John Landy Profile

b. 1930

The second man to break the four-minute-mile barrier, Australian John Landy is universally respected as one of the great runners of the twentieth century. His dignity, sportsmanship and courage are beyond dispute. However, he will always be seen as the one who could have—could have run the first four-minute mile and could have won Olympic and Empire titles.

Born into a prosperous family in 1930, Landy went to the prestigious Geelong Grammar School and then studied agriculture at Melbourne University. Like most Australians, he was sports-minded, originally trying to succeed in Australian–rules football. He also ran to keep fit for football. When he made the state athletics team in 1951, he decided to take the sport more seriously. After winning the Combined Schools Mile in a modest 4:43, he was introduced to Percy Cerutty, the colourful local coach. This meeting changed Landy’s life; he gave up football and started to train seriously as a runner.

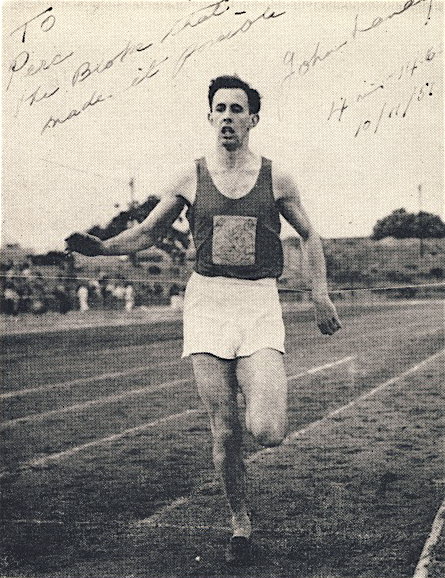

|

| Landy's dedication to Cerutty: "The bloke that made it possible." |

His progress under Cerutty was remarkable. Within three weeks he ran 4:31 and after four months it was 4:17. A few months later, Cerutty described Landy in a letter: “As a runner this fellow is amazing. Courage and desire to excel without undue display of effort, much less suffering, causes him to run well within himself, as he admits…. He has legs like an ostrich with terrific muscular definition and size for his weight and bulk. He moves over the ground in just the same effortless manner and is amazing to watch.” (Sims, Why Die?, p.104)

With confidence from such early success, Landy was able to tolerate the abrasiveness of Cerutty. When his time improved to 4:11 and he was hailed as Australia’s biggest prospect, Landy was quick to credit Cerutty: “Without his guidance and inspiration I couldn’t even have approached the times I ran last season.” (WD?, p.110) With his rapid improvement, Landy was just good enough to make the Australian team for the Helsinki Olympics, although he was a contentious choice.

In London before the Games, Landy met Bannister for the first time and ran a new PB of 4:10. However, he ran miserably in his 1,500 Olympic heat, finishing fifth in a poor 4:14. In a post-race assessment, he concluded that Cerutty had been of little help for this race. Still, Landy didn’t waste his time in Europe, learning a lot about the sport from other runners, especially Emil Zatopek. He found that Cerutty’s ideas didn’t always make sense. Above all, he realized how much better European running shoes were.

Returning home long before his coach, Landy began to use the ideas about interval training and running style that he had absorbed in Europe. “I trained like the dickens for three months,” he later told Jim Denison. (Bannister and Beyond, p.20) Soon he was running 4:08 miles in training and finding that his European shoes were really helping. In the first race of the 1952-3 season (December 13), an inter-club, he made an amazing breakthrough with 4:02.1, running the last three laps on his own. It was the third fastest mile ever. In a post-race interview, Landy was still willing to credit Cerutty, saying that “Most of the credit must go to Perce.” (Sims, Why Die?, p.143) But Cerutty, when he heard the time, went ballistic, saying that if he could now run that fast now, he had let the side down in the Olympics. Soon after, Landy broke with Cerutty.

Now the hunt was on for the four-minute mile. He made two more attempts that season on January 3 and 24: 4:02.8 and 4:04.2. Each time he raced, here was a huge expectation that he would beat four minutes. Still there was a lot working against him: the pressure of high expectations, unfavorable weather and the absence of good competition.

Perhaps Landy should have gone to Europe in 1953, but he was in his final year of studies. Still in May 1953 he began training for the next Australian season. With his finals done, he started with a 4:09 and then in December he ran 4:02.0, passing the bell in 3:00.2. On January 21, 1954, he tried again: 4:02.4. Then twice in February: 4:05.6 and 4:02.6, then another 4:05 and 4:02 in March and April.

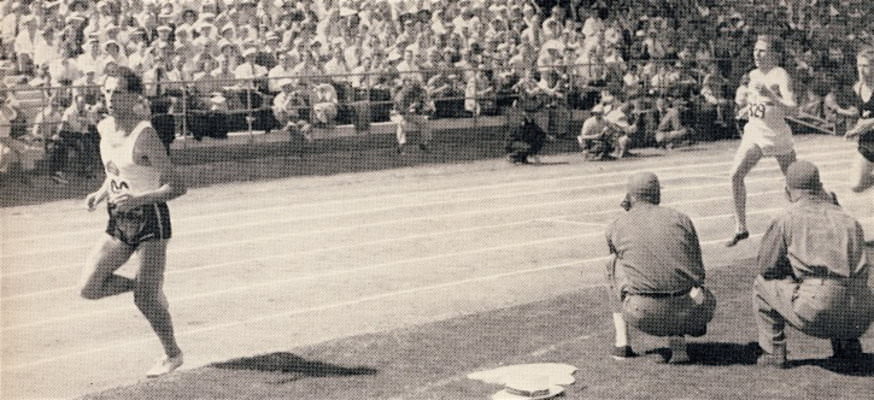

|

| Pushed by Chataway, Landy finally breaks 4:00 and the world record. |

At the end of the Australian season, Landy set out for Europe—only to hear in Finland that Bannister had finally beaten four minutes with 3:59.4. In all his fast races in Australia, Landy had lacked any competition to push him to fast times. He had run under 4:06 nine times since the 1952 Olympics. Now in Helsinki on June 22, 1954, he finally had some real competition: Chris Chataway who had towed Bannister from 2 1/2 to 3 1/2 laps in the first four-minute-mile race. Chataway was confident he could beat Landy. After four warm-up races, two of which he had run in 4:01.6 (his best ever), Landy was ready. His speed was impressive, as time-trials over 200, 300 and 400 had shown: 23.0, 37.0, 49.0.

Landy followed a Finn through 440 at 58.5 and took the lead at 660. He passed 880 in 1:57.9, with Chataway 3m back. Landy ploughed on, trying to keep the pace even. He was surprised that Chataway was with him at 1320 (2:56). Keeping the same tempo, Landy rounded the bend and then took off. Chataway had no reply. Landy passed 1,500 in 3:41.8, a WR, and then held on for a fabulous 3:58.0 Mile WR. In the right conditions and with Chataway to push him, Landy had finally done it.

Now he had to get ready for Bannister. The Empire Games in Vancouver in July were not far away. Landy tuned up with an impressive 1000 in 2:20.9, only a second off the WR. The story of his valiant attempt to break Bannister with a fast pace is told in Great Races # 9. Bannister was indeed his nemesis—beating him to the four-minute mile by 46 days and then decisively defeating him in the final man-to-man race in Vancouver. Landy ran a valiant race, at one point having a 10m lead over Bannister. But the English runner managed to catch him by the bell and unleashed an unanswerable sprint in the last 220.

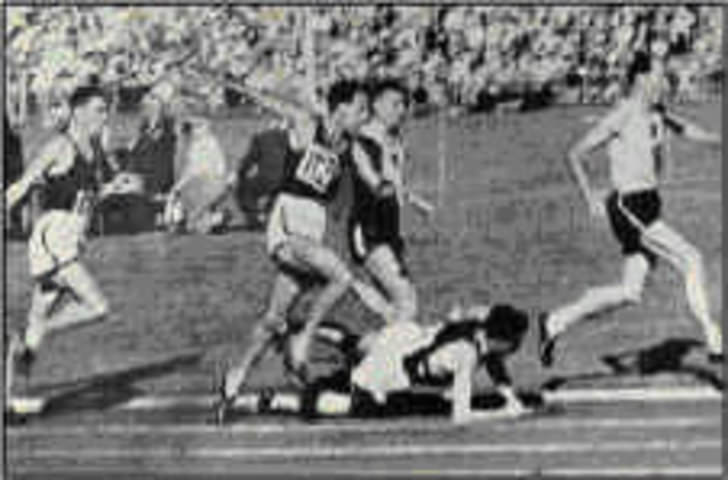

|

| Front running was his only option. Landy tries to breakBannister in Vancouver. |

Landy paid the price of being a front runner by nature. In his career in remote Australia, he had had little opportunity to hone his competitive skills, just as he had never been pushed by another runner in any of his Australian attempts to beat 4:00. It’s easy to sympathize with his resigned comment after his defeat by Bannister: “I don’t have the temperament of a race winner. I just like to run fast.” (Johnson, “Landy Recalls,” The Age, June, 21,2004)

Landy said he would have retired on the spot if he had won in Vancouver. He nevertheless continued competing as the next Olympics was to be on his doorstep in Melbourne. A start was made in a remote area of Victoria, where he took a teaching post. This area had no track, so he ran over rough ground to get basic conditioning. He now preferred his own training and turned down a coaching offer from Franz Stampfl. When the new 1955-6 track season opened, he went to Melbourne for competition, believing he was not really ready for fast times. So he was amazed when he ran a 1:51 time-trial. He still had track speed, and he confirmed it with two sub-4 miles, both in 3:58.6.

|

| Landy stopped in the Olympic trials after his accidental tripping of Ron Clarke.(Albie Thomas photo) |

All of a sudden, Landy looked like a great Olympic prospect. In the Olympic trials he amazed everyone by winning after stopping to help a young runner, Ron Clarke, whom he had accidentally tripped and spiked. Landy lost about seven seconds, yet still ran 4:04.2. This incident became a legend in Australian sport, not only for the gallant gesture but also for the amazing time he ran.

But Landy’s Olympic preparation was damaged by an American tour he was persuaded to make to promote Melbourne’s Olympics. He ran two sub-4s, but the hard American tracks damaged his achilles tendon. He continued to train but his heel didn’t improve. He tried to race in spikes in early October and had to stop. By the end of that month he said that he was fit to run in the Games but that he was not expecting to be 100%.

|

| 1956 Olympic 1,500 final: Landy (156) was the fastest finisher, but he left his effort too late |

In the 1,500 Olympic final, he started slowly, so when the race exploded in the third lap he was forced to run very wide down the back straight. But then he pulled back, unsure that he had the strength to go that early. There was a huge bunch ahead of him coming into the final straight, yet Landy, the front runner, had enough speed to clinch third. People said he left his sprint too late. “I thought I had no chance at all before the race,” he said afterwards. “Only in the last straight did I begin to hope.” (Olympic Saga, p.107)

Bannister, reporting for Sports Illustrated, wrote: “I believe Landy could have won this race. But he ran as though he knew he could not win.” Bannister concluded with a tribute: “For Landy this was probably the end of the greatest solo mile-running career the world has seen and of an athlete faster, neater and more generous than any other.” (SI, 7 Jan 1957)

Soon after, Landy retired. He subsequently had a distinguished career as Governor of Victoria. As a naturalist he has written a seminal book and has worked for the environment on the Land Conservation Council of Victoria. With two WRs and six sub-4s, Landy was undoubtedly one of the great runners of the 1950s.

14 Comments