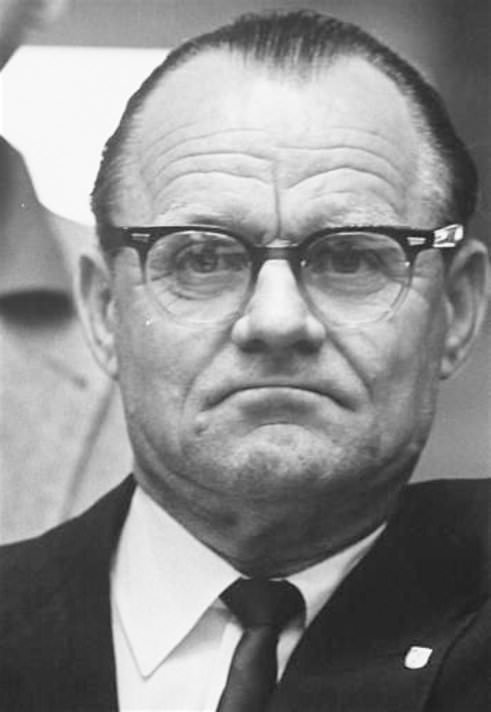

1913-1995 Austrian-born Franz Stampfl was one of the leading coaches of the 1950s and 1960s. He developed his own interval-training system from Gerschler’s pioneering work. Stampfl’s system was used effectively by Chris Chataway and Chris Brasher in England, and later by Merv Lincoln and Ralph Doubell in Australia. Stampfl was an intellectual. Coaching for him was not merely training the body. He put equal emphasis on the mind, not only with psychological development but also intellectual development. Chris Chataway said, “When I first met him I realized he had a remarkable understanding of human nature and a devastatingly infectious enthusiasm.” (O’Connor, Sports Illustrated, Nov. 26, 1956) According to Brian Hewson, Stampfl “not only made sure his athletes were physically fit, he made sure they were mentally fit as well.” (Flying Feet, p.61) This is where he differed from most coaches. If coaching can be defined as a blend of art and science, Stampfl put much more emphasis on the art than most coaches. This involved spending long hours in conversation with his main athletes. “We would go down to lunch on Lygon Street,” Ralph Doubell recalled. “We’d be first there at lunch, be last to leave. Then we’d go from there to Jimmy Watson’s wine bar. So between 12 and 4 I had an earful of Stampfl, but by the end of it I could normally believe that I could beat anybody in the world.” (Amanda Smith, The Sports Factor, Jan. 2001)

GORDON PIRIE PROFILE1931-1991 Gordon Pirie’s serious running career began when, as a 17-year-old, he witnessed Zatopek’s 1948 Olympic performances: “My imagination was set on fire and my consuming ambition was born. I instantly recognized him as the embodiment of an ideal for myself as he scorched through the 10,000 field. From that day he has never ceased to be my greatest inspiration and challenge and my firm friend.” (Pirie, Running Wild, p.16) Not endowed with great natural ability, Pirie achieved success through following Zatopek’s example: “He burst through a mental and physical barrier. He showed runners that what they had been content with up to then was nothing to what could be achieved.” (RW, p.16)

Profile: Herb Elliott b. 1938 The bare facts of Herb Elliott’s career say it all: unbeaten over One Mile and 1,500; Olympic 1,500 champion in WR time; and Empire Games double champion. He was one of the greatest runners of the twentieth century.Something of the unique character of this man can be shown in my sole encounter with him. He had committed to run an 880 in my home town of Brighton. However, he was completely out of shape, not having run for weeks. Nevertheless, he still turned up and ran his guts out—literally. He was violently sick afterwards. His time was a mundane 1:55, but he had honored his commitment and given his best. Once he had recovered I approached him for an autograph in his book The Golden Mile. He signed it with pencil, and in response to my comment that I had enjoyed the book, claimed that he hadn’t read it. Modesty, perhaps false modesty, but still modesty.

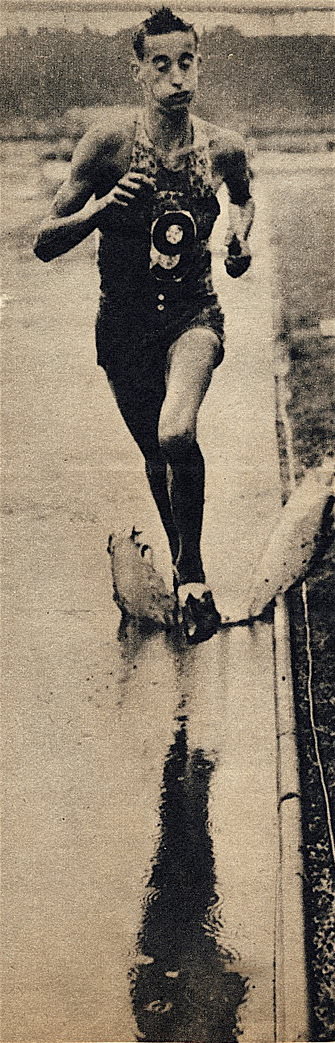

HORACE ASHENFELTER: PROFILE b. 1923 5’10”/1.78m 128lbs/58kg Horace Ashenfelter’s 1952 Olympic win in the 3,000 Steeplechase is widely regarded as one of the biggest upsets in Olympic track. To start with, he was not a steeplechaser. So he was competing as a novice in what is the most technical running event. His steeplechasing experience was limited to just six races (some say eight). Over the previous winter he had been practicing hurdling, but this was limited to working on a single hurdle that he built himself. Then he was up against two highly experienced and technically trained Russians, Vladimir Kazantsev and Mikhail Saltykov, the first two to break the 1944 world record of 8:59.6 with 8:49.8 and 8:57.6 respectively. Ashenfelter came to the Olympics with a best of 9:06.4, a full 17.8 seconds slower than Kazantsev’s new 1952 world record of 8:48.6.

IHAROS, ROZSAVOLGYI, TABORI:PROFILE: THE HUNGARIAN TRIO In 1955, the year before the Melbourne Olympics, Hungarian runners shocked the world with a slate of nine world records from 1,500 to 5,000. It was one of the greatest record explosions ever in track running. This breakthrough came from three runners: Sandor Iharos, Laszlo Tabori, and Istvan Rozsavolgyi. A crucial reason for this explosion was the coaching of Mihaly Igloi (see Profile). Igloi had become coach of the Army team Budapest Honved in 1951; he took over as Hungarian National Coach in 1953.

Jim Peters was one of the greatest marathon runners. His domination in marathon running in the early 1950s is often overlooked because his dramatic collapse near the end of the 1954 Empire Games marathon in Vancouver is so well documented. From his first marathon in 1951, Peters was breaking records. In this marathon, his 2:29: 24 clocking made him the first British runner under 2:30. In the next three years he gradually improved his times. With his Poly Marathon win in 1954, he ran a World Best for the fourth time with 2:17:39.4, his career best. During this progression from 2:29 to 2:17 he was he first man under 2:25 and the first under 2:20. The previous World Best was 2:25:39 by Korean Yun Bok Suh (disputed for being on a short course); Peters improved that by 8:00 over his career. No one before or since has lowered the World Best marathon time by so much.

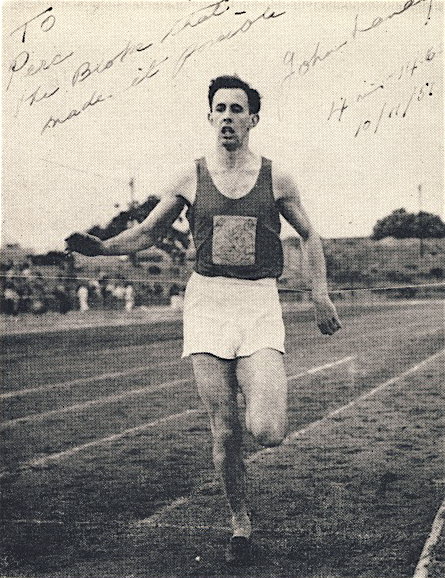

The second man to break the four-minute-mile barrier, Australian John Landy is universally respected as one of the great runners of the twentieth century. His dignity, sportsmanship and courage are beyond dispute. However, he will always be seen as the one who could have—could have run the first four-minute mile and could have won Olympic and Empire titles.Born into a prosperous family in 1930, Landy went to the prestigious Geelong Grammar School and then studied agriculture at Melbourne University. Like most Australians, he was sports-minded, originally trying to succeed in Australian–rules football. He also ran to keep fit for football. When he made the state athletics team in 1951, he decided to take the sport more seriously. After winning the Combined Schools Mile in a modest 4:43, he was introduced to Percy Cerutty, the colourful local coach. This meeting changed Landy’s life; he gave up football and started to train seriously as a runner.

Profile: Max Truex1935-1991 Max Truex was the precursor of the successful modern American tradition in distance track running. His sixth place in the 1960 Olympic 10,000 opened the door for American distance runners in the next Olympics, where they surprised the world by winning golds in both the 5,000 and 10,000 and also a bronze in the 5,000. Before 1960 American distance runners had rarely been competitive on the international scene. Charlie Capozzoli, who won a major European Three Miles in 1952, and Curt Stone, who was sixth in the 1952 Olympic 5,000, were two exceptions. But it was Truex who made the real breakthrough when he became the first American since 1912 to place in the top six of the Olympic 10,000.

This celebrated Hungarian coach started his track career as a pole vaulter before becoming a successful 1500 runner. He had several Hungarian titles to his name and competed in the 1936 Olympic 1,500. Furthermore, he was a member of the Hungarian team that set a 4x1,500 WR of 15:54 in 1939. His motivation to change from pole vaulting to track running came from watching Polish 10,000 OG champion Kusocincki, who, according to Frank Litsky would run 200 repetitions in training. (This training method precedes Gerschler’s interval-training innovations as Kusocincki must have been doing this in 1932 or before.) During his running career, Igloi spent time in Germany, Finland and Sweden learning about training methods.

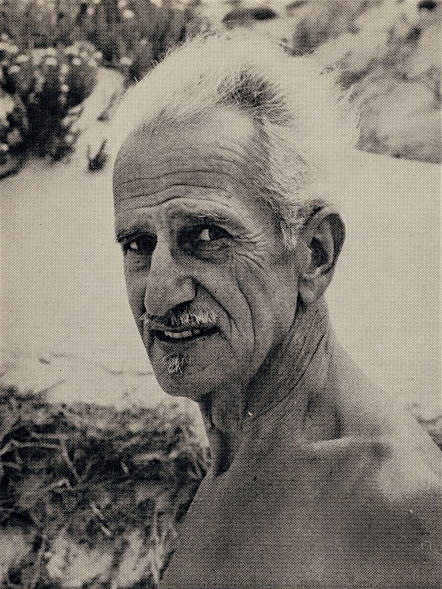

To call Percy Cerutty passionate would be an understatement. To call Percy Cerutty eccentric would also be an understatement. To call Percy Cerutty a deep thinker would be accurate. To call Percy Cerutty an inspirational coach would be accurate too, although he was too extreme for many athletes. Cerutty’s eccentricities, which were fuelled by his unbounded enthusiasm, often got him into trouble. His run-ins with authorities led to his being passed over for a coaching job at Melbourne University that opened up just before the 1956 Olympics. Cerutty was already the most successful coach in the Melbourne area when Franz Stampfl was brought in from England. “I was the local boy,” he wrote later. It was understandable that Cerutty was sorely miffed, but he would never have settled into the discipline of a university position. Indeed, he claimed that he would have refused the job: “Nothing could have appealed to me less that having to organize classes and lectures.” (Cerutty, Sport Is My Life, 53)