Profile: Ron Clarke

1937-2015

One of the great distance runners of the 20th century, this Australian broke new ground in the longer track races, just as Emil Zatopek had done 15 years earlier. Comparisons across different eras are difficult, but some statistics are illuminating. Clarke reduced the 5,000 WR by 9.2 seconds, Zatopek by 1.0; Clarke reduced the 10,000 by 38.6 seconds, Zatopek by 33.0. So Clarke wins on that score. However, competitively, Zatopek wins on an Olympic medal count with four gold and one silver to Clarke’s one bronze. This second comparison underlines the one flaw in Clarke’s career—his relatively poor competitive record in major races. Still, both men were for a time the dominant distance runner in the world. Perhaps the main difference between the two was that Clarke was more of a front runner than Zatopek. Zatopek had a race-winning kick, whereas Clarke, despite his claims to the contrary, did not. This comparison is not complete without acknowledging Zatopek’s great admiration for Ron Clarke. In 1966 Zatopek invited the Australian to Czechoslovakia, and as a parting gift he gave him his 1952 Olympic 10,000 medal with the following words: “Not out of friendship but because you deserve it.”

Olympic Torch Carrier

|

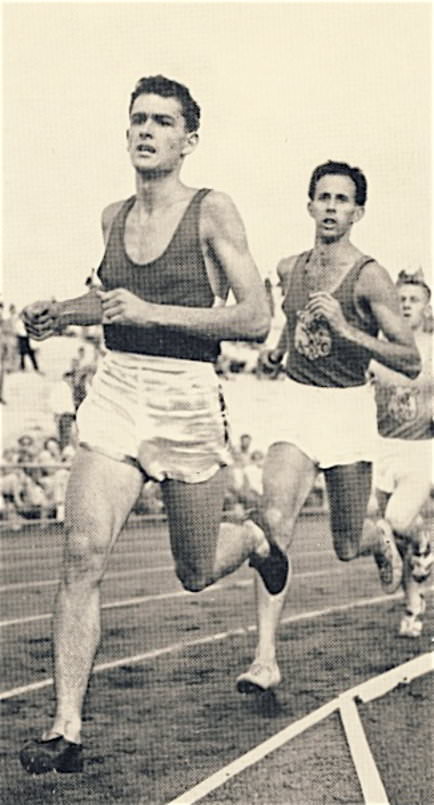

| Clarke leads John Landyin a 1956 race |

Clarke’s early career was full of promise. He emerged as a 17-year-old in 1955, running 4:19.4 for the Mile and 9:17.8 for Two Miles. Then in the 1955-6 season he ran a very impressive 4:06.8 Mile. Although he narrowly missed running in his hometown Olympics at the end of 1956, he was chosen to carry the Olympic torch into the stadium and light the Olympic flame: “The torch I was to carry was a larger, heavier model than the one brought from Greece. A magnesium compound threw out sparklers…. As I ran out on to the track there was a great roar that almost flattened me.… Chunks of burning magnesium fell back on my arm, but I was too excited to notice.” (The Unforgiving Minute, p.59)

Comeback at 23

One of the unusual features of Clarke’s running career was a four-year hiatus from 1957 to 1960, the years when he was 20 to 23 years old. These years are usually considered crucial years in a runner’s career. Clarke, facing senior competition and suffering from sinus trouble, found his attitude to running changing: “Lacking a fierce ambition to be a champion, it was easy to shrug off a decline in performances.” (TUM, p. 63) Although he kept fit during these four years, playing Australian rules football and other sports, he rarely ran seriously. He did compete for his club until 1959, but his times deteriorated to the point where he found it hard to break 2:00 for 880. Then he married and focused on his accountancy job and marriage. His weight went up to 178lbs and he joined a golf club.

It was only a home move in late 1960 that changed his attitude to running. He now had more spare time as he no longer had a 40-mile commute to work. So with his wife’s blessing he decided to take running seriously again: “I was nearly 24 and I estimated I had another six years or so in which I could take part in top-class sport.” (TUM, p.68) There seemed little chance of representing his country with Thomas, Vagg and Power on the scene, but he thought he could at least represent his state. So he started training, teaming up with a local friend, Les Perry, who ran for Australia in the 1952 and 1956 Olympics.

A big breakthrough came late in 1960 when Perry took Clarke to train on the Caulfield Racecourse. It was there that he met Trevor Vincent and Tony Cook, two leading Australian runners. They quickly became his regular training partners and a significant factor in his rapid improvement. In that 1960-61 track season, Clarke “didn’t win much” but he was satisfied with his progress. His best result was second place behind Tony Cook in the Victoria State 3 Miles. Only when he broke a finger playing football did he finally gave up the sport. That meant even more time for running and the inclusion of a long Sunday morning run between 17 and 22 miles.

October 1961 saw him running his first marathon, a “terrible” 2:53:09. He then ran 30:36 for 10,000 and a 14:23.2 for 5,000. Third-place finishes in the Victoria Championships earned him a trip to Sydney for the National 3 Miles. This race provided a breakthrough as he placed fourth with a 13:42 PB. All this encouraged him enough to train even more seriously over the 1962 winter. And although he entered the Commonwealth Games trials at the end of the winter, he never considered “the remotest possibility” that he would make the Australian team.

Commonwealth Silver Medal

But he did, finishing second in both the 3 and 6 Miles. In his first race at the Perth Games, the 6 Miles, he dropped out, unable to deal with the 90-degree heat. The 3 Miles was a different story. In a slow race, he was in with a chance at the bell, and while Halberg won the race easily, Clarke passed Tulloh and Kidd at the end of the race to surprise with a silver medal. Halberg himself was not surprised, telling the press: “You may not realize it in Australia, but Ron is one of the finest talents in distance running today.” (AW, Aug. 29, 1970) Although the rest of the 1962-3 season was an anticlimax (he did run a 4:03.4 Mile and an 8:44.4 2 Miles), Clarke had arrived on the international scene.

|

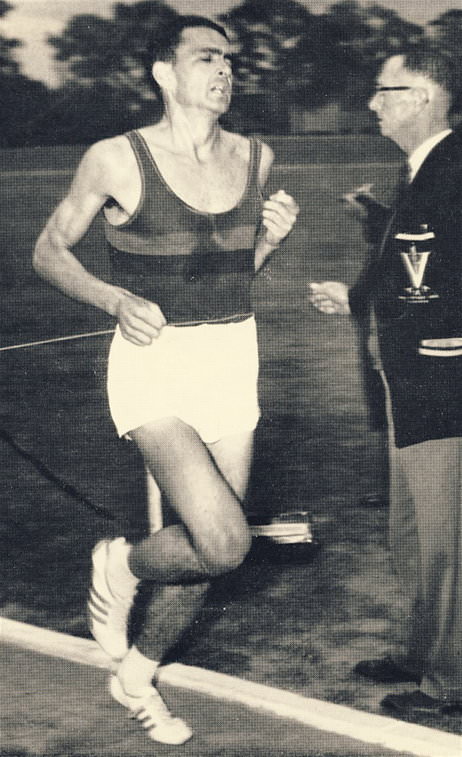

| His first world records.Melbourne, 1963 |

He worked hard during the 1963 Australian winter, adding weight training to his now twice-a-day training schedule. A victory in the Australian cross-country championships was an indication of continuing improvement. He also ran and won a marathon in 2:24:38. The ensuing track season saw his first two world records. 27:00 Six Miless. To start the 1963-4 season, he won a 10,000 race in 29:10.4, beating Dave Power and his two training mates Vincent and Cook. Next he ran a national record for 10 Miles in 48:25.2. More successful races over shorter distances followed and led up to a 6 Miles race in which Clarke wanted to attack the WR of 27:43.8 of Sandor Iharos. At this point he felt that Bolotnikov’s 10,000 WR of 28:18.2 was “unassailable.”

First World Records

Clarke worked out a schedule that would take him to a 27:40 clocking, but he was soon ahead of his schedule. He went through the first three miles in 4:25, 8:57 and 13:32. This was 27.04 pace and only four seconds slower than his PB for 3 Miles. Inevitably he slowed after this, dropping to 70-second laps. But he picked it up in the last mile with 69, 68, 68, and 64. He crossed the line in 27:17.6. At this point he dropped exhausted on his knees. Then he was told that he could also beat the 10,00 record, so he got up and finished the extra 380 yards for another world record world record of 28:15.6.

With eight months to go to the Tokyo Olympics, Clarke was suddenly a 10,000 favorite as the world-record holder. Still, despite his 26 years, he was still relatively inexperienced in international competition. True, he had run in the Commonwealth Games, but almost all of his races had been in Australia. To rectify this, he undertook a tour of indoor races in the USA and then in May he went to Europe for some top-level competition. In the States he raced against Bob Schul, Bruce Kidd and Gerry Lindgren; in Europe he raced against Pyotr Bolotnikov, Michel Jazy, Harald Norpoth. Such experience had two major benefits: it exposed him to the kind of tactics used in international races, and it gave him confidence. He later wrote: “In Europe I discovered that the crack distance runners we had read so much about were mere mortals who could be beaten like anyone else.” (TUM, p.103)

Reality in Tokyo

Sadly for Tokyo, this competitive experience was not quite enough. He still did not have enough self-belief to win either the 5,000 or 10,000. “Murray Halberg was to point out to me at the Olympics,” he wrote, “that, as a world-record holder, I had a great psychological advantage which I failed to use. A world-record holder should attempt to take charge of the race and make his opponents bend to his will.” (TUM, p.103) So although Clarke was in good shape, he did not perform up to the expectations of a WR holder.

|

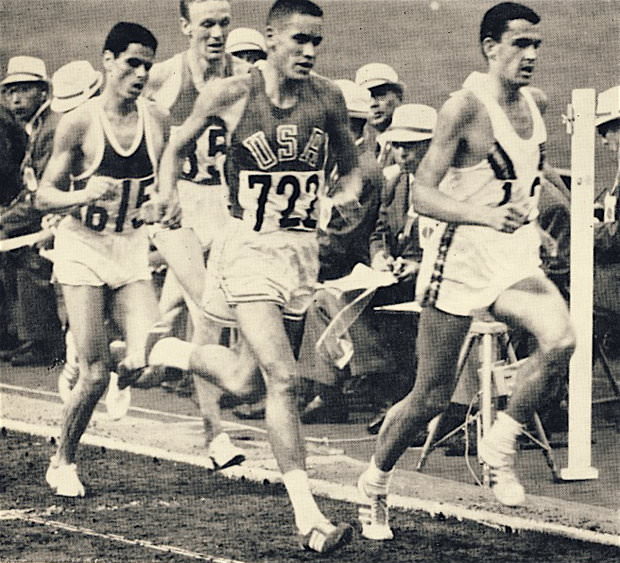

| Tokyo 10,000 at the bell. Clarke leadsMills (722) and Gammoudi (615) |

In the 10,000 he thought the race was his with eight laps to go. He had escaped all but three runners: Mamo Wolde of Ethiopia, Mohamed Gammoudi of Tunisia and Billy Mills of the USA. Clarke was using a surging technique that almost dropped Mills. Finally with 1,000 to go, he dropped Wolde. The last lap was chaotic as the three contenders lapped runner after runner. At one point Clarke and Mills collided, and Gammoudi took the opportunity to burst through between them for the lead, pushing Clarke aggressively with his left arm. With 200 to go Gammoudi had almost a 10-meter lead. But when he entered the straight, Clarke was at his shoulder. Clarke managed to stay very close as they neared the tape, but then Mills flew past on the outside, “flying towards the tape like a meteor,” as Clarke later described it. (TUM, p.19) The winning time of 28:24.4 was a fine time, only nine seconds slower than Clarke’s world record and run on a very loose cinder track. But Clarke, although he had run courageously to break the others, had not been able to put his stamp on the race in an authoritative way. His reward was only the bronze medal.

In the 5,000 he planned to put in two hard laps at the halfway point. But the early pace was so slow that he lost patience and took the lead and began to surge. But it was windy for this race, so leading was not a good idea. Clarke was now stuck in the lead as no one would take over. “Stupidly, I allowed the pattern of the race to upset me. I hadn’t bargained for this situation at all, and I couldn’t cope with it.” (TUM, p.116) And when Dutov of the USSR flew by and took the field with him, Clarke was left behind. He finished ninth and wrote that this race was “the one performance of which I am ashamed.” (TUM, p.109) He went on to run the Olympic Marathon, clocking 2:20:26 for a respectable 9th place.

World Records Galore

Clarke continued racing after the Olympics in the down-under track season. He was soon running world records. First he broke Halberg’s Three Miles world record with 13:07.6 and then in the new year he broke Kuts’s 5,000 WR by just 0.4 with 13:34.6. In New Zealand he improved this to 13:33.6 with relative ease--“A new world record achieved purely through trying to engineer an easy race!” (TUM, p.124) It was a busy season for him, and he even did a quick USA tour.

But Clarke’s focus for 1965 was a world tour, and he prepared for it thoroughly because he still had a lot to prove: “My intention was to answer overseas criticism that I had achieved all my records in Australia or New Zealand, where I had some sort of home-ground advantage.” (TUM, p.128) He also wanted to answer the “hurtful” criticism that he couldn’t compete in the big races.

After some very complicated arrangements to ensure his amateur status remained intact, Clarke began with an 8:32 victory over 2 Miles in California, a PB. Then in a 5,000 race in Los Angeles that both Billy Mills and Bob Schul avoided, he ran a world record for 5,000. His new mark of 13:25.8 was a huge 7.8 seconds faster than his previous world record set in Auckland. He also broke the world record for 3 Miles with 13:00.4. Then before going off to Europe, he ran another fast 3 Miles in Chicago (13:03.4), this time beating Mills.

Racing Jazy and Keino

After two races in Finland under poor conditions, Clarke went to France to meet Michel Jazy over 2 miles, which was the Frenchman’s best distance. The idea was to attack Bob Schul’s world record of 8:26.4. The two runners worked together for six laps, alternating the lead through 2:03 and 4:11. With 880 to go, Jazy surprised Clarke with a burst; the race was on. Jazy opened up a 12-yard gap with a 61.1 lap and held on for the victory, 8:22.6 to 8:24.8. Clarke later wrote, “I had not believed I could run that fast.” (TUM, p.140)

|

| World Games 5,000, 1965.Trying to break Jazy and Keino. |

After his WR, Jazy agreed to race Clarke over 5,000 in the World Games in Helsinki. The two were up against Kip Keino from Kenya, Britons Bruce Tulloh and Mike Wiggs, Americans Billy Mills and Bob Schul, and Bill Baillie of New Zealand. A stellar field. Clarke’s plan was to lead with a fast pace and then try to shake off the field with a mid-race surge. He was surprised that Jazy helped with the pacemaking—“an extremely generous gesture .” Clarke still surged in the 7th lap, and only Jazy and Keino could stay with him. He passed 3,000 in 8:05. Two surges on the next two laps had no effect. So he tried unsuccessfully to get Jazy to lead. On the last lap both runners passed him, Jazy (13:27.6) winning from Keino (13:28.2). Clarke (13:29.4) had again experienced the vulnerability of the front runner.

In a return match two days later, Keino again beat Clarke 13:26.5 to 13:29.0. Then four days after that the two were in Stockholm for yet another 5,000. Keino, having been so close to the 5,000 WR, wanted to go for Clarke’s record, and he went straight into the lead. Clarke went along for the ride. He waited till just before 3 miles, where Keino had arranged some timekeepers. Keino held him off, but then was unable to answer Clarke’s sprint to the 5,000 tape. Clarke himself was only 0.6 outside his own world record, and he showed that he could win from behind.

World Records Continue

Then buoyed by a fast win over 3,000 in Oslo (7:54.6) Clarke went to London to run the AAA 3 Miles. It was a race Clarke really wanted to win. It soon became clear with laps of 62, 65 and 64 that his only real competition was American Gerry Lindgren. The two went through the Mile in 4:15.4. The pace evened out in the next mile as Clarke ran 65s to pass 2 miles in 8:36.4, well inside world-record pace. After a ninth lap of 66.4, Clarke put in his fastest surge, and Lindgren was broken with 64 lap that followed. Clarke now saw that he was on pace for breaking the 13:00 barrier. The 16,000 crowd was going wild as Clarke was running so much faster than anyone had done before. He dug deep with 64.6 and then 61 laps for an incredible breakthrough time of 12:52.4—eight seconds faster than his previous WR. Mel Watman of Athletics Weekly called Clarke’s performance “the most prodigious in the long history of track running.” (Athletics Weekly, Aug. 29, 1965, p.17)

The next stop was Oslo to attack the 10,000 WR. In windy conditions, Clarke led from the start, cruised through 5,000 in 13:45. Encouraged by the chanting crowd, Clarke ploughed on. At about the 19th lap he had a bad patch and was tempted to drop out, but the crowd’s chanting kept him going. Then he felt better and ran past 6 Miles in 26:47.0 and 10,000 in 27:39.4 for two world records. He had beaten these marks by 24.6 and 34.6 respectively.

Since leaving Australia, Clarke had broken 12 WRs in 16 races. And he had broken through three barriers: 13:00 for Three Miles, 27:00 for Six Miles and 28:00 for 10,000. With such credentials, he could claim to be number one in the world, but his competitive record, for which he had been regularly and sometimes cruelly criticized, was still in question. The only way to answer his critics was to win gold in the next Olympics. But alas, the next Olympics were to be in Mexico City at the really high altitude of 2240 meters or 7,349 feet, where there was 5% less oxygen. The effect on unacclimatised distance runners was expected to be catastrophic; Dr. Roger Bannister said some athletes might endanger their health. And Clarke was to prove his point.

Getting Ready for Mexico City

A very concerned Clarke flew with his to Mexico City in October 1965 to research the issue of altitude competition. Competing in a 5,000 he could manage only 14:40. Afterwards he suffered from pain in his eyes and ears and from palpitations; as well, his face was grey. Fortunately, there were no long-term effects from this race, though he did find his haemoglobin was down 16% when he returned home. His conclusion was that athletes who could acclimatize at altitude before the Olympics would have a significant advantage.

As Clarke prepared for Mexico, he began to race more over the shorter 2 Miles/3,000 distance. Clearly he was working more on his speed with the aim of being able to match the last-lap speed of his rivals. In 1965 his best 2 Miles was 8:24.8; by 1968 it was 8:19.6. In 1965 his best 3,000 was 7:54.6; by 1968 it was 7:48.4. Meanwhile he improved only his 1965 5,000 time in 1966, while his 10,000 PB was never improved.

In 1966, he managed to lower the 5,000 WR, which had been taken from him by Keino, from 13:24.2 to 13:16.6, a major reduction. As well, he ran the fastest 10,000 of the year with a 27:54.0 clocking. On the other hand, he experienced two competitive setbacks in the Commonwealth Games in Jamaica. Naftali Temu of Kenya dropped him with a mile to go in the 6 Miles and was 150m ahead at the tape; Keino attacked Clarke with 270 to go in the 3 Miles and won with 1.8 seconds to spare—despite Clarke’s 58.4 last quarter. These two defeats only heightened Clarke’s awareness of the need to work on his speed if he was to win a major title.

Athletics Weekly acknowledged his improved speed the next year when he won a 5,000 race with a 5:10 last 2,000 and when he outsprinted Harald Norpoth in a fast 2 Miles (8:25.4). As well, he had the fastest 5,000 of the year with a huge 16-second margin. Significantly, he avoided the 10,000.

His pre-Olympic racing in 1968 gave him the confidence to assert that he was running better than in any time in his career. He lowered his 2 Miles world record by 0.2 with an 8:19.6, and then he ran a fine 10,000 in 27:49.4, just ten seconds off his world record. As this race was run in very windy conditions, many believed his time was superior to his world record. And although not running faster than 13:27.8 for 5,000, he had six of the top nine times for the year. Taking five months off work to train for five months at altitude in France and the US, he had done everything he could to prepare himself to win an Olympic gold in Mexico City. But the harsh fact remained that even this amount of altitude training would not put him on a level playing field with those who lived permanently at altitude.

Mexico Olympics

In the Olympic 10,000 final, Clarke was still in the pack on the 22nd lap when Wolde of Ethiopia upped the tempo from 71-73 laps to a 68.4 lap. He stayed in contact for a 69.0 lap, but Temu then injected a 64.4 penultimate lap that broke Clarke. He finished in sixth, 17.4 seconds behind the winner Temu. After the race he needed oxygen, for he collapsed and was unconscious for ten minutes. He recalled: “I just had a lap to go then, but I was really suffering…I went from running as easily as I've ever had in my life to suddenly suffering in virtually just 200 metres - the straight seemed to take forever. I just remember people passing me. I remember the tape…and I just couldn't get there. [I] was just crawling to it. I think it was about a 95-second lap and I was running, what, 68 second laps or 66 second laps so it was about 30 seconds slower and it must have all have been in that last 200 metres.” (Australian Network.com)

Still, he was back for the 5,000 final and even led after the first slow lap of 72, to take the field through 1,600 in 4:32.7. Clarke was in the hunt when the speed picked up on the 9th lap (65.8). He then took the lead, but his tenth lap was only 67. Now Keino and Gammoudi took over. Clarke fell back to fifth, but he managed a last lap of around 61 to hold his fifth position. As well, he didn’t collapse at the end.

Many would have given up after that cruel experience. He was clearly the best distance runner in the world, but his big chance to show his competitive ability had been foiled by the quirky IOC choice of a ridiculously high-altitude Games location. As Mel Watman wrote at the time, “He deserved a better fate.” (AW, Oct. 26, 1968) In the circumstances he had run brilliantly in Mexico City, he came away not with a medal but, as he discovered later in 1972, with a damaged heart.

Last Chance

There was still one chance to redeem himself: the 1970 Commonwealth Games in Edinburgh. So despite finding it harder to train and race well, Clarke worked towards a winning performance in Edinburgh. In 1969 he ran 13:33.8 for 5,000 and 28:03 for 10,000, ranking third and first in the world. At Edinburgh he ran his best 1970 times, but came away with only a silver medal in the 10,000 (he was fifth in the 5,000). Lachie Stewart, who beat him in the 10,000, admitted to feeling really bad about denying Clarke a long-sought gold medal. “I’m sorry I had to beat Clarke,” he said. (AW, Aug. 1, 1970)

|

After three more races in Europe, Ron Clarke retired. And two years later, during a medical test, a heart murmur was found. In 1983, after suffering from fibrillation while running, he had successful surgery to repair a faulty valve. Since his retirement from competitive running, Clarke has been a successful businessman and later became Mayor of Gold Coast, Queensland.

Conclusion

Ron Clarke has always been admired in the running community. While the popular press persisted in criticizing him for not winning gold medals, many runners have seen him as the epitome of the distance runner—the one who pushed performance to a new, barely imagined level. Words can’t describe my own feelings as I watched him at the White City in 1965 running where no man had run before, many seconds ahead of the 3-Miles WR. Although he believed that he had a good finishing kick—and had shown one successfully against the likes of Norpoth, Keino and Jazy—his conscience would not let him use this sit-and-sprint racing strategy, however advantageous it might be. “I loved testing myself more than I feared being beaten, and front running is the ultimate test,” he told Kenny Moore. ( Best Efforts, p.40) Thus Moore concluded, “Clarke was a front runner out of principle. He accepted each race as a complete test, an obligation to run himself blind.” (BE, p.40) In the running world the front runner is ultimately the hero—and Ron Clarke was the greatest front runner.

19 Comments