Bodo Tümmler Profile

b. December 8, 1943

|

In 1965 West German Bodo Tümmler burst dramatically on to the 1,500 European scene that had been dominated by Michel Jazy, Siegfried Valentin and Witold Baran. His European Cup victory and his fast 3:39.5 clocking at the age of 21 promised great things. The next year he won the European 1,500 title from 30-year-old Michel Jazy and placed a close third in the 800. Demonstrating not only great tactical skills but also strength and speed, the Berliner was being hailed as Europe’s Peter Snell. And although he was slowed somewhat by injuries the next year, his 1968 pre-Olympic form was impressive. And he did well in the high altitude of Mexico City, coming third in the 1,500 behind two great performers in Keino and Ryun. Sadly his career deteriorated after this as he battled with injuries. He never quite regained the form of his glory years between 1965 and 1968. But in those few years he was among the best in the world.

Early Days in Berlin

In 1965 West German Bodo Tümmler burst dramatically on to the 1,500 European scene that had been dominated by Michel Jazy, Siegfried Valentin and Witold Baran. His European Cup victory and his fast 3:39.5 clocking at the age of 21 promised great things. The next year he won the European 1,500 title from 30-year-old Michel Jazy and placed a close third in the 800. Demonstrating not only great tactical skills but also strength and speed, the Berliner was being hailed as Europe’s Peter Snell. And although he was slowed somewhat by injuries the next year, his 1968 pre-Olympic form was impressive. And he did well in the high altitude of Mexico City, coming third in the 1,500 behind two great performers in Keino and Ryun. Sadly his career deteriorated after this as he battled with injuries. He never quite regained the form of his glory years between 1965 and 1968. But in those few years he was among the best in the world.

Like many great middle-distance runners, Tümmler had an active youth. As a boy scout, he would join his Pathfinders club on Sundays, walking and running up to 25K. But he didn’t find sporting success in school: “I was too thin and too weak,” he once admitted. (“Bei den Pfadfindern die Ausdauer geholt,” 1965) The only sport that he had any success in was tennis. It was in fact while playing tennis that his interest in running began, for beside his regular tennis court was a stadium where runners trained. Intrigued by these runners, the 16-year-old asked if he could compete in a 600 trial. As a result of this run, he began to train in the stadium after his tennis and eventually he was talked into a Pentathlon competition. After four events, he ran the 1,000 in 2:48.

The next year, while still playing tennis, he ran 2:39.4 for 1,000 and 9:41.6 for 3,000. Then in 1962 he met Wolfgang Meller, who became his coach and focused him on a running career. Although he gave up his tennis, Tümmler was not pushed by Meller; instead he embarked on a long-term and systematic training regime. But results still came fast. That same year he ran the 1,500 under 4:00 for the first time with 3:58.4. He also improved his 1,000 time to 2:32.6 and ran 1:55.1 for 800.

Meller’s steady program brought promising results in 1963. Now 19, Tümmler began to compete at the top German level. He was seventh in the German indoor 1,500 and 10th in the ISTAF Berlin summer meet. He gradually improved his 1,500 time, running 3:55.6 and then 3:55.2 in May and then in August at the German championships he ran a heat in 3:49.4 and the final in 3:48.6, finishing sixth. This capped a wonderful year that saw him reach national level and reduce his PB by ten seconds.

First German Title

|

| Tümmler on the cover of Leichtathletik magazine in 1965. |

It wasn’t until 1964 that Tümmler began training 6-7 days a week. Although this was an Olympic year, Meller’s program did not focus on Olympic representation. The plan was still for steady progress. In May and June, Tümmler was running around 3:45 to 3:46, but not winning. Then he had a big win in an international meet in Cologne with a new PB of 3:43.6, beating two established runners in Hintzen and Norpoth. His competitive success continued with a North German title in 3:45.1 and then the German title in 3:42.7. This first national title in yet another PB was the highlight of his year, for in the German Olympic trials he finished back in seventh with 3:50.5. For the first time he appeared in the world rankings, his 3:42.7 earning him 36th position.

So what was the training formula that had taken Tümmler in his two years with Wolfgang Meller from a mediocre club runner to a national champion? Meller took the long-term approach and systematically built up his athlete’s strength and speed. He also adapted to Tümmler’s personality and let him train primarily in the forests away from the track: “I don’t do a lot of interval training; it’s too monotonous,” Tümmler said in a 1965 interview. ("Auf die Plätze,” Leichtathletik, May 11, 1965) So in the winter he was covering 10-20K of steady running, and in the summer five long runs with fartlek sprints. Of course, he did train on the track too, but mainly for learning pace judgment and what times he could aim for. As well, the competitive Berliner had found his event: “The 1,500 is my favorite event. It offers the most opportunities tactically.” (Sports Reporting Stuttgart) This gave more focus to his training.

The World Takes Notice

|

| Tümmler with his role modelPeter Snell. |

So Tümmler watched the Tokyo Olympics and saw his role model Peter Snell complete the double with 800 and 1,500 golds. Then he undertook another winter’s training with the expectation of moving into the international scene. Early in July of 1965 he was running for Germany with Harald Norpoth against two of the best 1,500 runners in the world: Bob Schul, Olympic 5,000 champion and Jim Grelle. The race was very close, with all four finishing within 1.7 seconds. Tümmler ran brilliantly, finishing second to Grelle in a PB 3:39.5. It was to be his fastest time of the year, but not his best result.

Two weeks later, he and Norpoth again teamed up, this time against Sweden. Tümmler was second again, this time losing to Norpoth 3:43.8 to 3:44.1. Tümmler turned the tables on Norpoth in the German championships, winning by just 0.2 from Norpoth in 3:45.6. Greater victories were to come. First he won the World Student Games 1,500 title from Green of England with a 3:46 clocking. There were reports of his jubilation at this win when 10m from the tape he waved to the Budapest crowd. But this win was nothing to compare with his fine victory in the European Cup 1,500 final. Running a 53-second last lap, Tümmler trounced two international stars for a significant victory: 1. Tümmler 3:47.4; 2. Wadoux, FRA 3:48.0; 3. May DDR 3:48.4. Overwhelmed after the race, Tümmler told the press, “At first I thought I was hallucinating.” (Ladislav Krnac, “Bodo Tümmler mit Taktik zum Sieg.” Leichtathletik, 1991) Journalists were now regularly comparing him with Peter Snell; Bob Phillips saw him as a potential winner in the 1966 Euros. He was now the fifth fastest in the world for 1,500 for 1965 and was showing great competitive ability.

European Champion

Tümmler started the 1966 season with a third-place finish behind Norpoth and Jürgen May. In top form by late June, he first ran a PB for 800 with a 1:47.1 victory in Berlin. Then just before an international against France, he helped pace Ron Clarke to his great 5,000 WR (13:16.6) in Stockholm. Tümmler took the Aussie through the first two Ks in 2:39 and 5:17 before dropping out after six laps. Four days later he was up against the great Michel Jazy, who would be a major challenger two months later in the Euros. Knowing that Jazy often relied on a late sprint, Tümmler showed confidence and courage by making his move at the bell and holding off the Frenchman to win with a 53.6 last lap. In one race Tümmler had shown he was the man to beat in the Euros in Budapest.

|

| With 100m to go, Tümmler (352) looks very relaxed atChris Carter's shoulder in the European 800. Outside him are John Boulter and Kemper. Winner Manfred Matuschewski can be seen behind Boulter. |

Still, by the time the Euros came round, the 29-year-old Jazy was in top form, having twice run 3:36.3, a European record. As well, Jurgen May and Alan Simpson were threats, not to mention Tümmler’s fellow German Norpoth. After a steady start (59.5), Norpoth took over at 600 and led with 2:03.4. He stayed in the lead, and Tümmler was right behind him at bell: 2:34.1/3:02.5. Jazy was close on their heels. Norpoth was still in the lead round the last curve. Tümmler then showed his speed, passing Norpoth for the win in 3:41.9. Behind him, Jazy only just managed to overtake Norpoth; both were timed in 3:42.4. Tümmler had run the last 300 in 38.8 and the last 400 in 52.7. In its race report, Track & Field News saw in him the “closest approach to Peter Snell Europe has produced.” (Sept., 1966)

One down, one to go: Tümmler was trying for a European double. Three days later he was lining up for the 800 final. The race was controlled by Chris Carter of the UK, who led through 200 in 25.4 and 51.8. Showing amazing strength, the Brit kept the lead until the last 40m. Coming into the final straight, he was still just holding off Tümmler. Right behind in lane 2 were John Boulter and Franz-Joseph Kemper. And also in lane 2, behind these two, was Manfred Matuschewski. Finally, with only 40m to go, Tümmler moved by Carter and must have thought he had the race won. But first Kemper passed him and then at the last moment Matuschewski came through a gap from fourth to hit the tape first. Result: 1. Matuschewski 1:45.9; 2. Kemper 1:46.0; 3. Tümmler 1:46.3; 4. Carter 1:46.3. Tümmler was only 0.4 away from a European double. All four had run PBs.

Tümmler raced a few more times in the 1966 season. After helping his team-mate Norpoth to a 2,000 WR, he had a fine victory over Witold Baran in a match against Poland (3:39.1 to 3:39.8). Then he helped another team-mate, Kemper, beat the 1,000 WR. He finished his season with a second place behind Norpoth in a match against Norway and a trial race in Mexico City where the Olympics were to be held at altitude in two years’ time.

Ryun Makes His Point

|

| Dusseldorf 1,500: Tümmler leads Harald Norpoth and Jim Ryun. |

As he went through another winter’s conditioning, Tümmler must have been feeling confident about his chances in the 1968 Olympics. After all he had been improving every year, and his competitive record was excellent. Everything had been going his way up to this point, but 1967 brought him down to earth. First he developed injury problems that left him below par for the track season. Second he was well and truly beaten by Jim Ryun in a match against the USA. It was a slow race. Norpoth and Tümmler were leading at the bell when Tümmler made his move. Norpoth was able to hold up Ryun a little round the back curve, but coming out of the curve, Ryun took off with such speed that he left the two Germans standing. The noisy home crowd was suddenly silent as it witnessed an incredible burst of speed from the American.

|

| Dusseldorf 1,500 Tümmler in full flight as Ryun roars by to a convincing win. |

Tümmler was emphatically beaten by 4.1 seconds by Ryun’s 300m burst (3:38.2 to 3:42.3) Ryun’s 50.6 last lap had made Tümmler look highly vulnerable to speed. It’s not known whether T’s injury had affected him in this race, but he had turned down a race in London just a week before, claiming he was unfit to run.

A month later he did run well in the European Cup Final, but the way he raced suggests that he wasn’t 100%. He was 20m behind the leaders at the bell but still managed to get up to second at the tape (3:40.5), finishing only a meter behind the winner Matuschewski (3:40.2). Still, this time was his best for 1967, ranking him 12th in the world. For the first time his improvement had stalled.

Olympic Build-up

Since he had passed up his chance to go to the 1964 Olympics, Mexico City loomed large on his horizon. His competitive season for 1968 began in June when he helped West Germany set a 4x800 relay WR of 7:14.6. A couple of low-key races over 1,000 and 3,000 followed before his first big race, a Mile in Stockholm on July 2. His main opponent was de Hertoghe of Belgium, who had run 3:39.3 in 1967. The Belgian gave Tümmler a good race as they went through in 57, 1:56 and 2:57. But Tümmler was the stronger and had a 1.3-second advantage at the tape. His 3:54.7 was a German record and the fastest of the year—faster than Ryun had run across the Atlantic.

Buoyed by this return to top form, Tümmler tackled the 1,500 in Cologne a week later. The pace was even faster than in the Stockholm Mile: 56.3, 1:56.5. Uncharacteristically, Tümmler took the lead just before the 800 mark. He was after Jazy’s 3:36.3 European record. He passed 1,200 in 2:55.5 and missed Jazy’s mark by a whisker with 3:36.5. Still, this time ranked him fifth fastest ever over 1,500. But his comment after this race suggested he was still dealing with injury problems: “I need to sharpen my speed in training. My kick is not as good as it was.” (Krnac, p. 21) It seems probable that Tümmler was already suffering from the achilles problems that led to operations on both legs at the end of the year.

But he was running faster times than ever. Two weeks after his great Cologne run he ran the fourth-fastest Mile ever in Karlskrona, Sweden with a 3:53.8. The Olympics were two months away, and after a 3:38.1 win from Gärderud over 1,500, he went to Mexico undefeated in 1968.

Racing at Altitude

|

| Mexico 1,500Keino leads at the bell.Tümmler, Norpoth, Whetton and Ryun follow. |

Having won his semi in 3:53.9, he lined up for the Olympic 1,500 final on October 12. He was in for a big surprise. Despite the altitude, Jipcho took the front at breakneck speed. Sensibly, Tümmler didn’t go out as fast as Norpoth, who was on Jipcho's heels on the first lap. Back in fifth after the start, he reacted to the fast pace after 200 when Keino decided to close the small gap that had opened up behind Jipcho and Norpoth. At 400 he was in fourth behind Keino as the field stretched out due to the fast pace. By 600 the first four had opened a gap on the field, with Tümmler looking comfortable in fourth. When Keino suddenly took over with two laps to go, Tümmler moved up to second—but not before Keino had opened up a small gap. The Kenyan had escaped.

Tümmler was not in contact as Keino went through 800 in 1:55.3, and down the back straight Keino lengthened his lead to 5-6m. Behind him Tümmler led Norpoth and Whetton. The rest of the field appeared out of the race. On the third lap Tümmler had to work hard to keep Keino within striking distance. He did this well, as the gap was only 7m at the bell. His team-mate Norpoth was still with him. Round the curve, Keino increased his lead slightly, while Ryun in fourth was making up a lot of ground on the two Germans. Soon after 1,200 (2:55.3 for Keino) Ryun challenged for second place down the back straight. Norpoth ceded, but Tümmler held him off (as he hadn’t been able to do the previous year in Dusseldorf) and kept second place until the crown of the bend. Then Ryun went ahead, winning the battle for second place. Keino, clearly tying up in the last 50m, nevertheless held on for a clear victory. Result: 1. Kipchoge Keino KEN 3:34.9; 2. Jim Ryun USA 3:37.8; 3. Bodo Tümmler WG 3:39.0; 4. Harald Norpoth WG 3:42.5.

|

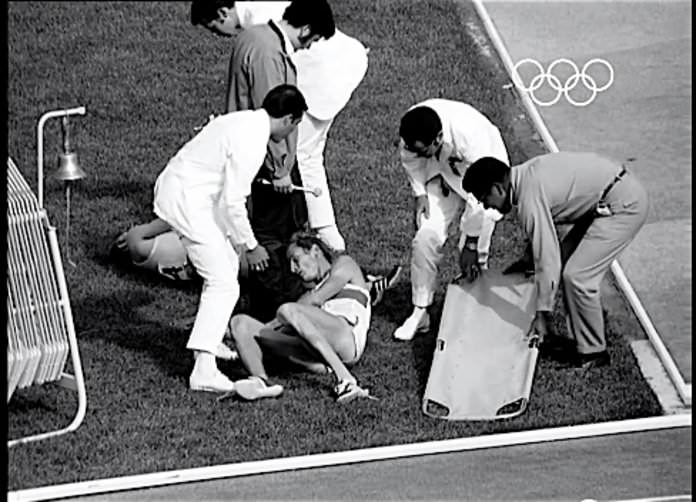

| Tümmler collapses after the Olympic race. |

Tümmler ran bravely in view of the altitude, and he showed great strength on the last lap, almost holding off Ryun. He had the distinction of being the only European to win a medal in the longer track events. “I have dreamed about running this race a hundred times,” he said afterwards. “I thought I could run 3:40 in Mexico, but in fact I ran 3:39.0. I’m very happy with that.” (Krnac, p. 21)

Coping with Injuries

After the Olympics Tümmler underwent operations on both his legs. And for a while it seemed that his injury problems were over. His 1969 season, which would hopefully include the Euros, started well with two good times over a Mile (3:58.8) and 1,500 (3:40.7). And he was also part of a team with Adams, Norpoth and May that set a German record for 4xMile with 16:09.6. However, he was well beaten in a match between Europe and the USA at the end of July. In this race Marty Liquori made his move early, just as Tümmler had often done himself. The American’s effort from 500 was matched by Arese of Italy and Tümmler. But round the last bend Tümmler was unable to stay with his two rivals. Liquori’s strength also broke Arese near the tape. Result: 1. Liquori 3:37.2; 2. Arese 3:37.6; 3. Tümmler 3:39.3.

This defeat suggested that Tümmler was not quite as fit as he had been in 1968, and Arese’s fine run meant the Italian was now the favorite for the Euro 1,500. The prospect of a showdown between the two of them at the Euros was nevertheless exciting. But politics got in the way. After defecting from East Germany, Jürgen May had been selected to run for West Germany. However, he had not satisfied residency requirements for West Germany. So he was not allowed to compete. This led to a mass walkout from the Euros by the West German team. Thus Tümmler was unable to run what was the main focus of his 1969 season. At least his 3:39.3 time kept him high (7th) in the world rankings.

To make matters worse, Tümmler developed injuries again. The whole of 1970 was a write-off. He was back competing in 1971 and managed to win his sixth German 1,500 title. But he was not in his best form and passed up the Euros: “Internationally I’m still not where I wanted to be,” he told Ladislav Krnac. “That’s why I’ll miss the Euros in Helsinki. The goal is Munich in 1972.” (p. 20) So with 1971 PBs of only 1:50.5 and 3:42.3, he went into his last winter of hard training.

Tümmler did make it to the Olympics. After some 1,500s in the low 3:40s, he won his seventh German 1,500 title in 3:41.5. This qualified him for Munich. He managed to get through the first round of the heats, but he was last in his semi with a 3:50 clocking. It was a sad ending to a great international career.

Conclusion

Tümmler’s career has left us with many “what-ifs.” What if he had managed to recover fully from his injuries? What if the 1968 Olympics had not been held at altitude? What if West Germany hadn’t boycotted the 1969 Euros? What if he had been fully fit for the 1972 Munich Olympics and had competed with Keino and Vassala? Clearly Tümmler had the potential for even greater things. Still, he did achieve a lot in the few years he was fully fit. He will be remembered for his wins in the 1965 European Cup and the 1966 Euros, but his greatest race, surely, was his third place in the 1968 Olympic 1,500. Although more interested in competition than in records, he nevertheless posted some fine times: 3:53.8 for the Mile, 3:36.5 for 1,500 and 1:46.3 for 800.

1 Comment