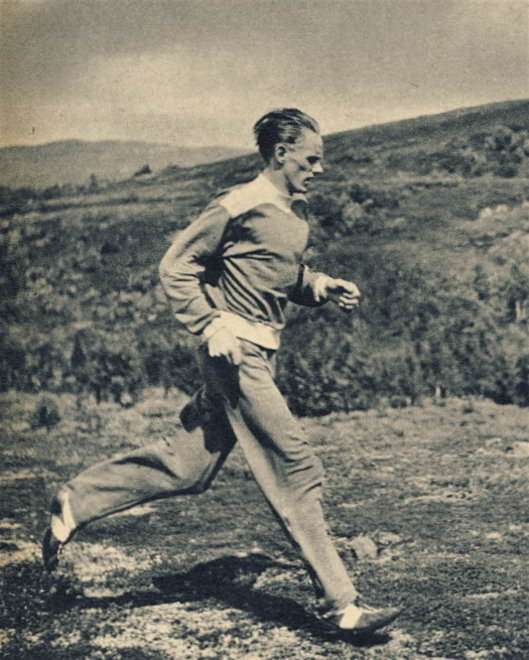

Gunder Hägg Profile

1918-2004

|

| Hägg leads. Arne Andersson is close behind. |

This great Swedish runner set fifteen WRs between 1941 and 1945. He improved the Mile WR by 5.0 seconds, the 1,500 WR by 4.8 seconds, the 3,000 WR by 7.8 seconds and the 5,000 WR by 10.6 seconds. As well as a record-breaker, Gunder Hägg was also a fierce competitor; his tactic of burning off all competition from the front worked almost perfectly until his penultimate competitive year (1944), when his great rival Arne Andersson beat him in five out of six races. Had not World War Two prevented Olympic and European Championships during his career, Hägg would surely have won several medals. After years of heavy physical work and then a consistent winter conditioning schedule of running and cross-country skiing, he developed into an almost perfect runner. A Times reporter noted “the smooth beauty of [his] stride which was mechanical only in the sense that perfect motion is mechanical.” (Aug.7, 1945)

Early Development

Gunder Hägg’s boyhood activities provided a good base for his subsequent running career. Growing up as a country boy in the remote mountainous Jämtland area of Sweden, he began cross-country skiing at the age of six. In the summers he worked in the forests, helping with his father’s woodcutting business. He quit school early to work with his father and quickly developed the physical strength to do a grown man’s job. As well as body-core strength he developed stamina from the long workdays and the distances he had to travel by foot and by ski.

Apparently he started competitive running after discovering how well he could run in the snow without skis. As a 12-year-old he had already shown athletic promise by winning a 10K ski race. His interest in competitive running had been stimulated by the success of a local Jämtland runner, Henry Jönsson-Kalarne , who won an Olympic 5,000 bronze in 1936 and set a WR for 3,000. Then there was the encouragement from his father. An anecdote that Hägg wrote up later tells how his father, Nils Henrik, paced out a 750m course in the forest and then timed his teenage son over 1,500. Wanting to encourage him, he cut 30 seconds from the time Gunder actually ran.

At age 16 in 1935 Hägg ran 4:54 to win a local 1,500, but at this time he was also sprinting, pole vaulting and high jumping. The next year he won two Junior Jämtland titles with 4:22.2 and 16:11 in the 1,500 and 5,000. Late in the season he greatly improved his 1,500 time to 4:14.

Getting Serious

Hägg’s talent was soon noticed—by the man who had encouraged and initially coached Jönsson-Kalarne . Fridolf Westman, a farmer, offered Hägg a job on his farm and accommodation in the very room that Jönsson-Kalarne had used. In May of 1937, with his father’s blessing, Hägg moved in. That summer he improved his 1,500 PB to 4:13 and then in a 2,000 race he was able to defeat Gunnar Höckert, the 1936 Olympic 5,000 champ, with a time of 5:39.6. Hägg later called this his “breakthrough race.” (Top Distance Runners of the Century, ed. Seppo Luhtala, p.110.) Following this win he raced in Stockholm for the first time, placing fourth in a 3,000 with 8:36.8. Finally, representing Jamtland, he ran second in a 1,500 with a new PB of 4:08.9.

Westman was careful not to train Hägg too hard over the winter over the 1937-1938 winter. And his 1938 competitive season was satisfactory without showing great improvement. After beating his PB by one second over 1,500 (4:07.9), he ran a Two Miles in 9:16.6 and then tried the 3,000 Steeplechase, clocking 9:28 and then 9:23. Finally in September he tried the 5,000 again, this time recording 15:00.7. It appeared that he hadn’t yet decided that the 1,500 was his best event.

Hägg trained more seriously in the winter of 1938-9. From January 1939 he lists a five-times-a-week schedule that emphasized stamina: two long walks (10K), two non-stop runs for one hour, and one long walk of 30-50K. He lists his longest walk as 54K. On May 1 he stopped the walking sessions and replaced them with interval sessions (omväxlande gång = varying running) and 20K runs.

Unfortunately Hägg missed the whole 1939 competitive season after developing a lung infection. It was a major setback, but he was not discouraged.

Hard, Serious Training

|

By the end of 1939, his health had improved enough for him to carry out his military service. He was posted to Norbotten in the north of Sweden, where troops were protecting Sweden’s valuable ore deposits that were threatened after Russia invaded neighbouring Finland.

Over the winter of 1939-1940, Hägg became really serious about his training and ignored the commonplace wisdom of those times not to “overtrain”: “I was training so hard that I really had only two ways to go: to break down or to run faster than anyone else before.” (Luhtala, p.110) Because of his location near the Arctic Circle, he did much of his running in the deep snow. Sometimes it was too cold to train.

From December 18 he would run either in deep snow or along a cleared road. Sometimes he would do both snow-running and road-running in one session with 2,500 meters of each. Other times he would run 4,000m in deep snow for a session or do a hard 5,000 run. Once or twice a week he would cross-country ski for 15-40K, often as part of his military training. From the middle of April he stopped snow-running and did either hard or easy 5K runs.

From today’s perspective, Hägg’s mileage was very low. However, it’s important to appreciate the hard work involved in running in deep snow. As with sand-dune running, it takes very little time to reach exhaustion when running in knee- or hip-deep snow.

1940 Season

With the war between Finland and the USSR over, Hägg was allowed to go abroad for competition. He even competed in Helsinki. He began his season with a 1,500 PB of 3:59.6—8.2 seconds better than his 1938 mark. With two winters of conditioning behind him since he last competed, he had now improved so much that he was competing on equal terms with Sweden’s top two runners. In his second 1,500 race he beat both his hero Jönsson-Kalarne and Åke Jansson,a 3:49.2 runner, with a stunning 3:51.8 PB. He was brought back to reality in a 2,000 where he was pushed into fourth (5:19.2) by Jansson, Arne Andersson and Jönsson-Kalarne. But he responded with a 3,000 victory in an 8:18.2 PB.

If he wasn’t world class already, he certainly was after two races in August—but he lost them both to Jönsson-Kalarne. The first race was a 1,500 in Gothenburg against all three runners who had beaten him in the earlier 2,000. Jansson led for the first lap, and then Hägg led through 800 in 2:01 and 1,200 in 3:05. Jönsson-Kalarne, in third, made his move with 200 to go, passing Andersson and then moving up to Hägg. The two fought it out right to the tape, with the more experienced Jönsson-Kalarne winning by just 0.1 of a second. As a result of this thrilling battle, Jönsson-Kalarne equaled the national record of 3:48.7, and Hägg clocked a wonderful 3:48.8 PB for second.

A week later Jönsson-Kalarne again beat Hägg, this time over 3,000. But Jönsson-Kalarne had to run a WR to beat the young pretender. His 8:09.0 was 5.8 seconds faster than Gunnar Hökert’s previous mark. Hägg was also well under the old WR with 8:11.8.

Both runners were in Helsinki in early September for a 5,000. This time Hägg was the winner with 14:38.2, another PB. Two days later in Stockholm, the in-form Hägg raced Jansson over 1,500. In this race Jansson was able to avenge his early season defeat by Hägg. But only just, as both runners clocked an impressive 3:49.0. Hägg ran another fast 1,500 in 3:52.4 at the end of September, beating Andersson into second. His three month competitive season had seen great improvement over his 1938 times: 19.1 seconds for 1,500 and 25 seconds for 3,000. Just as important was the emergence of Hägg’s competitive ability. Although he won only about half of his races, he was still extremely competitive in the races he lost. His losing margins were all small: 1.6, 0.1, 2.8, 0.2, and 0.2 seconds.

Vålådalen 1940-1941

When his military duties were completed at the end of 1940, Hägg returned to Jämtland. But this time he moved into Gosta Olander’s resort at Vålådalen. He spent almost five months there from December till the end of April, working as a handyman and training six days a week.

Although Olander was never Hägg’s official coach, there is little doubt that he had a lot of influence on Hägg’s training. The two Jämtlanders had a lot in common, especially their love of the outdoors and their belief that training should be done in natural surroundings. Olander may well have had some input into Hägg’s sessions, especially his session that combined deep-snow running and road running. Initially Hägg did 2,500m of each, but then changed to 3,000/2000. He would do the deep-snow running first on a special course he had devised in the birch forests. After the hard part, he was able to run fast and free along the cleared road back to his hut.

From December 8 to April 20, Hägg did this session on 84 days. He also did cross-country skiing on twelve days, either fast (6-10K) or steady (10-17K). Of course there were rest days too: 27 that included a 4- and a 2-day break.

By the time he left Vålådalen to take a job as a fireman in Gävle, Hägg felt he was stronger than before. He also paid tribute to the “positive and comfortable atmosphere” that Olander created at Vålådalen: “And when everything is counted, that atmosphere is more important [than the trails around Vålådalen] for an athlete in training.” (“Possibly Better Condition Than Anyone Anytime,” Vålådalen, ed. Gunvald Håkonson, p.56) Not surprisingly, in the following years, Hägg would return to Vålådalen regularly for short visits.

1941 Season

|

| En route to his first world record:1,500 in 3:47.6. Arne Andersson and Arne Ahlsén follow. Note how relaxed Hägg is compared to the other two. |

The five months with Olander helped turn Hägg into a more polished runner and a world-record holder. He was now a better competitor with better speed. This was evident both in his unbeaten record for 1941 and in his 1,500 WR. Possibly under the advice of Olander, Hägg focused on the 1,500 for the 1941 season. Of the 17 recorded races for 1941, twelve were over 1,500 and two over the Mile. It is interesting that for one of his early-season races, Hägg traveled with Jönsson-Kalarne to wartime Germany for a 3,000 race in Berlin. Hägg won in 8:19.2, with Jönsson-Kalarne finishing third.

Hägg rounded into form by the end of June, running 3:51.4, 3:49.8 and 3:50.2. In the latter race, an international race against Hungary, he was pushed by Andersson, who finished only 0.2 of a second behind. Three days after this race in Malmö, Hägg equaled the European record with 3:48.6. He was closing in on Lovelock’s five-year-old WR of 3:47.8. He beat it just three weeks later at the Swedish Championships in Stockholm. Again pitted against Andersson, Hägg led from the gun. Andersson stayed close through laps of 58.8, 63.2, and 61.5, but he was 7m behind as Hägg broke the tape in a new WR of 3:47.6. Hägg’s strength enabled him to hold off the fast-finishing Andersson with a 44.1 last 300.

The rivalry with Andersson was now established. At this point, Hägg was always the winner, though often by very little. The two had one more race in 1941 in a Mile held in Gävle, where Hägg was now working as a fireman. Hägg again won in the fast time of 4:09.2. It was indeed fortunate for Hägg during these world-war years that there was someone in his own country who was good enough to push him to world-class times. In fact, the rivalry would push both runners to new heights in the next three years.

But in the meantime, Hägg was suspended for nine months for accepting money from race promoters. Amateurism had long been a problem in track because top runners could draw huge crowds and were thus offered money to compete. “The stadia were full for my sake, weren’t they?” argued Hägg later. “After all, I never asked for money; they offered it. So I took it. Would I have run if I hadn’t been offered money? Of course not.” (Track & Field News, 22 Sept. 1974)

Training for 1942

The nine-month suspension hardly affected Hägg, as it coincided with the winter and spring. He spent the time training hard so that the very day the suspension was lifted, he was ready to run a world record.

Hägg’s training over the winter of 1941-1942 was done mainly in Gävle, where there was relatively little snow. Thus the combination of deep snow running and tempo running that he had employed over the two previous winters was not possible. Still, he did manage 12 deep-snow sessions in December and a few in February during visits to Vålådalen. He was also able to put in 12 deep-snow sessions from February 25 to March 19. Overall, he did 26 deep-snow sessions compared with 84 the previous winter. Otherwise, in his short meal-break sessions (often in only 20 minutes), he trained on a racetrack adjacent to the firehall where he worked. Sometimes he did fartlek, sometimes steady runs.

In June he switched to twice-a-day training. In the morning he did mainly easy runs of 5-6K, while in the afternoons he focused on fast runs in the forest over 3-6K. For the last two weeks of June he was again at Vålådalen with Gösta Olander. In these two weeks almost all his afternoon running was fast (snabb).

1942 Season Part 1

|

| July 1, 1942. Mile world-record race in Gothenburg. Hägg: "We have just turned into the final straight and Arne is gearing up to pass me." |

In Gothenburg on July 1, the day he was reinstated, Hägg participated with Andersson in a carefully planned attack on Sydney Wooderson’s 4:06.4 Mile WR. Olle Petersson led the field through 400 in 58.8, and then Gösta Jacobsson took over for a 62.2 second lap (2:01). Petersson did some more leading in the third lap, but then Hägg, challenged by Andersson, went to the front and passed 1200 in 3:05.8, with Andersson still right on his heels. In the last 300 Hägg had to fight hard all the way to the tape to hold off Andersson. His hard-won and narrow victory produced a new WR of 4:06.2, Andersson clocking 4:06.4. Thus the rivalry that had begun in 1941 was heating up even more. Hägg’s tactic against Andersson was always the same: run hard enough to negate Andersson’s lethal kick.

He beat Andersson again two days later in setting a Two Miles WR with 8:47.8. After running 4:27.0 for the first mile, he sped up on the second mile with 4:20.8. In the next two weeks, Hägg ran six races; only one of them was significant, a 3:48.4 1,500. Then, on July 17 in Stockholm, he captured the treasured 1,500 WR. After being taken through 400 in a brisk 57.2, he was soon in the lead, passing 800 in 1:58.2 and 1200 in 2:58.9 (almost six seconds faster than in his Mile WR). With this faster pace, Andersson could not stay with him. Not surprisingly, Hägg slowed in the last 300 (46.9) but was still able to lower his record by 1.8 seconds to 3:45.8. He had bravely pushed the pace in the middle of the race and broken Andersson, who finished 3.4 seconds behind. Hägg’s victory in this race remains one of the greatest examples of front running.

|

| The end of the Gothenburg Mile. Hägg hasheld off Andersson's challenge to run a4:06.2 world record. |

World Record number four came just four days later in Malmo, this time in the 2,000. He lowered American Archie San Romani’s record by just 0.4 with 5:16.4. His season so far, with four world records, must have seemed like a dream to him. But reality suddenly confronted him: he became ill. After two low-key races, he returned to his base in Gävle to tackle the 3,000 WR of 8:09.0 held by Jönsson-Kalarne . The meeting was Gefle IF’s Autumn Games. Hägg was fêted beforehand, receiving a homage address in a ceremony in which some 3,000 inhabitants made donations for a statue of Hägg to be erected in Gävle. This Olof Ahlberg statue was erected five years later in 1947 and still stands outside the Strömvallen Stadium.

In front of a record home crowd of 9,333, Hägg just missed the 8:09.0 WR with 8:09.4. A recent blog entry by an eyewitness at this Gävle race 71 years ago captures the high expectations around Hägg at this time: “It is Sven Rohlén, Hägg’s manager at the Fire Department…. He reads from the results list, ‘Unfortunately, there is no world record. Gunder Hägg won in the world’s best time this year, with 8:09.4.’ There is silence in Strömvallen. A disappointed silence. The expectations were so high. ‘There was no applause from the stands,’ writes Gunder Hägg himself. ‘Had I been healthy the world record would have gone.’” (The Shy One, March, 23, 2007. www.lotten.se)

Four days later in Vasteras, clearly not 100%, he was unable to anchor his club to a 4x1,500 Relay win, clocking only 3:55.8 and losing out in the final stretch to Lennart Nilsson. Gunder Hägg was physically run down and ill. “I’m not burned out, but I’m sick,” he wrote in his diary. (www.lotten.se) He probably should not have run his last two races, but there had been a lot of pressure on him to satisfy first his Gävle fans and then his relay partners. In 33 days he had run four WRs and won 15 races. It was time for a break. Despite the clamour of race directors, Hägg sensibly decided to take a three-week break at Vålådalen.

1942 Season Part 2

Three weeks later, following rest and a gradual return to full training, Hägg was ready to compete again. He started with a race close to Vålådalen in Östersund. Again Andersson was there to push him and again Hägg broke a WR. This time it was the 2,000 WR he had set just a month earlier; he knocked an impressive 4.6 seconds off his previous mark with 5:11.8. There was clearly something wrong with Andersson at this point in the season, for he finished nearly 19 seconds behind. Hägg’s new 2,000 record would stand until 1948. Clearly refreshed from his break, he attacked the 3,000 WR in Stockholm five days later and knocked a massive 7.8 seconds off Jönsson-Kalarne ’s record. Not since Kohelmainen’s 8:36.8 in 1912 had the 3,000 been lowered by such a large margin.

|

| Hägg pushes the pace before a huge crowdin the Stockholm stadium. Andersson ishanging on. |

World Record #7 came just a week later at an international meet in Stockholm. This time it was the mile, and there was no Andersson to push him. Hägg was to attack his own 4:06.2 WR. But after poor pacemaking—a suicidal 56 first lap, with Hägg a second back—it looked like the opportunity was lost. So he focused on winning the race and forgot the record attempt, passing 800 in 2:00.2 and 1200 in 3:04.2. As he went into the last lap he began to hear the crowd urging him on. Accelerating, Hägg passed 1,500 in 3:48.8 and knocked 1.6 off of his own WR with 4:04.6. Among the spectators was the German Rudolf Harbig, who said of Hägg after the race, “He is fantastic. One [had to] have seen him in this race to believe his unbelievable times. His form is perfect—smooth and flawless all the way through the race.” (The Milers, p.145)

Hägg now focused on the longer distances and broke three more WRs, numbers eight, nine and ten. First he broke the Three Miles WR with 13:35.4, and then he improved this mark in a 5,000, passing three miles in 13:32.4 and finishing in 13:58.2 to become the first man ever to beat 14:00. He had improved the 5,000 WR by 10.4 seconds; the previous record had been Finn Taisto Mäki’s at 14:08.8.

Hägg’s last seven races in 1942 were low-key, but he maintained his unbeaten record. His fastest of these races was a 3:50.6 in an international meet in Hungary, then an ally of Nazi Germany. Andersson, still competing, was beaten again (3:53.2). It had been a glorious season and there seemed no reason why 1943 could be even better for the 24-year-old. But a decision he made in early 1943 set back his career considerably.

American Tour

In early 1943 Hägg was invited to tour the USA in the summer. He was to be a “quasi-official Swedish ambassador” with the aim of raising money for the US Army Air Forces Aid Society. Using Swedish neutrality, Hägg had already competed in Berlin (1941 and 1942) and Budapest (1942); now he was to visit the “other side,” even dropping in at London (and going for a run in Hyde Park!), before setting off to aid the war effort in the USA. His political motives for accepting the American offer have never been clarified. If he was personally supporting the allies—and this may well be the case as his cultural roots were close to Norway, which had been brutally invaded by Germany—why did he agree to run in Berlin and Budapest? These trips were surely a tacit gesture of support for the Third Reich. Another motive for his USA trip might have been financial, but he was making good money running in Sweden, and he claimed that the only payments he received in the USA were “expenses, plus $1 a day to enjoy myself.” (NY Times, 1987). Then of course there was the glamour of America. His posing in a cowboy outfit indicates how appealing the American way of life was for Europeans.

As for his running career, surely it would have been better to stay in Sweden where the competition, especially with Andersson, was good. Crossing the Atlantic in wartime 1943 was a much tougher prospect than today’s six-hour plane trip. So although in many way he was a success as an ambassador and as a competitor in the USA, his trip definitely had a negative effect on his running career because his next (1944) Swedish season, despite three world records, was a lot less successful than his 1942 season.

|

| Hägg wins his first USA race after a tiringtransatlantic trip. |

To get to the USA, Hägg spent 25 days at sea on the Swedish merchant steamer Saturnus. It was great that the ship had security guarantees from the warring sides, but it offered no running facilities except a 70m corridor that he could only use when the ocean was calm. Needless to say, Hägg was not in good running shape when he landed at New Orleans. He had two weeks to prepare for his first race, a 5,000 in New York against Greg Rice. Rice, who himself had been on a vessel for two months, was not in good form either, and after 65 consecutive wins lost his final race to Hägg before going off to war. Hägg dropped the American soon after four laps and had a 35m margin at the end with a very slow 14:48.5. Hägg’s comment after this slow race underlines the toll his trans-Atlantic trip had taken: “I was totally exhausted when I came in. So if someone had told me I was dead, I would have believed them.” (Ulf Ivar Nilsson, www.arbetarbladet.se, 2011)

Tougher competition was to come. And bad news too: on July 1, the day before Hägg’s next race, he heard that Andersson had broken his Mile WR with 4:02.6. The tougher American competition was not to materialize until late in Hägg’s tour. His next three races were relatively easy as he worked himself into racing condition. He won a couple of two-mile races in 9:02.6 and 8:53.9, before tackling his first Mile, which he also won in a slow 4:12.3. Gil Dodds had been racing him regularly but had not so far shown the form that had earned him the 1942 Indoor AAU title. But suddenly Dodds clicked in a late-July race in Boston and gave Hägg a good race, losing by only a second. His 4:06.5 behind Hägg’s 4:05.3 was a new American Mile record, by now 3.9 seconds outside Andersson’s new WR. Almost as impressive was the performance of Bill Hulse in third, who improved from 4:15.9 to 4:07.6.

A week later in Ohio, both these American runners pushed Hägg in another Mile. Hägg made the early running as usual, passing 880 in 2:02 and 1320 in a very fast 3:03. But Dodds and Hulse were still right with him. Hägg’s remorseless pace eventually told on Dodds, and Hulse passed him to take the American Mile record in 4:06.0 behind Hägg’s 4:05.4. Hägg was certainly helping to rewrite the American record book!

The trio had just one more Mile race. In New York 5,500 spectators watched Hulse set the pace with 59.6 and 2:03.5 for the first half. Hägg was finally in front at the bell (3:06.5). However, on the back straight Gil Dodds charged into the lead. It was the first time in Hägg’s tour that he had been led on the last lap of a race. But Hägg had no trouble regaining the lead, and he hit the tape in 4:06.9 from Dodds (4:07.2) and Hulse (4:08.2).

By all accounts Hägg performed well as an ambassador, attending banquets, giving speeches and generally promoting goodwill. He is said to have raised $150,000 for the US Army Air Forces Aid Society. And he was certainly a boon to American miling, especially to Dodd and Hulse. On leaving he gave his shorts to Hulse and a racing shoe each to Dodds and Rice. “I thank God for the strength that enabled me even to stay close to this great runner,” the Rev. Gil Dodds said after he had lost all seven races against the Swede. (Mel Larson, Gil Dodds: The Flying Parson.)

|

| Hägg poses in the cowboy outfit hebrought back from the USA. |

There is some interesting material on Gunder Hägg in Mel Larson’s biography of Gil Dodds: “Hägg liked his sleep. Some nights he would sleep the clock around. Before the race in Chicago, he slept from 11 pm to 11am. Then he got up, did a few limbering-up exercises, ate a little, and then went back to sleep.” Hägg’s diet varied: “One day he would eat two meals, the next day four.” He liked milk shakes and ate only the crust of pies. Dodds found Hägg “one of the most carefree persons [I] have ever met.”

Hägg didn’t have to endure another transatlantic boat ride. Instead he was flown home. It has been written that the plane he was supposed to take crashed. By the time he returned home, the Swedish track season was over, although he did run an exhibition 1,000 on October 10. His 1943 competitions were thus all carried out in the USA.

Considering the difficult transatlantic journey and the interruption in his training, Hägg had performed well in the latter part of his American tour. He had run three Mile races within 2.3 seconds of his 1942 PB, and he had run a couple of fast Two Miles times (8:53.9 and 8:51.3) that were only 3.5 and 6.1 seconds outside his 1942 WR. As well he had shown that his competitive skills were just as sharp; he had enjoyed yet another unbeaten season despite strong competition from Dodds and Hulse. Nevertheless, the relentless improvement in his PBs since 1940 had ground to a halt.

After his transatlantic adventure, Hägg didn’t return to serious training until January 1944. And then his training was interrupted when he left his job as a fireman in Gävle and moved to a job in a Malmö clothes store that had been arranged by a Malmo sports club.

Hägg put in only eight days of snow-running in the first 18 days of the year. Then for this move to Malmo, he took a week’s break. Now 600K farther south, he had little or no snow to train in. A different form of training evolved on bare ground (barmark). After ten days of light running, he spent two weeks running 3,000 hard every day except his weekly rest day. Only after 14 of these hard runs, did he start fartlek training, usually over his regular 5K distance. This fartlek continued through May until he went up to Vålådalen on June 1. His program there was the same as in 1942: easy runs of 5-6K in the morning, and in the afternoons fast runs in the forest over 3-6K. His pre-season training log makes no mention of speedwork.

1944 Season

Hägg’s stay in Vålådalen with Gösta Olander again produced results. Just as he had done in 1942, Hägg started his 1944 season with a world record. At the end of June he beat his own Two Miles WR in Östersund with 8:46.4, just 1.4 faster than in 1942. But three days later he was beaten for the first time by Andersson over 1,500 in Stockholm. Perhaps he hadn’t fully recovered from his Two Miles WR, but as the ensuing season was to show, Andersson had improved more than Hägg over the previous two years.

This Stockholm race must have been a shock to Hägg as he was truly trounced. The race went Andersson’s way from the start: a slow 62.9 was just what he wanted. Hägg realized that he had to up the pace and ran 60.1 for the second lap. But then, uncharacteristically, he let the pace drop again to 62.7 for a slow time of 3:05.7 at 1200. Andersson waited until the finishing straight to unleash a stunning finish that left Hägg 10 meters behind (3:48.8 to 3:50.2). Asked if he was saddened by the end of his three-year winning streak, Hägg replied diplomatically: “I feel neither glad nor disappointed. I know however that Arne will be all the more glad for it…and one can wish success to a good friend.” (The Milers, p.153) Still, Hägg must have done some serious thinking after such a sound defeat.

And what a comeback he made! After winning two minor races over 1,500 and 2,000, he met Andersson again over 1,500 nine days later in Gothenburg. He had watched Andersson run an incredible 2:56.6 3/4 Mile WR two days earlier. His rival looked unbeatable in that race. Clearly Hägg need to do something special. Paced by a then unknown called Lennart Strand, Hägg began the 1,500 with laps of 56.7 and 59.8. Andersson kept back somewhat: 5m at 400 and 3m at 800. But then he closed up on Hägg, both runners passing 1200 in a very fast 2:58.0. Andersson later admitted that he was really hurting at this point and felt like quitting. Hägg kept pushing at the front and gradually Andersson lost contact. Hägg’s strength was the difference, but he had needed to run at an almost reckless early pace to break his rival. “When he doesn’t hear me behind him,” Andersson once said, “he gets wings.” (Sports Illustrated, Aug. 2, 1971) Not surprisingly, Hägg was pushed to a world record of 3:43.0, an impressive 1.9 seconds faster than Andersson’s 1943 mark. Andersson himself also ran brilliantly, running one second faster than ever before with 3:44.0. It took what may well have been Hägg’s bravest race—he clearly was not in his 1942 form—to win this race and break the 1,500 WR.

|

| Andersson's greatest victory over Hägg in the 1944 Malmö Mile. Hägg, still affected by his USA trip, cannot hold off his determined rival.Andersson clocks 4:01.6, Hägg 4:02.0. |

A week later in Stockholm, Andersson got his revenge over another 1,500. His win was more tactical and the slow time (3:48.4 to Hägg’s 3:49.2) meant the race got less publicity. But Andersson earned his publicity four days later in Malmö, this time over a Mile. Their rivalry was now really drawing crowds. Three hours before the meet was to start, huge crowds had lined up outside. When the gates closed after admitting 14,279 spectators, there were at least 4,000 denied entrance; some of them scaled the fences anyway. The already excited atmosphere was heightened when it was announced that the popular young Lennart Strand had been added to the Mile field. And it was Strand again did the pacemaking with Hägg and Andersson not too far behind: 56.8 and 1:56.0. Hägg was timed at 1:56.7. This was 3:53.4 pace!

Around the next bend Hägg closed right up on Strand, passing him on the back straight. As is often the case in a Mile, the pace slowed in the third lap, Hägg covering the two 200s in 31.5 and 31.0. The green-vested Andersson was right on Hägg’s heels at the bell. The time was under 3:00 (accounts give various times from 2:58.5 to 2:59.8). Andersson still managed to hang on as Hägg ran the next 200 in 31.8 and they passed 1,500 in 3:46.0 and 3:46.1. No matter how hard he tried, Hägg just couldn’t break Andersson and was passed in the final metres. Andersson 4:01.6; Hägg 4:02.0. The two fastest Mile times in history. The crowd ignored the public announcement asking that programs not be showered on the winner as he made his ceremonial lap. Then once Anderson had done his lap, the crowd chanted for Hägg, who was pushed into doing a lap as well.

Andersson and Hägg might have been bitter rivals on the track, but otherwise they were the best of friends, and that night they dined together. Andersson even offered Hägg some advice to run faster: “Gunder, why do you run so wide around the curves. I always gain on you there.” (The Milers, p.155) The rivalry between the front runner and the sitter had become a race promoter’s dream.

Before they met again, Hägg yet again improved his 8:46.4 Two Miles WR—on the second attempt. After running 8:47.2 on July 25, he tackled the same distance on August 4 in Stockholm. He ran the first mile exactly on his WR pace (4:23.0) and then was able to speed up to a 4:19.8 second mile for an 8:42.8 WR that was to stand for eight years. And in between this pair of two-mile races, he came very close to his 5:11.8 WR for 2,000 with 5:12.0. It seemed like Hägg was running into the best form of his life. However, Hägg was about to undergo three consecutive defeats by Andersson. The man he beat every time in 1942 now had his number. Previously he could outrun Andersson from the front; now Andersson had improved to the point where he could hang on to Hägg and then exploit his kick.

The first of Hägg’s three defeats by Andersson came in the Swedish Championships. Perhaps discouraged that his front-running tactic was no longer working, Hägg allowed the race to evolve at a slow 3:50 pace. This played into Andersson’s hands, and Hägg had to fight hard to get second place from another Andersson—Bertil. Andersson clocked 3:49.6 to Hägg’s 3:50.0. A week later Andersson again outsprinted Hägg in a fast 2,000, winning in 5:12.6 to Hägg’s 5:13.2. And finally in Malmo, Hägg again made no effort to burn off his rival. Andersson showed his speed in a slow 3,000, winning by 1.6 second in 8:22.4.

Although he had set three WRs in 1944, Hägg had lost six out of seven races against Andersson. Was he burning out and losing some of his racing zest? Perhaps, but he finished the season with three impressive victories over the visiting Finnish star Viljo Heino, who had just knocked 17.2 seconds off the 10,000 WR with 29:35.4. Surely the answer would come in 1945.

America Beckons Again

Hägg’s training began earlier that usual for the 1945 season because he accepted another invitation to the tour the USA, this time for the indoor season. He started with some light running on November 25th. In the middle of December he traveled up from Malmo to Vålådalen to train in the deep snow. Then, back in Malmo, perhaps pushing himself too hard, he got sick just before his trip.

Probably because of his ‘flu, Hägg’s second American tour was not a success. As well, he had no experience of indoor racing. He was fifth and last in his first race in New York, a Mile in which he clocked an embarrassing 4:31. He wasn’t much better a week later, finishing fifth in the Columbia Mile in 4:19.1. In two more races he ran second and then first, but in mediocre times (4:14.5, 4:16.7). Unable to get a passage home, he stayed on for another month and raced the Penn Relays, where he was only fourth in 4:12.7.

It’s not clear exactly what Hägg’s motive was for this eight-week tour. This time there was no mention of an ambassadorial role, so it is likely that his interest was in the American way of life and perhaps in making some extra money before he retired. Even after taking into account his early ‘flu and the rigours of travel in the 1940s, it was clear that all was not well with the multi-world-record-holder.

1945 Season

|

| Hägg in his typical role as a front runner with Andersson in tow. |

On returning much later than he had hoped (May 22) after a difficult transatlantic trip, Hägg got straight into twice-a-day training. He had only nine days of training before his first race, and the intensity of his sessions suggests a concern over his condition. Every morning he did a hard run of 4K; in the evenings he also ran hard, doing either 5K of fartlek (six times) or hard 4K runs (four times).

It was to be a bizarre 1945 season with 30 low-key races and one surprising world record. After three 1,500s around 4:00, Hägg went up to Vålådalen for a week. Things looked bad as he had not run faster than 3:57.8. But the magic of Olander and Vålådalen worked again. In his next race he dropped his time to a respectable 3:51.4. Admittedly he had faced no real competition so far, but there was little indication of what was to come in his first 1945 race with Andersson. On their current form, Andersson, with three fast 1,500s (3:46.8, 3:45.0, 3:47.0) was a clear favorite.

This Mile race was held in Hägg’s new hometown of Malmö, where Andersson had beaten him the previous year in a WR time. Clearly Hägg was desperate to prove to his neighbours that he was the better miler, but he must have found it hard, based on his recent times, to summon up the confidence needed by a front runner.

There were only three other runners in the field: Strand, Persson and Ake Pettersson. The tension was evident in the false start. Pettersson made the early pace with a 56.2 first lap. It was too fast, but he evened things out in lap two with a 62.3 for 1:58.5, before dropping out. Hägg, who had urged Pettersson to go faster on the second lap, then took over and ran a 61.2 lap to reach the bell in 2:59.7. He powered on but was only just ahead of Andersson at the 1,500 mark (3:45.3). The race was evolving in exactly the same way as the 1944 Malmo Mile, the only difference being that Hägg took the lead earlier this time.

And it looked like the result would be another win for Andersson, as he held on to Hägg round the bend and then moved up beside him. Not this time. Showing incredible competitiveness, Hägg was able to respond to Andersson’s challenge, and he moved clear to win in a new world-record time of 4:01.4, just 0.2 ahead of Andersson’s WR mark. This race underlined what a great competitor Hägg was when motivated. It took a huge effort for Hägg to beat his improved rival: “I could not have run even one-tenth faster,” Hägg said later. “I staggered dead beat over the line.” (Sports Illustrated, Aug. 2, 1971) Anderson held on for 4:02.2. Rune Persson’s brilliant 4:03.8 in third was all but forgotten in the excitement of the race for first place.

|

| Hägg and Andersson in full flight. |

It wasn’t until after the race that it was discovered that Andersson had run much of the race with a starter’s cartridge lodged in his spikes. One can only surmise how much that handicapped the gallant loser; it must have required a lot of mental strength to continue running with such an impediment. Hägg, as usual, was full of praise for his rival, telling him, “You’re a great opponent. I was really scared.” He claimed he had not felt good earlier in the day: “At the start it looked like a bad day for me. Very few customers showed up at the store. Seeking a better mood, I slept a few hours after lunch, but apprehension was still in my limbs when I woke up.” (The Milers, p.161)

Surprisingly, in view of their practice in earlier years, Hägg and Andersson raced each other seriously only once more. This wonderful Malmo Mile was really their swansong. They both continued a furious racing schedule. Hägg competed into October, winning all but two of his races in what for him were mediocre times. It was becoming increasingly obvious that his motivation was waning. This was underlined in a Mile race in late September, where for once he raced against top competition. He finished fourth in 4:13.2, behind Strand, Andersson, and Hansenne of France, more than eight seconds behind the winner. This was not the Gunder Hägg of 1941 and 1942. After three 3,000 races in the 8:30 range, his 1945 season was over.

|

A rare scene: Andersson pacemaking for Hägg in 1942. This Two Miles was won by Hägg in 8:47.8, a world record. |

Last Act

Apart from his Mile WR, Hägg’s 1945 season showed signs of wear and mental fatigue. True, he won all but two of his 23 races, but very few of them were against strong competition. As well, his times were well below his best. For his five 1,500s he averaged 3:54.8; for his eight 3,000s he averaged 8:30. The fact that he had “done it all” with world records at 1,500, One Mile, 2,000, 3,000, 2 Miles, 3 Miles and 5,000 left him with no real goals (no international championships were being held in wartime). As well, after a warning in 1944, he was being hounded by the Swedish authorities for the money he was receiving from race directors. So in 1945 he must have been thinking a lot about a life beyond his running career.

As it turned out, the future of his running career was decided for him. Over the winter of 1945-46, the Swedish federation, Svenska Idrottförbund, investigated the issue of under-the-table payments to amateur runners. In March of 1946, Hägg was banned for life together with Andersson and Jönsson-Kalarne. He did not appear at all upset and started to talk about his retirement plans. So Hägg’s career was terminated, just as it had been for Ladoumègue and Nurmi, by what are now regarded as antiquated amateur rules.

There was an ironic twist to this story in 1954. On the day that Bannister broke Hägg’s Mile WR of 4:01.4 and the four-minute barrier, Hägg was stopped for speeding in Sweden. The policemen, on recognizing the running celebrity, informed him of Bannister’s achievement and in sympathy let him go without a ticket. Hägg lived and long life and remained lifetime friends with Arne Andersson.

Retrospect

In later years, Hägg was asked many times whether he could have run a sub-4 Mile. Naturally, he claimed that he could have. But his justification needs questioning: “If Arne and I had cooperated, we would have broken the four-minute mile. But, to us, the most important thing was to win. We never had the idea of co-operating. I never thought about times.” (Times, April 23, 2009) Apart from the obviously untrue last sentence—why were there so many pacemakers in his big races?—the cooperation aspect needs analysis. How would cooperation between Hägg and Andersson have worked better than the pacemaking by third parties? Hägg always did a lot of the leading in the later stages creating a perfect set-up for Andersson. How could Andersson have contributed? Would his leading in the first lap have been a help at all? Only perhaps for Hägg if Andersson had managed to run at the right pace. In short, Hägg always set up Andersson perfectly for a fast time; Andersson’s best contribution was to breathe down Hägg’s neck and push him. The only way that they might have run faster over a Mile or 1,500 would have been to find someone who could run a good third lap as Chataway did for Bannister in 1954. A slower first lap in their 1944 and 1945 Mile WRs might have helped them go faster, but probably not enough to break 4:00. In short, Hägg probably reached his limit when running 4:01.4 in Malmo on July 17, 1945. Still, had he not made two demanding American tours, he might well have run faster.

Good fortune certainly smiled on Hägg. First, he was lucky to be living in a neutral country during his early 20s while most of his age group were fighting in a world war. Second, coming from such a remote area of Sweden, he was indeed fortunate to have a great runner and a fine coach (Jönsson-Kalarne and Gosta Olander) living nearby. Third, his early years working for his father gave him ideal general conditioning and body-core strength. And fourth, he benefited greatly from having such good competition from Andersson.

However, all this good fortune would not have been enough to take him to world-class standards. Hägg’s own intelligence and self-discipline were also crucial. Despite his limited formal education, he was able to learn from others, develop a training program, and then stick to that program for considerable periods and through many adversities. As well, his competitiveness enabled him to rise to the occasion when in mattered. It’s difficult to find a major race in which he didn’t perform well.

Had he not been tempted into making two trips to the USA, which disrupted the effective winter conditioning system that he had developed, he might well have run faster in 1943, 1944 and 1945, before his lifetime ban took effect. He might even have run under 4:00 for the Mile.

2 Comments