Bob Phillips Articles / PROFILE

Jules Ladomègue: Julot, the French Idol

By Bob Phillips

27th March 2024

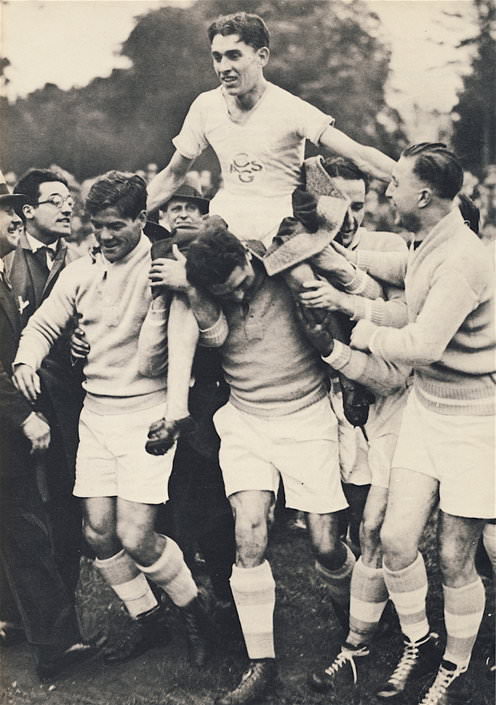

Julot, the French idol. “Above all of us others”, said Nurmi The life of Jules Ladoumègue

Author’s note: John Cobley’s profile of Jules Ladoumègue on this website covers his competitive career in admirable detail, and this article is intended to complement that. Living in France, I can hopefully bring a further perspective to the contribution made to French athletics by Ladoumègue, with whom all subsequent middle-distance record-breakers from that country are still compared.

Deprived of his bid for Olympic glory, the World record-holder was likely in need of consolation, and who better to provide it than the man who had already won gold medals galore ? Paavo Nurmi wrote, “From the time when I left the mile to be run by younger men, new talent has appeared at that distance. The overwhelmingly outstanding one among them is the Frenchman, Ladoumègue. I have never had the opportunity of running against him, but I have often seen him at it. Ladoumègue’s results raise him as a miler above all of us others”.

Nurmi composed these words for one of a series of articles about his competitive career which was syndicated internationally to newspapers early in 1932. The Los Angeles Olympics were four months away, but ironically neither Nurmi nor the man he so much admired, Jules Ladoumègue, would be there. Both were banned for transgressing the stringent rules regarding amateurism. Nurmi had planned to run the marathon in Los Angeles, having already won eight gold medals on the track since 1920. Ladoumègue would have been the favourite – “overwhelmingly” so, as Nurmi would have put it – for the 1500 metres, to go one better than his silver medal from 1928.

Both of them had no doubt profited materially from athletics, and Ladoumègue, in particular, would have been under scrutiny ever since he started competing in his early teens. Born into a working-class family in the south-western city of Bordeaux on 10 December 1906, he had the misfortune never to know either of his parents. His father was killed in a timber-yard accident before the boy’s birth and his mother died in a domestic fire tragedy when he was only 17 days old. He was brought up by an uncle and aunt, and an elder brother and sister were sent to other relatives. He was already winning local village-to-village races from the age of 13, and was accepting cash prizes for doing so, maybe in all innocence, having left school to work as a horticulturist’s apprentice. Realising his potential after he had won the south-west regional cross-country title for under-15s, the Fédération Francaise d’Athlétisme (FFA) required him to pay them the 500 francs or so he had earned in winnings in order that he could be reinstated as an amateur – a fine example of characteristic French pragmatism, strengthening resources and at the same time making a profit !

Having first impressed in senior ranks with 3rd place in the national championships 5000 metres in 1926, there was a curious tale concerning Ladoumègue’s selection for the match against England (in effect, Great Britain) in Paris in July that year. The coach to a rival athlete who was left out of the team apparently told the FFA that he would denounce Ladoumègue for professionalism to the English Amateur Athletic Association, but some sort of compromise must have been reached because Ladoumègue duly ran in the match and finished 3rd in a race won, incidentally, by H.A. (“Johnny”) Johnston, the future coach to marathon record-breaker Jim Peters, with an Olympic marathon silver-medallist to be, Ernie Harper, in last place. Did Jean-Joseph Genêt, the FFA president and himself a distance runner of the 1890s, successfully refute the claims against Ladoumégue ? Or did he come to an agreement with the accuser that it was in everybody’s best interests not to pursue the matter ? Had M. Genêt but known it, this would be a recurrent issue.

In 1927 Ladoumègue set national records for 2000 metres, 3000 metres and two miles and was 5th-ranked in France at 1500 metres, where there was some impressive strength in depth. René Wiriath was 2nd fastest in the World at 3:56.2, one-tenth behind one of the least known “Flying Finns”, Leo Helgas, and there were five other Frenchmen in the top 30 in the World, among them Ladoumègue, equal 21st at 4:01.6. Even so, in the England-v-France match at Stamford Bridge on 30 July the French trio at 1500 metres were 3rd, 4th and 5th (Ladoumégue), well beaten by John Moore (3:59.0) and Stan Ashby (3:59.3). By now Ladoumègue had left Bordeaux for Paris, transferred during military service to the Joinville Battalion which was, to all intents and purposes, a multi-sports association. He also joined the Stade Francais club, where his coach was Charles Poulenard, who had set a national 800 metres record of 1:57.6 in the heats of the 1912 Stockholm Olympics.

In the Olympic year of 1928 Ladoumégue produced national 1500 metres records of 3:54⅗ and then a startling 3:52⅕ within a fortnight in July, which put him among the Amsterdam Olympic favourites, together with two Finns, Harri Larva, who had run 3:52.6, and Eino Purje, 3:53.1. The World record had passed from Nurmi’s 3:52.6 in 1924 to 3:51.0 by Otto Peltzer, of Germany, in 1926. Nurmi’s preference for longer distances meant that he would run (and win) the 10,000 metres at the Games. Peltzer was entered for both the 800 and 1500 metres, but the 1500 metres heats on 1 August were marked by his elimination, as had also already happened to him in the 800 metres semi-finals.

The best represented countries in the 1500 final on 2 August were Finland (Larva and Purje), France (Ladoumègue and Jean Keller) and Germany (Herbert Böcher, Hans-Helmuth Krause and Hans Wichmann). The other five who qualified were William Whyte (Australia), Adolf Kittel (Czechoslovakia), Cyril Ellis (GB), Paul Martin (Switzerland) and Ray Conger (USA). When the race came down to the medal contest, there were really only two men left in contention after Purje had made much of the earlier pace. These were Larva and Ladoumègue, and Larva won, 3:53.2 to 3:53.8, with Purje almost three seconds behind but saving the bronze from Wichmann. Ellis was 5th, Martin 6th, Krause 7th and the rest were outside four minutes. Ladoumègue should have had the gold, according to André Greuze, who was a renowned Belgian journalist and co-founder of the Association of Track & Field Statisticians in 1950. He wrote in 1968, “It looked as though he would win when he committed the unpardonable error of looking round three times in the home straight, and he was caught and passed 50 metres from the end by Larva”.

The spectre of the draconian amateurism code was raised very soon after when the FFA suspended for three months Ladoumègue and a clubmate, Séraphin (“Séra”) Martin, who was no relation to the Swiss Martin but was World record-holder at 800 metres (1:50.6) and previously at 1000 metres (2:26⅘). The details of what happened regarding the ban are confused, as they so often are in such cases, and it was stated that sums of as much as 7000 francs (worth in 2023 terms just over 1000 euros) were asked for on their behalf regarding their participation in a proposed tour of Japan by a team of French athletes, though the correspondent for the Associated Press news agency in Paris was adamant that the pair had been disciplined for not appearing as promised when the athletes departed on their long journey. Yet they had also been banned from overseas competition for a year, but whatever the circumstances the full sentence was not served because Ladoumègue was in Germany for more than a week in the summer of 1929, winning at 1500 metres in Cologne on 31 July and Nuremburg on 7 August but losing to Larva again in Berlin on 4 August.

During 1930 and 1931 Ladoumègue – by now known fondly throughout France as “Julot” – became the leading middle-distance runner, entirely worthy of Nurmi’s fulsome tribute. He set World records at every distance from 1000 to 2000 metres, as follows:

1500 metres: 3:49.2 Paris (Stade Jean Bouin), 5 October 1930

1000 metres: 2:23⅗ Paris (Stade Jean Bouin), 19 October 1930

2000 metres: 5:21⅘ Paris (Stade Jean Bouin), 2 July 1931

¾-mile: 3:00⅗ Paris (Stade Yves de Manoir), 13 September 1931

1 mile: 4:09⅕ Paris (Stade Jean Bouin), 4 October 1931

The most historic of these were, of course, the 1500 metres and the mile, in which he became the first man to beat 3min 50sec and 4min 10sec. His predecessors as World record-holders were of the elite of the 1920s – at 1000 metres and 1500 metres Peltzer, 2:23⅘ in 1927 and 3:51.0 in 1926; at one mile Nurmi, 4:10.4 in 1923. The record for the rarely run ¾-mile had stood at 3:02⅘ to Tommy Conneff, of the USA, since 1895 ! The 2000 metres record, favoured since the days of World War I by the Scandinavians, was 5:23.4 by the Amsterdam Olympic 1500 metres bronze-medallist, Purje. Ladoumègue also ran an esoteric 2000 yards in 4:52.0 in Stockholm on 12 July 1931, beating by more than 15 seconds Alfred Shrubb’s time from 1903. His best 5000 metres of 15:03.2 got him 15th ranking in the World in 1928, but he abandoned the event thereafter.

Ladoumègue made full use of Séra Martin and Jean Keller as pace-makers and had his record-breaking attempts set up for autumn-time because despite his south-western origins he disliked the heat of summer. There had been a sort of “sneak preview” in 1930 of what was to come when Ladoumègue made his first appearance in Britain at the England-v-France match at Stamford Bridge on 2 August, hailed beforehand by the press as ”the crack miler” (“crack” in those days meaning “outstanding”) and “said to be second to none in the World”. He had run a 3:53.8 for 1500 metres the previous month, and though the English trio of Jerry Cornes, Cyril Ellis and Reg Thomas was as strong as any country could muster the result was not long in doubt. “He was always master of the situation”, reported Harold Abrahams in his weekly “Athletic News” column. “A half-mile in 2:06⅕ worried Thomas and finished Cornes, and Ladoumègue passed the finishing-line well within himself”.

Ladoumègue had not been so timely when the team had set off for England on the 8.25 a.m. train from Paris the previous day, and the management must have been seething that there was no sign of him until news came through that he had taken the noon train instead, and he duly caught up with his team-mates for a sight-seeing visit to Stamford Bridge that evening. The same day that his mile win in the match was reported, the Reuter’s news agency cabled from Berlin that Otto Peltzer had been suspended by the German ruling body for failing to supply an expenses account from a recent overseas tour.

The most respected of French athletics writers, Gaston Meyer (1905-1985), set the chronological perspective in a book he wrote in 1966: “Ladoumègue by fortune or ill-fortune was placed at a cross-roads of two eras in athletics. Since Ted Meredith and even Walter George the shorter middle-distance events – 800 metres to the mile – had only progressed slowly. Because he was the first to train every day, Paavo Nurmi was the holder for a certain amount of time of the records for 1500 metres and the mile. The middle distances, despite Lowe, despite Peltzer, stagnated. After Ladoumègue, disqualified at the age of 25, the events blossomed, and he never had the chance to confront the rising and voracious generation of the years 1933 and following”. Meyer’s image of the likes of Lovelock, Beccali, Cunningham, Bonthron and Wooderson greedily consuming World records is a splendidly vivid one !

The statistics backed Meyer’s judgement to the hilt. By 1931 the mile record, whatever the circumstances, had advanced little more than three seconds in the 45 years since Walter George had run 4:12¾ as an acknowledged professional in 1886. In the next eight years after Ladoumègue’s sub-4:10 the record improved five seconds to Glenn Cunningham’s indoor 4:04.4. In the seven years after that the sublime Swedish duo, Hägg and Andersson, would cut a further 3.1 seconds in the seclusion of wartime neutrality.

Meyer was also most expressive in describing Ladoumègue’s appearance: “If one applied to athletics the terminology of architecture, one would describe the Ladoumègue style as ‘flamboyant’. He was the man of the divine stride, supple and light, stretching widely across the cinders”. Another French writer with a lyrical touch, Roger Debaye, developed an even more exotic theme, declaring in 1986: “Franz Schubert was only 25 years old when he wrote what would become one of his master works, ‘The Unfinished Symphony’. Jules Ladoumègue was exactly the same age when the sanction against him of 4 March 1932 made his career another ‘Unfinished Symphony’. Unfortunately, the comparison ends there because Schubert went on to write the celebrated ‘Trout’ symphony, 22 operas and 600 lieder songs, while our Julot was no more than a man handicapped, demeaned by second-rate show-biz spectacle – more precisely, running round circus rings or along a conveyor belt on stage at the Casino de Paris surrounded by girls kicking their legs high”. The dexterity of Ladoumegue’s legs attracted even more excitable attention than those of the chorus-line, however seductive. Although he was only of average height, 1.74m, his stride length was measured at 2.25m.

Roger Debaye had been a capable long jumper in the years 1930-31 and became a film-maker who also remembered a much more appealing aspect of the post-competitive activities of Julot. Debaye, accompanying him on promotional tours sponsored by an aperitif company, wrote: “All the youngsters in a village would be brought together to run a kilometre, or even another kilometre, with him, and this would be a crazy success because even 10 years after his disqualification his popularity was still immense”. Debaye’s reflections are not at all surprising because the average Frenchman or Frenchwoman has an endearing habit (and sometimes a mystifying one) of maintaining an unwavering lifelong loyalty to the heroes and heroines of their youth, whether they are singers or stars of stage, screen and sports arena.

Ladoumègue had been convicted by the FFA for what might be considered an understandable abuse of the system. His race prizes were in the form of orders placed at department stores for goods to the value of 4000 francs, and Ladoumègue simply bought articles worth a few hundred francs and took the balance in cash, which the store-owners presumably found acceptable. Judging the matter from a practical point of view, and considering his frequent race wins, maybe he and his wife, who gave birth to their first child, a boy, at the beginning of 1932, had all the domestic appliances they could possibly need, and by now a mere fruit-bowl or a flower-vase was of more use to them than another vacuum cleaner. More seriously, the German and Swedish ruling bodies were apparently ready to submit evidence to the IAAF of demands made on Ladoumègue’s behalf for hefty appearance fees, implicating French officials. So it could be surmised that the lion-hearted runner with the grace of a gazelle was made a sacrificial lamb.

One of the more intriguing aspects of the whole sorry affair is the timing of it. The FFA clearly felt that action needed to be taken, and they were maybe pressurised by the IAAF, though apparently it was not a unanimous decision. According to Loys Van Lée, who was a celebrated athletics and rugby football writer for the daily sports newspaper, “L’Equipe”, the FFA secretary-general, Paul Méricamp, had done everything he could to absolve Ladoumègue, but “some directors got on their high horses regarding principles, such as Messrs Jacob and Annibert, remaining inflexible and caring nothing for France winning a gold medal at the 1932 Games”. In their April 1933 monthly bulletin, the FFA published a sorrowful editorial about what they called “Le Schisme Ladoumègue” in which it was claimed, “Public opinion – that is to say, the newspapers – have for the last year taken Ladoumègue’s side without knowing the facts of the case”. Even though bemoaning the creation of a “Ladoumègue mystique”, the FFA writer still hailed him as “the aristocrat of French athletics”. A love-hate relationship, perhaps ?

In Los Angeles Italy’s Luigi Beccali won the 1500 metres gold from Great Britain’s Jerry Cornes, who had been allowed to delay taking up a Colonial Service post in Nigeria. The ubiquitous Canadian, Phil Edwards, was 3rd, as he already had been at 800 metres, and he would add another bronze medal in the 4 x 400 metres relay. Future mile record-breakers Cunningham and Lovelock were 4th and 7th respectively and the 1928 champion, Larva, was 9th of 10. Beccali’s time was a Games record 3:51.2, which no doubt impressed Nurmi in his new role in the press-box but probably not Ladoumègue, also accredited as a journalist on behalf of the extreme left-wing Paris newspaper, “L’Intrasigeant”.

Before the Games had even started the pair of them must surely have been wryly amused that the IAAF, meeting in Los Angeles on 29 July, approved as official World records seven of their performances – four by Ladoumègue (1000 metres, 1500 metres, 1 mile, 2000 metres) and three by Nurmi (2 miles, 6 miles and 20,000 metres, all in 1930). It seems odd, to say the least, that the denizens of pure-blooded amateurism, including among its Council members the same Jean-Joseph Genêt who had endorsed the decisions which had led to Ladoumègue’s disqualification, should still readily accept the transgressors, whose “crimes” would have facilitated their achievements, now given unfettered amateur credence !

The news from the USA – or, more specifically, from Chicago – in the year following the Los Angeles Olympics would have given Ladoumègue cause for thought. Glenn Cunningham ran the fastest ever indoor mile of 4:09.8 in March, which was only six-tenths slower than the Frenchman’s outdoor World record, and then in open air Cunningham repeated that time exactly in the same city in June. A month later Jack Lovelock ran 4:07.6 at Princeton, New Jersey, with Bill Bonthron at 4:08.7 also inside Ladoumègue’s previous record. Ladoumègue took his enforced abdication in good heart, at least so far as his public reaction was concerned. “It is marvellous, sensational”, he told the French press. “Lovelock is a great champion and I am glad he has succeeded. I should like to try to win the record back, but I am afraid it is too late”. That rather gives the impression that Ladoumègue thought that, say, 4:07 was beyond him, but subsequent events were to prove that he still had ambitions so far as record-breaking was concerned.

He had begun his professional running career in March of 1933 with an eccentric indoor race of 1500 metres in 4:00⅘ against six three-man relay teams, and the next month, in a more serious frame of mind, he ran 3000 metres in Paris in 8:59⅖. In August he had a 1:53.4 for 800 metres, and on 10 September, at the Stade Buffalo in Paris, he easily beat his Finnish Olympic rival, Eino Purje, also now running for money, at 1000 metres in 2:29⅗. Maybe, though, Ladoumègue’s thoughts were straying elsewhere because the previous day, in the International Student Games in Turin, his 1500 metres World record had been equalled by Luigi Beccali, with Lovelock six-tenths behind. A few days later Ladoumègue and Lovelock met up, but it was at a social get-together rather than on a cinder track.

Lovelock had ill-advisedly, by his own admission, accepted an invitation to make a 1500 metres record attempt the following Saturday, 17 September, at Stade Colombes, and two days beforehand he and Ladoumègue exchanged pleasantries at a press lunch. It seems curious that the FFA should have organised such a race, and there was certainly plenty of opposition to the idea, as Lovelock was to explain in the detailed diary which he kept and which was published in 2008: “I was last to the mark. The crowd hissed and booed as I came along with cries of ‘Ladoumègue ! Ladoumègue !’. It was the first time I had ever struck a hostile crowd and it seemed to me so funny that I had to stop and turn and laugh at them, with the result that before long they were laughing with me”. A local runner named Badin braved the further wrath of the onlookers by making the pace for 900 metres, but Lovelock fell well short of the record, with 3:52.8.

“The crowd gave me a splendid hearing all the way, especially the last 600 metres, and tremendous applause at the end, particularly when they realised that Jules’s record was safe”, Lovelock wrote. What nobody at Stade Colombes knew that afternoon was that in Milan, where the Italy-v-GB match was taking place, Beccali was almost simultaneously running 3:49.0. Ladoumègue had already planned an attack on the existing record and, of course, two-tenths of a second improvement made little difference to the challenge. On 9 October he ran a ¾-mile “demonstration” in 2:59.2, which beat his own World record from 1931 and must have given him much confidence for a 1500 metres on his favoured Stade Jean Bouin track five days later.

He gathered together some willing pacemakers, and though they were not of the quality of Séra Martin, now retired and apparently not to be lured away from his trade as a mechanic, and Jean Keller, winning his fourth successive national 800 metres title before taking up sports journalism, they did their job well enough – though probably not so in Ladoumègue’s opinion. He ran 3:50⅘ and had three more attempts in the next three weeks of 3:51⅖, 3:50⅖ and another 3:50⅘. It was a nice irony that all of these artificial and unofficial forays required FFA approval of the use of the track ! In 1934 he ran 3:55.0; in 1935 1:53.9 for 800 metres in Moscow and an unconfirmed 3:53.8. No successor emerged among the amateurs in his native land during the 1930s, as the fastest times were 3:53.6 by Roger Normand in 1935 and Robert Goix in 1936.

The French public, as had been volubly expressed when Lovelock paid his vain visit, cared nothing for whether Ladoumègue had made money, and it was the unfortunate Méricamp who bore the brunt of their anger at their hero’s fate. When France met Great Britain at Stade Colombes in 1934, the British again took the first two places at 1500 metres (Jerry Cornes and Aubrey Reeve) and thousands of spectators demonstrated noisily, chanting, “Méricamp resign ! Julot ! Julot ! Julot !”. The “Daily Mirror” in London reported, “The victory of Cornes was followed by a violent demonstration that lasted for about 10 minutes and drowned out any attempt to announce the result of the race”. Cornes, accustomed to unruly public protests in the course of his Colonial Service duties, probably remained unperturbed. Paul Méricamp, too, rode out the storm, later serving as FFA president in the years 1937-1942 and 1944-1953.

In 1935 an estimated 400,000 people turned out on the morning of Sunday 10 November to watch Ladoumègue run the length of the Champs Elysées as an act of defiance and as a parade of honour organised by the “Paris-Soir” newspaper, with a host of celebrities, including nationally famous champion boxer Georges Carpentier and music-hall entertainer Maurice Chevalier, leading the plaudits along the way. Maybe Ladoumègue knew that further chastisement was imminent. He had just returned from a six-week tour of the USSR, during which he had run his 800 metres in 1:53.9, close to his fastest ever, and 1500 metres in 3:53.8, with no local opposition to press him as the Soviet Union national records for 800 and 1500 metres then stood at 1:56.4 and 3:59.9.

The USSR was not affiliated to the IAAF and would not compete internationally until 1946 or at the Olympics until 1952. So their authorities were free to do whatever they wanted, but the watchful FFA still had a hold over Ladoumègue. They had employed him as a sort of roving ambassador at a salary of 1000 francs a day but had terminated that contract, and they now rejected his application for reinstatement as an amateur. Did they dislike his ideological connections to his communist hosts, or was there simply a body of continuing anti-Ladoumègue opinion among the FFA hierarchy ?

.

Other athletes of Ladoumègue’s generation, including approved record-holders at that Los Angeles congress, could be said to also be materially privileged. For example, there were American college and university students whose tuition and accommodation was paid for in return for their track performances. Undergraduates at Oxford and Cambridge Universities (Jerry Cornes and Jack Lovelock among them) and members of the armed forces (including British Empire mile champion Reg Thomas, serving in the Royal Air Force), who were defending the British Empire in peacetime, had ample opportunity to train, with the facilities to do so conveniently close by. Yet athletes like Cyril Ellis, who was a mine-worker and had beaten Ladoumègue at 1500 metres in the 1929 France-v-England match at Stade Colombes, lost their wages when they needed time off to represent their country. Amateurism was an idealist concept founded by the British in the 19th Century which was fast becoming an anachronism. It existed in its unadulterated form only in the minds of the prosperous establishment who administered athletics, none of whom needed to worry as to where their next vacuum cleaner was coming from ! It would take another half-century to change such entrenched attitudes.

In World War II Ladoumègue was an infantry sergeant in the ill-fated French Army, and there was even some expectation that he would take part in a match against the British Army in April of 1940, but the German invasion of France soon put paid to that idea. When athletics competition was resumed under German occupation the FFA let bygones be bygones and in 1943 restored Ladoumègue’s amateur status. At the age of 36 he ran a modestly commendable 2:34.4 for 1000 metres but did not contest the national championships in which the 1500 metres was won in 3:58.5 by Marcel Hansenne, showing belated promise at the age of 26. That same summer in peaceful Sweden Arne Andersson was setting 1500/1 mile World records of 3:44.9/4:02.6, and there would be even better to come from him and his fellow-countryman, Gunder Hägg, in the next couple of years until they, too, suffered the same fate as their French predecessor and were banned for breaking the amateurism rules.

Ladoumègue’s place in middle-distance running history can be further exemplified by the fact that in 1928 he ran what would be the fastest times of his career for both 800 metres, 1:52.0, and 5000 metres, 15:03.2, ranking 9th and 15threspectively in the World that year. He can thus safely be regarded as the finest exponent of his era across that range of events. A remarkable compilation first published in 1982 proves the point because Hungarian statisticians Dr Bojidar Spiriev, Attila Spiriev (his son) and Gábor Kovács devised a remarkable set of scoring tables which compared performances in all events. This shows that Ladoumègue’s 800 and 5000 times are worth 1782 points, and Luigi Beccali’s score for times of 1:50.6 and 15:20.8 is 1763. As a matter of interest, Paavo Nurmi merits 1791 points for his 1:56.3 and 14:28.2. The “Hungarian Scoring Tables” equate Ladoumègue’s 1500 record of 3:49.2 with a mile in 4:07.34, which would not be surpassed until Glenn Cunningham ran 4:06.7 in 1934.

Ladoumègue resumed his journalistic career in radio and television after peace was restored in 1945. The wartime champion, Hansenne, persevered to start a sequence of breaking Ladoumègue’s national records, of which the ultimate improvements were 4:08.2 for the mile in 1945, 2:21.4 for 1000 metres (also a World record) in 1948 and 3:47.4 for 1500 metres in 1949. He legitimately combined competition with sports journalism, winning an 800 metres bronze medal at the 1948 Olympics. The legacy of Ladoumègue lasted to the very end of his life, and in February of 1973 French television broadcast a lavish tribute, inviting him to reminisce about his 1935 Paris command performance. He recalled, “It was my love affair with the people. The people of Paris recognised me that day in a manner which was most moving. It remains for me a very very happy memory”. Sadly, he died of cancer only a month later, 21 March, at the age of 66.

Another of those sublime French writers about athletics, Robert Parienté (1930-2006), who became editor-in-chief of “L’Equipe”, published in 1996 a weighty tome (896 pages) entitled “La Fabuleuse Histoire de l’Athlétisme” (no translation needed !), and in his chapter about Ladoumègue’s exploits left the last words to the athlete himself. Ladoumègue was quoted as having said, “The thought which has obsessed me the most all my life concerns the short career of an athlete. A singer, a musician, a writer fill their entire lives thanks to the gift which heaven has given them. Athletes are like dogs. They don’t live for long”.

Among dogs, Robert Parienté, might have added, Ladoumègue – frail of physique, majestic in stride – was a true greyhound.

Séra Martin and Jean Keller, pacemakers de luxe

Séra Martin and Jean Keller were no ordinary pace-makers. Jules Ladoumègue could not have asked for better when he set his 1930 World record 1500 metres. Martin held the 800 metres World record from two years before. Keller was the only man who had run in both the 800 metres and 1500 metres finals at the 1928 Olympics. Both would still be considered good enough to merit the considerable expense of being sent to the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics.

How generous of spirit these two were, whatever incentives they might have been offered, in selflessly helping out an old friend. Martin ran each of the first four 100-metre phases on the 450-metre Stade Bouin track in exactly the same time, 14.6 seconds, to pass 400 metres in 58.6, and Keller took over before 600 metres to reach the 800 in 2:00.4 and the 1200 in 3:05.0. The time of 2:33.0 at 1000 metres was 1.8 seconds faster than Peltzer had run on the way to his 3:51.0. A fortnight later Martin, Keller and René Féger, the national 400 metres champion, were the front markers in a handicap 1000 metres on the same track which created another World record for Ladoumègue. The next year Keller and others, including steeplechaser Georges Leclerc, were the aides in Ladoumègue’s successful assaults on the records for the mile and 2000 metres. René Morel, who was a 1:54.0 800 metres runner and would also go to the 1932 Olympics, was additionally brought in for the mile attempt, and the four 400-metre segments, again at the Stade Jean Bouin, were run in 60.8, 63.4, 63.8 and 61.2, which would have been considered classic pace-making in that era.

Leave a Comment