Profile: Peter Snell

1938-2019

Few runners have made such a dramatic impact on the international scene. Peter Snell stunned the running world in 1960 when he won the Olympic 800. He had been lucky to have made the New Zealand team in the first place, and then to have got through the two elimination rounds was beyond anyone’s hopes. What was also shocking was the marathon training that helped get him to the pinnacle of his sport in such a short time. From his Olympic gold medal in Rome, Snell went on to be the dominant 800/1,500 runner of the first half of the 1960s.

|

| Snell leads the 1956 Auckland Schools Mile. He finished second. |

As a teenager, Snell was a typical all-round sportsman. He played rugby, tennis, cricket and golf. In tennis, he competed in the New Zealand Junior Championships. It wasn’t until he was 19 that he focused on running, having been inspired by the encouragement of coach Arthur Lydiard, who had seen him win an 880 handicap. Lydiard was perceptive, for as Garth Gilmour has written, “The unknown runner didn’t greatly inspire confidence…. He look awkward, too bulky.” (Foreword, No Bugles, No Drums) Snell quickly put all his trust in Lydiard: “I’d ceased to be a promising tennis player, or a cricketer; I was a track athlete.” (No Bugles, pp. 10-11)

Early Days

Although Snell was an 880 runner, Lydiard focused on building stamina. “Arthur urged me to get out with the boys and move into full distance-training as soon as I could,” Snell recalled. (No Bugles, p. 14) Lydiard gradually developed his new charge until he was ready to tackle the celebrated 22-mile Waiatarua run (“a remote and improbable objective” to the 20-year-old). Snell was in fact training like a marathon runner, trying to build up to 100 miles a week. This approach was totally foreign to conventional 800 training. Snell did of course do some speedwork when the track season came around, but Lydiard believed that Snell’s endurance was the key. As Snell explained many years later, Lydiard’s idea was to develop stamina and higher oxygen uptake so that the track runner did not get into oxygen debt before the final sprint for the tape.

|

| McKnight, Halberg, Snell and Magee on the Waiatarua run. Note Snell's physique. |

Lydiard’s demands were high, but Snell had the strength of character to meet the challenge. Over the first winter he improved his Waiatarua time from 3:00 hours to 2:30 and competed in cross-country. In his first track race of the 1958-59 season, Snell beat Murray Halberg, New Zealand’s top middle-distance runner, over 2,000 in 5:15.8. He then ran 1:51.6 and 4:12.4 to win the Auckland 880 and Mile titles. In the 1959-1960 cross-country season Snell showed a great improvement in his stamina, finishing 4th in the National championships (55th the previous year). But then he suffered a tibia stress fracture that put him out of action for three months. He was struggling to get fit when the 1959-60 track season started. But he was surprised to run 1:49.2 to win the Auckland 880 title. A victory in the Nationals (1:51.3) gave him hope for an Olympic berth.

So he went back to winter training with the possibility of Rome in his mind. In his third week he hit 100 miles for the first time. “But I still wasn’t fully developed under the Lydiard conditioning system,” he wrote later (No Bugles, p. 25) Indeed he was unable to run 100 consistently. But then came the news of his Olympic election, and he celebrated with a PB Waiatura run of 2:12:45. He was now strong enough to put in “a good Waitakete every weekend.” As the Olympics drew near, he had to cope with the New Zealand winter, often doing his speedwork on a measured stretch of road in the dark.

Rome

Snell arrived in Rome as a 1:49.2 880 runner without any international experience. Sports Illustrated called him “completely unknown.” (SI, Sept. 12, 1960) He was lucky to have the companionship of the experienced Murray Halberg, who gave him “a feeling of security.” (No Bugles, p. 31) Before his heats, Snell ran 2:57 for 1320, 1:48 for 800 and 48.0 for 400. These times gave him confidence to make the final. Two heats were scheduled on the first day and then the semis and finals on the next two days. Lydiard thought that four races in three days would be to Snell’s advantage as they had effectively developed his stamina.

In the morning heat he won in 1:48.1, a PB. Then in the afternoon he was second to Moens in 1:48.6. The next day he won his semi in 1:47.2, another PB, this time beating Moens. The finalists lined up on the third day with three hard races behind them in the previous 48 hours. None of the runners was likely to be 100%.

|

| Rome 800: "I suddenly felt I could win." |

Snell ran hard from his outside lane and found a niche in fourth place for the first lap. He was well placed into the back straight, but then five runners moved up outside him. Moens breezed past. At 600, where Snell had planned to sprint, “the field in front of me was three wide…. I had the choice of continuing running on the inside or trying to run right round the field. I chose the easier course. I stayed inside. I felt that this meant abandoning the chance of winning…but there was the hope that the front runners would split and I could get through into a place.” (No Bugles, p. 37)

As the front runners spread out in the straight, Snell did find a gap and moved through. He first thought he had a chance for third, then a chance for second. While all his opponents were hanging on, Snell was charging. With 20 meters to go, he thought for the first time he might win. He flung himself at the tape, not knowing if he had done it. After the race, Moens came over to him. “Who won?” Snell asked him. “You did,” Moens answered. (No Bugles, p. 38)

Thus Snell had run four top-class 800s in three days and had improved his PB three times. This would have been unthinkable without the three winters of Lydiard distance-training. Snell was not the fastest 800 runner in the Olympic final, but he was the strongest.

After Rome

His Rome victory was no flash in the pan. He went on to win two 880s in Europe (1:47.9 and 1:47.5) and to knock almost nine seconds off his mile time with 4:01.5. And then, not surprisingly, there was a low period when he returned home. He had another injury and then performed below par in the 1960-61 New Zealand track season. It was only when he heard that Gary Philpottt had broken his 880 national record that Snell rediscovered his “fire.” He ran 60-70 miles a week for three weeks and then moved up to 100 miles a week. Soon after he got the chance to return to Europe for the summer tour and the 1961 World Games in Finland.

After victories in 1:48.3 and 1:50.4, Snell won the World Games 800 in 1:47.6 from Matuschewski and Salonen. He followed this up with a victory over Paul Schmidt after trailing by 20m. Then it was off to Ireland, where Snell beat George Kerr in a fine 1:46.4 for 800, the fastest time of the year. While in Ireland, the Kiwis tackled the 4xMile WR of 16:25.2. Thanks to anchor leg by Snell of 4:01.2, they broke the WR by 1.6 seconds. Back home, Snell was “extremely exhausted,” but he felt he consolidated his world reputation.

World Records Galore

|

| 3:54.1 WR at Wanganui.Halberg and Tulloh behind. |

Snell returned home to a full-time job as a quantity surveyor. Running to and from work, he was soon up to his 100-miles-a-week regimen. During this building phase for the January 1962 track season, he even tried a marathon, finishing in 2:41. By Christmas he was showing great form. His first serious 880 was a national record of 1:48. In his next race he equaled his Olympic record of 1:46.3 for 800 and clocked 1:47.1 for 880. He looked very good for the Mile in Wanganui: “I knew my form was improving and that I was virtually certain to run under four minutes for the first time in my life.” (No Bugles, p. 90) The field went through in 61 and 2:00. Then Snell had to take the lead. He aimed for 3:00 at the bell and was spot on, but to his surprise Bruce Tulloh, an English distance runner, surged by. Snell held on to him round the bend and then took off: “I found myself running with complete freedom from restraint…. I don’t think I have ever felt such a glorious feeling of strength and speed without strain.” (No Bugles, p. 93) He finished in 3:54.4, a WR by just 0.1 of a second.

Soon after, Snell went for the 880 and 800 WRs. And despite some poor pacemaking that took him too fast through 220 in 26.2 and 440 in 51.0, Snell’s strength enable him to keep going. The 660 was reached in 1:16.9, and he ran 800 in 1:44.3 and 880 in 1:45.1. Two more WRs.

After a quick USA visit, where he ran an indoor WR for 1,000 yards, Snell returned home and ran a 3:56.8 mile. Next he ran an indoor race in Japan before settling down to preparation for his USA race against Jim Beatty. However, when he got to California, it was Dyrol Burleson, fresh from a 3:57.9 relay leg, who challenged him. Snell again triumphed, taking the lead at 200 and winning in 3:56.1 from Burleson (3:57.8) and Jim Grelle (3:58.9).

Commonwealth Games

Then it was back to preparing for the Commonwealth Games in Perth. Soon there was good evidence that Snell was gaining even more stamina. He won the Auckland cross-country title, beating Bill Baillie, and then the New Zealand title. After this encouragement, he began his hill training with great enthusiasm, only to suffer a cracked metatarsal that put him out of action for a month. When he started running again things looked bad for Perth. He started with a 1:56 880 but was soon down to 1:50.9.

He achieved a double in the 1962 Commonwealth Games, winning both the 880 and Mile. George Kerr pushed him in the 880, only ceding the lead 20 yards from the tape. Snell had an easier time in the Mile, protecting his team-mate John Davies round the final bend and then moving past him in the last stretch.

More Successes in the USA

After an anticlimactic New Zealand track season, Snell went to the USA in June, 1963. He ran 4:00.2 in his first race, beating Burleson and O’Hara. But it was Jim Beatty who was thought to be the best challenger to Snell. When he finally met the American, he showed how tactically adept he was. After coasting through 800 in 1:59 and to the bell in 3:02 (in fourth place behind Beatty, Grelle and Weisiger), Snell found a way to keep Beatty under control: “Going into the bottom bend, I saw a chance to box Beatty and prevent his famed 300 kick. I ran wide to his shoulder and hung there.” (No Bugles, p.146) Beatty was held in check until the last bend, when Snell sprinted. “Never before have I sprinted like this in a race,” he wrote. (No Bugles, p. 147) Going into the straight he was up 10 yards and then increased his lead even more, winning in 3:54.7 from Weisiger (3:57.3), Beatty (3:58) and Grelle (3:58). In the last USA Mile race in Compton, Beatty was closer, but Snell still won (3:55 to 3:55.5).

Tokyo Build-Up

Newly married, Snell found training difficult for the next few months, and when he ran a Mile in October, he could manage only 4:12. But by January 1964 he was showing much better fitness with a solo 3:57.6 Mile. However, he posted no other good times in the New Zealand track season, and the local press were saying he was past it.

After a March vacation in South Africa, with a few non-pressure races, Snell began to prepare in earnest for the Tokyo Olympics in August. “Stamina was again going to be the key. I began running twice a day…aiming to reach 100 miles a week as soon as possible. I made it after two weeks…. I could never run more than three consecutive weeks of 100 miles, but over 10 weeks I logged a total of 1012 miles—the greatest amount of distance running I’ve done.” (No Bugles, p. 168-9) During this build-up period he did no speed work at all; everything was slower than 6-minute miles.

Then 15 weeks before the Olympics, Snell moved into six weeks of hill work. This went “exceptionally well.” His first track session was 20x440. Hoping to average 65, he managed 62.5. Snell worked on his track speed with “a great deal of short, sharp sprint work.” (No Bugles, p. 170) His confidence was such that he didn’t feel the need to run any fast race times before the Games.

Double Gold

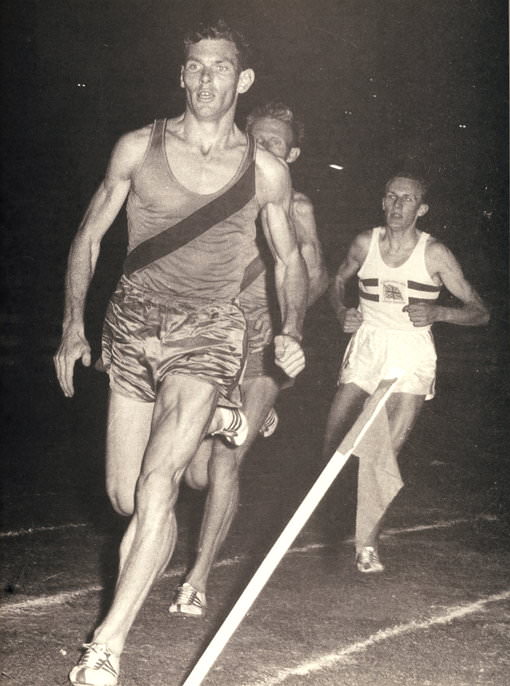

|

| Total domination in Tokyo. Snell wins the 1,500. |

On arriving in Tokyo he caught the flu. When he started running, his team-mate John Davies was in far better shape. Time trials over 1320 (2:56) and a Mile (4:02) were almost at his limit. But an 800 time trial in 1:47.1 a week before the 800 heats left him “overjoyed.” After winning his heat and semi, Snell planned to start fast in the 800 final, expecting Kiprugut to make a fast pace as well. But this didn’t happen, and he found himself boxed in near the front. At the bell several runners roared past and Snell, still boxed in, was unable to react. He had to drop back to escape the box and then surge up into about fourth. Then at 200 he surged past Kerr and Kiprugut. He held the lead into the straight and hung on for a clear victory in 1:45.1. Crothers of Canada was the closest to him, half a second behind. Later, Snell wrote,“I felt I was giving it everything I had down the straight, although there was no sign of weakening but, on reflection, I think that in spite of the desperation of that last half-lap, I subconsciously held just a little back for the 1,500.” (No Bugles, p.184)

Snell’s stamina was needed in the 1,500, for a fast heat left a lot of the finalists tired. He ran a fast 3:38.8 to qualify. In the final, a slow second lap after a brisk 58 opener led to a lot of jostling, and again Snell got boxed in at the bell. This time he managed to move out and position himself for his final effort. Feeling rather tired, he delayed this final effort until 200 to go. His amazing speed left all his opponents well behind. Running the last 400 in 53.2 and the last 300 in 38.6, he was in a class of his own. The photo of him finishing shows how dominant he was. Snell had won two golds in style.

Career Wind-Down

The New Zealand track season began three months later. Not surprisingly Snell was still fatigued from his Olympic efforts and was only doing “spasmodic training.” But he felt an obligation to race. He came up trumps again, beating the 1,000 WR and the Mile WR with 2:16.7 and 3:54.1. In December 1964, a tired Snell went to Australia and managed a 3:57.6 Mile to beat the Australian record.

A final world tour was on the cards for 1965. He trained hard from January to the end of May. On June 4 in the USA, he won a Mile race in 3:56.8 against Odlozil, Grelle and Ryun: “ I’d never been made to run that hard up the straight,” he wrote later (209) This was the last international race that he won. He was beaten over 880 in Canada by Bill Crothers, and then by Jim Ryun in California. In Finland he was 5th in a 1,500, and in Dublin he was beaten by Whetton and Wiggs over a Mile. Odlozil beat him in Prague and Crothers (again) in Oslo. In his last race, a mile in Berlin, he was third behind Grelle and a local runner.

Back in New Zealand, Snell announced his retirement. It had been an amazing career. From the 1960 Rome Olympics to the 1964 Tokyo Olympics he was unbeatable over 800 and 1,500. He was, through his Lydiard-style training, a new type of 800/1,500 runner who could win his national cross-country title and run a 2:41 marathon.

Note: For this article I have relied heavily on No Bugles, No Drums by Peter Snell and Garth Gilmour. Though out of print, it is still available second hand. I recommend it as one of the best runner autobiographies.

9 Comments