Peltzer v Lowe: Great Races #26

880 AAA British Championships, July 3, 1926

|

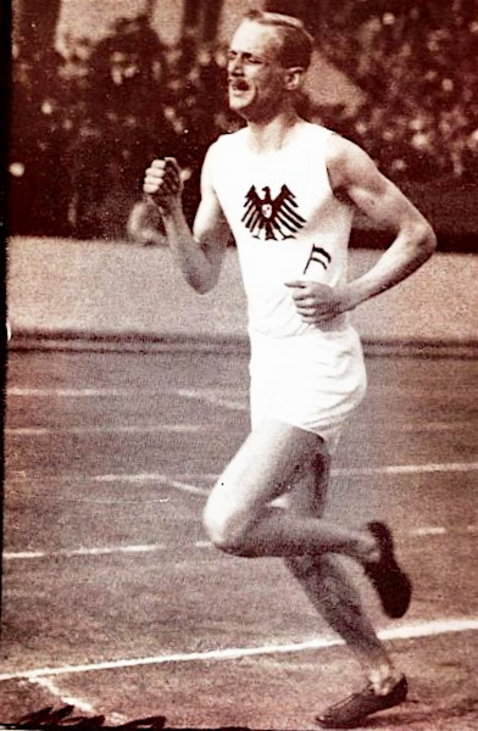

| Otto Peltzer, the first German to compete in Britain after World War 1. |

With the First World War only eight years in the past, it was quite a talking point when German 800 runner Otto Peltzer entered the 1926 British Championships. Germany had not been invited to compete in the Paris 1924 Olympics, but clearly the British authorities, two years later, were more forgiving. And there was added interest in the fact that Douglas Lowe, the 1924 Olympic champion for 800, would also be competing. Peltzer, as 1924 German champion over 800 and 1,500 would have competed in Paris had Germany been invited, so he clearly had something to prove. It was Britain against Germany again, but this time on the Stamford Bridge running track rather than on the battlefields of Europe.

Expectations

The 35,000 London crowd fully expected to see its Olympic star achieve another victory over Germany. Douglas Lowe, a university graduate destined for the legal profession, had established himself as the best 880 runner in the world and was still improving. Not only did he have great physical talent, but he was also a fine tactician. He won his races. Perhaps he did not have the 440 speed of Peltzer, but he compensated for that with his tactical skills.

Peltzer was the emerging track athlete of Europe. He had appeared on the international scene in 1923, running 1:54.7 and 3:59.4 for 800 and 1,500. Over the next two years he focused more on the 400 and 800, lowering his PBs to 48.8 and 1:52.8 (only 0.9 of a second off the world record). It was these two events that he entered for the AAA Championships in 1926. That meant four races in two days, a tough assignment even for someone as fit as Otto Peltzer.

Of course there were other competitors apart from Peltzer and Lowe. Wilfred Tatham, the British 440 Hurdles champion in 1924, qualified for the final and was to be the pacemaker. And although he represented Britain in the 800 in the 1928 Olympics, he was not considered at this time to be a potential winner. CR Griffiths was the runner most likely to challenge the two stars. He had won the 880 title the previous year.

After heats on the previous day, the 880 final pitted one German against five Britons. And as Quercetani has written, “In the eyes of international critics, [Peltzer] hardly had a chance against Lowe.” (Track & Field News, July 1950) Lowe’s tactics had been carefully thought out. Although he was a noted finisher himself, he was aware of Peltzer’s faster 400 time. Thus Lowe had to develop a tactic that would nullify Peltzer’s sprint advantage in a tight race. While he could have stayed with his regular proven tactic of following and winning in the final straight, he decided that he had to make the pace so fast that Peltzer would either not be able to stay with him or would have nothing left in the last straight.

An interesting incident took place just before the start of this much anticipated race. Peltzer, on approaching the start line, was informed by an official that he could not start the race because his running shorts were too brief. While the other competitors waited, he was forced to return to the dressing room to find a more modest pair of shorts. Predictably unable to find a suitable replacement, he put his shorts on back to front, pulled them down a little lower and returned to the start. The starter was satisfied with the change. (Anecdote from Edward Sears, Running Through the Ages)

The Race

|

| Otto Peltzer finishes well clear of Lowe. |

The varsity runner (Eton and Cambridge) Wilfred Tatham took out the early pace, likely at the request of Achilles team-mate Douglas Lowe. Lowe took second position right behind Tatham, with Peltzer on his heels. Tatham wasn’t quite fast enough for all of the first lap, so Lowe had to take over at the front. He passed the bell in 54.6, well under WR speed. Peltzer and Griffiths were still with him. They stayed in the same order until the back straight, when Peltzer made a move to pass Lowe.

Peltzer repeatedly challenged the Englishman all down the back straight, only giving up as they entered the last bend. Dropping back to run close to the curb, Peltzer looked for a moment as though he was losing contact. But he still had a lot left and was waiting until the final straight. But the German didn’t find it easy to catch Lowe; for almost half the last stretch the Englishman held off Peltzer. Then between 60 and 40 yards from the tape they ran side by side until Peltzer’s strength was too much for Lowe, who began to tie up.

Peltzer hit the tape in a new WR of 1:51.6 (former record 1:52.2 by Ted Meredith in 1915). As well, Peltzer’s 880 time was faster than Meredith’s 800 record (1:51.9 in 1912). (There were no watches arranged for an 800 time.) Douglas Lowe, whose brave pace had made the WR possible, may well have also broken the WR as he was only three yards back. But, according to The Times, “Unfortunately, the timekeepers were too overwhelmed by the occasion to take his time.” (July 25, 1926) Griffiths in third place must also have been disappointed that no time was taken for him. Only six yards behind Lowe, he must have run a PB around 1:53.

Although Lowe had run his fastest 880 ever, he nevertheless came in for some criticism. The critics said he went too early. But Harold Abrahams defended Lowe, saying that he had used the best tactics in the face of Peltzer’s finishing speed. (Quercetani, T&FN, July 1950) And from today’s perspective it’s hard to criticize a runner who has run faster than ever before. Lowe, impressed by Peltzer’s speed, subsequently changed his training, improved his 440 time to 48.8, and went on to win the Olympic 800 for a second time in 1928.

Not long after his world-record run of 1:51.6, Peltzer placed a close second in the 440 final, just losing out to JWJ Rinkel in 49.9. Thus in the two days of the AAA Championships, he ran five races. In the first-day heats he ran 50.6, 50.0 and 2:00.4; in the second-day finals he ran 1:51.6 and 49.9. The 35,000 spectators gave him an ovation; residual animosity from the world war was temporarily erased by a brilliant athletic performance.

Leave a Comment