Kerry O’Brien Profile

b. 17 April 1946 1.80 68kg

|

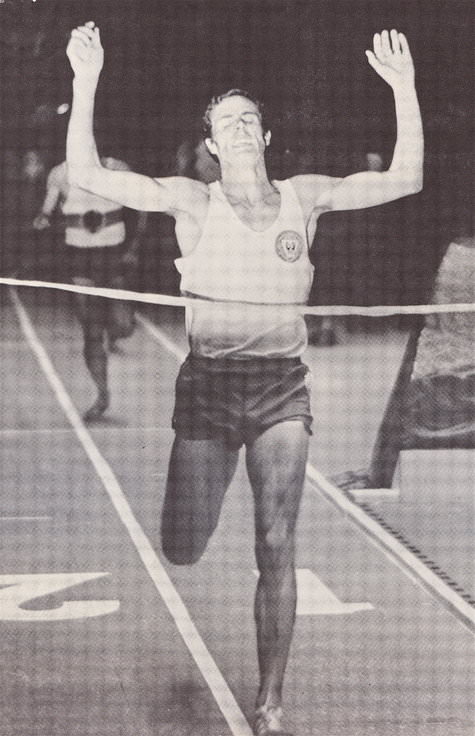

| Kerry O'Brien sets an indoor world record for Two Miles with 8:19.6. |

“Slow down! Slow down!” This can often be good advice—but surely not when you’re a champion runner like Kerry O’Brien. Yet the South Australian world-record-holder has continually been told to slow down for most of his life. It’s nothing to do with his running; it’s his personality. “I’m an A-type triple plus,” he admits. “My life’s a constant go.”

Of course, an A-type personality is a double edged sword. It can lead to overwork, stress and even breakdown. But with intelligence and self-discipline it can enable great achievements. Kerry O’Brien made good use of his A-type personality to break world records for the 3,000 Steeplechase and the Indoor Two Miles, win nine Australian titles, earn a Commonwealth silver medal, and place fourth in the 1968 Olympic Steeplechase final.

O’Brien’s story is inspiring, showing how hard work and a willingness to learn led to a period of three years (1969-1971) when he was close to unbeatable. There were also setbacks that needed great determination to overcome. Sadly the last setback, a freak injury, caused his competitive career to end prematurely. He was forced to retire while he was still improving.

-- ---------------

Kerry O’Brien was born a small town called Quorn, 330K north of Adelaide in South Australia. Like most Australian youngsters, he had an active childhood: “I lived near a railway siding. We were outdoors from morning to dark —very active. I did a lot of endurance work without knowing it.” He enjoyed sports at school—football, cricket, tennis. “From a very early age, O’Brien recalls, “I was running simply for fitness—to better myself in those sports. And then a harriers club formed in Port Augusta, where I [later] lived.” When he won a Pepsi Footathon three-mile race, he began to focus on running.

His interest was further stimulated by his father who brought home running books like Herb Elliott’s The Golden Mile, and Peter Snell’s No Bugles, No Drums. Elliott especially inspired him, and he became so interested in Elliott’s coach, Percy Cerutty, that he began to train with him: “I used to travel to Portsea as a young kid. I was only 15. I’d earn my keep by cutting tea trees and sweeping paths. It was a Spartan existence running up sandhills.”

Move to Melbourne

His visits to Cerutty’s camp at Portsea, a 2,000K round trip, continued from 1961 to 1963. A second place in the Australian Junior championships (4:16.1) indicated progress. Then, while working as an apprentice electrical fitter in Port Augusta, O’Brien decided he needed to be able to train with other serious runners. So in 1965 he moved his electrician indenture to Melbourne so that he could train with the likes of Ron Clarke, Trevor Vincent and John Coyle. This was a big move for him: “It was very difficult for me living away from home—no structure, no car. I lived in a boarding house with a landlady who thought I was an absolute idiot. She wouldn’t keep my meals hot. So I came in after training to a cold meal—sausages and eggs in solidified fat. It was very difficult, but I did get to run with the guys. On a Sunday we would run up into the hills.”

He soon made an impact on the Australian running scene. In December of 1965, he ran his first Steeplechase in an impressive 8:55.5 . After the New Year, he improved to 8:46.0 and then won the Australian title with 9:01.8. That season he also ran 1,500 in 3:48.6, Two Miles in 8:42.4, Three Miles in 13:30.6 and 5,000 in 14:13.0.

First Commonwealth Games

His national title qualified him for the 1966 Commonwealth Games in Jamaica later in 1966. As a warm-up for the Games, he competed in Los Angeles for Australia against Great Britain, the USA and New Zealand. His fourth place behind winner Traynor of the USA in 9:06.4 was barely respectable and gave no indication of the breakthrough to come.

Predictably it was hot and humid in Jamaica for the Commonwealth Games Steeplechase final. This would have suited O’Brien, who was used to the heat of South Australia. His main opponents were Maurice Herriott, who had won an Olympic silver two years earlier with 8:32.4, the talented Kiwi Peter Welsh, who had run 8:41.4, and Kenyan Benjamin Kogo, whose PB was 8:47.4.

O’Brien’s PB of 8:46 looked outclassed by Herriott’s 8:32, but he had a reasonable chance of a silver medal ahead of Welsh and Kogo. From the start Welsh ensured that the race would be fast by leading the first three laps a little below 8:30 speed. Then a second Kenyan, Chirchir, took over. The race continued at a quick pace with no one making a move until two laps to go. It was O’Brien who made a decisive move from ten yards back to take the lead. Herriott was the first to react. As O’Brien and Herriott approached the bell, Welsh moved up to join them. The order of the first three changed on the back straight as Welsh passed Herriott on first of the two hurdles and drew level with O’Brien. Welsh’s superior hurdling technique told on the second hurdle and he led into the water jump by a couple of yards. O’Brien couldn’t match Welsh’s sprint and was 20 yards down by the finish. But he did hold on to second place. His 8:32.4 was a PB by 13.6 seconds. This was another huge improvement for the 20-year-old, who had run his first Steeplechase in 8:55 only eight months earlier. Was he surprised at this huge breakthrough? “No, I knew I was running the times and was doing the work.” Result: 1. Peter Welsh NZL 8:29.6; 2. Kerry O’Brien AUS 8:32.4; 3. Benjamin Kogo KEN 8:33.0; 4. Maurice Herriott 8:33.2.

After this amazing race, O’Brien still had two more events in the Jamaica games. In the Three Miles, held two days after the Steeplechase, He was unable to finish. But after another three days he qualified for the Mile final with 4:09.84 and then ran a PB 4:02.72 in the final for 8th place.

Home and Abroad

|

| Lining up for an indoor race: O'Brien with Prefontaine (left) and Puttemans. |

O’Brien returned to Australia with a Commonwealth silver medal and a 14.4 improvement in his Steeplechase time. And in his first steeple of the 1966-67 season (three months later) he improved again to 8:29.0. With his newly attained world-class status--ranked fourth in the world for 1966--he was soon off for the American indoor season. “I loved indoor racing,” he recalls. “I took to it like a duck to water.” Between January 26 and February 4 he ran four races, winning three times over Two Miles (8:39.6, 8:38.3, 8:46.6) and finishing second in a Mile (4:06.4). His first race was in the famous Madison Square Gardens and his winning Two-Miles time was a track record there. He was awarded a Wanamaker Trophy that still stands in his Adelaide home today.

In each of the following years, O’Brien toured the USA during their indoor season. To protect his full-time job, he compressed these tours into just over a week: “I enjoyed it but never wasted any time. I was never a great burden to my employer.”

After his first USA tour, he went straight to New Zealand to race the man who had beaten him in Jamaica, Peter Welsh. This time he was victorious in 8:38.8. His season finished in March with his second Australian title in 8:39.9.

Olympics Ahead

For the 1967-1968 competitive season he followed the same schedule: early races in Adelaide, a January-February tour of American indoor meets, a race in New Zealand on the way home and finally the Australian championships. His early-season times were not as fast as the previous year: 8:45.8 and 8:49.0 for the steeplechase and 14:10 for 5,000. And in the USA after winning his first Two Miles race in 8:49.0 from Kurt Kvalheim, he was hammered in his next Two Miles by fellow Australian Kerry Pearce, who set a WR of 8:27.2 on the fast San Diego track. O’Brien was 14 seconds behind in 8:41.2. In his last indoor race he was up against a stellar field: George Young and Tracy Smith of the USA and fellow Australians Ron Clarke and Kerry Pearce. Running a much better race, O’Brien was with the leaders to the end as George Young finished just ahead in 8:31.8. He was third in the same time as second-place Tracy Smith with 8:32.6 PB. Ron Clarke was fifth in 8:35.0.

Back in Australia he beat Peter Welsh again with an 8:46.4 Steeplechase. Then despite running a 7:52 PB, he lost to American Tracy Smith over 3,000, although he did beat Clarke. He had a really bad race in the Australian Championships, finishing third behind Welsh and Manning in 9:00.2, but he came back four days later to win a Steeplechase in 8:40.6 ahead of Manning.

His season had not been too successful. Whereas each previous season had shown huge improvements, this 1967-68 season had seen no progress in his steeplechase, and only a small improvement in the 5,000 (4.4 seconds). This did not augur too well for the Olympics as he began his winter’s training for Mexico.

Olympic Build-up

While northern hemisphere athletes were fine-tuning in European races, O’Brien stayed home for the pre-Olympic months and ran only two low-key steeplechases, both in 8:41.0, both victories. But he was training really hard, fully aware of the challenges he would face in the Mexico City altitude: “I punished myself pretty violently on a hill in North Adelaide. I pushed myself into oblivion because I knew what was coming.”

As it turned out, O’Brien was the only Olympic finalist who wasn’t altitude trained. “I saw people collapsing on training runs in Mexico City,” he recalls. “It was a really tough environment for distance running. I was lucky I adapted very well for an athlete from sea level. George Young [another finalist] had six months’ training in the Colorado mountains with the US Marines. I was the only sea-level athlete to make the final.”

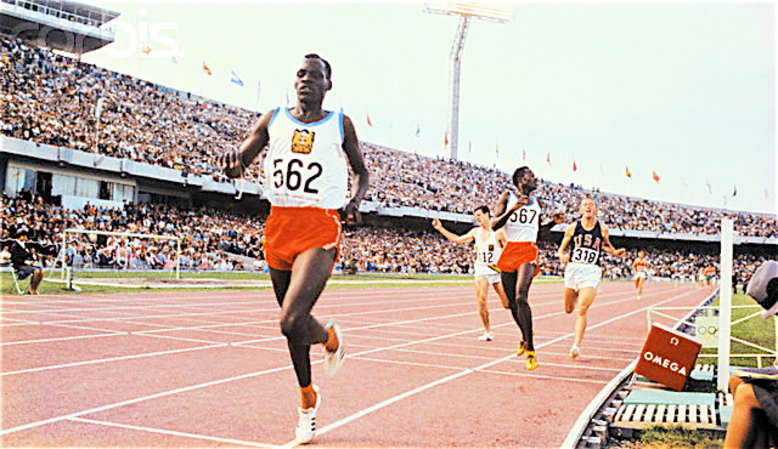

|

| Finish of the 1968 Olympic Steeplechase final. From left to right: Biwott,O'Brien, Kogo, Young. |

After qualifying comfortably in 9:02.31, he started the final conservatively, staying in the pack despite a slow first K (3:04.2). In the front the two uninhibited Kenyans, Biwott and Kogo, were varying the pace. O’Brien was sixth at 1,000 and fifth at 2,000 behind the leader Roelants (6:03.2) Then he began to lose contact with the lead group. With two laps to go he was not quite up with three leaders, Roelants, Kogo and Young. Although back in fifth place, he was still “in striking distance” (Track & Field News, Oct./Nov., 1968).

At the bell he was up to fourth just behind Roelants, who had fallen back from the two leaders. Soon past Roelants, he bore down on the two leaders, and on the back straight, when Young made his move to the front, O’Brien went with him past Kogo and into second. Behind the leading trio, Biwott was making up a lot of ground having initially appeared to be out of contention. The last water jump favoured the two Kenyans: Kogo went into the lead and Biwott closed the gap in front of him. Kogo led at the last hurdle with O’Brien and Young neck-and-neck behind and Biwott just behind them. Biwott showed amazing speed in the last 60m and passed all three to win in 8:51.0 from Kogo.

In the final run-in, it looked for a moment like O’Brien was going to catch Young, but some 20m from the finish he tied up, and the American held on to third. Later, O’Brien told Pat Putnam of Sports Illustrated that after the race he was “so upset” that he had been beaten by someone with “a terrible technique”—Biwott. Nevertheless, it was a fine run for a non-altitude runner. Robert Parienté, the distinguished French journalist, has written that O’Brien would surely have beaten the Kenyans had the race been run at sea level. Nevertheless, his fourth place put him ahead of some great steeplechasers: Morozov, Zhelev, and Roelants. Result: 1. Amos Biwott KEN 8:51.02; 2. Benjamin Kogo KEN 8:51.56; 3. George Young USA 8:51.86; 4. Kerry O’Brien AUS 8:52.08.

Post Mexico

With his reputation even higher than after his Commonwealth silver, it was practical for O’Brien to join the European circuit in 1969. But first there was the Australian 1968-69 season, which started right after the Olympics. His initial race, a very fast 8:31.0 Steeplechase, preceded of a string of wins over 1,500, 3,000 and 5,000. Before his regular USA trip he was beaten only once, over 1,500 by C. Fisher. His US tour had three races over Two Miles. He started with a win in Seattle (8:40.3). Next he ran his fastest time in Portland to beat rival Kerry Pearce in 8:34.9. But he could not beat George Young in his last race, finishing second in 8:43.0.

Back home, he finished off his Australian season with three races in the national championships. He won the Steeplechase comfortably enough, his 8:39.8 giving him a 13.8 cushion over second place. But in the 5,000 and 10,000 he came up against Ron Clarke, who beat him into second in both races with margins of 10.0 and 37.4. O’Brien’s times were 13:54.2 and 29:21.0.

First European Tour

Two months later he began his 1969 European tour with a 10,000 in London. Although he beat his PB by 37.4 seconds, he could finish only sixth, as Dick Taylor led a stellar distance field with a British record of 28:06.8. It was a harsh introduction to the European circuit. Overall, his schedule was 11 races in 22 days. He won three of his four Steeplechases, losing only to Zhelev of the USSR. His best race was in Stockholm, where he won in 8:31.4. His flat races were not remarkable; his best run was a 5,000 in 13:48.0, where he was fifth.

On his way home, he competed in two races at the USA v Commonwealth v USSR meet in Los Angeles. In the 5,000 he placed fourth out of six in 14:25, and then in the Steeplechase he ran a brilliant PB of 8:26.8, finishing a close second to Russian Morozov (8:26.0). It was a great ending to his first world tour.

Australian Season

Two weeks later he was winning the Australian cross-country title in Brisbane. There was a short break after this, before he was off to Tokyo for the Pacific Conference Games. There he won the 3,000 Steeplechase (8:35.4) in a tight race with fellow Australian Tony Manning. A month later the Australian track season began. He showed he was still in top form when he ran a solo 8:31.6 Steeplechase in the middle of November.

O’Brien maintained peak form through the New Year, running another fast 8:32.0 Steeplechase at the end of February and beating Ron Clarke over 5,000 (13:37.2) just before the national championships. He defeated Clarke again over 5,000 in those championships, but Manning won the race in 13:56.6 to O’Brien’s 13:57.4. He was perhaps a little tired for this race as he had won the Steeplechase title the day before in 8:34.4.

World Steeplechase Record

|

| Berlin 1970. On his way to a world record. |

Ten weeks later, his 1970 world tour began with a few races in the USA and then some European competition before the Commonwealth Games in Edinburgh. It was to be his most successful tour with 17 victories in 20 races. He began well with three victories in the USA: a 5,000 in 13:42.2, a Three Miles in 13:10.8 (beating Clarke yet again) and an 8:41.2 Two Miles (ahead of Gerry Lindgren). In Europe he won all of his eight races before the Commonwealth Games. He started with three victories over 2,000, 3,000 and 5,000 in Scandinavia before tackling his first Steeplechase in Stockholm. In this race he won in 8:29.4, not far off his 8:26.8 PB in 1969.

Two days later in the Berlin ISTAF meet, he did much better, shattering his PB and breaking the world record with 8:21.98. The previous record (8:22.2) was held by Vladimir Dudine of the USSR. O’Brien’s record was to stand for two years. As he remembers, “There was competition around, but it was not a super strong field. I had lap times planned, and Pam Kilborn [great Aussie hurdler] read them out for me. I ran even paced; I was programmed to run fast.” In fact O’Brien led the whole way. His three K’s were indeed very evenly paced: 2:46.8, 2:49.0 and 2:46.2 for an average of 2:47.3. The second-place finisher, Rolf Burscheld of West Germany finished almost 10 seconds back in 8:31.8.

Edinburgh Fall

O’Brien was the odds-on favorite to take the Commonwealth Steeplechase gold. And in the penultimate lap it looked like he had the race sewn up when he moved into the lead just before the last water jump. Then disaster struck: his leading leg hit the water-jump hurdle and he fell full length and face-down into the water. He was out of the race and out of the medals. With the Commonwealth Games two weeks ahead, he had hit top form at just the right time. In those two weeks he won a 5,000 ahead of Clarke in 13:52.2. Then he ran the Commonwealth 10,000 before his main event, finishing 8th in a PB 28:43.49.

The only good thing about the accident was that he was not hurt badly and was able to continue his European tour. He had six more races in Europe. They included two Steeplechase wins in Stockholm and Oslo (8:29.2 and 8:31.2). In fact, he won all of his races but the final one, a 3,000 in Cologne. There was a stellar field for this race: Norpoth, Wadoux, Shorter, Falke, and Puttemans. Against this formidable opposition O’Brien (7:50.8) did well to finish second behind Norpoth (7:49.6) and ahead of Puttemans (7:51.8). Except for the Edinburgh catastrophe, his tour had been a huge success. It had established him as the world’s premier steeplechaser. And his prospects for further improvement seemed excellent.

Another World Record

After a three-month break from competition, he gradually worked himself into top form. By the beginning of 1971 he was able to run a fast 3,000 (7:50.4) and a Three Miles (13:12.8) before heading off to the USA for his regular whirlwind indoor tour. His first race saw him losing over Two Miles to Kerry Pearce. Still, his time was good (8:30.8), and he was still acclimatizing. A week later he raced Pearce again on the fast San Diego boards. This time he was flying and left Pearce well behind.

|

| O'Brien follows Kerry Pearce en route to hisindoor Two Miles world record. Frank Shorteris on the right. |

The Two-Miles field also included George Young and Frank Shorter. A Californian miler, Ron Pettigrew, was the assigned rabbit. He took the field through the first mile at a fast but steady pace: 62.3, 2:06.0 and 4:11.9. Pearce took over for a lap, before O’Brien himself went into the lead. His fierce pace drew Pearce with him but left the two Americans far behind. Pearce moved back into the lead again and held it to the bell, when O’Brien went ahead for good and finished in a world indoor record of 8:19.2. This astonishing time improved Pearce’s indoor world record by 8 seconds and was even faster than Ron Clarke’s outdoor world record of 8:19.6.

His USA tour continued in Vancouver, Canada, (3,000 in 7:58.0) before he returned home for the Australian championships. He had a really fast steeplechase before that meet, clocking 8:24.0 and winning by 28 seconds. After this fine run, he easily won two national titles: 3,000 Steeplechase in 8:54.0 and 5,000 in 13:44.2. Then, showing impressive speed he defeated Dick Quax and Jim Ryun over Two Miles (8:25.6) in New Zealand. Clearly he was running faster than ever, and with some good competition in Europe to come, he was expecting to improve his PBs, especially since he was “bursting through track work better that I had done the year before when I had run the WR.”

“I’d Have Run 8:15 Without a Doubt”

But this was not to be. He was running along a sidewalk with a group of six training partners when he accidentally stepped off the 12-inch curb at the edge. He remembers, “Everyone heard this rip and wondered what it was, including me. I went on to run twenty repetition quarter miles, but the next morning I couldn’t lift my leg out of bed. I never recovered from that. It wrecked my career; it finished me. If I’d just got to Europe, I’d have run 8:15 without a doubt.”

After eight months’ recuperation from the resulting groin injury, O’Brien returned to competition on January 15, 1972 with a slow win over 5,000 (14:20.4). Next he went to North America for his indoor tour. He started off in Toronto this time, winning a Three Miles in 13:23.8. Then he raced twice over Two Miles in California, finishing third behind Prefontaine and Puttemans (8:39.8) and third again behind Puttemans and Kardong (8:39.0).

Back in Australia he ran three Steeplechases in preparation for the National championships and for selection for the Munich Olympics (8:42.6, 8:34.0, 8:30.8). As usual there was no one to challenge him for the national title as he won by a 16.8 margin in 8:31.2. Eleven weeks later he began his European season on June 15, just 2 1/2 months before the Olympics.

But all was not well. Following principles establish by Percy Cerutty, O’Brien had trained long and hard to develop upper-body and abdominal strength: “This was to strengthen the lower back and abdomen so that, as he put it, you could run over the ground not through it. The Percy Cerutty theory made me one of the heaviest distance runners in the world having developed my upper body.” This extra weight made it even more imperative that O’Brien should run lightly over the ground. However he was now unable to do so as effectively as he had done before. “After the injury I couldn’t use my stomach muscles properly to keep my weight lifted up from the ground,” he explains. “So I was hitting with a heavier footfall, and the result was many overuse-syndrome injuries. I shouldn’t have even been in Munich with my injuries.”

Munich 1972

Despite this problem he had to soldier on. His pre-Olympic races were a mixture of 5,000s (3) and Steeplechases (5)—plus a 2,000 and a 3,000. The 5,000s were encouraging; he won two and was second to Viren in the third: 13:43.6, 13:54.5 and 13:39.8. His first Steeplechase in late June was a fast 8:27.0. Surprisingly it was the only steeplechase he won. Subsequently. he lost to Zhelev (8:25.6), to Kantanen and Garderud (8:30.2), to Smitkowski and Kondzior (8:29.0) and Koyama (8:35.4). This was unusual, for in his two previous European tours, he had lost only one Steeplechase—to Zhelev.

So he no longer had an aura of invincibility when he came to the Munich Olympics. As it turned out, O’Brien didn’t even make the Olympic final because he fell in his qualifying heat and was unable to finish. According to Athletics Weekly, he “smacked into the barrier” on the back straight of the last lap after one of his shoes “flew off.” (September, 9, 1972) Another fall, another medal lost. Judging by the times of the medalists (8:23.6, 8:24.6, 8:24.8), O’Brien could surely have been in the medals. It was small recompense that contrary to general expectations, his world record survived the Olympic final.

Last European Tour

After a long break, O’Brien returned to competition to win his seventh and last Australian Steeplechase title (8:41.0). Then he embarked on his final tour abroad. After winning the Steeplechase in the Pacific Conference Games in Toronto (8:36.6), he raced just six times in Europe. There were no victories, although in his first and only European Steeplechase he ran a fast 8:26.40. However, this fast time earned him only fifth place behind Jipcho, Garderud, Kantanen and Mogaka. His other races were respectable, but he was not running as well as he had previously done in Europe—a couple of 3,000s around 8:00 and a couple of 5,000s in the high 13:40s. In his very last race he was a disappointing ninth in a Two Miles in Stockholm with a time of 8:45.99.

Retirement

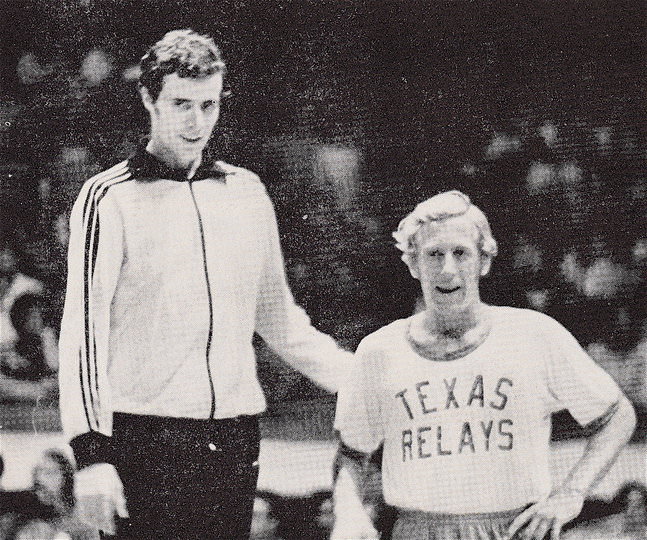

|

| Celebrating a victory with Kerry Pearce. |

So the 26-year-old O’Brien retired. It was not just that his groin injury was still affecting his performances. There was another more serious problem—a heart problem. In a race in Stockholm, he ran into oxygen debt early: “I knew it wasn’t right,” he explains, “so I went to a specialist hospital which dealt with a lot of athletes. They said it could be the pollen count, but I’d never had pollen problems. In those days there was a lot of suspicion about blood doping.” O’Brien told them he had never blood-doped. Finally the doctor told him that he had an inverted t-wave, adding “If you go and run in Helsinki in two days as you say you will, don’t blame me if you drop dead on the track.”

This had a strong effect on O’Brien: “It frightened me, so I retired. Also, I was an old crock [with my injury] and couldn’t run properly.” Later, back in Australia he talked to sports doctors who told him that he had already been diagnosed with an inverted t-wave in Mexico in 1968. As he was currently running at a world-class level, they thought it was normal.

Retirement from top-level sport always comes with regrets, and O’Brien had his fair share. His freak groin injury was a piece of bad luck. His heart may not have been a problem, since he had previously set world records. But the seed of doubt had been sown and would always be there if he had continued to train and race hard.

Retrospect

Still, he could look back on his career with pride and satisfaction. In his glory years from 1968 to 1971 he achieved much. His fourth place in the Mexico Olympics and his two world records were his greatest achievements. His ability to perform well in big meets has not always been recognized because of his two unfortunate falls in the 1970 Commonwealth Games and in the 1972 Olympics. But he ran beyond expectations in the 1966 Commonwealth Games and in the 1968 Olympics. As well he captured ten national titles and won gold in the 1969 Pacific Conference Games.

He chose to specialize in the Steeplechase because of his innate limitations. Although he was quick—“I had reasonable speed, enough to beat Dick Quax of New Zealand in 1971.”—he didn’t have the finish to win big races on the flat: “I was marginally faster than Ron [Clarke] but vulnerable to the big kickers.” Without a reliable finishing kick he had to run from the front: “Ron Clarke and I had to surge and push from the front, set the pace and hopefully drop off these guys who could sit on you and bang you.” And more often than not he did “drop off” his opponents.

Post-Competition

After his running career, O’Brien gave up his job as an electrician to work for Coca-Cola as a marketing executive. Since 2006 he has been running a large fitness centre in Adelaide.

8 Comments