PROFILE: JIM RYUN

b. 1947

Once every generation or so, a prodigy appears on the running scene with a talent far above his contemporaries. American Jim Ryun was one such prodigy. At 17 he broke the 4-min barrier and represented the USA in the 1964 Olympics. At 18 he ran 3:55.3, breaking the American Mile record. Today, almost 50 years later, he still holds five of the six fastest mile times in U.S. high school history. In his five years at the top, he consistently performed at the highest level, breaking four world records. Only in the Olympics did he fall short of his expectations. In his three Olympics his best was a silver medal.

Finding His Sport

|

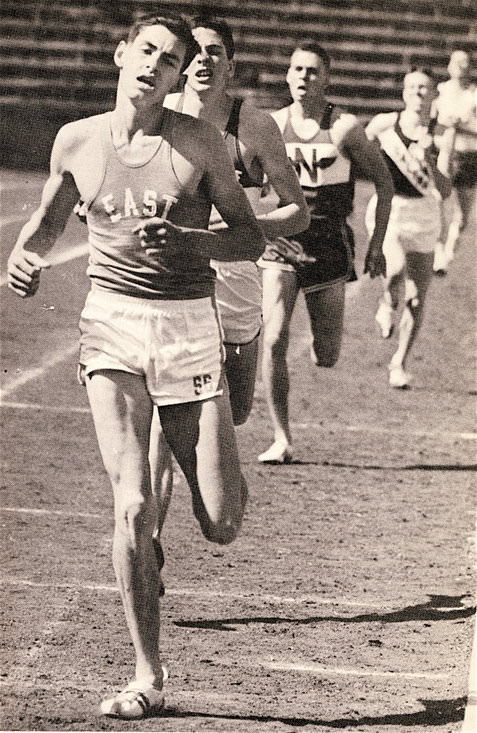

| Ryun runs a 4:21.7 PB. |

A frail, gangly child with allergies, Ryun was nevetheless attracted to sports. He joined the Little League in Wichita, Kansas, as soon as he was old enough, but he never excelled. After watching athletes on the track at Southeast High, a block from his home, he tried track when he went to Junior High. But he was unable to make the school team in either the hurdles, sprints or 440. Later, at High School in 1962 he heard an inspirational talk by the school coach Bob Timmons. Inspired by Timmons’s claim that hard training would pay dividends in cross-country, he decided to try out for the team. In his first time-trial for a Mile he was 13th in 5:38—not good enough for even the B team. An 11:51 Two Miles finally gave him some encouragement. He dropped his time to 11:23 and then won a B competition. After this, Ryun was put in the A team and ran a 10:36. Coach Timmons was impressed and watched the young 15-year-old improve to become the school’s top cross-country runner.

Ryun continued training under Timmons through the winter of 1962-3. In his first track meet he almost won the Mile, clocking 4:32.4. Next he ran 4:26.4, winning with an impressive kick. Ryun improved again to 4:21.7 and ran the same time again for a victory in the Kansas Relays, covering his last lap in 60.7. Nevertheless, Coach Timmons insisted that his new star was winning because of his cross-country stamina, not his speed.

His rate of improvement continued to amaze. Five days before he turned 16, his time came down again to 4:19.7. The next month he ran 4:16.2 and then a stunning 4:08.2 followed by a 4:07.8. His speed was improving too: 1:53.6 and 50.5 for 880 and 440. He finished off his incredible first track season with a 9:13.8 Two Miles, the fastest ever by a US schoolboy.

Heavy Workload

Timmons was already working Ryun really hard in training. And he pushed him even harder the following winter with twice-a-day sessions building up to 110 miles a week. One famous session was 40x440 in 69 with a 90-second rest. All this was an incredible workload for a 16-year-old. In an interview published in 2008, Ryun told Jim Denison, “Those workouts were incredibly intense, and probably far beyond what was necessary to be a miler…. It’s a miracle I didn’t get seriously injured in my first three years of running.” (Bannister and Beyond, p.91)

Ryun later described Timmons’ approach as “centering…around thorough planning, determined sacrifice and hard work—all given direction and purpose through the use of specific goals for each runner. The very backbone of his program was rooted in goals.” (Jim Ryun, In Quest of Gold, p.19) Timmons goals for Ryun were very high, much higher than Ryun thought possible: “But I was willing to go along,” he wrote later. (Gold, p.19)

Ryun later described Timmons’ approach as “centering…around thorough planning, determined sacrifice and hard work—all given direction and purpose through the use of specific goals for each runner. The very backbone of his program was rooted in goals.” (Jim Ryun, In Quest of Gold, p.19) Timmons goals for Ryun were very high, much higher than Ryun thought possible: “But I was willing to go along,” he wrote later. (Gold, p.19)

Ryun progressed gradually through 1964 high-school track season, ending up with a 4:06.4 Mile, a 1.4-second PB. This performance qualified him for the big California meets to race the top American milers. At Modesto he showed he could run with them, finishing third behind O’Hara and Burleson with a huge PB of 4:01.7. In his next race at Compton, the field was even stronger with Jim Grelle entered. And although he finished back in eighth position, he was timed at 3:59.0. He thus became the first schoolboy to break the 4:00 barrier—just ten years after Bannister’s 3:59.4. The Olympics were only four months away. Was it possible that this high-school kid, who still had a newspaper delivery round, could qualify for Munich?

First Olympics

Showing no signs of fatigue from an already long season, he ran a brilliant fourth in the AAU 1,500 behind winner O’Hara, almost beating Grelle and Burleson. His time was better than his 3:59 Mile: 3:39.0. Two months later, sporting his first crewcut, he lined up for the Olympic Trials. O’Hara and Burleson still looked too good for him, but he had a chance of beating Grelle, who had only been finishing ahead of him by fractions of a second, for the third and final place on the US team. After a 59.8 first lap, the pace slowed to 2:04. At the bell all six runners were bunched. San Romani was the first to go, and Grelle chased him. Ryun was back in fifth: “Coming into the final turn, I didn’t think I could do it. But then I could feel something happen. I don’t know where it came from, but I had the strength.” (Cordner Nelson, The Jim Ryun Story, p.75) Now running in the third lane, he had to pass two runners in the final 100 to qualify. He soon caught a tired San Romani, and with 40m to go he was only two feet behind Grelle. He passed Grelle in the last ten meters, both runners finishing in 3:41.9. Ryun had run a 53.5 last lap and had show great competitive grit to qualify for the Olympics.

Up to this point Ryun’s career was like a fairy tale. Jim's mother was quoted as saying: “I don’t want anyone to wake me up yet if this is all a dream.” (Nelson, p. 95) But in Tokyo reality set in. He did well in his heat with a fourth place in 3:44, but in his semi he was left standing when Snell poured on the pace. He finished last in 3:55.0. Though he didn’t offer any excuses, he had been dealing with a virus for two weeks. As well, it had been a long season for the 17-year-old. Now he had to go back for his last year in high school. “I was extremely depressed and could hardly wait to get home, away from the Olympics,” he wrote later. (Gold, p.33)

New Coach

Back home in Kansas, Ryun had to deal with the first major setback in his career. As he wrote later, “Tokyo presented me with my first taste of failure in a long time.” (Gold, p.32) The high-school boy who could do nothing wrong on the running track had lost a little bit of his magic. On top of this, he had to deal with the departure of his coach: Timmons had accepted a job at the University of Kansas. But his resilience was still there. And despite having to catch up on a lot of schoolwork, Ryun was soon back to his ruthless training schedule. Under a new coach, JD Edmiston, he ran the cross-country season, had a lay-off with an injury, and then came back for the high-school track season, finishing up with a PB 3:58.3 Mile.

But it was the senior season that he was focusing on. His first race was in Modesto, where he had made his breakthrough the year before. His old rivals Grelle and Weisiger were in the field. Also running was Olympic silver medalist Josef Odlozil of Czechoslovakia. After laps of 59 and 61 in the pack, Ryun showed a new level of confidence by taking the lead. He led at the bell in 3:01.9. His lack of experience showed on the back straight, where he let Grelle pass him on the inside. Still, Ryun was not to be beaten, for he edged by Grelle in the home stretch to win in 3:58.1. It was his first victory in a major race and yet another PB.

Races Against Snell

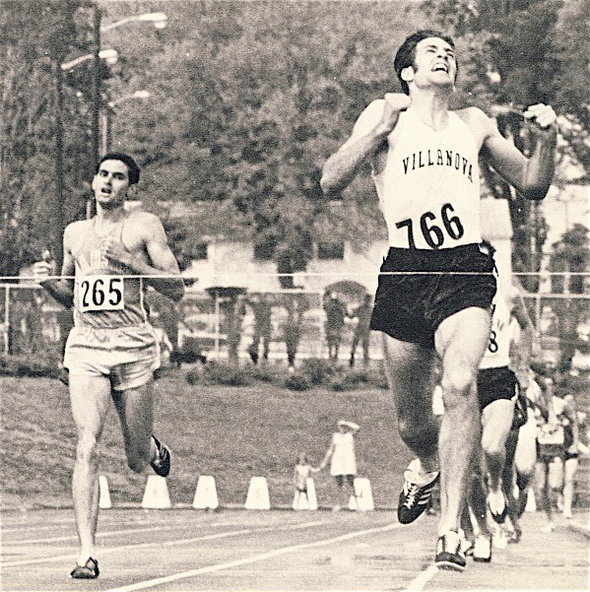

|

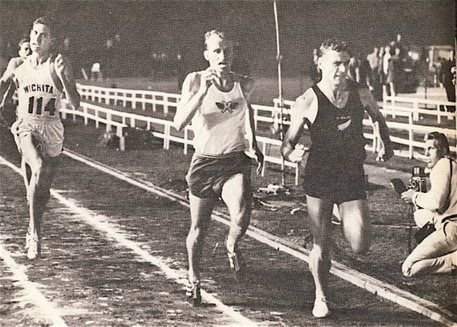

| Finishing third in his first race against Peter Snell. Grelle is second. |

Next, after his graduation ceremony in Kansas, Ryun returned to California for his next race in Compton. This time the great WR-holder Peter Snell was in the field. Ryun planned to wait for the New Zealander’s final sprint and match it over the last 200. He was well placed in third at the start of the back straight on the last lap, but Snell went early and was 6m up before he could react. Behind Grelle, he chased the Kiwi round the final bend. This time, Grelle not only held off Ryun but also nearly caught Snell. Ryun had to be satisfied with a close third, albeit in another PB of 3:56.8.

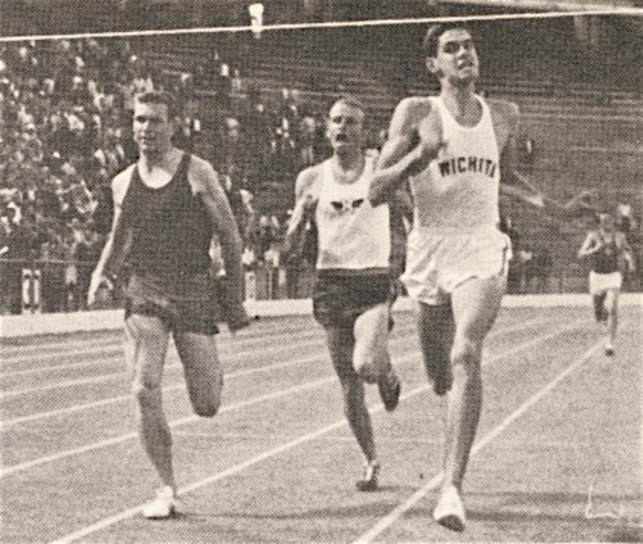

He was able to have another go at Snell in the San Diego AAU meet. “I wasn’t nearly as afraid of Snell at San Diego as I had been at Compton,” he said later. “I thought after Compton I could beat him because he wasn’t that far ahead of me [0.4 of a second]. He had just got the jump on me too soon.” (Nelson, p.134) After a lot of jostling in the first two laps, Odlozil surprised the field in lap 3 by bursting into a 5-yard lead. Grelle again led Ryun in the response to the break, and they were within 2m of the Czech at the bell, with Snell right behind them. Ryun moved outside Grelle on the first bend and then made his move “not quite going all out” (Nelson, p.135) just before the back stretch. Grelle was back on his shoulder with 220 to go, but Ryun held him off round the final bend. They sprinted neck and neck in the straight before Grelle weakened. Behind these two, Snell was coming through and Ryun had to find a little more to hold him off. He responded to Snell’s challenge and won 3:55.3 to 3:55.4. With a last lap of 53.9, he had run a new American record and was now fourth fastest all-time.

|

| Winning his second race against Snell. |

It had been an amazing competitive performance. Snell himself paid tribute to the 18-year-old: “Ryun’s got it—the quality which goes to make a champion…. Ryun ran a perfect tactical race.” (Cordner Nelson and Roberto Quercetani, TheMilers, p.307) Later he wrote of Ryun, “He ran with real confidence, kept a lot back after making his initial break, and forced Grelle and me to run wide round that last bend.” (Peter Snell, No Bugles No Drums, p.218) Some of the credit for Ryun’s fine tactics should go to his new coach J.D. Edmiston, who had taken over from Timmons for Ryun’s senior high-school year. Ryun has written that he “immediately developed a good relationship” with Edmiston and that by the summer of 1965 “even the stiff national competitions did not frighten me to quite the same extent they had.” (Gold, p.32)

After this magnificent race, the rest of the 1965 season was an anti-climax. Nursing a painful knee he ran in Kingston, Kiev, Warsaw and Augsburg, earning points for the USA team in international meets. Then it was time for a fishing trip and some rest.

Back with Timmons

At the University of Kansas and again with Coach Timmons, the freshman settled into a daunting new regime: a 5:15 am run; classes; a long afternoon training session; and studies into the night hours. As a sporting celebrity, he now had to deal with reporters and promoters all the time. Every time he raced a Mile, indoors and outdoors, the crowd expected a sub-four. Still, he managed to train well while fulfilling his varsity obligations in cross-country and track. Early in the 1966 track season, he posted an encouraging 3:55.8 in the Cunningham Mile. In his next race, a Two Miles, he came up against Kip Keino for the first time. Jim Grelle was also in the race, and he was the one who nearly beat Ryun, both of them recording a fast 8:25.2 in front of Keino. Clearly Ryun was stronger than ever with this 22-seconds PB, which was only 2.6 off Jazy’s WR. He almost broke the Frenchman’s Mile mark in his next race with a 3:53.7 PB at Compton.

World Records

|

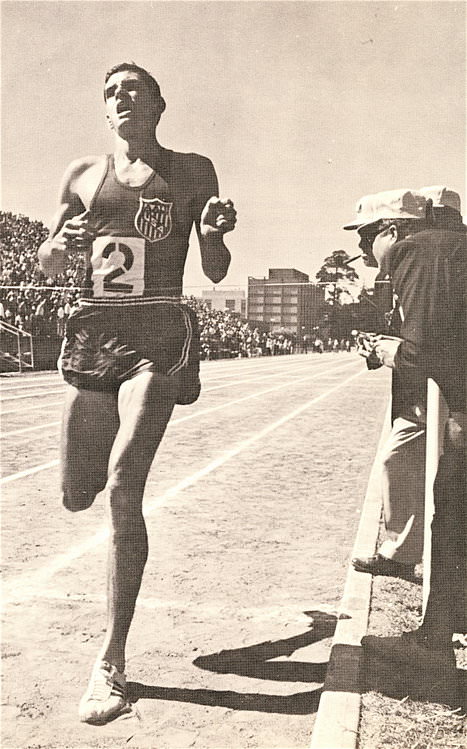

| World-record Mile in 3:51.3 |

But it wasn’t the Mile WR that he broke first. Running an 880 in the UST&F Championships, he surprisingly broke Snell’s WR of 1:45.1 with 1:44.9. This was achieved after a 1:51 heat two hours earlier. After a 53.3 first lap, he took off on the back straight, running the last 220 in 25.5. Then in Berkeley he attacked Michel Jazy’s Mile WR of 3:53.6. After being taken through in 57.9 and 1:55.5, Ryun had to go it alone on the back straight of lap 3 after he felt the pace slowing: “I…lengthened my stride, trying to hold a steady pace.” (Gold, p.49). He reached the bell in 2:55.3 and needed a 58.3 last lap to break the record. But the fast pace was hurting: “I was gradually tying up.” (Gold, p.49)

He passed 1,500 in 3:36.1 (2nd fastest ever) and looked really good over the last 120, covering the last lap in 56.0 for a 3:51.3. He was 6.7 seconds ahead of the next runner, Cary Weisiger. “I didn’t know it was a WR until they announced it over the loudspeaker. I was surprised,” Ryun recalled later (Milers, p.320). His 1966 season finished with a 1:46.2 880. It had been an amazing year: two of the three fastest 880s ever run, two of the three fastest Miles ever run, and one of the three fastest 1,500s and Two Miles. (Milers, p.320)

Wes Santee, a Kansan who came close to running the first sub-four Mile more than a decade earlier, had this to say about Ryun after his Mile WR: “Jim is capable of running 3:50 any time now. The problem is Jim has already conquered the world as a teenager. If he can sustain a burning desire to improve at track, there’s no telling how fast he can run. But I’m afraid the desire will cool. From now on, other things may look more important to him. What has he to look forward to?” (John Lake, Jim Ryun, Master of the Mile, p.156) Santee’s main point is profound, but he doesn’t take into account the challenge of the Olympics, and it was the thought of a gold medal that helped keep Ryun’s fire burning.

Two More World Records

Injury forced sophomore Ryun to miss almost all of the cross-country season. As well, he avoided most indoor meets. He did however run 1:48.3, 3:58.8 and 8:44.2 indoors for 880, Mile and Two Miles. In his first major outdoor race he ran a fast 3:54.7 Mile. Two months later, after a week’s altitude training, he set out to break 3:50 in the AAU Championships. He led from the gun, but his legs felt heavy. After laps of 59 and 60, he didn’t think he could break any records, yet alone 3:50. His next lap was 58.5 for a 3/4 time of 2:57.4—well below the pace for a sub-3:50. Then something surprising happened: he sped up with a 27.4 220, and even increased this pace to the tape. He had run a new WR of 3:51.1 and a last lap of 53.7. It was an amazing solo run. His old rival Jim Grelle was quick to appreciate Ryun’s achievement: “It’s very hard to run by yourself, like he did tonight. His build-up on that last lap was amazing.” (Milers, p.329) Ryun claimed later that he didn’t feel as tired after this WR as he had following his 3:51.3 WR the previous year.

Next up was an attack on Elliott’s 3:35.6 1,500 WR. Ryun chose the meet against the British Commonwealth in LA as Kip Keino was in the race. After a very slow start Bailey of Canada took the field through 440 in 60.9. Keino then took off with Ryun on his heels. It was a two-man race. They covered the next lap in 56.0. Keino continued to push, but he couldn’t escape Ryun. They passed three laps in 2:55, well on schedule for a WR. Ryun moved up beside Keino on the back straight. His attack before the last bend was unanswerable and broke Keino completely. When Ryun broke the tape in a new WR time of 3:33.1, he was 25 yards ahead. He had covered the last two laps in 1:51.3 and the last lap in 53.9. His Mile and 1,500 WRs had been achieved in two totally different ways: once through front-running and once through tough competition.

Ryun’s competitive ability was evident again just over a month later, when he beat Keino over a Mile in London: 3:56.0 to 3:57.4. After that, he had just one more race in Europe against West Germany. He was teamed with Grelle against two great German runners, Norpoth and Tummler. In this race he showed astonishing speed on the back stretch of the last lap, covering 100m in 11.6. He then pulled away even more for a convincing four-second victory over Tummler in 3:38.2. So Ryun’s 1967 season confirmed even more strongly that he was the premier Mile/1,500 runner in the world. He was faster than anyone else by 3.6 seconds in the 1,500 and by 2.0 seconds in the Mile. And he was unbeatable.

Mexico Olympics

Ryun’s 1967 season was perfect preparation for the 1968 Olympics. The only trouble was that the Mexico City venue was at high altitude (7,350 feet/2,240m). Well, not the only trouble because injuries began to plague him. First it was his ankle and then his hamstring. The situation got serious in May when he contracted mono. While resting, he lived at 6907 ft in Flagstaff, Arizona. Ten weeks later he was able to run 1:47.9 for 880 at altitude, and he was then able to qualify comfortably for Mexico with a 1,500 time of 3:49.0 after running the last 800 in an incredible 1:50.8.

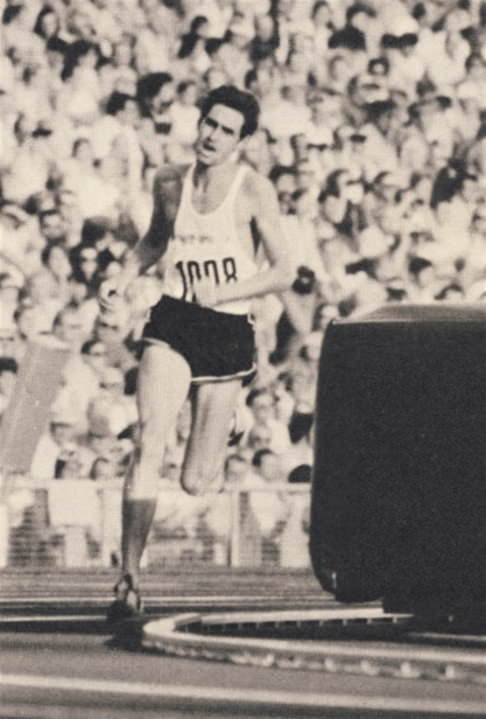

|

| Mexico Olympics: Three seconds short of a gold medal as Keino wins. |

Ryun’s main opponent for the Olympic 1,500, Kip Keino, was also having troubles. Over the summer of 1968, he had suffered from stomach pains in several races in Europe, but in his last race before the Games he ran an impressive 3:55.5 Mile. The stomach pains came back in the 10,000 early in the Games, causing him to collapse near the end of the race. Despite this,, he lined up for the 1,500 heats against doctor’s orders and made the final without trouble.

So for the Olympic 1,500 final, both Ryun and Keino had concerns about their conditioning—Keino with his stomach and Ryun with his erratic preparation. Ryun had previously shown his dominance at sea level, but the Mexico City altitude gave Keino a significant advantage. “How I prayed for a slow pace!” Ryun wrote later, (Gold, p.92) as he knew that if he started fast, he would soon be in oxygen debt. So he must have been severely shocked at the early pace when Kenyans Jipcho and Keino raced away with a 56 first lap. He was over two seconds adrift at 58.5 near the back of the field. Keino, well aware of Ryun’s finishing speed, knew his best chance was to make the race fast, thereby using his altitude advantage: “I prepared myself to have a big lead going into the final quarter,” (Milers, p.342). Keino led through two laps in 1:55.3 and looked like he already had the better of Ryun, who languished back in fifth place (1:58.5).

But Ryun wasn’t giving up. He put in a superb 57.7 third lap for a 2:56.0 time and fourth place at 1,200 behind Keino (2:53.4), Tummler and Norpoth: “I saw that the race was in danger of getting away from me and realized that, oxygen or not, I had to do something quick.” (Gold, p.93) Courageously he passed Norpoth on the back straight and Tummler on the final bend. But Keino was still over 10 meters ahead going into the final stretch, and he was not slowing. Ryun made no impression on Keino in the final 100m but maintained a comfortable lead over Tummler. He was 2.98 seconds behind Keino at the end, but his 3:37.89 time was really impressive at such altitude. “I could not have kept up with [Keino] and still have [had] any kick left for the finish,” Ryun admitted afterwards (Milers, p. 341). Still, he had run a brilliant race; no non-altitude runner could have run with Keino. A silver medal was a fine achievement, but it was gold he wanted. He would have to wait four years for another chance at that.

Breakdown

When he began the 1969 indoor season as a newly married man, another American prodigy was emerging to challenge him: Marty Liquori. Liquori had qualified for the Olympics as a schoolboy—just as Ryun had done in 1964. Soon after he was challenging Ryun in the NCAA indoor Mile; then in the NCAA outdoor Mile, he held off Ryun to win, 3:57.7 to 3:59.3. Clearly all was not right with Ryun. “I’d burned myself out; the competitive edge was gone,” he wrote later. (Gold, p.102) His hip was hurting, and he was having an argument with the AAU over his planned summer tour. He was “a bundle of nerves” (Gold, p.104) and the continual hassle from the press was making things worse. Ryun later said that “surviving the public’s and media’s expectations” was “harder than surviving [Timmons’] workouts.” (Denison, p.92) Finally something inside him snapped. He dropped out of the AAU Mile after 660 and then canceled his European trip. He didn’t run again for almost a year.

His long break from the rigours of training, racing and press coverage was restorative. He changed his major from business to photography, developed a social life, played tennis and racquetball, refinished furniture and started a family. His weight went up to 200 lbs.

After the birth of their first child, it was his wife Anne who got him out jogging. And soon the running bug got a grip of him again. The 1972 Olympics entered his thoughts. Then he made what turned out to be a bad decision—to move to Eugene: “One thing I hadn’t foreseen…was the pollen problem. My allergies hadn’t given me difficulties in Kansas for years, and I never gave them a though before moving west. My body began to react, causing my lungs and throat passages to swell.” (Gold, p.117) Nevertheless, he persevered with his training in Oregon.

Back to Competition

|

| Liquori defeats Ryun in the 1969. |

His first race in 19 months was an indoor Mile in San Francisco, which he won in 4:04 with a 56.5 last lap. Next came a surprising 3:56.4, which equaled the WR of Tom O’Hara. Then he went on to run 3:55 in the Kansas Relays outdoors. “My confidence had returned,” he wrote later. (Gold, p. 117) He was ready to tackle Marty Liquori, his heir apparent. It was a great race. Ryun followed Liquori closely as they ran 61 and 2:03. Liquori then upped the pace with a killing 56.7 lap. Ryun was still with him and waited till the last bend to move up to his shoulder. But he was unable to overtake Liquori in the final run-in, losing 3:54.6 to 3:54.8. After this rare defeat, Ryun’s allergies worsened to the point where he could manage only seventh in a Eugene meet. His allergies kept him out of the AAUs and his form in Europe was disastrous. He was tenth and last (4:17.3) in a Mile in Stockholm, “wheezing along, hardly able to breathe.” (Gold, p.121)

Two Moves

On returning to the USA, Ryun moved south to Santa Barbara, California, to escape the Eugene pollen. It had been a rocky 1971 season with many setbacks. Still, there was enough encouragement from his early races and an obvious reason for his poor form later on. As his allergies disappeared, Ryun settled down to a hard winter’s training. It went well, but on the indoor circuit he showed poor form. A 4:13 Mile was the last straw: he called up his old coach Timmons in Kansas. He decided that he was not doing well training and racing on his own. He needed the support of Bob Timmons, so the family moved--yet again--back to Kansas. A 4:19 indoor clocking in the LA Coliseum was another setback. Then in the Kansas Relays outdoors he ran 3:57. But this was followed by three more disastrous races. Clearly he was burned out and in crisis: “My insides wound tighter and tighter in knots. Every morning I awoke depressed. Timmie could hardly get two words out of me other than dour mumbling and despairing sighs.” (Gold, p.141) He took solace in his religion, and with Timmons’ encouragement he kept running.

Comeback

Hope returned when he ran a fine 5,000 in California (13:38.2). Next he won a good Mile race from Dave Wottle with a 3:57.3. This was a good build-up for the Olympic trials. For this race he decided to return to his old tactic of waiting until the last 200-300. The pace was slow: 62, 2:05.4, so the field was still together when Wottle made his move at 1200 (3:04.9). Ryun chased him down along the back straight, ran outside him round the bend and then powered past for a great victory in 3:41.5. His last lap was 51.5. He was back in form, but would he be as convincing in a fast race? The answer came three weeks later in Toronto. After being taken through in 59.0 and 1:57.6, Ryun moved into the lead, passed the bell in 2:57.2 and finished with a 55.6 lap for the third-fastest Mile ever (3:52.8). “At last I knew I had returned to peak form…I was ready,” he wrote later. (Gold, p.152)

Ryun had come back from a deep crisis, and he paid tribute to the role Timmons had played in this resurgence: “Yet when others had had given up on me, Timmie kept gently encouraging, never stopped believing, and helped me to believe in myself once again.” (Gold, p.150)

Munich Fall

|

|

| His last lap as an amateur runner.A dazed Ryun completes his Olympic heat after a tragic fall. |

Jim Ryun’s experience in his third Olympics couldn’t have been worse. It was a cruel irony that his fine 3:52.8 Mile in Toronto should have led to the disaster that awaited him. He was put in the wrong heat: for the seeding process, someone had entered his 3:52 Mile as a 1,500 time. And it was this heat that was his undoing. In jockeying for a position with 550 to go, he was spiked in his foot and fell with a runner from Ghana whose knee struck him in the throat and jaw. After lying stunned for several seconds with the Ghanian runner on half top of him, he managed to get to his feet. By this time the field was more that 100m ahead. To his credit, he still finished in 3:51.52, with no chance of catching the field in one lap. Despite two appeals, Ryun was eliminated. His Olympic hopes were over.

Almost immediately after returning home, Ryun signed with the ITA, the new pro track organization. He was a major part of this organization from 1972 to 1976 as both a runner and a promotional rep. His work involved a lot of traveling and his Mile performances were mediocre for him, varying between 4:00 and 4:08. An achilles problem, probably caused by so much board-running, finally led him to retire early in 1976. “I look back on my career with great feeling of accomplishment,” he told a press conference. “I’ve run for 13 years. That’s a long time. There’ve been some notable achievements, and I am proud of this period of my life. But athletes cannot sustain such a peak forever.” (Gold, p.192)

Ryun has been busy since he quit competitive running at 29. Apart from bringing up a large family and being deeply involved in his Evangelical Presbyterian church, he has been organizing Jim Ryun Running Camps as well as giving motivational seminars. Then in 1997 he successfully ran for the US House of Representatives, where he served for the next ten years.

Conclusions

It would be easy, though very wrong, to attribute Ryun’s groundbreaking performances to his undoubted natural ability. There is so much more to Jim Ryun. Clearly he was a great competitor; he performed well in almost all his important races up to 1969. And he was also a fine tactician, as Peter Snell has said. Then there is his capacity to undertake huge workloads over long periods. “Pain’s a natural part of being a runner…. You either deal with it or quit,” he told Jim Denison. (Bannister and Beyond, p. 95) Such a capacity for hard work confirms Ryun’s determination, dedication and courage. He was fortunate to have two fine coaches in Timmons and Edmiston, but he complemented their coaching with his undeniable intelligence.

Many look to the Olympic record for assessment of a runner. On the surface, Ryun appears to fail here. He was eliminated in the preliminaries in two of his Games, and was unable to win a gold in 1968. His first elimination was as an unwell 17-year-old; his second was caused by a fall beyond his control. Neither experience can be described as a failure on his part. And in his 1968 Olympics, although he was beaten handily by Keino, there is no doubt that he still ran a brilliant race for a non-altitude runner.

Jim Ryun was one of the great runners of the twentieth century. Up to 1969 his career was almost unblemished. It was only after his great run in Mexico City that he faltered. He had been training rigorously since he was 15. At 21 he was burned out mentally. In retrospect, he knows that he should have taken a break then. But in his Senior university year he had team obligations. He managed to keep going till the AAUs in June 1969. Then, as he put it, “the lid blew.” (Gold, p.104) After dropping out of the finals and out of running for a year, he never really recovered. He had some good races, but many others were huge disappointments. And he never improved on any of his PBs. Was he pushed too hard too early? There is no definitive answer. Certainly his hard work in his mid-teens produced world records and brilliant victories, but it is equally likely that the early punishing training regime shortened his career at the very top.

7 Comments