Book Review

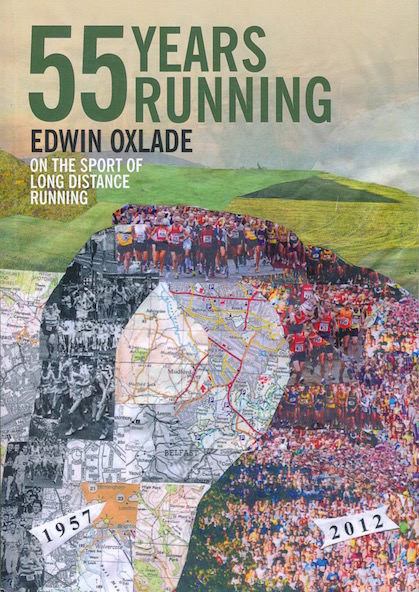

55 Years Running by Edwin Oxlade

2013, 396pp

|

There must be lots of people in the British running community who know the name Edwin Oxlade. Not that he was a top-level runner. In fact, he was a good club runner with times of 49:52 for 10 Miles, 1:05:57 for a half Marathon and 2:24:24 for a Marathon. For a long time he was deeply involved with the UK club scene, and he has now decided to put all his memories and opinions into print. “ I like to think of the book as a personal view of the history of running, in particular British distance running, during the course of my lifetime,” he explains in his short preface. “Personal” is a key word here because Edwin Oxlade has a lot of opinions--and I don’t mean this in a negative way.

55 Years Running is also personal in that for the first part he uses his own running career to structure the book. As he moves through his 55 years of running, there are many digressions into different aspects of the sport. Training of course is a major topic, and he bases his views on his own experience. Thus there are such chapter headings as ”Six Rules of Training,” “Training Myself,” “Hard or What?” He also tackles the World Cross-Country Championships, racing, sex and drugs, and lastly ageing.

Oxlade writes well and is always interesting. I believe this book would be of interest to anyone who was involved in the British club scene in the last 60 years. He writes about many of the top runners like Ian Thompson, Fergus Murray, Ian Stewart….. The list would be very long. But he also writes from the perspective of a club runner, saying for example, quite rightly, that most of those who line up in a club race have no thought of winning because they know they are not good enough. This point is rarely made in print and shows that there is a lot of original thought in Oxlade’s book.

He’s also good on how training evolved: “Of far greater significance than the type of training, however, was the quantity. Before the 1970s the running world was still very much in the midst of a process of discovery and learning as far as amounts of training were concerned. ‘Big’ trainers tended to be very much in the minority and were probably seen, despite the obvious success of some of them, as mere crackpots. Worse, they were seen by some as setting a dangerous example. That much hard running was surely not good for anyone.” (61)

I’ll give a couple more examples of the topics he covers. He focuses on some elite runners over the decades. Here is what he concludes about Roger Matthews: “What makes the example of Roger Matthews iconic, more so than even his contemporary and more famous 200-miles-a-week runner Dave Bedford, is that he was, or had been, in the words of the well-known coach Frank Horwill, ‘a mediocre athlete.’”

Oxlade also has some interesting things to say about the success of university runners in the 1960s: “One doesn’t have to look any further…for an explanation of why universities produced such good runners in the numbers that they did. Any system that takes young people nearing the peak of their physical abilities, puts them into a shared environment, looks after their immediate needs, encourages them to achieve their objectives, manufactures a competitive structure and team spirit, and gives them plenty of free time, is bound to produce excellence. It only takes one or two single-minded individuals with drive and ambition to start and steer the process, and the enthusiasm and commitment they generate spreads through the group.” (81

There is a lot of good down-to-earth advice too: “I learned from bitter experience that marathons cannot be run with the heart and body alone. The head is also involved. Less than ten seconds a mile too quick—that’s no more than 3 percent—is all it takes to turn potential success into disaster. Never mind how easy it feels, if it’s too fast on paper, it’s too fast.” (241)

I am not always in full agreement with him. For example, he argues in favour of the front-running tactic of Viren and Farah in the Olympics. Both of them won races from the front by taking the lead with more than a lap to go and holding off any challenges. Oxlade’s main point is that all those jockeying behind Viren and Farah had to run extra distance as they were rarely able to hug the curve like leaders Viren and Farah were able to do. He has a point and might also have added that with this tactic Viren and Farah lost no energy in jockeying for position and changing pace. But Oxlade omits to mention drafting. According to tests, running in the front of a race costs just over one second per lap or about 7 meters. The issue is surely more complex than Oxlade’s single point. But his argument is interesting and typical of the way he will often question orthodox beliefs.

55 Years Running is a long book full of material that should interest anyone who has been involved in the British running scene. I highly recommend it, and I’m going to send copies to a couple of my “old” running friends. Well run, Edwin!!

Copies of 55 Years Running can be ordered direct from Edwin Oxlade ([email protected]) The cost is 13 pounds sterling plus 3 pounds postage for the UK.

Leave a Comment