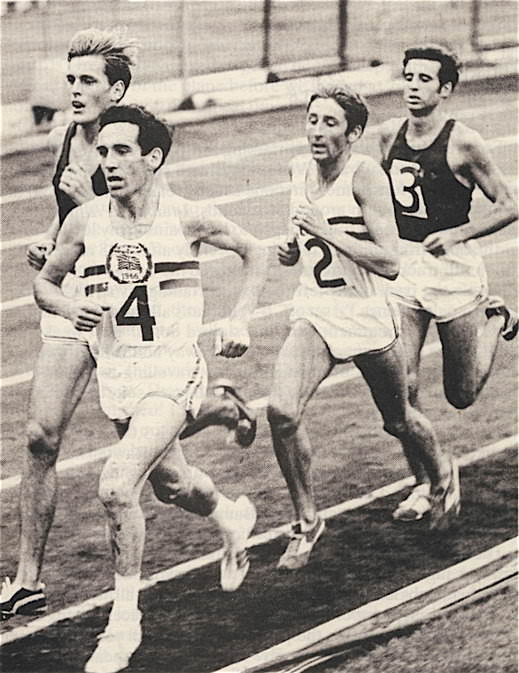

| 1969: Hill (2) wins 10,000 against USA. |

Ron Hill’s seventh place in the 1968 Olympic 10,000 final was his first good performance in a major games. After disappointments in the 1962 Euros, the 1964 Olympics, the 1966 Commonwealth Games and the 1966 Euros, he had finally performed up to his expectations in Mexico. “With such a good run,” he wrote, “I was confident that my training program was right. Long term, I now had the Munich Olympics, and the Marathon there, firmly set in my sights; but, before that, The European Games in Athens (1969) an the Commonwealth Games in Edinburgh (1970) were to be looked forward to.” (1:404) What he wanted most was an Olympic gold medal--“the ultimate symbol of success in running” (2:6)--or if not that, then a European or Commonwealth gold medal.

His training program had been based since 1964 on 13 sessions a week (twice a day except once on Sunday). Gradually he had increased his weekly mileage to 120 in 1968. Initially, this remorseless program caused Hill to break down with injuries or illness. This problem was eventually remedied by the inclusion of two one-month periods of active rest each year. When these two breaks were taken he found that his training had been much more consistent. However, he still wasn’t making his breaks easy enough for a proper recovery. How hard it is for a dedicated athlete to take a proper rest!

After the 1968 Olympics

Following the October Olympics, Hill returned home to his family (two children) and his full-time job. He continued training as he had a “big race” on November 9: an attack on the British One-Hour Record. Helped by Jim Alder and Ron Grove, he went through six miles in 27:53. On his own after seven miles, he soon realized that the WR for Ten Miles was within his grasp. So he went for that, achieved it in 46:44.0, and thought that was enough. He kept on jogging as he had to finish the full race. After half a lap, Don Shelley came by (he’d been lapped twice) and took a partially recovered Hill with him. Thus Hill still got British records for 20K (58:39.0) and One Hour (12 miles, 1,268 yards).

Possibly still on a high from his good Olympic run, Hill didn’t take sufficient rest. He did have an active rest for a month, but as he has written, “perhaps 60 to 80 miles…had not been low enough for a recovery after my long summer.” (2:16) He got back to hard training in December. In the cross-country season, things didn’t go too well, although he won the Lancs. for the eighth time. He was a little below par in the Intercounties (5th) and the Northern (11th). Then he broke down: “For three weeks I suffered, ill with my chest and running awkwardly and painfully with my leg and knee.” (2:20) He ran 15th in the Nationals though still under the weather. His cold wouldn’t shift, but he continued with two more races: a road relay and the AAA 10 Miles, which he won in 47:27.0. At this point he realized he badly need a break, so he took an unprecedented six weeks of active rest (“I just jogged”).

Trials for the 1969 Euros

|

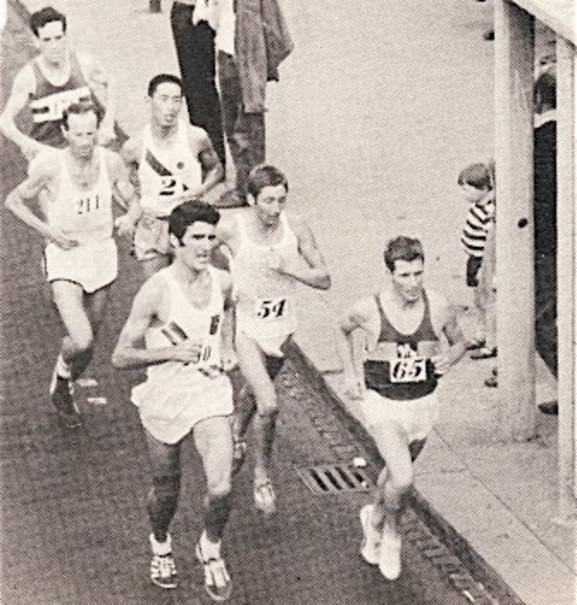

| Maxol Marathon. Hill runs between Clayton (50) and Adcocks (65). |

Refreshed, he began to train hard again. In June he averaged over 125 miles a week, building up for the Maxol Marathon in July, which would be the selection race for the Euros. A victory in the World Games 10,000, after a fall and a spiking with seven laps to go, was a big morale booster. There was an impressive field for the Maxol, with Derek Clayton (2:08:33.6) as the fastest entrant. After five miles, Clayton was already putting in short bursts. By 10 Miles (50:10) only Hill, Adcocks and Clayton were in the lead group. First Adcocks and then Clayton dropped off Hill’s pace. At 15 miles he was on his own and he hung on for a 1:58 victory over Clayton and a PB of 2:13:42. He was on the British team for the Euro Marathon.

Next up was the 10,000 trial for the Euros. He didn’t want to run this event at the Euros, but he still came third in 28:39.2. This led to him representing Great Britain in a match against the USA. His partner was Jim Alder; their opponents were Frank Shorter and Kenny Moore. Hill was in control throughout and used his speed on the last lap to win in 29:07.2 from Moore (29:08). Three good runs over 10,000 on the track and a marathon PB showed he was in peak form.

European Marathon Champion

|

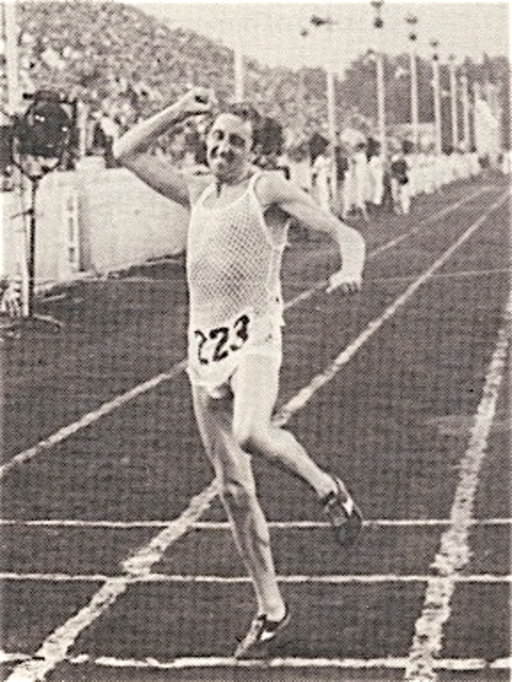

| European MarathonChampion |

For the next five weeks, he prepared for the Euro Marathon in Athens. A nippy 3,000 in 8:16 gave him a lift. In the heat of Athens he prepared carefully, carrying out his new carbo-loading pre-race diet. Everything went well in his final preparation. With the temperature in the 80s for the 4pm start, he began very slowly, but by 2 miles he was with the leaders. Farcic then took off, but no one went with him. After the first drinks station, Roelants went after Farcic, but Hill didn’t go with him. Instead he used his instincts to run his own pace, “the best speed I could keep without folding.” (2:51) Ahead, Roelants had passed Farcic.

Soon after 12 miles Hill caught Farcic, who held on until 15 miles. Then Hill was on his own in second—until Jim Alder caught him at 17 miles. He let Alder go ahead: “I had no intention of trying to stay with him,” he wrote. “I was going fast enough to know that I would finish.” (2:52) Alder got only 30 yards ahead and the gap stayed the same for a while. At the top of the last uphill, Hill quickly caught Alder and sped away downhill. He felt happy that he was going to be second. With a mile to go, he suddenly saw Roelants ahead. The Belgian was clearly in trouble, looking around constantly. Hill passed him with 1K to go and went on to a clear victory. He was European Marathon Champion, his first major title. His time was good for the heat: 2:16:47.8. He had a 34.4 second lead over Roelants and 78.0 over Alder. He had raced conservatively, always concerned about finishing. In fact, he was surprised at his victory.

Fukuoka Marathon

Back home, Ron made an abortive attempt on the 30K WR. After the organizers were unable to give him the proper lap times, he eased up, thinking he had no chance of the record. When he finished he was amazed to learn he was only 6.8 seconds outside the WR with 1:32:32.2. Next, he took a month’s active rest and then prepared for the Fukuoka Marathon in Japan. Clearly, he would not be doing his regular build-up for the cross-county season.

With two hard marathons in the previous five months, Hill needed to show a lot of resilience in Japan. In pouring rain, He watched Canadian Jerome Drayton take an early lead. As in the European Marathon, he bided his time, and at the turn he wondered if he had let Drayton get too far ahead. With nine miles to go, while running in the chasing group of ten, he finally realized that Drayton was uncatchable. In the last miles, he was in a tussle for second place with two Japanese runners, Garrido and Tanimura. It was Tanimura who pushed Hill the most, but the Japanese was not strong enough when Hill made his effort coming into the stadium. He finished in another PB with 2:11:54.4, just 42 seconds behind Drayton and nine seconds ahead of Tanimura. It was a fine ending to a very successful year. Clearly Hill had benefited from the long six-week rest in the spring.

Boston Marathon Victory

After his omission from the 1969 England cross-country team, Hill had lost some of his interest in cross-country, which had been his first love. He couldn’t keep his E. Lancs. and Lancs. titles, finishing second in both races. In the Northern he was only 10th, and in the Nationals he was 11th. But all the time he was putting in the miles, doing 120 to 130 a week with the Boston Marathon in his sights. It was a hard winter. He only eased off a little prior to Boston, dropping to 107 miles before the AAA Ten Miles. He posted a good time (47:35.2), but Trevor Wright beat him with 47:20.2.

In the Boston Marathon, he decided to go with Drayton early on. This was a notable change from his tactics in Fukuoka, when he let Drayton make an early break. At five miles he had dropped the Canadian and was facing 21 miles on his own. Not long after, Drayton was back with him. Soon after ten miles, Hill could feel Drayton weaken and left him again. He still ran conservatively up the many hills. After being told he was half a mile ahead, he learned at the top of Heartbreak Hill that his lead was only 200 yards. Using all his experience to keep going, he held on well to win in 2:10:30.1, yet another PB. Hill was the first Briton to win the Boston Marathon.

Following this great win, Hill took a four-week active rest. Then he embarked on a ten-week build-up to the Commonwealth Games Marathon, his place on the team having been assured by his Boston run. His mileage built up to 140. One week he was down to 108 for a 10,000 race against E. Germany. His 28:40 for third showed he was in good shape.

Commonwealth Champion

|

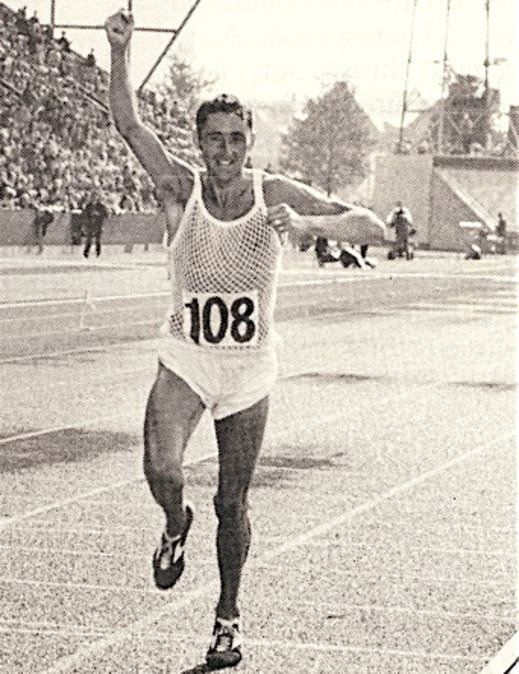

| Commonwealth Champion and first man under 2:10. |

The Commonwealth Marathon in Edinburgh started fast, with Clayton leading Hill and three other runners. At five miles Clayton fell back. Hill, feeling good, pushed up an incline and then waited for Clayton and Ndoo of Kenya at the top. A couple of miles later, he went clear and passed 10 miles in the very fast time of 47:45. At the turnaround he could see his lead was not that great: Drayton, Alder and Wright were still close. Feeling good, he passed 15 Miles in 72:18. But at 16 miles the pace started to tell. He managed to maintain his speed, passing 20 miles in a very fast 1:37:30. Soon after he learned he was 1:20 ahead. His great strength held him together and he finished well clear in 2:09:28, a PB that made him the second person ever to run under 2:10. Behind him Jim Alder ran 2:12:04 and Don Faircloth 2:12:19. Four consecutive successful marathons, each improving his PB, showed that Hill had finally mastered his training program and big-race preparation.

The rest of 1970 was an anti-climax. He disappointed in a special 30K race set up for him at Crystal Palace. He was able to stay with the leaders until 13K but then couldn’t respond to Jim Alder’s surge. While Alder went on to break the world record, Hill never gave up and finished third in a good time of 1:32:17. Still, it was clear that he was past his peak.

Breakdown

At this time, Hill decided to experiment with even higher mileage by inserting a third session in his day—during his lunch hour. He ran consecutive weeks of 131,132,152 and 164. After this he had to taper off for the Fukuoka Marathon. In this race, things went well for the first 10 miles, but then his legs seized up and he had to watch the leaders move away. He was very unhappy with his 9th place (2:15:27) and clearly needed a good rest. In fact, he dropped down to two-mile runs and went to watch, rather that run in, the Lancs. All this indicated that the increased mileage had been too much for him.

Hill developed a chest infection, which lingered a long time. Nevertheless, he ran the Northern (26th) and the Nationals (82nd) while still infected. When he got his sixth sore throat since December, he finally decided to take a major rest. From the end of March 1971 he cut his mileage to 88, 56, 42, 60 and 80. Then he had six weeks to build up for the European Trials Maxol Marathon. Despite a “disastrous” 10,000 in 30:24.6, he felt confident after a half-marathon win in 1:07:06.

In the Maxol he felt good enough after three miles to go to the lead. Only John Newsome went with him. Then after a couple of miles Jim Alder led a group that joined him. So he took off again; only Trevor Wright and Bernie Plain went with him. Plain was dropped at 15 miles, but Wright was able to stay with Hill until the 23rd mile. Hill was a comfortable winner in 2:12:39, with Wright clocking 2:13:27. He had qualified for the European Marathon, but he had only nine weeks to prepare—not time enough for a rest and a build up.

European Bronze

Hill did manage one week of active rest, but then he had to train hard. His right leg was hurting. And then on arrival at Helsinki he caught a stomach bug. Still, he felt “bouncy” in the early stages of the race. There was a big pack at the front until 20K, when Roelants took off. Hill decided not to follow, but his team-mate Wright did. Soon Lismont joined the two leaders, while Hill waited in the hope that they would come back to him. Hill “woke up” at 30K, soon passing Roelants and moving into third. But he was unable to catch Lismont (2:13:09) and Wright (2:13:59.6). He was not happy with his third place (2:14:34.8), telling the press, “The bronze medal was only marginally better than a kick up the backside.” (2:156) Hill, who was frustrated with his tired mental attitude during the race, felt strongly that scheduling the Maxol Trial so close to the games had ruined his chances of a gold medal. “I really blamed the selectors for losing me that gold medal,” he wrote later.” (2:157)

Munich 1972

|

| Munich: Hill tries to hold off Don McGregor |

Hill’s build-up for the Olympics now saw him racing over the country in Europe. He also ran a half-marathon in Mexico. His mileage stayed high: 127,131 and 128 in February. He was running well and had thoughts of making the England cross-country team, but he had a bad race in the Nationals, finishing only 53rd. Then his thoughts turned to the Olympic Trials on June 4, his request to be selected on past performances having been rejected. The trial went well for him: he was first British runner, finishing second in 2:12:51 behind Philipp of Germany.

Hill managed to keep his mileage high (120-130) until he went to St Moritz for three weeks of altitude training. From there he went straight to Munich, just a few days before the Olympic Marathon. The race started slowly: 15:51 for the first 5K. Hill was feeling “rough” and couldn’t go when Clayton and Usami made their move. Soon more runners passed him. However, the leaders slowed and came back to Hill, and he took the lead. Just after 10K (31:15) Clayton moved away again, while Hill fell back. He was feeling poorly, but was relieved that the leaders were not too far ahead. At 15K he was 13th and stayed in this position up to 20K (62:41). Between 30K and 35K he moved up seven places and held this position till the end, though strongly challenged by team-mate Don McGregor near the end. Sixth in 2:16:31 behind the winner, Shorter (2:12:20), he was only 1:22 out of a medal.

So why did he not run his best in this important race? Tim Noakes, in Lore of Running, spends ten pages answering this question. He gives 13 possible reasons. The most important of these was the fact that Hill did three weeks of altitude training just before the Games. He had never done this type of training before, so it must have been a shock to his system, especially since he trained too hard the first few days. Additionally Hill didn’t understand that benefits from altitude training don’t occur until after two weeks back at sea level. Noakes also thought that Hill had run too many marathons and had become what he termed “marathon punch-drunk.” For some reason Hill changed his preparation for this race, a preparation that he had painstakingly developed over many years. Not only did he carry out altitude training for the first time, but he also increased the length of his build-up by 25%. He even swore off beer during this preparation. The scientist in Hill couldn’t stop experimenting.

Disappointments

After the Olympics, mental and physical exhaustion affected Hill: “For the rest of the year my training had no direction. My mileage yo-yoed between 60 and 90 miles per week.” (2:242) After turning down an invitation to run the Fukuoka Marathon, he was back in full training by January, building up to 100 miles a week. Despite feeling very tired, he still raced cross-country regularly. He was 10th in the Lancs., 5th in the E. Lancs., 11th in the Northern, and 30th in the Nationals. An erratic summer of international races followed. A win in the Enschede Marathon in 2:18:05, in hot conditions, made him think that he didn’t need to do such high mileage. After a miserable 17th in Commonwealth 10,000 trial, he lined up for the Marathon trial. Again he started slowly, catching the leaders at 4.5 miles. At 18 miles he let Ian Thompson get away— he didn’t know who Thompson was. Hill knew 2nd would qualify him and finished comfortably in 2:13:22.

In the 1974 Commonwealth Games Marathon in New Zealand, Hill stayed in the lead pack until 5K (15:12), but was 10 seconds adrift at 10K (30:25). In trouble with a painful foot, which got worse as the race went on, he finished 18th in 2:30:24.2. Back home there were suggestions of retirement, but he rejected them outright: “I would never retire.” (2:269) Instead he looked forward to the Euros in September. For five weeks he ran a mile a day with his injury and even cycled to work to maintain some fitness. But he was unable to get into proper shape for the Euro trial, finishing 6th in 2:21:36. It was the first time since 1962 that he had been out of a major games. The only consolation was a win later on in the Szeged Marathon in Hungary with 2:19:27.8.

Marathon Specialist

|

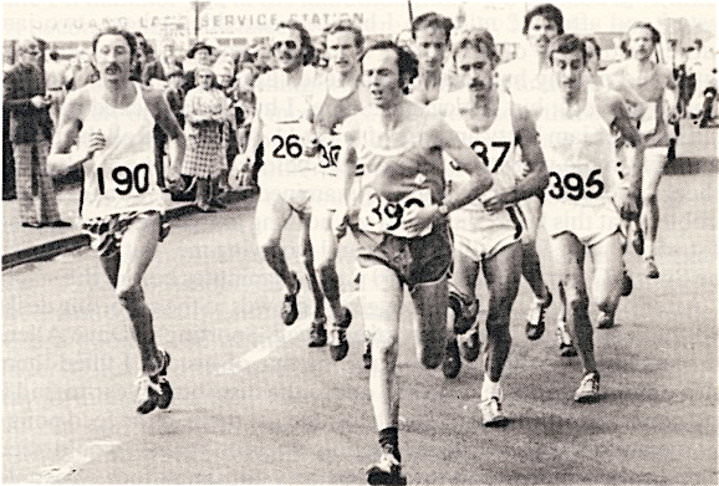

| Hill (190) trying to qualify for the Montreal Olympics. Barry Watson leads from Thompson and Wright (395). |

His next goal was the 1976 Olympics in Montreal. In 1975 he continued to race regularly with his mileage average around 70. His racing schedule was now organized around marathons. In November 1974 he won the Maryland Marathon with a reasonable 2:17:23. After this he had a very abbreviated cross-country season: 6th in the E. Lancs., “20-something” in the Northern and 43rd in the Nationals. All the while his focus was on the Boston Marathon, where he finished an impressive fifth with the promising time of 2:13:28.

It looked like he was able to run good marathons on a lower mileage as he had two wins in the summer of 1975: the Ankara Marathon (2:21:25) and the Debno Marathon (2:12:34.2). Then he was off to Montreal for the Pre-Olympic Marathon. It was held in 100-degree heat. He was in the lead with two other runners at 40K, but ran out of gas at that point and finished third (2:26:01.4), only 15 seconds behind the winner Mizukami of Japan. Maybe he was saving himself for the Enschede Marathon four weeks later. This marathon saw his best win of the year as he crossed the line with a 2:43 lead and a time of 2:15:59.2, a good time for a hot day. Olympic Trials

It was time for a rest and then the build-up for the Olympic trial. Over the winter he again ran the Maryland Marathon (2nd in 2:17:06) and ran cross country in the Lancs. (13th) and in the Nationals (107th). Then after three weeks of active rest, he ran sixth in a half-marathon (1:04:10) and third in another a week later (1:06:19). He was confident of a place in the Montreal marathon team.

The early pace in the Olympic Marathon Trial was fast. The leaders covered the first five miles in under 25:00, and Hill, who started slowly, found it hard to get up with them. When Ian Thompson and Barry Watson took off at 7 miles, Hill could not go with them. He stayed in the second group of seven. At 13 miles the chasing group was down to five, trailing the two leaders by 40 seconds. The crunch came at 17 miles when Norman, Plain and Angus dropped Hill. He was now alone, but he kept pushing. At 21.5 miles he passed Plain and then Thompson to move into 4th. But that was it; he couldn’t catch the next man. His Olympic dream was gone: fourth in 2:16:59.

Running Life Continues

Hill continued racing over the summer with a 3rd in the Poly Marathon (2:18:14) and a 4th in a marathon in Belgium (2:23:38). The next month he was 10th in the New York Marathon (2:19:43), and the month after that 3rd in the Maryland Marathon (2:20:23).

By now his expanding business was taking up more and more of his time. Still, he ran a low-key but full 1977 cross-country season. And after marathons in South Africa and Holland, he ran an impressive third in the Poly Marathon (2:16:37), only two minutes behind winner Ian Thompson. This was followed by a 9th in the Enschede Marathon, an 18th in the New York and a 4th in the Maryland. He continued to run marathons in the following years, his times gradually rising into the mid-2:20s. There was no way he was ever to stop racing. And now thirty years later in 2012 he is still at it. In 2011 he ran 1,455 miles (2342K) making his lifetime total 155,916 miles (250,922K). In January 2012, at the age of 73 he ran a 5K in Austin Texas in 25:59 and recorded 31 miles for that week.

Conclusion

|

| 1980: The racing goes on and on. |

Hill’s contribution to distance running is considerable. With no more than average physical talent, he became one of the world’s best distance runners in track, cross-country and road running. An insatiable desire to find the ideal training program pushed him to physical and mental limits. Many have criticized him for over-training and for running when injured or sick, but these critics have not understood the mental demands that Hill put on himself. He believed that the only way to find his limits was to set himself a strict 13-sessions-a-week schedule and stick to it religiously year after year. He wasn’t masochistic, nor was he obsessive: “It’s symbolic. I’m saying that nothing’s going to stop me. Even when things get tough, nothing’s going to stop my training. And I’m hoping some of his will carry over to a race.” (Prokop, Runner’s World, 1971, p.12)

Hill was always experimenting. His two books detail thoroughly how he tried to find the best way to prepare himself for competition: “The mistakes I made are there for runners to learn from and hopefully not repeat.” (2:423) He was an innovator in many ways: barefoot racing, string and mesh vests, freedom shorts, Trackster winter-training pants, perforated road shoes built from a spike last, shaved legs, and above all carbo loading. Unusually for a dedicated runner, he was also a bon viveur who quaffed a lot of beer (much of it brewed by himself), smoked intermittently and enjoyed socializing. He has certainly lived life at a fast pace, and few people have been able to keep up with him!

4 Comments