GEORGE YOUNG PROFILE

1937 - 2022

|

American middle-distance runner George Young will be remembered most of all for establishing American steeplechasing on the international map, for solidifying the 1952 gold-medal achievement of Horace Ashenfelter. Young placed fifth and third in the 1964 and 1968 Olympic Steeplechase finals and set an American record of 8:30.4. He will also be remembered for his competitive toughness. This toughness was perfectly exemplified near the end of his career (at age 36) when he had an memorable battle with 21-year-old Prefontaine in the 1972 USA Olympic Trials 5,000. Young’s ongoing reputation as a tough guy was brilliantly captured in the Prefontaine movie Without Limits. In a memorable scene (http://cdn1.anyclip.com/BTCO2tntJhYbu.mp4), Donald Sutherland, playing Coach Bill Bowerman, visits Prefontaine (Billy Crudup) to announce with great gravity: “George Young is in town.” This echoes a classic line in many western movies when locals learn that a famous gunfighter has arrived in town. George Young was indeed a “famous gunfighter” on the American track scene in the 1960s and early 1970s.

--

Although he was on the Western High School track team (as a relay runner with a 53-second quarter-mile and a 4:40 Mile to his name), George Young didn’t show enough talent to earn a university track scholarship. Nevertheless, he decided to enroll at the University of Arizona, planning to work part-time to pay the bills. After obtaining a dishwashing job by joining a fraternity, he found he had to run in an intermural cross-country race as part of his fraternity pledge. “I was in good condition,” he told Gary Cohen in 2008, “because my family lived out of town and if I wanted to get to town I had to walk or run. So I ran [the race] in my old Converse basketball shoes.” (garycohenrunning.com) Young won and was immediately signed up by Coach Carl Cooper for the university cross-country team.

There’s a widespread but incorrect belief that Young lacked natural running ability. This belief was encouraged by his high-school coach, who once said, “God didn’t give George a lot of natural ability. What he achieved was done with sheer determination and guts.” This was quoted in Frank Dolson’s biography of George Young, Always Young, but only to set the record straight. Dolson goes on to quote Walt Goodwin, who was Arizona’s top runner when Young joined the team: “First, George is built, muscled in all the right places and strong as a bull. Second, George could run a 53-second 440 in high school…. Admittedly George is the hardest of workers, but he didn’t start with nothing. He had a lot of natural ability to begin with.” (Dolson, pp. 19-20)

|

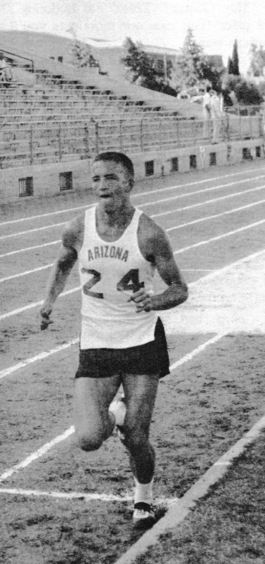

| Training as a college athlete. |

Young ran a 9:52 Two Miles in his freshman year and continued to improve slowly. In his senior year he was unbeaten, clocking 4:11 and 9:11 for the Mile and Two Miles. “I was not running all that fast; I could just outkick everyone,” he recalled. However, in his senior year he was not eligible to run the NCAAs because he had competed in his freshman year. Coach Cooper felt bad about this and fund-raised enough money to send him to the AAUs. He was entered in the Steeplechase: “I didn’t know what that was. Coach Cooper explained it to me, and we started working over some hay bales and then some hurdles.”

Baptism by Fire

So George Young went to the 1959 US national championships in Denver to compete in an event he had never run before. He has described himself at this time as “a little country hick boy about half-scared.” (azcentral.com, 2008) “I was really nervous about it,” he admits, “because I didn’t feel I belonged in that category of runners—all those great runners I’d read about in Sports Illustrated. I was embarrassed to even go into the cafeteria to eat.”

Of course, Young was no match for Steeplechase specialist Phil Coleman, who won the AAU title by 16 seconds, but he did find himself in a race for second. “With three or four laps to go, I didn’t know what place I was in. Maxie Truex--I had run against him once-- was on the side of the track and he called me by name, “George, you’re in sixth place. I got all excited and ended up in second place.” Track & Field News reported the race thus: “At six laps [Deacon Jones in second] had a 15-yard lead on surprising George Young of Arizona, but Young went 8 yards ahead with a lap to go. Jones came back, battling for a place in the meet against Russia, and led into the stretch. Young came up to his shoulder, Jones stumbled at the last hurdle, and Young was on the team.” 1. Coleman 9:19.3; 2. Young 9:36.7; 3. Jones 9:38.5.

“That’s how I got into the Steeplechase,” he says resignedly. “And then I couldn’t get out of it.” According to Phil Coleman, Young had been considering retirement from running when he arrived for his AAU run.

It was a fairytale scenario. A 21-year-old student from an Arizona farm community was now on the US team to compete in the high-profile dual meet against the USSR, having competed only once in the Steeplechase. “What the heck did I do?” he said to himself when he learned he was on the team. Young virtually matched his AAU time (9:36.9) in the USSR match and earned a valuable point, but he was hopelessly outclassed by the Russians Rzhishchin and Yevdokimov, who finished some 45 seconds ahead of him. “He really didn't have a chance. He simply didn't know the event at all,” said team-mate Phil Coleman, who finished third behind the Russians. (Track and Field News, Discussion: George Young Earlier Days, 14 Oct. 2005) Although he was now technically an international, Young clearly wasn’t yet international class. But within a year he would be. The humiliating experience became a motivator. “I got beat real bad,” he recalled later. “And that’s when I started to train hard. I knew I could whip them.” (Washington Post, 25 Feb., 1968)

Military

So how did he improve from 9:36 to 8:50.6 in the next year? And how did he improve to the point where he almost qualified for the 1960 Olympic Steeplechase final? “I never gave myself credit for that,” Young admits. “I just thought I was fortunate to be there. I could not imagine myself as being world-class. Fortunately [after the USSR match] I went to officer school at Fort Benning, Georgia. Colonel Don Hull , who later became head of AAU America was head of Army Special Services. He had been at the meet in Denver and knew I was going into the service. As soon as I got to Fort Benning, I had orders to got to Fort Lee, Virginia, to train for the Rome Olympics.”

At Fort Lee, Lt. Young teamed up with Deacon Jones and trained with him through the winter. In the big Olympic-year Services meet early in the 1960 summer, Young won in 9:09.8, earning a place in the Olympic trials. But before those trials he was outclassed by Coleman and Jones in the Compton meet and in the AAU, where he finished fourth in 9:08.1, some 12 seconds back.

Rome Olympics

Young’s chances for an Olympic berth did not look good. He was ranked only 11th out of 12 for the trials. “I had just finished infantry training,” he recalls. “I figured this was my last race. I convinced myself before the race that afterward I was going to Korea so I might as well run the best race I could.” (garycohenrunning.com) His plan was simple: “I decided to try to be in 4th at halfway. And then outkick somebody to get 3rd.” And with one lap to go (7:44.5), he was indeed 4th behind Tom Oakley. In the last lap he passed Oakley on the back straight and then took Coleman at the water jump. Jones was now only four yards ahead and Young passed him coming into the straight. He had won the Olympic trials with a meet record and had improved his PB by 16.7 seconds. 1. Young 8:50.6; 2. Coleman 8:51.03; 3. Jones 8:52.5.

So in just over a year Young had developed from a Steeplechase novice into a true international. But confidence was still a problem: “I still didn’t recognize that I was that good a runner.” Despite being “just scared to death in Rome,” he acquitted himself really well in his Olympic heat, staying with the leaders until he fell with three laps to go. ”It was really sad,” he says. “I was in good shape in the race. I hit a hurdle ands went sliding across the track. I was skinned up bad. I gathered myself up and took off, but I got edged out by the Russian runner. I just couldn’t quite get past him. I could have qualified for the final and I might have been right in there for a medal.” There is no doubt that Young was in good form: despite his fall, he still ran within 0.2 of his PB. 1. Krzyszkowiak 8:49.6; 2. Muller 8:49.6; 3. Konov 8:50.0; 4. Young 8:50.8.

Post Olympics

It was back to work after a European tour where he ran several races, including an 8:53.6 Steeplechase (3rd) and a 4:06.2 Mile (3rd). But special time for training was only granted by the military during Olympic years, so Young now had to train in his lunch break. He did manage to get some cross-country and indoor competition to round out a good winter’s preparation. His season started off modestly with a 9:18.3 win in the Quantico Relays and another at the Chicago Relays (8:57.2). But in the AAU he was convincingly beaten by Deacon Jones. He led a lot during the race, but Jones was too strong for him and he had to fight to get past Bob Schul, who had overtaken him on the last curve. Still his time, the same as in Rome, was encouraging. 1. Jones 8:48.0; 2. Young 8:50.8; 3. Schul 8:53.6.

Again, his second place put him in the USA team for the USSR dual meet. This time it was in Moscow and under USSR “rules.” It can’t have been an accident that the bell didn’t sound for the last lap of the Steeplechase--after the lap times had been given only in Russian. This failure to announce the last lap was Young’s undoing. After a brisk 2:51 first K (8:33 pace), Young let Sokolov go at the halfway point. But he kept the Russian within striking distance. He felt ready to attack the Russian on what he thought was the penultimate lap: “We came round the last corner and I was feeling pretty strong and was just going to edge up on him…and the race was over.” Sokolov, who understood the lap times, knew he was on the last lap; Young didn’t. So Young finished the race with a lot left. Nevertheless, his 8:38.0 was a huge 12.6-second improvement; this time ranked him 6th in the world for 1961. Had he been given the courtesy of a bell, he would surely have been several seconds faster. 1. Sokolov 8:35.4; 2. Young 8:38.0; 3. Naroditsky 8:56.0.

Young continued competing in Europe after this fine run. First, he ran for his country in two more dual meets. He won a close race in London with an 8:47.0 clocking (2. Jones 8:47.3; 3. Herriot, GB 8:47.6). He was second in Poland with an 8:48.8 behind Krzyszkowiak (8:32.6). And finally, in an open meet in Berlin he was third in 8:50.2 behind Jones (8:42.4) and Roelants (8:43.2). Although his win in London was a great achievement, these post-Moscow performances showed he was tired after a long competitive season.

1962

|

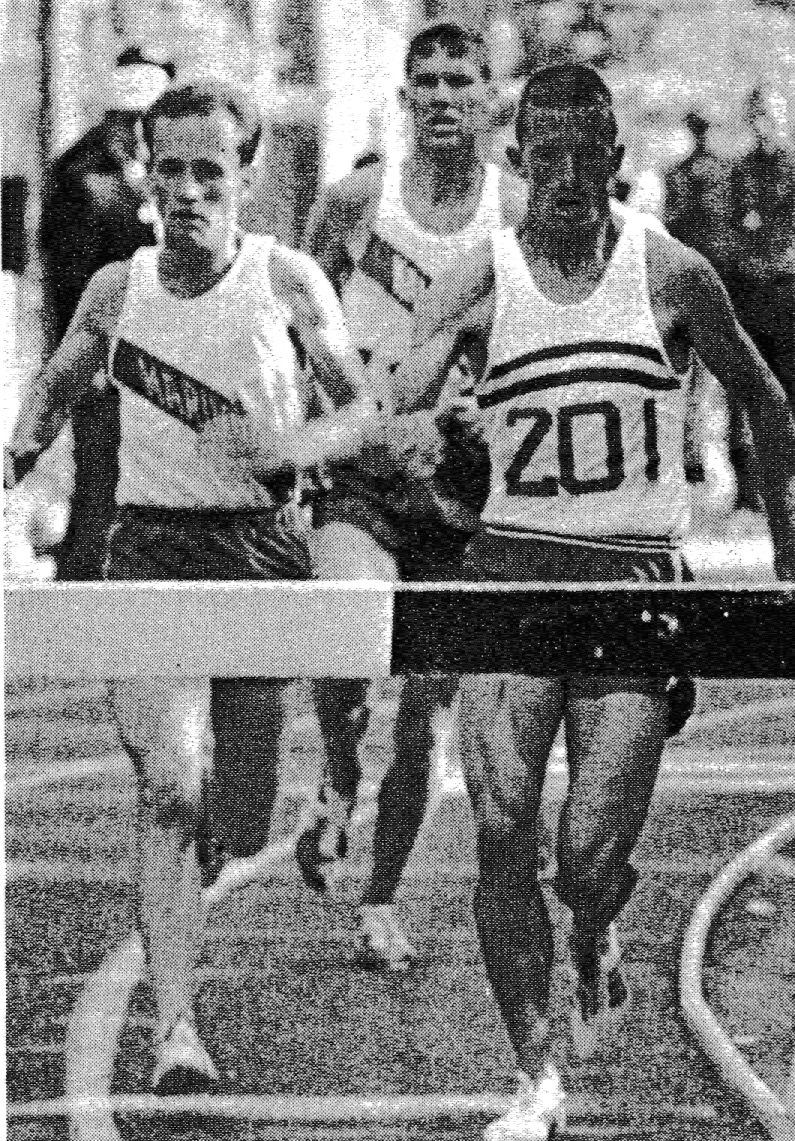

| Young's first AAU Steeplechase win. |

After two comfortable early-season wins--9:16.9 at the Coliseum Relays and 8:52.2 at Walnut--Young finally won his first AAU title in 1962. After Pat Traynor set the pace, Young took over on the sixth lap with four runners at his heels. On the seventh lap he began to pull away and led by 15 yards with half a lap to go. He increased this to 25 yards at the tape. He said that he just followed the early pace as he didn’t know what shape he was in. “It was a good pace, and after I took the lead, I felt strong. I believe I could have done 8:40 if necessary.” (Track & Field News, July 1962) 1. Young 8:48.2; 2. Foreman 8:52.2; 3. Traynor 8:56.8.

This AAU win qualified him for meets against Poland and Russia. He again came up against the Olympic champion Krzyszkowiak in the Poland match. On the last lap Young tried to pass the Pole on the inside, and the two runners collided. Krzyszkowiak came out best and went ahead to win 8:38.0 to 8:42.4. Clearly Young was rounding into top shape, and he looked even better in the USSR match. Young was in third place with two laps to go when he decided to chase down the leading Sokolov. After moving into second place, however, he fell: “My trailing foot caught on the hurdle,” he recalled. “The damage was mostly in breaking my stride and sapping my energy getting back up.” (Track & Field News, August 1962) After this fall, Young tried to catch the leader, but he could only close the gap a little. 1. Sokolov 8:42.3; 2. Young 8:44.7. This July race was the last of his season; Young did not go to Europe.

Bleeding Ulcer

1962 was the first year Young had not improved his times. He had as usual run well competitively and had won his first AAU title. But the year was a transitional one as he moved from the military to life as a citizen selling insurance. It was perhaps the stress of this major change in his life that caused Young to develop a bleeding ulcer. Not surprisingly this drastically affected his training and general health. Still he managed to be fit enough to go to Sao Paulo in April, 1963, for the Pan-Ams. Once there he developed pneumonia and couldn’t compete. But there was a plus to this setback: the antibiotics he was given for pneumonia also cured his ulcer.

He was thus able to compete in the 1963 American track season, though at a very reduced level. He could only manage 8:58.6 for a season’s best. There was time for only three weeks’ training before the AAUs. And because he wasn’t sent his air ticket until two days before the race, he had to run after travelling from Arizona overnight. In the circumstances he did well to finish fourth in 9:02.9. Finally healthy, he was able to look forward to a good winter’s training in preparation for the Tokyo Olympics. He would have noted that his main rival in Tokyo, Gaston Roelants, had just broken the 8:30 barrier with 8:29.6.

Olympic Build-up

Young did not compete much in the 1964 indoor season. He didn’t run in any California meets and had just one race in Philadelphia (5th in a 2 Miles with 8:56.6). He was not in great form early in the competitive season, but gradually improved over the summer. There were two reasons for his early mediocre form: first he was dealing with an illness; second he had a sore back. An early Steeplechase win at the Mt. Sac Relays (8:47.4) was promising, but he then lost three major Steeplechases to Jeff Fishback. The first time was at Compton, where the race was 70yds short. He lost to Fishback again in the AAUs . After pushing the pace after five laps, he was caught by Fishback at the last water jump and watched him power away to a large lead. 1. Fishback 8:43.6; 2. Young 8:49.4. His third loss to Fishback was in the Olympic Trials (8:40.4 to 8:45.8) when he was unable to hold on to Fishback after five laps.

At least Young was getting faster in each of these races against Fishback. He was said to be training four hours a day in the early summer. As it turned out, Fishback ran his best 1964 races in the early summer, well before the October Olympics. In late July in the dual meet against the USSR, Young looked much better and achieved one of his longtime goals—to beat the Russians. “I was really up for the Russians,” he said at the time. (Track Newsletter, 17 Sept. 1964) According to his plan, he stayed with the Russians for six laps before making his move. Neither Russian was able to respond and he was comfortably clear at the tape. 1. Young 8:42.1; 2. Fishback 8:43.6; 3. Osipov 8:44.

“I wasn’t interested in the time at all,” he told Frank Dolson. “I was interested in beating the Russians, and I think that’s all the crowd and the country and everybody else was interested in. I felt I really achieved something—something I’d pointed for since 1959. It took me five years to accomplish it, and it made me feel good that I had stayed with it long enough.” (p. 75)

Young beat Fishback again in the Final Olympic Trials on September 13. 1. Young 8:44.2; 2 Zwolak 8:46.2; 3. Fishback 8:55.8. “I felt very tired, a real hard race for me,” he told Track & Field News. “There is just too much pressure in a race like this.” (Sept. 1964)

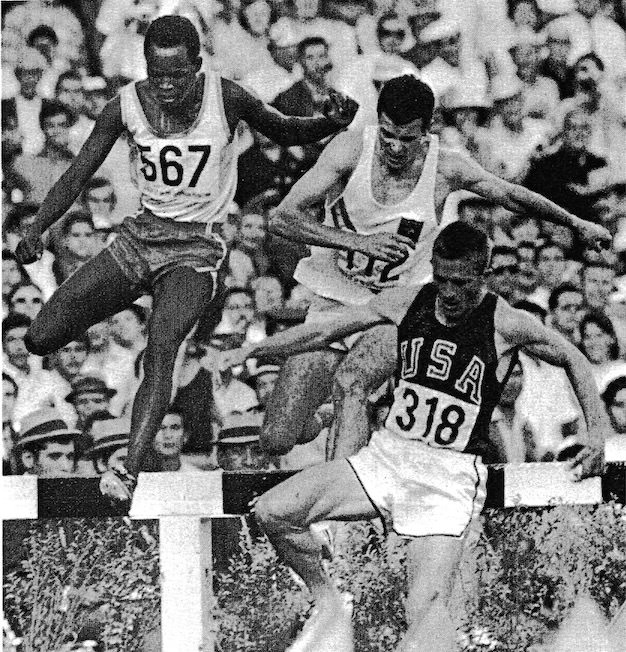

1964 Olympic Steeple

So Young was clearly rounding into top form when he left for Tokyo. He had only the 15th fastest time, but most commentators expected him to make the final. Roelants was such a clear pre-Games favorite that Young decided he should race for second place in the final. The three heats saw Herriott emerge as another favorite with 8:33; Young finished third behind him in 8:34.2—the fifth fastest heat time and a 3.8-second PB.

|

|

Early in the Tokyo final ,Young at the back of the field. |

In the final, Roelants went to the front before the end of the first lap. He was followed closely by the whole field, with Young at the very back. The Belgian made his move just before 1200; only Texereau tried to go with him. At 2,000, Roelants led Texereau by 15yds. Young, feeling good and seeing the race get away from him, moved up quickly on the fifth lap to third, just 5yds behind Texereau. Apart from Roelants and Texereau, Young had run the fastest second K (2:48.4—8:25 pace). On the sixth lap he moved into second, but he was still 40 yards behind Roelants. His effort in the second K began to tell: Herriott caught Young at the bell and passed him with 200 to go. The tiring Young could not hold on to Herriott and was passed at the last water jump by Belyayev of the USSR and Oliveira of Portugal. All he could do was to hold on to fifth in 8:38.2. 1, Roelants 8:30.8; 2. Herriott 8:32.4; 3. Belyayev 8:33.8; 4. Oliveira 8:36.2; 5. Young 8:38.2.

There might have been a reason why Young abandoned his pre-race plan to go for silver. He had entered the race inspired by the 10,000 win by his good friend Billy Mills a few minutes earlier. Perhaps the elation led to his reckless move in the second K: “It was one of the stupidest races I ran in my life,” he admits. “I just felt super and I took off after Roelants way too hard. That killed me at the end. I got passed by three runners, including Maurice Herriott, who I had never lost to.” Despite Young’s self-criticism, it is fair to say that he still ran really well for someone ranked 15th among the entrants. Dick Drake in Track & Field News called his performance in Tokyo “remarkable.” (November, 1964)

1965

Still not satisfied that he had achieved his potential, Young went back to Arizona for another winter’s conditioning. He was now working as a high-school science teacher. His job enabled him to compete regularly in the 1965 indoor season. Using his kick he won a string of 2 Mile races, defeating Billy Mills, Gerry Lindgren (twice), and Bill Baillie. Only at the end of the season did he lose races to Baillie and Ron Clarke. His best two-mile time was 8:41.4. It had been an encouraging season and had kept him interested in running. “The indoor season gives you some purpose,” he says.

Outdoors he ran 8:51 and 8:41 steeplechases before winning the AAU title in a chaotic race in which the lap times were called out half a minute wrong. As he prepared for three major dual meets in August, he claimed he would be able to run in the 8:30s. But this never happened. In the USSR meet he was frankly outclassed by Kudinsky, finishing third in 8:44.8, 13 seconds behind the Russian. Against Poland a week later he was beaten by Szklarczyk, 8:48.8 to 8:50.6. His only win was against West Germany, when he defeated Lezerich 8:41.8 to 8:43.0.

1966

The 1965 outdoor season had seen Young still running at international level, but he hadn’t really progressed. His times were slower than his 1964 marks, and his competitive record was not as good as in previous years. So he decided to stop steeplechasing and run flat races. “I was a pretty good flat runner,” he asserts.

He had never been totally happy as a steeplechaser: “I would have been running the 5,000 all the time, if someone had been coaching me full-time after I got out of college. I’m not that good a hurdler. I’m only 5ft-9 and my legs are not very long. I felt I had a disadvantage to begin with.”

This was a big decision. Young says he switched partly because of his disappointment in Tokyo. He had also developed a taste for flat races from competing indoors: “I got to running 2 miles indoor, which was really made for me with the turns. Indoor running was exciting and fun; I really enjoyed that.” There was a third reason: “I switched because nobody cares about the steeplechase. I could break the world record, and I would not even get my name in the papers. And besides, I haven’t had the chance to work on the Steeplechase this year.” (Track & Field News July 1966) Some bitterness about the event is evident in a comment he made in 1966: “The Steeplechase is for peasants.” (Track Newsletter, 30 June 1966)

Before embarking on his outdoor season, and despite easing up on his 100-mile a week regimen--“I’ve cut down my training to six miles a day five days a week,” he was quoted as saying in February” Track Newsletter, 10 Feb. 1966)--Young raced 2 Miles indoors a couple of times. In Philadelphia he beat Bill Baillie (8:50.0 to 8: 53.2), but then lost badly in New York behind Norpoth, Kudinsky, and Laris with an 8:51.4.

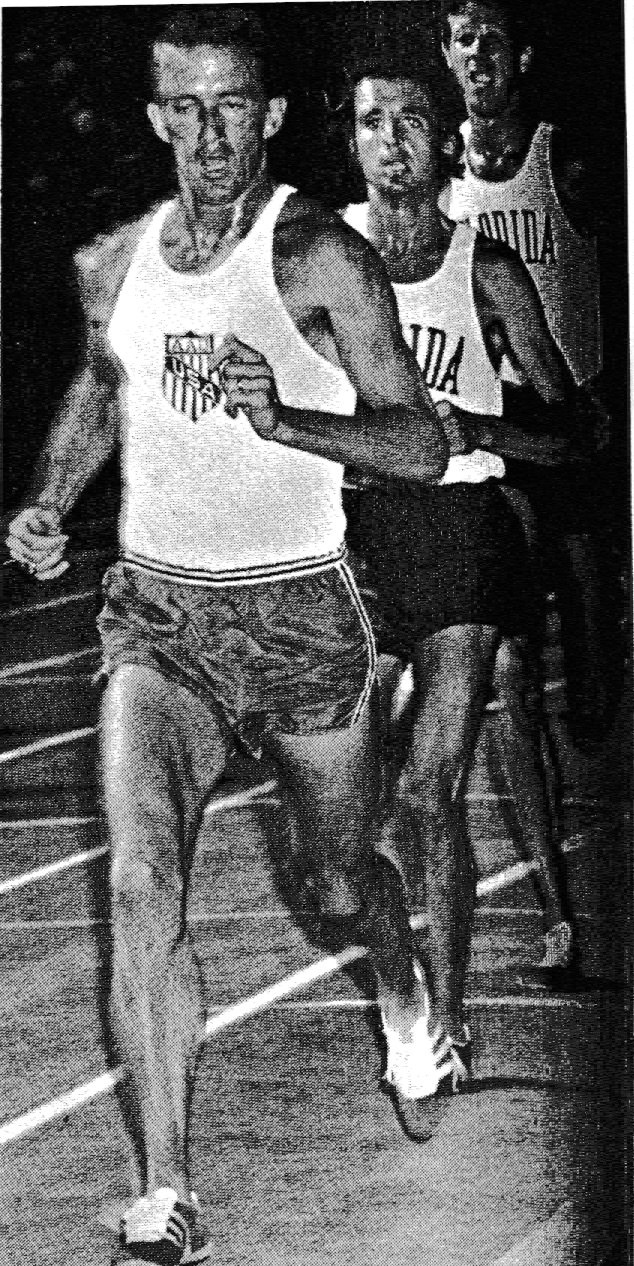

|

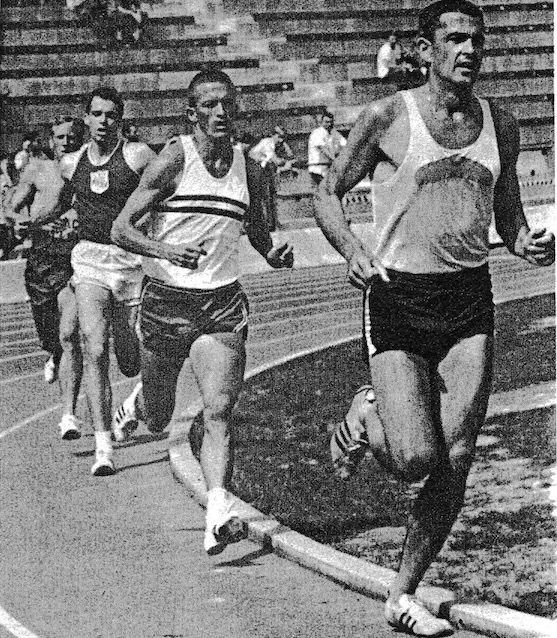

| On his way to a win over Clarke |

His first year outdoors as a flat runner was a disappointment even though he won the AAU 3 Miles and won a major 5,000 in San Diego. After an early defeat over 5,000 at the hands of Jim Grelle (both timed in 14:10.8), he had wins over 2 Miles (8:59.2) and 3 miles (13:49.0). Then on June 11 he ran his best race of the season. In a 5,000 he was up against some of the best runners in the world, Ron Clarke, Gaston Roelants, Billy Mills, and Tracy Smith. It should be pointed out however that Clarke had gone 40 hours without sleep, Mills had only been training for ten weeks after a long lay-off, and Roelants ran with a bandaged thigh. After a brisk 4:22 first mile, the race slowed, and 100m before the bell there were six runners together. Young swung wide and was in the lead when the gun fired. He ran the last lap in 56.9 with Clarke desperately trying to catch him. 1.Young 13:40.2; 2. Clarke 13:40.6; 3. Smith 13:42.2; 4. Mills 13:44.6; 5. Roelants 13:46.2. After the race Young was reported as saying he was pleasantly surprised as he was concerned about his conditioning and lacked confidence.” (Track Newsletter, 16 June 1966)

|

|

A close win from Tracy Smith in the 1966 AAU 3 Miles |

Two weeks later, Young won the AAU 3 Miles. He stayed in the leading quartet for most of the race (with Smith, Van Nelson, and Laris). Laris went at 220, but Young and Smith passed him coming out of the bend. The two were neck-and-neck all the way, with Young just getting ahead. 1. Young 13:27.4; 2. Smith 13:27.4; 3. Laris 13:28.4.

The San Diego 5,000 and the AAU 3 Miles were good wins that underlined what a great competitor he was. These two races were the highpoint of his 1966 season. But his times were well behind the world leaders. His excellent 13:40.2 was 24 seconds slower than Ron Clarke’s new WR. Clearly he was not as close to the world’s best on the flat as he had been in the Steeplechase.

Three races in July showed Young’s form was in decline. First, he was beaten into third in a 3,000 (8:05.0) by Grelle and Traynor. Two weeks later he had a poor run in the All-American Invitational at Berkeley: 1. Smith 13:42.0; 2. Mills 13:52.6; 3. Young 14:01.2. And a week later he was well beaten in the LA Invitational by Clarke (13:28.4) and Smith (13:40.2) when he could manage only 13:52.

New Approach

A mediocre abbreviated indoor season in 1967 with a best 2 Miles of 8:45.8 and with 2nd 3rd and 4th placings further suggested that his running was not going in the right direction. It was time for a rethink.

Young didn’t compete outdoors in 1967, but he did make a big decision about his training. He decided to get himself a coach. Although he had been guided by Carl Cooper in his early career, Young had been on his own for years—he had no coach and generally trained alone. For a while before the 1964 Olympics he had trained with Bob Schul. “Training with Bob was good,” he told Gary Cohen, “as I had been training in the desert basically all by myself…. I took some of his ideas in training and utilized the ideas from the other coaches and athletes I had trained with.” (garycohenrunning.com) Still, Young admits that up to 1967 he was training incorrectly. He realised that he needed a coach to help organize his workouts.

His choice was Jim Fox, who worked as a math teacher in his hometown of Silver City, New Mexico. Fox had previously been the track coach at Western New Mexico University. “I told him that I had been on two Olympic teams but was not satisfied with my training. I used to go out really hard and puke, feel good about it and then feel shot the next day. I told Jim that I needed him to get my workouts under control until the 68 Games.” They started working together in the fall of 1967: “We did a progression of continually harder and harder fast workouts all the way through to the Olympics. The track workouts were done at least 3-4 times a week. I did a 7 ½ mile loop every morning. Once a week I’d do a longer run.”

1968

|

| Beating Smith in the 1968 indoor season. |

Young’s more systematic training under Jim Fox soon paid dividends. He completed a series of eight undefeated races in the 1968 indoor season. He was also running fast times. The series started with a PB 2 Miles in 8:31.8 at the LA Invitational (“The best 2 Mile race I’ve ever run”) beating Smith, O’Brien and Clarke. That was followed by a 13:17.6 AAU 3 Miles win over Smith. Rather than training hard every day, Young was now tapering his training for weekend competition: “I work as usual in the early part of the week and tail off starting Wednesday. That way I find myself stronger for the race.” (Washington Post, 12 Feb. 1968)

Young continued his unbroken winning streak right through the 1968 outdoor season to the Mexico Olympics. His new training regime produced some remarkable performance that included American records in the Steeplechase and 2 Miles. Not only was he winning all his races but he was also running much faster times. He was in the best form of his life.

His summer season began with a huge win over Ron Clarke in a 2 Miles in San Diego. It was a tight race against an in-form Clarke. The two were side-by-side at the bell. And then Young pushed ahead. His last lap of 58.0 was just enough to hold off Clarke (8:22.0 to 8:22.6) Young’s time was the third fastest all-time. It was an 8-second improvement and 3.2 faster than the American record held by Grelle and Ryun. Then after winning the Steeplechase at the Compton meet in a fast 8:36.2, he went on to run a brilliant solo 8:30.6 to win another AAU title and break his own American record by 3.6 seconds. He led after two laps and was never pushed by his competitors. It looked like he could run even faster in a competitive race.

But a week later in the Olympic Pre-Trials he had a “bad” race (“I wasn’t quite up for this race.”) and had to dig deep to hold off Traynor. Despite not feeling 100%, he blew the field apart on the 5th lap; only Traynor could go with him. Young had a 6-yard advantage at the gun, but Traynor gradually closed and was very close at the tape (8:34.2 to 8:34.4).

A week later he had another tough battle, this time with Steve Stageburg over 5,000. Young used his speed over the last 300 to win in 13:38. “I had hoped to run faster, but there’s nothing wrong with 13:38,” he quipped afterwards. (Track & Field News, July 1968)

Pre-Olympic Races

Young surprised a lot of people with his next race—the US Olympic Marathon Trial. The race was held at 7,400ft in Alamosa, Colorado. Confident in his ability to deal with the altitude, he ran carefully. He was fifth after the first 5.2 mile loop, 1:10 back. He was sixth after the next lap, 1:20 back. One the next lap he moved up to 4th, 1:30 back. With a lap to go he was in second, 1:14 back of Kenny Moore. Young didn’t speed up but he still managed to catch Moore and put a whole minute between them by the finish (2:30.48). It was his first attempt at a Marathon. His splits for the five laps show how consistently he ran: 29:23, 29:55, 31:08, 29:11, 30:31. He was now on the Olympic team, and with 23 days to recover, he still had to qualify in the Steeplechase.

That qualification was achieved relatively easily. Young took charge from the start and was never out of the lead, but Bill Reilly came close to catching him, finishing only one second behind (8:57.8 to 8:58.8). Still unbeaten in 1968, George Young was on his way to Mexico.

Mexico

|

|

The last water jump: Young leads from O'Brien with Kogo about to pass them both. |

Young went to Mexico City with the fifth fastest time in 1968. Ahead of him were Roelants, the former WR holder (8:29.2); Kuha of Finland, the new WR holder (8:24.2) and two Russians Kudinsky and Naroditsky. Another Russian, Morozov, had run exactly the same time as Young (8:30.6). Just slower than him was the Aussie O’Brien (8:31.0). Also competing was the Kenyan Kogo, who had run 8:31.6 in 1967.

Young had a lot going for him. He always performed well in big races and was unbeaten in 1968. Only Roelants matched him for experience. As well, he was used to altitude. The seven Track & Field News experts also believed he had a good chance: three put him first, three put him second, and one put him fifth.

The heats had a few surprises, though not for Young. He qualified comfortably. Kuha was ill and didn’t start. The main talking point was the way Amos Biwott (listed PB 8:44.8) won his heat 11 seconds faster than anyone else, after a first K at 8:15 pace.

In the final, Young started off conservatively at the back, letting the other runners jockey for early positions. After three laps he had moved up to 6th. At 2k he was in seventh. But when the bell rang he was up at the front behind Kogo. Roelants, O’Brien and Morozov were still in the race. On the backstretch Young attacked, O’Brien went with him and Kogo dropped to third. Well behind the leaders, Biwott was charging through the field.

Young landed first at the water jump with O’Brien just behind him. Kogo, who was coming up fast, overtook both of them as they left the water. Behind them Biwott had a spectacular water jump and was closing right up. Kogo was ahead at the last hurdle, while Young and Biwott were neck and neck. O’Brien was hanging desperately on to Young.

After the last hurdle, Biwott’s amazing momentum took him to the front ahead of Kogo. Meanwhile, there was a great tussle between Young and O’Brien for third. Despite landing awkwardly at the last hurdle, the Aussie managed to get on equal terms with Young. But just before the tape Young found a little extra, and O’Brien tied up. In his great fight with O’Brien, Young almost caught Kogo at the tape. 1. Biwott 8:51.0; 2. Kogo 8:51.6; 3. Young 8:51.8; 4. O’Brien 8:52.0.

Young discussed the race with Gary Cohen 40 years later: “Looking back, maybe I should have waited longer—I don’t know—but there was a wide open space and I took it. I didn’t know if I could hold the pace all the way to the finish…. When I hit that fast pace I was hoping I could hold on and I just didn’t have quite enough to get to the finish line.” (garycohenrunning.com)

Was Young surprised when Kenyans came by? “Oh no, I wasn’t surprised. I had planned it pretty right for the conditions and the altitude. I didn’t finish as strong as I’d have liked. But I wasn’t slowing down. I didn’t have a lot of energy left. I was completely exhausted. Everything was grey at that point in time. But I recovered well; I was in fantastic condition.”

After the race Young told reporters that he thought Biwott had the ability to run under 8:20 eventually. He went on, “O’Brien and Kudinsky are both capable of doing under 8:20 right now. We’ll never know what George Young can do. I’m through with steeplechasing.” (Track & Field News, Oct./Nov. 1968)

1968 Mexico Marathon

After such an emotional final it must have been hard for Young to get up for the Olympic Marathon four days later. But up for it he was. Running conservatively as he had in his Marathon debut, he had moved up to 10th at 35K. But then disaster hit: “I hadn’t consumed enough liquids and even though I was running a pace I could handle, I got cramps in both legs from my hamstrings down to my heels. I had to hobble in due to my lack of experience and not having anyone to tell me what I needed to do. All I knew was to go out and race. The lack of experience cost me the gold medal,” (running.com, 2012) He finished 16th in 2:31.15—only 27 seconds slower than his time in the US trials.

Not Done Yet

Less than three months later, Young was back competing. His 1969 indoor season extended his indoor winning streak to 17 victories and also brought him two WRs.

He started with a fast 2 miles in 8:32.6 and the next week beat Ron Clarke in 8:42. After two more wins (8:44.6, 8:37.8), he equaled Kerry Pearce’s 8:27.2 WR. He actually ran 8:27.1 but it was rounded out to 8:27.2. This rounding-out didn’t please Young: “I’m disappointed. It’s a lot tougher running without anybody setting the pace. I’d like to have the world record. It belongs to me not him.” (Associated Press, 23 Feb. 1969)

A week later at the indoor AAUs, he announced the 3 Miles would be his last race. And what a swan song it was—an all-out attack on Ron Clarke’s indoor WR of 13:12.8. After passing one mile at 13:14 pace (4:24.7) and two miles at 13:16 pace (4:25.4), he needed to run only 2:11.4 for the last two laps. He did this easily with 2:08.4 to set a new world mark of 13:09.8. “I was going for a record all the way. And the crowd really helped. You can’t set a good record without a good crowd.” (New York Times, 2 Mar. 1969)

At home he was offered Carl Cooper’s position at the University of Arizona, but he declined, instead going to work for a vehicle transportation company in Phoenix. Less than two years later he went back to school at Northern Arizona University to study for a Ph.D.

Comeback

In August 1970 Young was back in Flagstaff, Arizona, on a fellowship. “I was not too busy with my classes,” he says, “so I started running with the cross-country team. It had been 2 ½ years [since retirement] and I had been running every so often. There were two British runners on the team, Sliney and Selby. I started running with them. They would run away from me, showing off, and a couple of times I would run them down. And I thought, ‘You know what, I haven’t lost that much.’ So I started training a little bit harder and ran a couple of races.” He started running once a day 4-5 times a week in August; in September he was training twice a day. By the end of the year he was training harder than ever.

1971

George Young’s return to indoor competition at the start of 1971 was big news. He told Track & Field News that he had no big plans although he might be racing outdoors in the summer. In a Washington Post feature, he explained why he was coming out of retirement: “It’s not for a wrist watch or for any recognition. It’s for the feeling, just the personal feeling of doing something worthwhile. Running is something I do well,, and I feel almost a responsibility to do it.” (William Gildea, “Young Feels Young Again,” 26 Jan. 1971)

He continued his indoor winning streak from 1969 (17 consecutive wins). On January 6 he beat Pearce and Shorter over 2 Miles in the LA Sunkist meet with 8:42.2 and then won

another 2 Miles in El Paso (8:56). But his winning streak came to an end on February 12. Despite running a fast 8:30.8, he was narrowly beaten by Pearce (8:30.0) and O’Brien (8:30.8). A week later in San Diego, his 8:34.6 was only good enough for 4th behind O’Brian (8:19.2), Pearce (8:20.6), and Shorter (8: 26.2). Three good times and two wins gave him the confidence to compete outdoors.

|

|

A new American 5,000 record (13:32.2) ahead of Shorter and Bacheler. |

His season started on April 24 with a 5,000 at Walnut, California. He finished second in 13:56.4 behind Norwegian Arne Kvalheim (13:52.2). Two weeks later at Fresno he got his own back on Pearce with an 8:30.5 victory over 2 Miles. Then Young shocked the running world with an American 5,000 record at Bakersfield. Shorter led for the first ten laps, taking him through 2 miles in 8:44. Young made his move early with 600 to go, but he was unable to drop Shorter and Jack Bachelor right away. Then he gradually dropped Bachelor and then Shorter to win by 2.8 seconds in 13:32.2. He was 1.6 second faster than Gerry Lindgren’s American record.

Young won another big race on June 5, a 3 Miles at Modesto: 1. Young 13:10.8; 2. Bjorkland 13: 12.2; 3. Stageburg 13:18. 8. But this was the last race of his season. His future as a runner was uncertain. He told Runner’s World (July 1971) “I don’t have any designs on Munich.” He said he was planning to take a coaching job in 1972, which would end his amateur status. Still, he kept training through the fall, and in January he was still unsure, telling the Washington Post, “[The Olympics] will certainly be a turning point in my mind for the next few months.”

Olympic Build-up

Young started competing as soon as the 1972 Indoor season began. His first two races saw him in second and third places with 8:53 clockings. But in his next two races he showed better form winning in 8:47.2 and 8:28.1.

Outdoors, his track speed was confirmed in Houston when he ran a One Mile on a new $185,000 tartan track. He became the oldest (34) runner to break the 4:00 barrier with 3:59.6.

Busy with his studies, he didn’t race much in the early track season. He won a 5,000 in April in a modest 13:55.4; in May another 5,000 in 13:37.6 earned him only a third place. But his training under Jim Fox was going well and he entered the Olympic trials after “the training month of my life.” He was ready to take on America’s new 5,000 star, Steve Prefontaine.

Young qualified comfortably for the 5,000 final in 14:11.6. Afterwards he told the New York Times, “It’s going to be tough to make it. The 5,000 is a new event for me. I don’t feel that my age and experience will mean that much. I’ve only run four or five 5,000s in my life.” (7 July 1972)

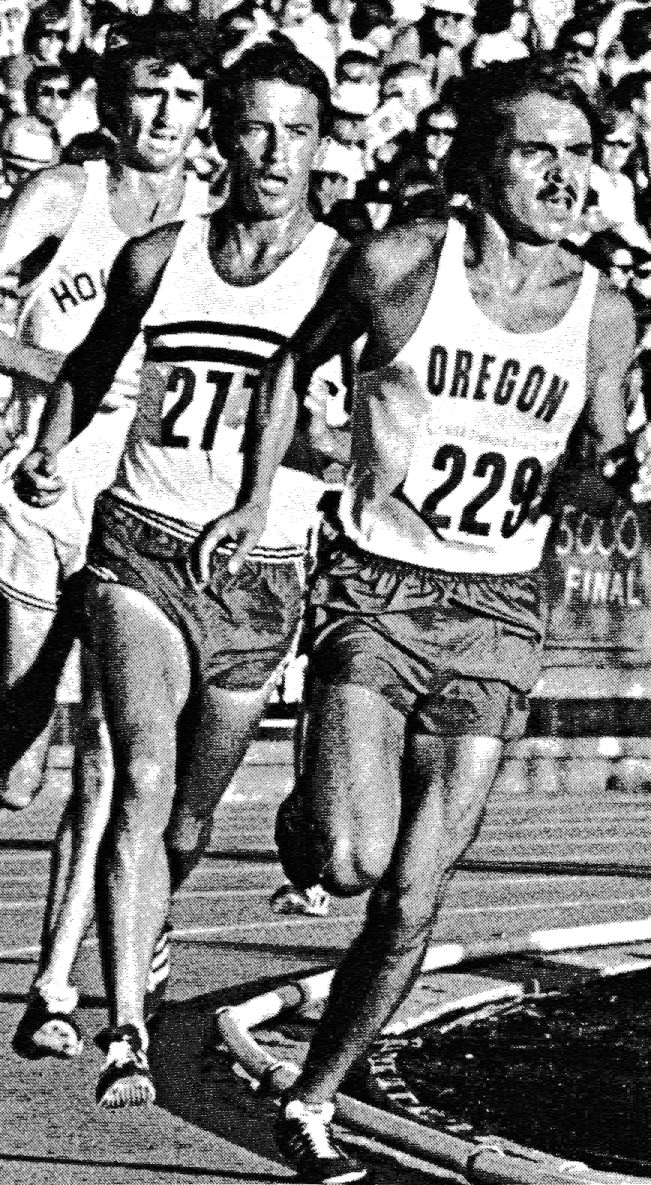

|

|

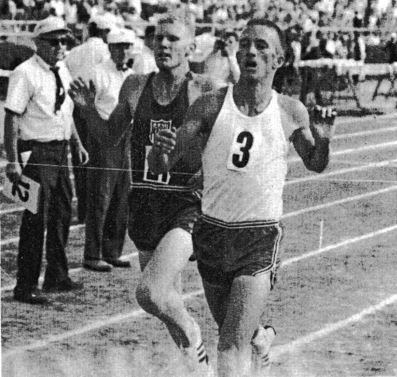

Taking on Prefontaine in the Olympic Trials. |

Still confident in his finishing kick, Young wasn’t going to do any of the early leading. He ran in the pack as Lindgren led out in 2:09.8 for the first two laps. Then Prefontaine took over. Running steadily he passed 1600 in 4:22 and 2400 in 6:36. He maintained the same speed to complete 8 laps in 8:48. With the field now strung out, only Hilton and Young were with him. Young now moved up to Prefontaine, and the race was on. Laps of 64.8 and 63.4 broke Hilton. Then Prefontaine put in a killing 61.5. that weakened Young. He was 8m behind Prefontaine 200m later at the bell. Prefontaine extended his lead to the tape. It had been a magnificent race: Prefontaine’s speed was stunning—2:00 for the last 800 and 3:03.2 for the last 1200. Young, despite being run into the ground, still managed his best time ever with 13:29.4 behind Prefontaine’s 13:22.8.

Cordner Nelson reported in Track & Field News: “Young was surprisingly unpleased with his performance: ‘I am disappointed. I should have gone faster. I need more races. I will be tougher in Munich.’” (July 1972) His determination was evident in his post-race comment to the Washington Post: “I’ve got a lot more training to do. I know one thing: I can improve a lot more than he can between now and then.” (10 July 1972) Young today still has strong feelings about the race: “I can tell you this. If I had been in the condition I was four years before, I would have kicked his ass.”

Drastic Measures

The experience of being beaten by Prefontaine drove Young back to his old training regime of just running till he dropped. Bad decision. “After the trials, I thought I had to train harder,” he admits. “I went back to Flagstaff (2130m, 7,000ft). Flagstaff has some tremendously high mountains. They have roads up to these watchtowers. It’s particularly tough, about 3 miles nearly straight up. I trained up that thing as hard as I could. Of course, you’re practically leaning over. Soon thereafter I could run forever, but if I tried to do speedwork, it hurt in my groin.”

In his desperate attempt to improve for Munich, Young had injured himself. He had improved his stamina but he couldn’t sprint. This was to be his downfall in the Munich Olympics. He was with the leaders in his 5,000heat until the pace quickened near the end of the race. He just couldn’t accelerate. 1. Viren 13:38.4; 2. Sviridov 13:38.4; 3. Jansky 13:39.2; 4. Young 13:41.2.

Once back home he was approached by a chiropractor who healed Young with one manipulation. It was a sad way to end a great career. He did compete for a while in the new pro indoor track circuit. However, running for money didn’t appeal to him, and the enjoyment of competition was no longer there. He soon quit. But he continued in the sport, coaching and eventually becoming Athletic Director at Central Arizona College. And he also continued running (for fitness) until he needed a hip replacement four years ago. Now the octogenarian walks.

Recommended Reading

Frank Dolson, Always Young. World Publications, 1975.

Gary Cohen. George Young Interview. garycohenrunning.com

9 Comments