Book Review: Three Books on Emil Zatopek

Frantisek Kozik. Zatopek the Marathon Victor. A Reportage on the World’s Greatest Long-Distance Runner. Prague: Artia, 1954. 215pp.

Frantisek Kozik was a Czech writer with strong literary credentials. He was already established as a biographer when he wrote Zatopek the Marathon Victor. It covers Zatopek’s career up to 1954 in detail and manages to get to the essence of this great runner. Kozik uses his dramatic experience as a writer of radio plays to build up the excitement of Zatopek’s many great races. Here is the end of the London Olympic 5,000, where Zatopek is trying to catch Belgian Reiff: “[Reiff] tried once more to increase his speed, but his will was not as strong as Zatopek’s. He had used up all his reserves, his body was exhausted, his stride was unsteady. He glanced around once more, and the distance had diminished. Emil had achieved a terrifying self-conquest, and his body, which no longer felt the terrible pain, was at this moment driven forward by willpower. Reiff could see the tape. A victory for his country, for Belgium, was within his reach…but behind him the swift spanking step of his irresistible opponent. He could hear Zatopek’s breathing getting nearer.” A little over the top, yes. There was no way he could have heard Zatopek’s breathing above the roar of 60,000 spectators. But Kozik manages to draw the reader into the drama of the great Czech’s major races.

|

Kozik’s main contribution is the mass of information he provides. He was able to talk to Zatopek extensively and to provide full details of all the important races. This material has been invaluable to those who later wrote about Zatopek. As Bob Phillips says, Kozik’s biography is “the primary source of information regarding Zatopek’s formative years and the greater part of his international competitive career.” (14-15)

One of Kozik’s main techniques is to include anecdotes for dramatic effect. For example, he has an unfriendly and embarrassed flag bearer lead Zatopek as the sole Czech participant in a military games. Then when Zatopek wins, the flagbearer instantly becomes his biggest fan. Many of the anecdotes, as well as the dialogue used in them, may well be apocryphal, but they dramatise effectively.

What does jar the reader today is the political bias. Kozik’s 1954 book clearly had to promote the political propaganda of the occupying Soviets. As Bob Phillips has written, “Many of Kozik’s observations…smack too much of guileless propaganda.” (15) Thus the Russians who invaded Czechoslovakia in 1945 are called “the brave liberators”: “But the brave liberators did not falter a single step…. They held the enemy in check with all the weapons at their disposal, yet those barely rested troops even went over into attack. In a short while the enemy was wiped out.” Throughout, Kozik portrays Zatopek as the ideal citizen: “Emil is not only a good sportsman but also an exemplary worker. In spite of his time-consuming training, he conscientiously manages to fulfill all the duties imposed on him as an officer. It is not therefore surprising that such an exemplary young man, apart from his racing activities, should take part in many public events.” (88)

Overall, Kozik’s richly illustrated book is a good read. True, it is full of hyperbole and political propaganda, but it nevertheless provides a good understanding of the amazing Czech runner. The only problem is that the book is very hard to find—and expensive. I found one copy on Amazon.co.uk for $175.

Recommended.

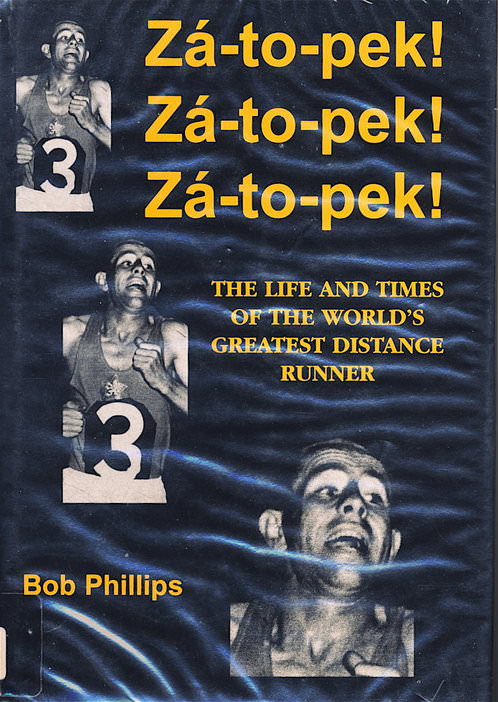

Bob Phillips. Zatopek! Zatopek! Zatopek! The Life and Times of the World’s Greatest Distance Runner. The Parrs Wood Press, 2002. 139pp.

|

A respected author in track and field and a veteran BBC radio commentator, Bob Phillips has all the credentials to write the definitive biography of Zatopek. And he has done just that. This book is without a doubt the most valuable account of the great Czech’s career. Sadly, Phillips was unable to write the book before the great man died in 2000. Had he been able to get to the project earlier, Phillips would have been able to talk to Zatopek in depth, and thus not have to rely so much on secondary sources. Nevertheless, Phillips does a fine job collating all the available material—Kozik’s biography, J. Armour Milne’s reports to Athletics Weekly, Peter Lovesey’s The Kings of Distance, to name the main sources. The result is an informed commentary on Zatopek’s achievements on the track.

Everything is there. Phillips’ book provides all the stats. He gives the full results of all the major races he describes. And at the end there are seven pages, compiled by Milan Skocovsky and Stanislav Hrncir, covering all Zatopek’s’s races: his PB progress, results from championships, year-by-year rankings and all races categorized under various distances.

What I found most valuable in this book is the contextualizing. Phillips uses his considerable knowledge of the sport to put Zatopek’s achievements in perspective. In the introduction he shows how amazing it was that a great runner should emerge from “such an obscure corner of Central Europe [Bohemia]” where there was no tradition at all in world-class running. Discussing Zatopek’s 10,000 WR in 1950 (29:02.6), Phillips points out that only five men the previous year had run a 5,000 time as fast as Zatopek covered the first half of this race. In discussing the eventual eclipse of Zatopek’s WRs by Kuts and Iharos, he points out that Kuts negated the widely held belief that runners like Iharos were breaking records because they had better miling speed. Kuts’ best 1,500 PB was almost exactly the same as Zatopek’s: “a dedicated system like that of the USSR with such a large and diverse population...was likely to find sooner or later someone strong enough who could train as hard [as Zatopek], or harder.” (105)

Phillips’ book effectively evokes Zatopek’s individuality. His races descriptions, with pertinent information on Zatopek’s opponents, are great reading. Highly recommended but hard to find, even on the Internet.

Highly recommended.

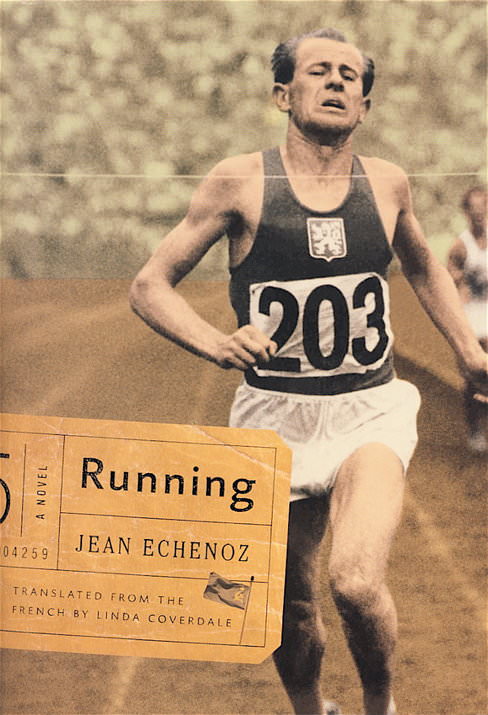

Jean Echenoz. Running. A Novel. Translated by Linda Coverdale. 2009 126 pp.

This brief novel, a novella really, narrates the story of Emil Zatopek in a political context. In fact, the political material comprises approximately half the novel. Though interesting and informative, this material is probably not what readers of this website are looking for. So what of the “running” content?

|

Well, Running: A Novel is a huge disappointment. Echenoz is a highly regarded French novelist and winner of many prizes including the prestigious Prix Goncourt. He is admired for his style. Indeed, this book has been called “magnifique” and a “beautifully imagined and executed portrait.” But Echenoz’s research on running has gone barely beyond Kozik’s biography, which he uses extensively without any attribution. Many of Kozik’s anecdotes, some of which are likely apocryphal, are lifted straight from Kozik. For example, he uses Kozik’s idea that Zatopek was originally an unwilling runner—and exaggerates it. From inheriting an “antipathy to exercise” from his father, he then “likes running now and finally “soon starts enjoying himself.” (pp. 14,17,18) Along the same lines, he copies much of Kozik’s description of Zatopek’s now legendary “holding breath” experiment, where Zatopek runs along a line of spruce trees, each time holding his breath for one more tree until in his final attempt he passes out on reaching the last tree. There are many other examples.

It is clear that Echenoz knows little about running and has not even gone to the trouble of getting his manuscript properly checked. He says that Emil “invented” the final sprint in a race. He wrongly says that Zatopek entered the final straight of the 1952 5,000 final in third place. He writes that while Z was in Delhi he ran “seventy kilometers every day.” (p. 102) That’s 490K a week. Wow!

Echenoz, perhaps influenced by Kozik, is prone to hyperbole and cliché. Early on Zatopek runs against “tall, lean arrogant” Germans, “Aryans,” whereas the Czechs are “raggedy, haggard peasants in long undershirts or weekend soccer players in need of a shave.” (p. 17) When Zatopek heads into the final stretch of one race, “the public is on the verge of fainting.” (42) And Zatopek arrives in the Helsinki stadium to win the Olympic Marathon “as fresh as a daisy.” (p. 75)

Perhaps the most risible writing is Echenoz’s description of Zatopek’s running style. “There are runners who seem to fly, others who seem to dance, others who look as if they were parading, and some appear to be advancing as though they were sitting on top of their legs. Emil, you’d think he was excavating, like a ditch digger, or digging deep into himself, as if he were in a trance.” And later: “It’s as if he had a scorpion in each shoe, catapulting him on.”

Echenoz is respected in France for his writing style. But Linda Coverdale’s translation gives no evidence of a great writer at work.

Not recommended.

Leave a Comment